Dick Button with his favorite trophy, given to him in 1947 by Ulrich Salchow (1877–1949), perhaps the greatest male skater of the early Twentieth Century. It is not in the Cooperstown show.

By Laura Beach

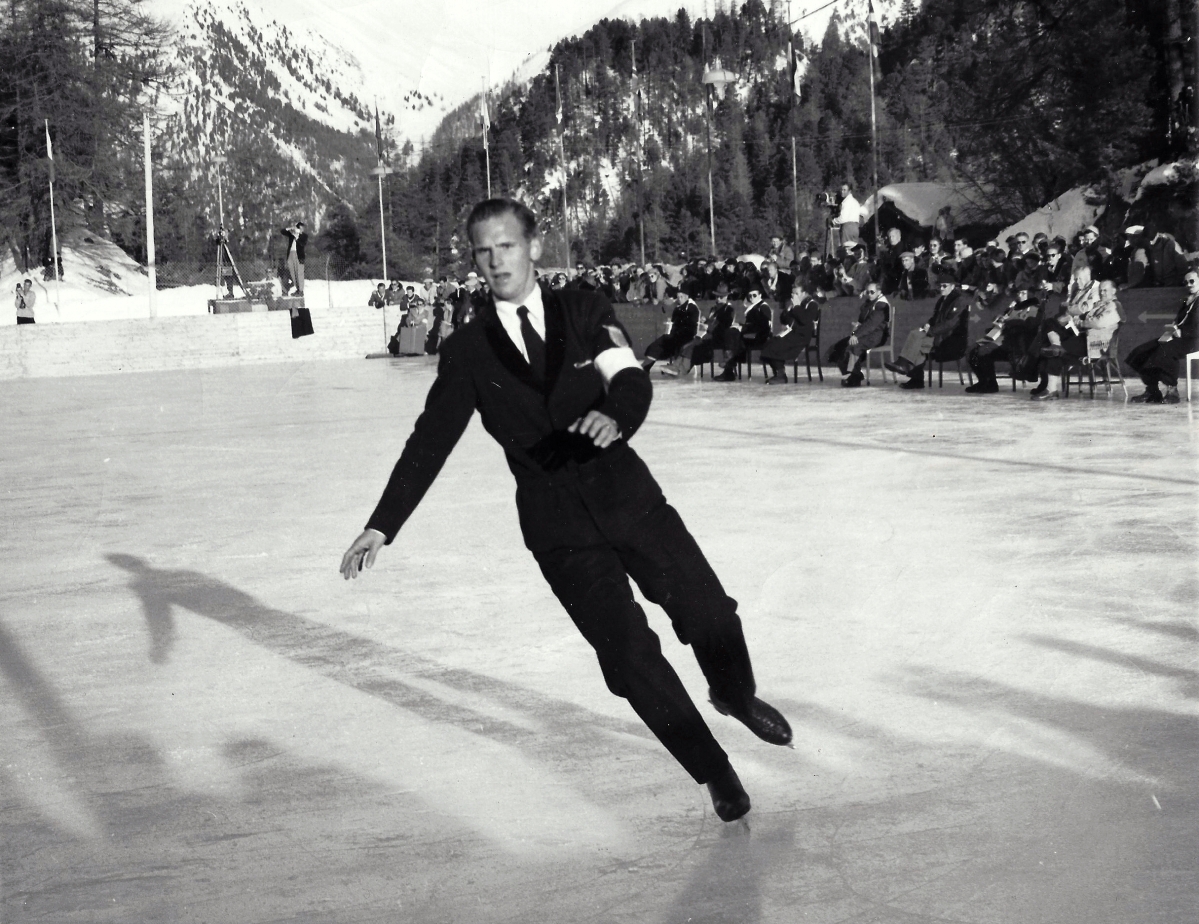

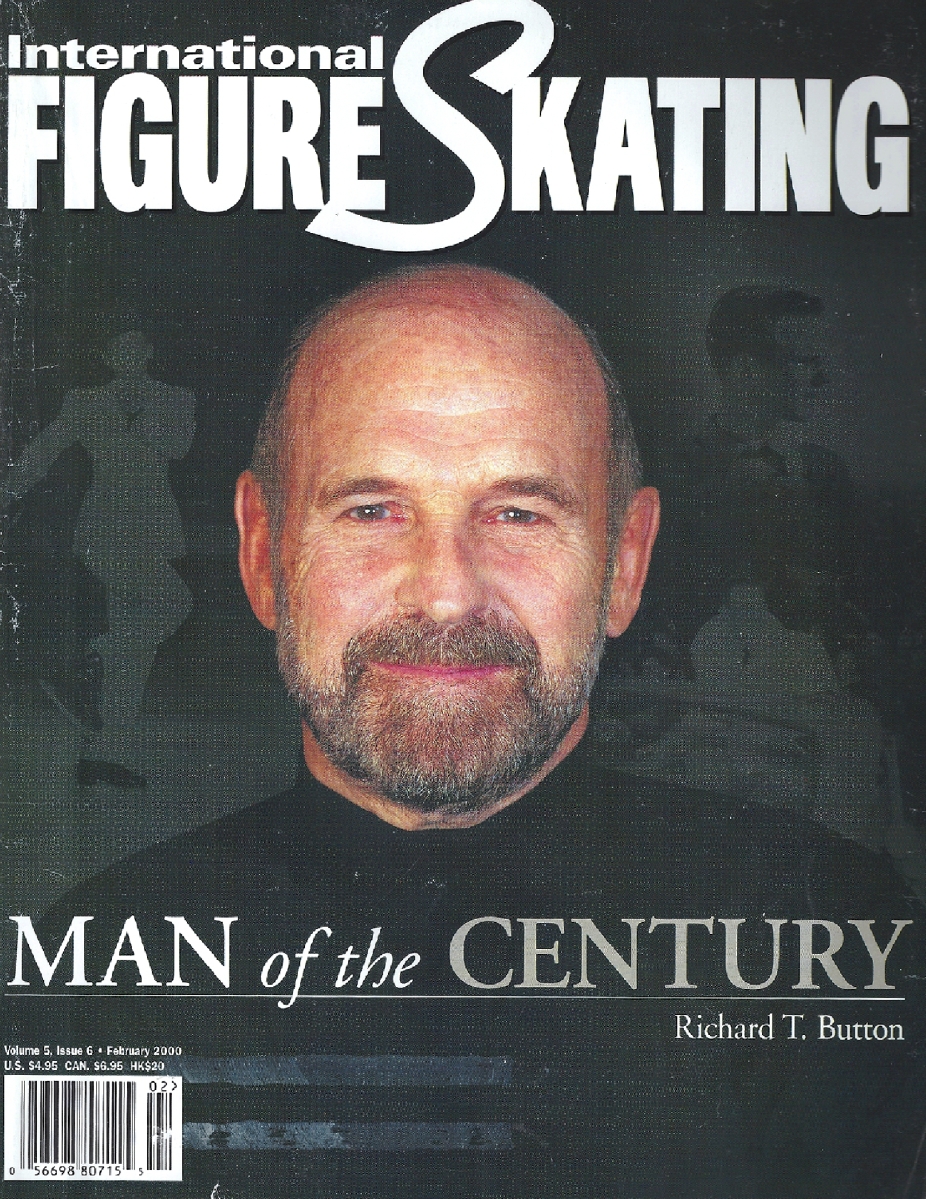

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. – Dick Button is a man of many firsts. The two-time Olympic gold medal winner in figure skating was the first to land a double axel, the first to land a triple jump, the first and only male skater to hold simultaneously the National, North American, European, Olympic and World championships. He won the World Championship five times. The Button Camel is named for him.

Here are some things you may not know about Dick Button. He turned down Yale to attend Harvard, participated in Hasty Pudding theatricals while skating competitively, gave up his amateur skating status to go pro while enrolled at Harvard Law School, passed the D.C. bar, but left law for a career as a skater, actor, director, producer and commentator.

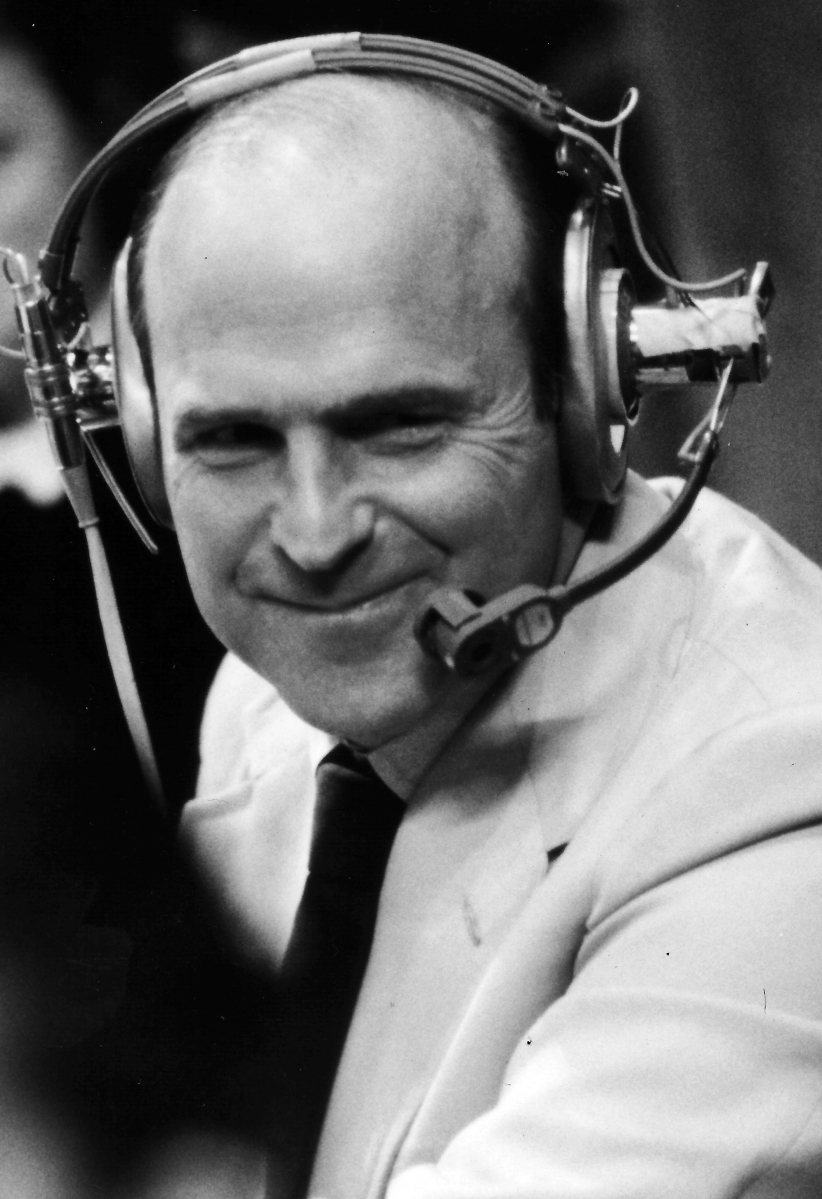

In 1981, Button, a member of the Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame, became the first individual to win an Emmy Award for Outstanding Sports Personality-Analyst. Writing in The New York Times in 1968 about the Grenoble Winter Games, Jack Gould proposed a medal for Button’s color commentary, notable for its candor and critical objectivity. “The former skating virtuoso has been head and shoulders above the entire ABC journalistic corps,” penned Gould.

“Dick is a very interesting man, well-versed in such a variety of things. He lives a full life. We were together for 28 years at ABC and traveled the world,” says skater Peggy Fleming, who has known Button since she was 15.

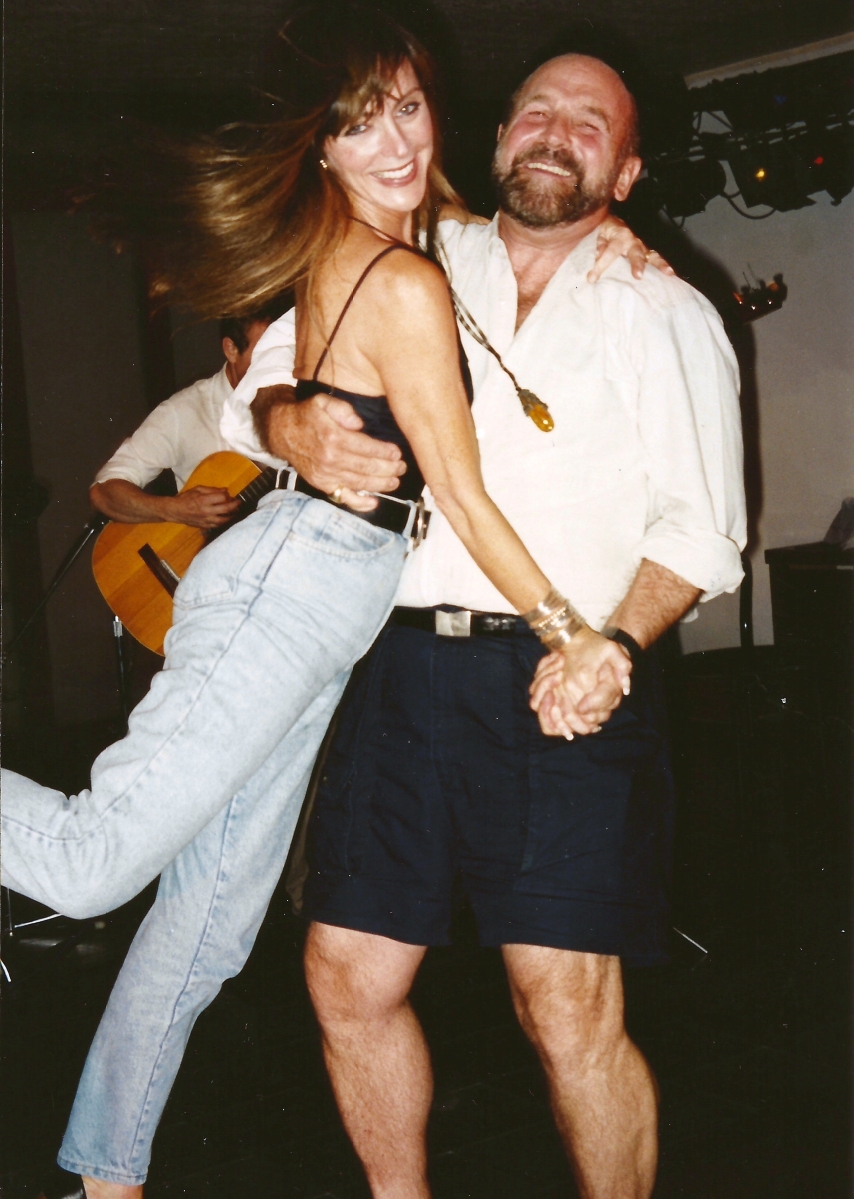

Fleming’s fellow Olympian JoJo Starbuck adds, “Over the years, I’ve been delighted to spend time with Dick. He is always thinking at such a fast pace. His mind is always on the cutting edge of things in art, skating, architecture, gardening, parenting and the politics of these things. I adore being in his company because he is so bright, witty and mischievous.”

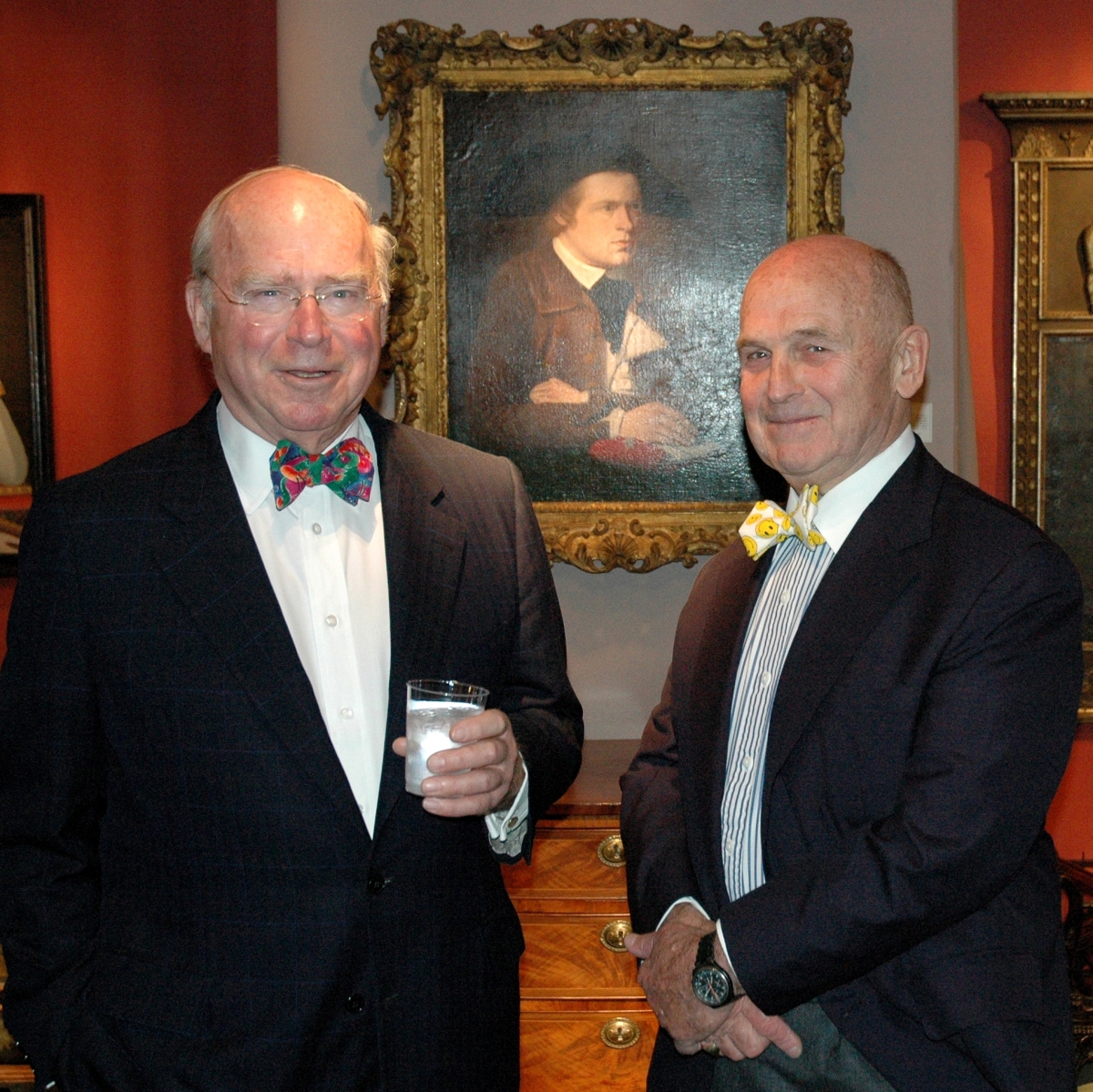

Button belonged to the “Empire Mafia,” the circle of enthusiasts that formed around Berry B. Tracy, a pioneering scholar of Nineteenth Century American decorative arts. He is a serious collector of Classical American furniture, Nineteenth Century American paintings and skating art and artifacts. A consummate gardener whose Ice Pond Farm in Westchester County, N.Y., is a favorite stop for design enthusiasts and horticulturists, he is a fundraiser for just and noble causes, man about town, father of two, friend to many. As an aside, Button appeared in the 1978 film The Good News Bears Go to Japan. He played himself, a sports commentator critiquing a sumo-wrestling match, which should tell you something about his divinely wicked sense of humor.

Button belonged to the “Empire Mafia,” the circle of enthusiasts that formed around Berry B. Tracy, a pioneering scholar of Nineteenth Century American decorative arts. He is a serious collector of Classical American furniture, Nineteenth Century American paintings and skating art and artifacts. A consummate gardener whose Ice Pond Farm in Westchester County, N.Y., is a favorite stop for design enthusiasts and horticulturists, he is a fundraiser for just and noble causes, man about town, father of two, friend to many. As an aside, Button appeared in the 1978 film The Good News Bears Go to Japan. He played himself, a sports commentator critiquing a sumo-wrestling match, which should tell you something about his divinely wicked sense of humor.

Button’s latest title is guest curator. Drawing on his unparalleled insight into the art of skating, both as it is practiced on ice and as represented in two- and three-dimensional form, he has assembled “The Art of Figure Skating through the Ages: The Dick Button Collection.” The Fenimore Art Museum display runs from April 1 through 2017 and features paintings, prints, sculpture, photography, posters, antique skates and costumes from the Seventeenth Century to the present. The project arose after a friend who owns a house near Cooperstown and is a fellow member of the Skating Club of New York introduced Button to Fenimore Art Museum President Paul D’Ambrosio.

Dick Button was still marveling at the New England Patriots’ unprecedented come-from-behind win at the Super Bowl when we got together in February. He observed in the Patriots’ victory something he sees in every champion: focus and unyielding determination. Of his own gold-medal triumphs in St Moritz and Oslo, he says, “I did the best I could for the 1948 games. As for the 1952 games, I was a better skater but over trained and made mistakes. It still irks me.” For more, he refers the listener to his books. Two of them – Dick Button on Skates, first published in 1955, and Push Dick’s Button, which came out in 2013 – offer an unusual combination of biography, critical commentary and instruction from a man whose success in so many undertakings stems from his comprehensive understanding of performance.

“It’s not so much what we’ve taught each other. It’s what we share. We have that show biz thing. I began dancing at 9, about the age Dick started skating. It’s all very theatrical,” says the producer, director and choreographer Dennis Grimaldi. Currently at work on the films Cry Havoc and Frisco Disco, Button’s friend of 33 years admits, “Dick did teach me to look at choreography for skating differently. In dance, it takes five steps to get across the stage. In skating, it takes one.”

Few sports have been more artfully depicted than ice skating. The reasons are obvious, at least to Dick Button. “For me, free skating constitutes the essence of the sport… Music, originality and athletic prowess are combined. It is by far the most exciting and interesting part of the sport for audiences as well as for many skaters,” he wrote in Dick Button on Skates.

“What about skating entertains you? Moves you? It’s a performance sport. It includes costume, choreography, music, design, concept, humor, history. Why is one artist Picasso and another forgotten? Every great skater is creative and individual,” Button tells me, summoning the memory of Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean’s gold medal-winning performance to Ravel’s Bolero at the 1984 Olympic Winter Games.

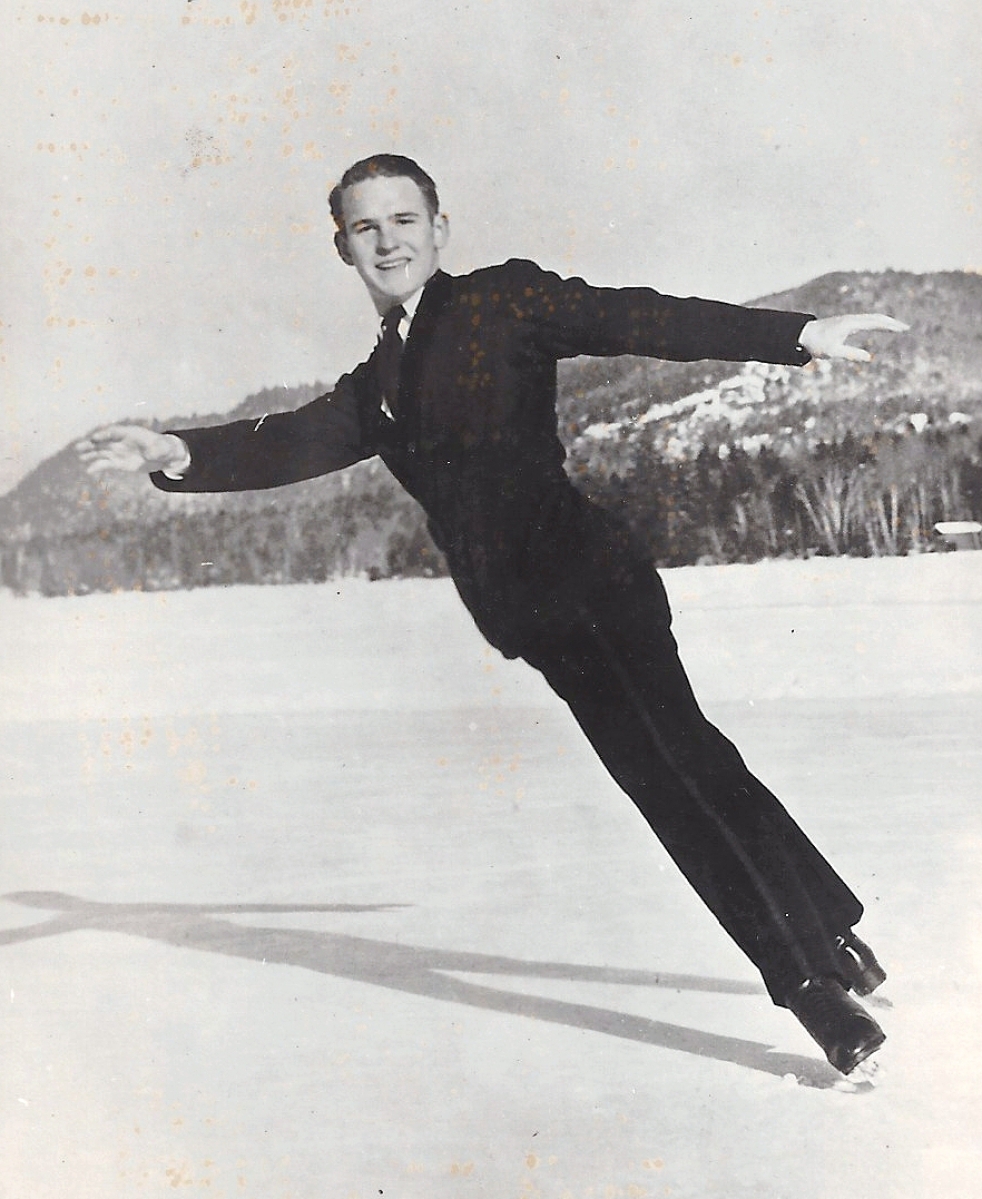

Richard Totten Button grew up in Englewood, N.J., the youngest of three sons of a business executive and his wife, a descendant of an old Staten Island, N.Y., family who encouraged his interest in history. At camp one summer in New Hampshire, Dick’s brothers earned the nicknames Big Butt and Little Butt. The fleet of foot Dick was called Zipper, a moniker it took years to shed. His earliest recollections of skating on Crystal Lake, where he was first taken by his brothers, remain vivid. “I do not know how it could have captivated me even before I was to feel the thrill of almost flying, of scarring up clear, black ice while a gusty wind forced me onto a strong lean and a sharp edge. But as the saying goes, ‘I had it’ as far back as my memory extends,” the Olympian wrote in Dick Button on Skates.

His initial pair of skates cost $17. The disdain of his first instructor, who predicted Button would never be a skater, “not even if a snowball could live in Hades” – prompted Button’s proud father to arrange lessons in New York City for his son with English ice dancer Joe Carroll. “He was a ladies’ man, through and through; wore spats, a vest and kid gloves, and taught the ladies how to dance on ice while simultaneously dazzling them,” Button writes. Carroll referred the Buttons to the famous skating program in Lake Placid, N.Y., home of the 1932 Olympic Winter Games. There the 13-year-old athlete met the coach who changed his life, Gustave Lussi (1898-1993).

“Everything I know about the technique of skating I learned from him, and under his tutelage I won every title there was to win save two for a period of ten years,” Button recalls. The former ski jumper “was a teacher who not only taught by precise examples of every position but who also intrigued us with his enthusiastic embrace of many other skating elements, as well as other subjects.”

Button began collecting skating art and artifacts around the time he started competing internationally. Fans offered American skaters souvenirs nearly everywhere they traveled, something their “already overloaded trunks could not stand,” he writes. Cecilie Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1898-1995) offered Button the fine collection she assembled with her husband, Gillis Grafström (1893-1938), the Swedish figure skater who won three consecutive gold medals in the 1920s. Button’s father agreed to underwrite the acquisition, but the skater, 17 at the time, passed. “What was I going to do with all those dusty old things?,” he recalls thinking. Madame Grafström nevertheless insisted he take a Seventeenth Century Dutch delft tile as a keepsake. On view in Cooperstown, the cornerstone object is one of 30 Dutch tiles decorated with skaters or skating scenes Button now owns. Grafström’s collection ended up at the World Figure Skating Museum in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Button with an early Nineteenth Century skate sign made of wood, metal and leather. He also collects American Classical furniture and Nineteenth Century American paintings.

Button soon made up for his youthful hesitation. “I’ve bought everything I could find. Every time I traveled in Europe I made a point of visiting shops. I brought back wonderful travel posters. Dealers would say they had nothing on skating. I’d say, ‘how about winter?’ Out would come something with skating. I bought ‘Skating before the St. George’s Gate in Antwerp’ that way,” the collector remarks of a mid-Seventeenth Century print after Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Button was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art with other members of the William Cullen Bryant Fellows, a group of scholars and collectors dedicated to the study of the American arts, when they came upon what may be the greatest skating painting of all time, on loan from Washington’s National Gallery of Art. Gilbert Stuart’s larger-than-life portrait of 1782 depicts William Grant – hat cocked, arms crossed and skating on the Serpentine River in London’s Hyde Park. “I asked if anyone knew what the very small skaters in middle distance of the painting were doing,” recalls Button, who informed his colleagues that the men were offering a “Serpentine Greeting,” a formal courtesy delivered on skates that is elsewhere called the “Philadelphia Greeting” or “Pennsylvania Greeting.” “This identification was my one and only contribution to art history,” Button jokes.

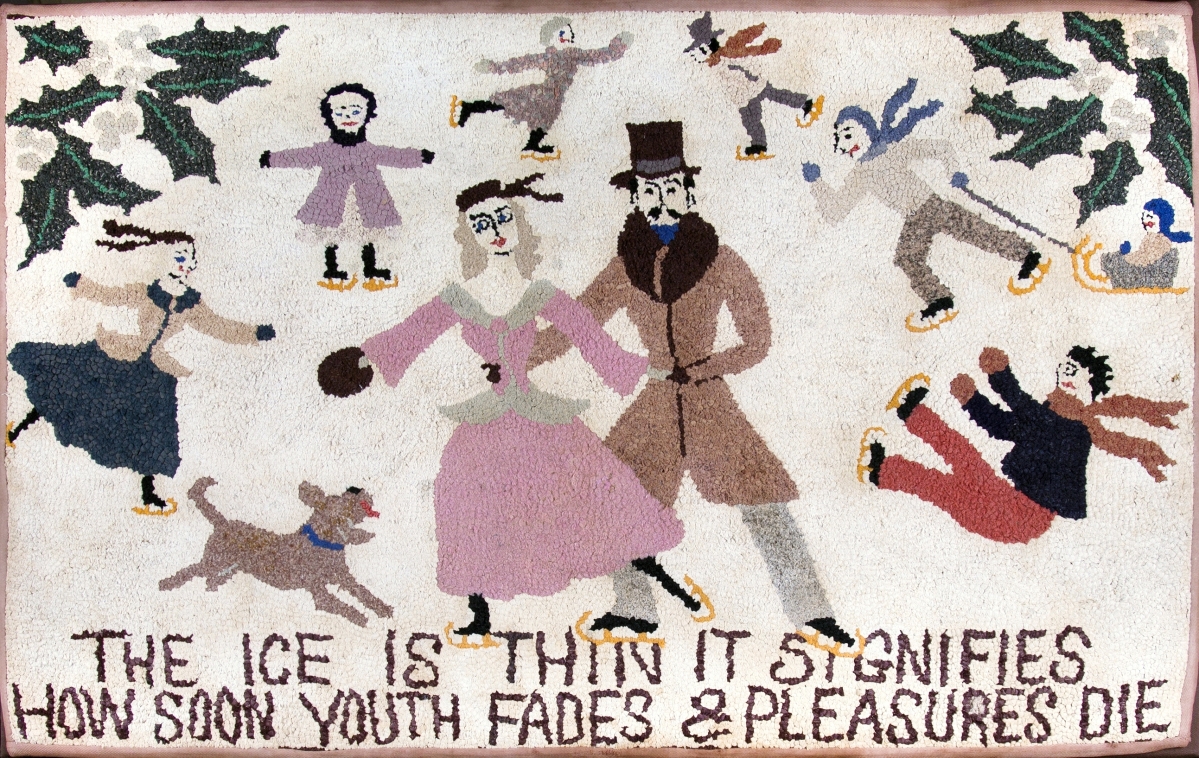

Humans discovered the transportational uses of ice well before the Tenth Century, about the time popular references to skating entered Scandinavian poetry and mythology, as well the approximate date of a primitive bone skate Button found in an antiques shop in Sweden. The dealer told him the single skate was used much like a skateboard, something the collector has not been able to confirm. The Dutch were making iron blades by the Thirteenth Century. By the late Eighteenth Century, skating was on its way to becoming a fashionable social pastime. Skating clubs opened in Philadelphia, New York and Boston in 1849, 1863 and 1912, respectively. The first skating performances and competitions also arose in the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

The Fenimore Art Museum tells this history with paintings and prints ranging from the sensitively rendered 1875 oil on canvas “Skating on the Schuylkill” by William Willcox (1831-1929) to a handful of Currier & Ives lithographs, one after Winslow Homer, summoning the gaiety and tumult of the rink. Régis Francois Gignoux’s (1816-1882) ink and tempera drawing “Skating in Central Park Near 59th Street” depicts the New York landmark before the installation of man-made ponds.

Belle Époque posters by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jules Chéret and other French masters capture the glamour of skating in the fin de siècle era and just after. A 1920 poster by Emil Cardinaux (1877-1936) shows St Moritz’s Palace Hotel. Button, who stayed there while training for the 1948 Winter Olympics, remembers it as “the epitome of Grand European hostelry,” with a guest list that included Jennifer Jones, Norma Shearer, the Duke of Alba and ex-King Peter of Yugoslavia.

These wood and brass skates in a style popular between the 1850s and the 1870s have heart cutouts on their stanchions.

A selection of skates, samples and advertising display pieces includes a pair of decorative steel blades manufactured by the Winchester Arms Company for Barney & Berry, the Springfield, Mass., retailer that patented its design for a clamp-on, all-steel skate in 1864. “Barney & Berry also offered mail order catalogs, complete with a series of figures with diagrams in the back pages for skaters to create. At the height of their popularity, Barney & Berry was producing 600,000 pairs of skates per year,” Button writes.

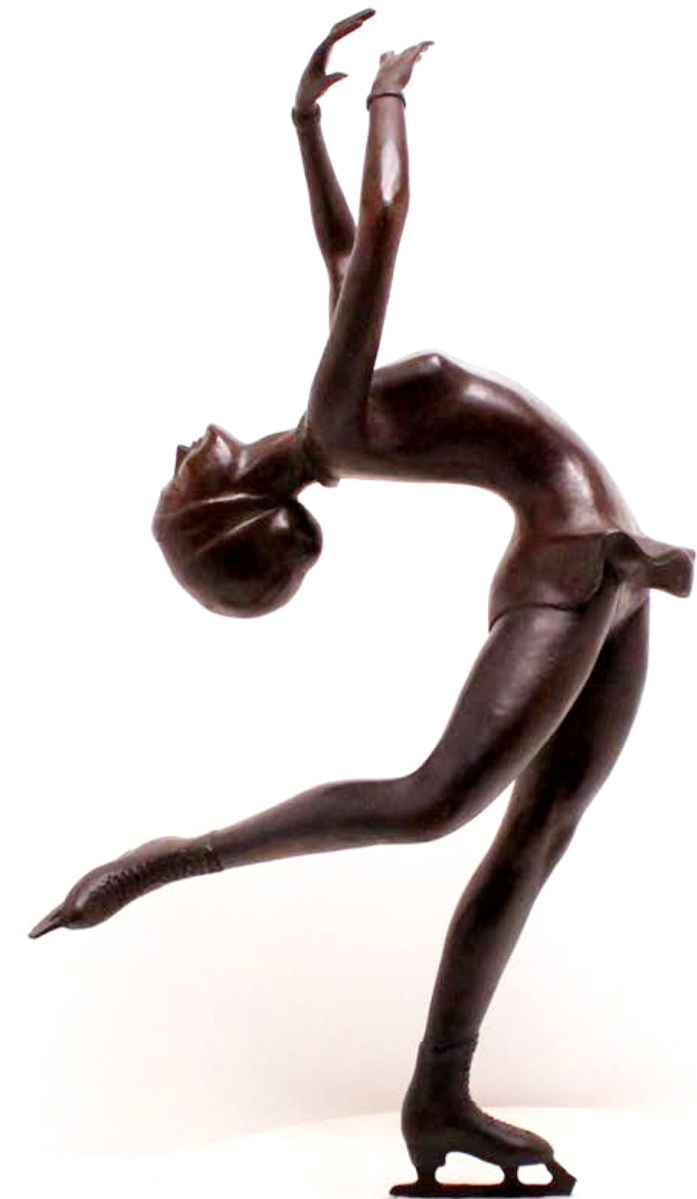

Button’s taste in sculpture ranges from traditional work of the sort epitomized by “Le Vrai Patineur,” the earliest known bronze depicting a skater performing a codified move, to the unconventional “Tonya,” Joel Corcos Levy’s satirical homage to Tonya Harding, the bad girl of competitive skating.

Every parent of a student athlete will melt at Button’s description of his childhood home, “crowded with nostalgic memories of amateur times.” Trophies, medals and tokens – among them, Button’s 1952 gold medal from the Oslo Winter Games – form a small part of the Cooperstown display. The most cherished of these remembrances, illustrated here but not in the show, is the trophy Ulrich Salchow (1877-1949), perhaps the greatest male skater of the early Twentieth Century, gave Button in 1947.

“I had lost the championship and come in second. Salchow gave it to me because he didn’t want me to go away without a trophy. I in turn gave it to Misha Petkevich, who gave it to Paul Wylie. We’ve made copies. It’s always intended to be given away,” says Button, who has never forgotten those who guided and nurtured him along the way.

“As a skater, Dick was a pioneer, setting new standards for the athleticism of the sport. And he did it with such dashing style and elegance. He jumped like no one else had ever jumped before. It was years before any younger skaters, with more advanced training techniques, could match him,” says JoJo Starbuck. “As a commentator, he was always on target with the focus of what was wrong or what was brilliant about a skater. Plus he had the ability to explain the complicated scoring system and compulsory demands to the home audience. He made it so exciting to watch and made you feel invested in each performance. As a friend, Dick is as true blue as they come. He’ll tease you and challenge you in a conversation, but he is ultimately there for you when you need him. He’s a great entertainer and brings diverse people together over fabulous food and wine for stimulating conversations. I love being around Dick Button. Sadly, they don’t make them like him anymore.”

Remembered for her grace and loveliness on the rink and off, Peggy Fleming has lent to the show the skating dress she wore for her gold-medal performance at the 1968 Winter Olympics. Fleming’s mother made the simple tunic, Button writes, remembering how the prodigy stood for hours on a box while the garment was pinned and stitched.

“My mother chose an unusual color, chartreuse, because the setting was Grenoble. She had read about the liqueur made by monks there. As I think about it many years later, it seems to me it was also the color of new growth and fresh beginnings,” says Fleming, adding, “I was 19, just a baby, really. All I wanted was a tight-fitting costume I could move in.”

Button’s own costume choices were bold, even transformative. He performed wearing a short, white mess jacket, unthinkable at the time, at the 1947 World Championships in Stockholm. “Such a break with tradition was necessary in order to be seen in an almost black setting. It caused a furor,” he wrote in Push Dick’s Button. The following year, he chose a black knitted jacket for the Olympic Winter Games to offset the white mountains of St Moritz. Prior to this time, male skaters typically wore dark suits more resembling street clothes.

Of late accompanied by his Airedale terriers Ceritto and Carlotta, Button has worked the meadows of Ice Pond Farm for 30 years. “I’m very good at pointing but Dick dives in and gets his hands dirty. He no sooner completes one garden than he starts another,” says Dennis Grimaldi. Anyone who knows Button’s philosophy of skating will find his gardens instructive. The formal symmetry of stone walls and hedges checks the unruly color and texture of loose perennials, just as diligent practice tempers the skater’s expressive exuberance. Well-clipped parterres trace a calligraphic pattern on the lawn, looking for all the world like the fresh-cut marks of a skater’s blade on the blackest of new ice.

“It’s the jumble of movement within the overall constraint of rigorous form,” Button explains.

In conjunction with “The Art of Skating,” Fenimore Art Museum is planning related programs throughout the season. On Saturday, July 15, from 2 to 4 pm, Button and skating stars Dorothy Hamill and JoJo Starbuck will lead “Fenimore on Ice” in the museum auditorium. The program includes a panel discussion on figure skating over the last century, screen clips of past Olympic and championship performances by the panelists, and personal anecdotes. The discussion will be moderated by Douglas Webster, the founding artistic director and choreographer of Ice Dance International. A choreographed performance by ice dancers from the organization is scheduled for 11 am to 2 pm on synthetic ice.

“I’m honored to be part of the exhibit and grateful that Dick shares the history of our sport, because he knows it best,” says Fleming, who is planning a visit to Cooperstown soon after the show opens.

The Fenimore Art Museum is at 5798 State Highway 80. For more information, 607-547-1400 or www.fenimoreartmuseum.org.