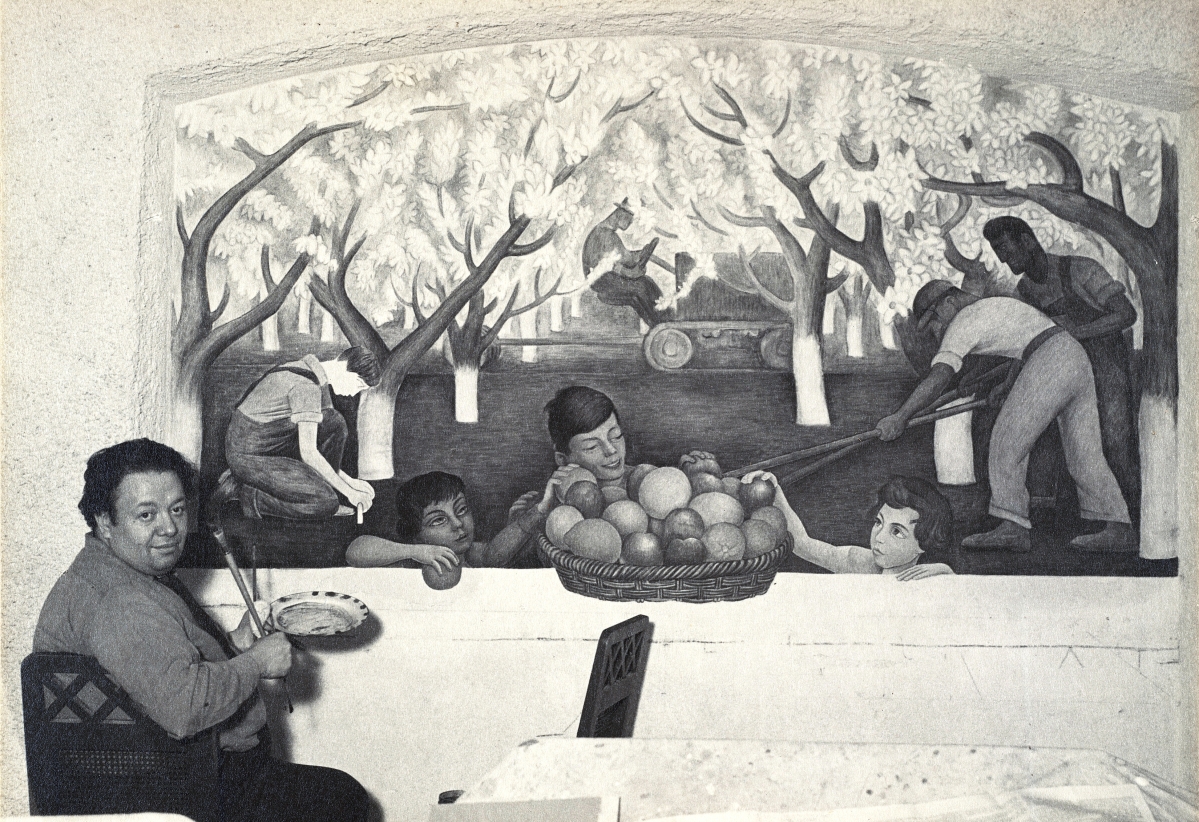

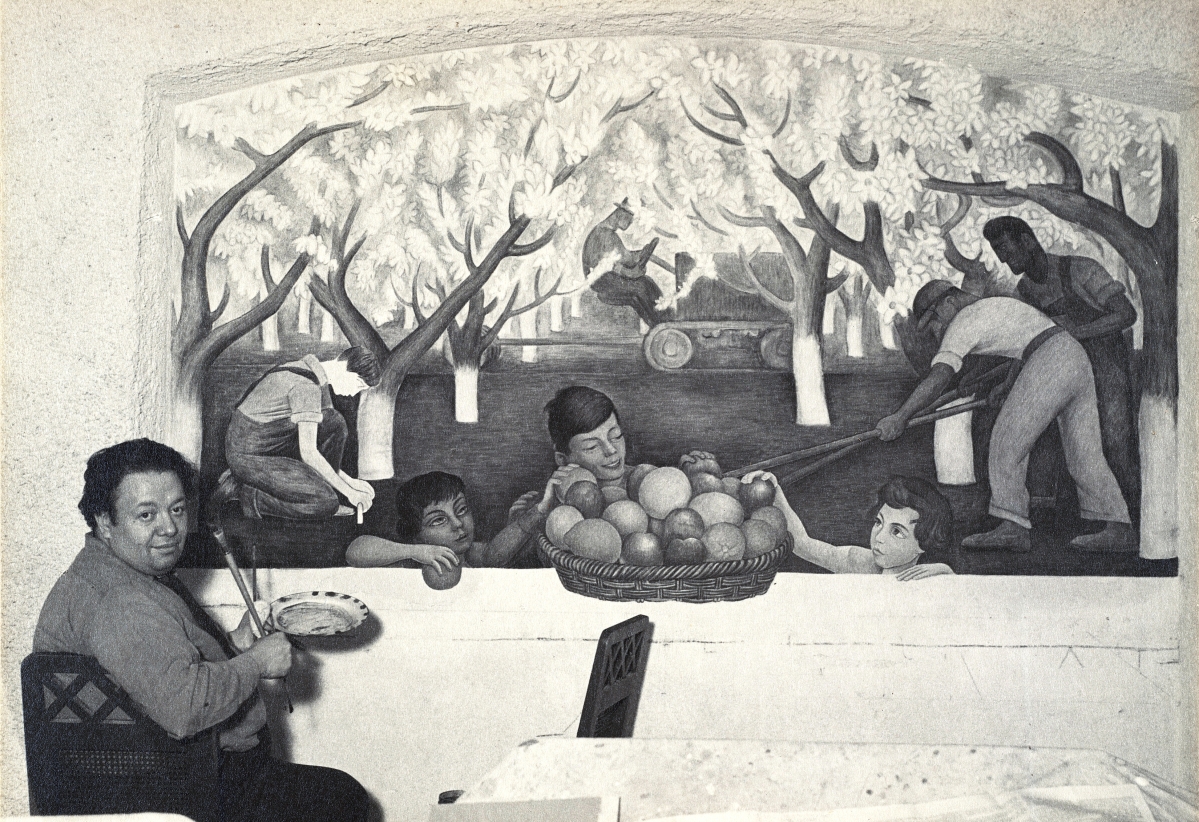

“Diego Rivera Painting the Fresco ‘Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees’ [formerly at Sigmund Stern House, Atherton, Calif.]” by Ansel Adams, 1930-31. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender; ©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

By James D. Balestrieri

SAN FRANCISCO – It’s not a stretch to say that San Francisco was Diego Rivera’s (Mexican, 1886-1957) “Golden Gate” to artistic success in the United States. But, as “Diego Rivera’s America,” the new exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) demonstrates, the United States was more than just the place where Rivera executed some of his greatest murals and found some of his greatest patrons. Notice I take care to say, “United States” rather than “America.” This is because Rivera’s “America,” as he lived and labored in the United States, took on a hemispheric meaning. His America was, or, rather, became, Pan-American. “I mean by America,” he said, “the territory included between the two ice barriers of the two poles. A fig for your barriers of wire and frontier guards.” Rivera’s Pan-America evolved over his years in the United States, rising out of his lifelong idealization of the agricultural and industrial working class and his conviction that art should not only celebrate the masses, it should be for the masses. He believed that society could be both prosperous and just – and that art was a key bridge to this end.

From 1907 to 1921, Rivera studied in Europe, in Spain and France, where he knew Picasso and fell under the spell of Modernism and the avant-garde, especially Cubism. At the same time, he took in Byzantine mosaics and classical and Renaissance frescoes. But post-revolutionary Mexico, in the person of minister of Public Education José Vasconcelos, called him back “to participate in the ‘decoration’ of federal buildings then underway, part of an official project to unify the nation in the wake of the Revolution.”

Rivera’s belief in workers as the source of transformative power caused him to turn away from the edges of modernism towards social realism and the mural – both as an expression of that power and as a way for workers to experience it as a civic art outside of the more forbidding environs of scholarly museums and aristocratic galleries. Echoes of the rounded, solid figures in Renoir, Cezanne and Gauguin make their way into Rivera’s aesthetic, as do the figures from Picasso’s “blue period.” As with those painters, there’s a classicism in Rivera’s figure work, an idealization ideally suited to his allegorical intentions, even when it is clear that he is using specific people as models. Cubism remains part of his practice, however, in the perspective-defying structure of his major murals and the more subtle ways he plays with it in his easel paintings.

“Woman with Calla Lilies” by Diego Rivera, 1945. Private collection, United States; courtesy Galeria Interart; ©2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City; Scott Cramer photo.

On his return from Europe, Rivera also turned away from Europe, seeking inspiration in the Indigenous Peoples and arts of Mexico and the Americas. On trips through the Yucatan and especially Oaxaca, Rivera found the powerful matriarchs of the peninsula emblematic of traditional deities; these would become central to his work. As curator James Oles writes in his catalog essay, “From Murals to Paintings: Scenes of Everyday Life,” Rivera adopted “the powerful albeit mythicized figure of the Tehuana, famed for her dominant role in the local market economy and her distinctive costume: a long, brightly colored cotton skirt, usually edged with a white ruffle, and a short, embroidered blouse (huipil). Reflecting centuries of cultural exchange, and actually more Victorian than Zapotec, the costume was nonetheless thought to preserve a deep Indigenous presence – what Rivera referred to as the region’s “classical past.” His idealization of the Tehuana was part of a broader cultural phenomenon in which women from distant locales – Andalusia, Algeria, Tahiti – were recast and objectified by European artists, writers and intellectuals, almost invariably men. But for Rivera these images of Tehuantepec also served a nationalist project that quickly transformed the Tehuana from a local type into an enduring symbol of Mexican identity.” (cat. p. 37)

The rhythms of work, ceremony and the natural world, and vegetative metaphors dominate Rivera’s easel paintings and “portable frescoes.” Repeated postures, shapes and a restrained palette express what he saw as the Indigenous, chthonic origins of his Pan-American art. In the late 1920s, Rivera made his first visit to the Soviet Union. Afterwards, he would graft industrial labor onto campesino forms. Factory workers in his paintings would be just as kinetic – but bluer, colder, steely and more angular.

Rivera was an instant star in the United States – as was Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907-1954). Rivera’s fate and Kahlo’s were intertwined then, even as their fame seems to be today. But where Rivera’s murals, which were intended to convey specific messages of progress and solidarity, required the patronage of the wealthy, Kahlo’s easel-sized excavations of her psyche and experience hewed more closely to modernism – especially Surrealism – and their very allusiveness, and elusiveness, ensured their avant-garde allure to collectors.

“Dance in Tehuantepec” by Diego Rivera, 1928. Collection Eduardo F. Costantini, Buenos Aires; ©2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Nevertheless, in his public art, Rivera sought to express his solidarity with the proletariat and to include critiques of capitalism and colonialism. This led, famously, to his dismissal from the commission to paint the murals at the new Rockefeller Center when he portrayed John D. Rockefeller as a top-hatted sybarite. At the same time, as Oles states, Rivera modified, and mollified, his politics in his gallery works: “Although many of Rivera’s paintings foreground the labors of the working class, they generally avoid references to social conflict or radical politics. He understood that collectors and dealers in the states preferred tranquil images of traditional Mexico that might serve as antidotes to the stresses of the urban, industrial age, especially during the Depression.” (cat. p. 36)

Still, Rivera tucks his politics even into a mural for a private California home. In “Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees,” 1931, the grandchildren of the artist’s patrons, Sigmund and Rosalie Stern – who were already enthusiastic collectors of Rivera’s paintings – enjoy the fruits of the earth, while Mexican laborers till the soil and tend to the trees in the background. Yet these laborers are not only responsible for the bounty enjoyed by the children, they are closer to the earth, under the beautiful umbrella of white almond blossoms. The Edenic setting honors and hallows their work without overt reference to distinctions of race, nationality or class.

Through his devotion to the ideal, in paintings such as “La tortillera (The Tortilla Maker)” (1926); “La bordadora (The Embroiderer)” (1928); and “Weaving” (1936), Rivera avoids any of the trapping – and traps – of the picturesque. Neither voyeuristic nor journalistic, these paintings, like “Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees,” sanctify the lives and labor of ordinary people, women in particular. In each painting, there is a sense of traditional cultural practices – lifeways, we might say – carried on and handed down in an unbroken continuum. A collector might purchase one of these and hang it on a wall for its apparent simplicity and generous beauty. But underlying those surfaces is the thrum of deep time, time tied to the seasons and cycles of the natural world. It’s a sound that many – if not most – viewers perceive only faintly, marking time in a dance that modernity excludes them from.

“Tehuanas in the Market” by Diego Rivera, 1935. Collection of the Tobin Theater Arts Fund; ©2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City; photo courtesy McNay Art Museum.

“Dance in Tehuantepec” (1928) and “Tehuanas in the Market” (1935), put us in the position of onlookers with an urge to join the dance or break into the powerful circle of women at the market. But how can we? “What would we have to do?” Rivera seems to want us to ask ourselves. “What preconceptions would we have to give up? What philosophical sea changes would we have to undergo?” The paintings find us wanting – and leave us wanting more.

Desire is so much a part of art; wanting to feel and share in the rhythms of Rivera’s paintings goes a long way towards understanding his enduring appeal. Even in a work such as the 1935 painting, “The Flower Carrier,” where a man on his knees under the weight of a basket of flowers is helped to his feet by a woman, struggle assumes a saintly aspect. Rivera paints the flowers in a cone shape, filling them with a Renoiresque light and lightness, as if they are shedding weight with each passing moment. The shape of the man’s yellow sling runs straight into the shape of the woman’s light blue shawl, as if they are merging, becoming one, as if she is taking some of the weight from him. The man’s palms, knees and legs cling to the earth, but Rivera subtly distorts the perspective, tilting the picture plane, as if the earth itself is tilting to help him rise. The pastels and earth tones that dominate the painting recall Giotto’s frescoes in the Arena Chapel and the manner in which Rivera works edge-to-edge recalls classical friezes.

With the rise of fascism, and the brief marriage of convenience between capitalism and communism against fascism, Rivera seemed to see hope in the union of north and south in the Western Hemisphere, embracing a Pan-Americanism in his thought and art. Calla lilies, for example, appear throughout Rivera’s career – they are a theme, a leitmotif of nature’s generative power. “Woman with Calla Lillies,” painted in 1945, just as World War II was coming to a close, seems, however, to go beyond earlier incarnations of the subject. Here, a woman on her knees embraces a wrapped bundle of calla lilies, a life-affirming answer to the bundle of dead sticks, the fasces, that the Axis Powers adopted as their symbol. This can be the world, Rivera suggests, all of us, together. Yet they are cut flowers – the stem ends flank the woman’s feet – indicating the ephemerality of the moment, this moment, when the world might truly be as one. The woman, turned away, seems to be about to turn to us, but her gaze is something we may also have to earn.

Like all Camelots, the moment proved short-lived. Rivera would live to see the World War become a Cold War and allies become enemies. But art always dreams, and the dreams of art are always worth remembering.

“Diego Rivera’s America” will be on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through January 2.

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is at 151 Third Street. For information, www.sfmoma.org or 415-357-4000.