Installation view of “All Sorts of Chairs and Joiner’s Work: Pennsylvania Furniture from the Dietrich American Foundation,” on view through December 2023 at Historic Trappe’s Muhlenberg House. Gavin Ashworth photo.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

TRAPPE, PENN. – Historic house museums are a wonderful time-capsule of items connected with a specific time and place but can feel static unless pains are taken to expand the context for the objects presented within. Thanks to a loan of 20 pieces of chairs and case furniture from the Dietrich American Foundation, Historic Trappe presents, in the Henry Muhlenberg House opening in March through 2023, “All Sorts of Chairs and Joiner’s Work: Pennsylvania Furniture from the Dietrich American Foundation.” The pieces, shown in a small gallery adjacent to the museum’s furnished period rooms, are examples that largely predate the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Century furnishings in Historic Trappe’s collection. It provides an opportunity for visitors to see the style that influenced the decorative arts contemporary to those acquired and used by early residents of Trappe, including the families of pastor and the patriarch of the Lutheran church in the United States, Henry Muhlenberg (1711-1787) and his descendants.

“We’ve had an ongoing relationship with the Dietrich American Foundation for years,” said Lisa Minardi, director at Historic Trappe, when asked how the exhibition came about. “Debbie Rebuck with the Dietrich Foundation contacted me a few years ago, said they would have some additional pieces available for loan, and was I interested in using them. I thought it was a great opportunity to put the furniture we already had into a greater context.”

“It’s really such a great collaboration between the foundation and Historic Trappe’s Pennsylvania German collection and the Muhlenberg House where we already have a number of objects on loan,” Rebuck confirmed. “As a lending library of objects, we are really thrilled to be able to loan to institutions as they are building or developing their own collections. Lisa is so great at teaching and connecting with students and collectors, at pointing out the differences and similarities among objects, so we are thrilled to have these Pennsylvania furniture pieces in an exhibition there. Because it’s a small gallery and exhibition, and it’s a more informal setting than one you’d have in a big museum, there are opportunities to engage viewers in ways you can’t otherwise.”

Another aspect of that informal setting allows for visitors to get slightly closer to furniture than they would be able to in a more restricted museum setting. While touching and handling are not allowed, the ability for visitors to view pieces more intimately, and in many cases in the round, has made the experience decidedly more engaging, according to Historic Trappe board member, Tom Musselman, who has been helping give tours that include the Dietrich loan furniture. He shared some observations after the exhibition was opened for a special preview prior to the official opening this spring.

Side chair, labeled by William Savery (1721/1722-1787), Philadelphia, 1765-80, maple, cedar, rush. Dietrich American Foundation, Gavin Ashworth photo. The most notable aspect of the chair is the remains of Savery’s printed label underneath, advertising “All Sorts of Chairs and/ Joiners Work/ Made and Sold by/ William Savery/ At the Sign of the/ Chair, a little be/low the Market, in/ Second Street/ Philadelphia.”

“The response has been very positive. Most visitors have been very impressed with the scope of the Dietrich furniture. We have had collectors who have compared things on the floor with things on their ‘wish list,’ while the casual, perhaps less informed, observer, is very impressed by the quality and scope of furniture.”

Minardi was assisted in the exhibition by Tom Stokes, a budding scholar and collector who, as it happens, is a descendant of Henry Muhlenberg’s son, minister and politician, Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg (1750-1801).

“On an academic level, Historic Trappe focuses on Pennsylvania German arts, architecture and decorative arts. This exhibition shows the importance of Philadelphia’s English or Anglo inspired furniture and its crossover, for example its influence on the set of chairs owned by the Muhlenberg family that were made by Leonard Kessler,” Stokes said.

The exhibition takes its name from the remnants of William Savery’s (1721/22-1787) label affixed underneath a rush-seat side chair, which advertised “All Sorts of Chairs and/ Joiners Work/ Made and Sold by/ William Savery/ At the Sign of the/ Chair, a little be/low the Market, in/ Second Street/ Philadelphia.”

Henry Muhlenberg House, located at 201 West Main Street in Trappe. The house was built circa 1750-55 for Jacob Schrack Jr, son of Trappe’s founder. The Muhlenbergs, who had lived in Trappe in a different house from 1745 to 1760 before moving to Philadelphia, purchased the Schrack house in 1776 and returned to Trappe. Henry and Mary Muhlenberg sold the house in 1787 to their son, Peter Muhlenberg, and his wife Hannah, but continued living there as well. The house is now interpreted to reflect this multigenerational household. It contains seven furnished rooms and an exhibition gallery. Gavin Ashworth photo.

Though the chair itself is fairly modest in its outward appearance, it is just one of a handful of known pieces with the label of the prolific and well-known craftsman, making it an important inclusion in the exhibition.

The Dietrich American Foundation loan includes two other pieces marked by their maker, including a Windsor fanback armchair made in Philadelphia between 1755 and 1760 that bears the brand of Thomas Gilpin (1700-1766). Not only is the chair the only Windsor in the exhibition but Gilpin is also recognized in the exhibition as having been one of the first known Philadelphia makers to mark or brand his chairs. The chair retains traces of its original green paint under later black and red-painted surfaces.

A chest of drawers is signed by William Beakes III (1691-1761) and attributed to Burlington County, N.J., 1721. Beakes, a Quaker joiner in the Delaware Valley, apprenticed with joiner William Till (1676-1711) in Philadelphia until 1711. His signature appears in an inscription on one of the upper drawers, “Sarah Thorn her Draws/made by Wm Beakes this 14 of 12 mo 1720.” [The seeming discrepancy between 1720 and 1721 is explained by the difference between Julian calendars, used at the time, and the Gregorian calendar currently in use.]

Stokes, speaking from the vantage point of having been able to thoroughly examine each piece from the Dietrich American Foundation, notes that several successive generations that owned the chest – descendants of Sarah Thorn – all wrote their names on the chest.

The dining room is furnished to reflect the multigenerational nature of the household. The chairs are from a set of 12 made for Henry Muhlenberg in 1763 when he was living in Philadelphia; he brought these chairs with him when he retired to Trappe in 1776, and they descended in the family after Henry’s death in 1787. The piano, made by Charles Albrecht of Philadelphia in the 1790s, is similar to one that Peter Muhlenberg purchased from Albrecht for his daughter Hetty. Gavin Ashworth photo.

Other pieces in the exhibition offer evidence and tantalizing glimpses of provenance. A diminutive walnut high chest features a paper label glued to the backboard of the upper case that reads, “This chest of drawers was made for Sarah Pleasants in about the year 1780.” The Pleasants were a prominent Quaker family, and the exhibition asserts that this object helped acclimate Sarah to the “function and fashion of domesticity in Eighteenth Century Philadelphia.”

“Parrish,” the name branded on the rear seat rail of a Philadelphia-attributed mahogany side chair with pendant tassel that dates to circa 1765-75 suggests the name of an early owner, while the Roman numeral “III” stamped on the front indicates it was part of a set.

The carving that is a cornerstone of Philadelphia craftsmanship is witnessed on eight examples in the exhibition, including two chairs with tassel backs, both third quarter Eighteenth Century, an early, circa 1745-55, walnut compass-seat side chair with shell-and-scroll carved crest and inset carved shell on the crest rail, not to mention a side chair with carving attributed to the Garvan Carver is brought into particular focus in its period setting at Historic Trappe.

“What distinguishes our exhibition is that, within a furnished house museum that gives the original context to the pieces, one of the remarkable things we experienced installing it, is the pieces have incredible carving that become so much more defined when you see it in a room with windows and natural light. It’s a hugely different experience to viewing chairs in a museum with overhead lighting. The Dietrich furniture is the last stop on the tour after seeing the rooms furnished as the Muhlenberg family lived there; it puts it all into context,” Minardi explains.

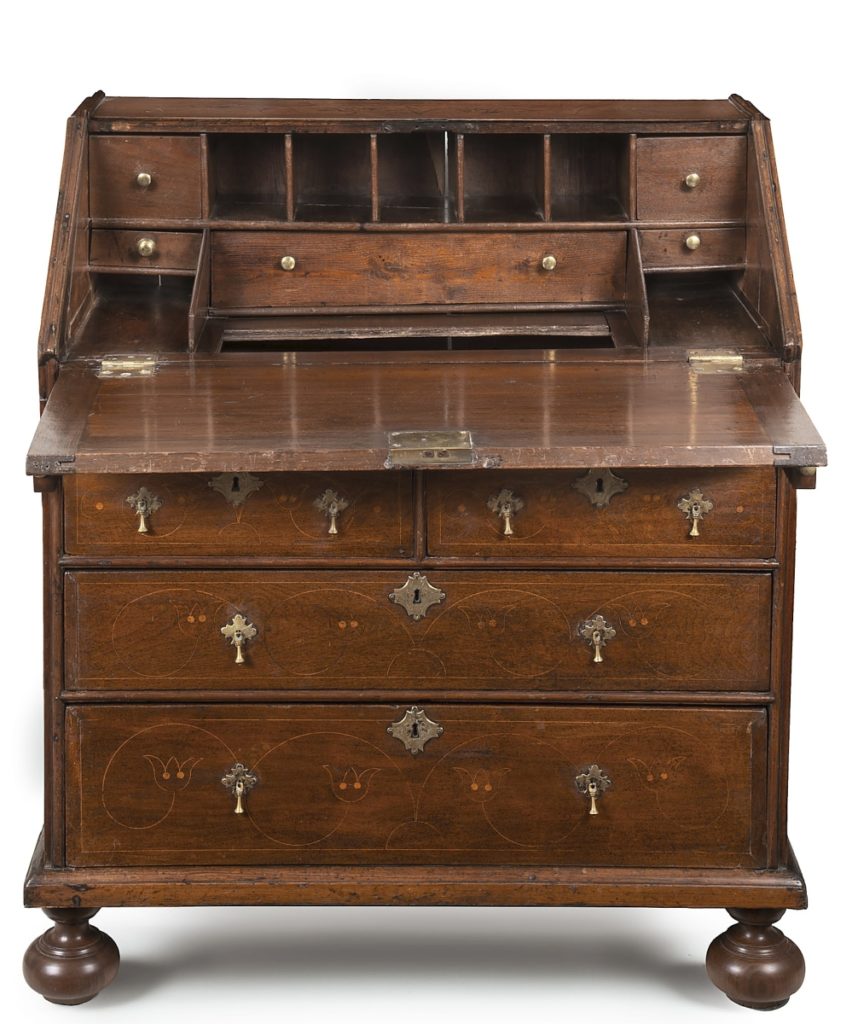

Slant-front desk with line-and-berry inlay, probably Chester County, Penn., circa 1720-40, walnut, pine, cedar, gum, oak, brass. Dietrich American Foundation, Gavin Ashworth photo. Emerging in the early 1700s, line-and-berry inlay became a popular form of decoration among Quaker furniture makers in Chester County. The inlay on this slant-front desk was laid out with a compass and includes tulip-like flowers with berries or dots. This is the only known line-and-berry inlaid desk that is ornamented on the drawers, lid and top.

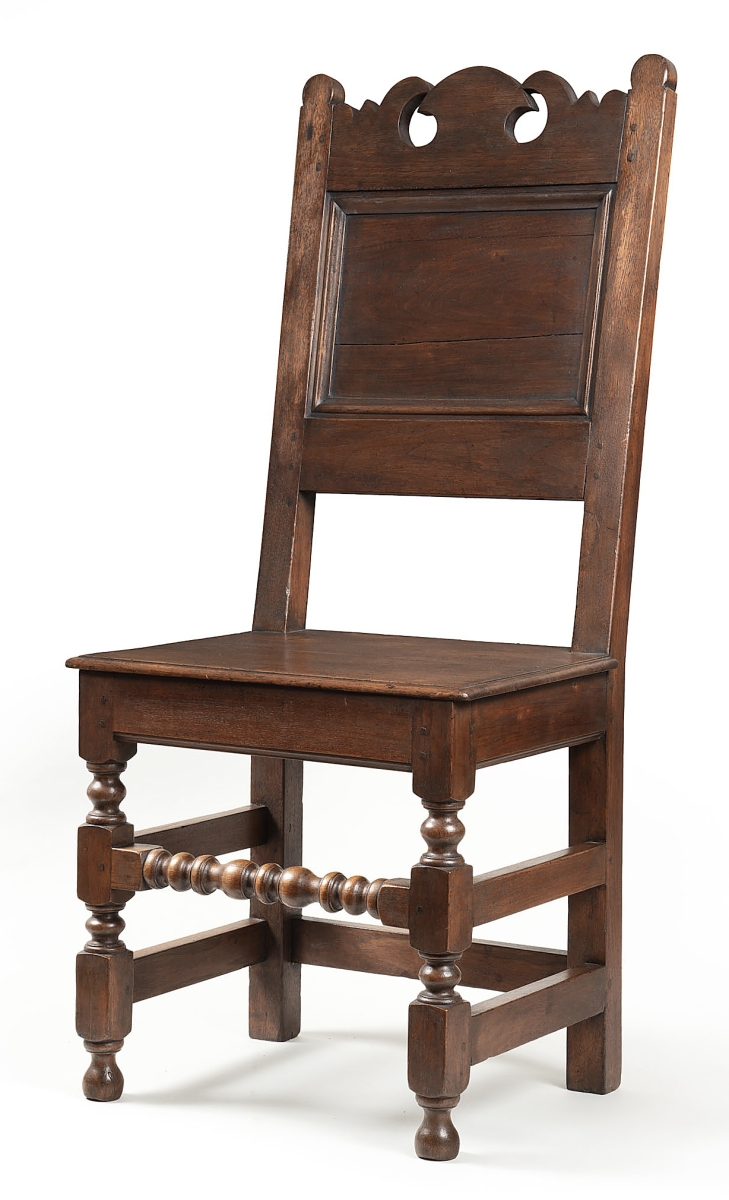

The presence of a wainscot chair is exciting for Minardi, who said that while there are quite a few extant examples, most are in museums so not very accessible. “There are really important academic and historical connections between Philadelphia and rural regions that can’t be understated and are exciting to me.”

While a closing date for “All Sorts of Chairs and Joiner’s Work: Pennsylvania Furniture from the Dietrich American Foundation” has not yet been set, Minardi says the exhibition will be on view through 2023. Tours are available by appointment starting in March.

Historic Trappe’s headquarters is at 301 West Main Street. For information, www.historictrappe.org or 610-489-7560.