“Lamentation over the Dead Christ” by Donatello. ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

By James D. Balestrieri

LONDON — Art history brings history to life through art and art to life through history. In art history, art is both lens and subject, as is history. Sometimes, however, it is instructive to imagine artists, not in their own times, but in ours. Such is the case with early Italian Renaissance sculptor Donatello (born Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, 1386-1466), who has been called the world’s greatest sculptor, and who might be said to have propelled Italy into the much more familiar era of Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. “Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance,” the new exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum, makes it clear that though Donatello is not as well-known as many other artists of the Italian Renaissance, he ought to be.

Donatello combined restless, fearless invention, a desire to find — and exceed — the limits of the media he worked in and freely mixed, and a transformative absorption of the classical and medieval past. Bringing him forward to 2022, and imagining him as, say, a filmmaker, we can see him mashing up traditional film and digital forms, claymation and NFTs, live performance and apps, and creating forms that might seem impossible to us — a podcast in marble, perhaps.

Born in Florence on the hinge between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, at the moment when the Medici family were beginning to exert their authority, Donatello’s talent dovetailed with the Medici interest in projecting refinement — and power — through the languages of art. In a revelation, at least to me, Donatello, along with many other artists of the period, began his career as a goldsmith. Understanding the qualities and properties of metals, gems and stone, processes of casting and chasing, and the mixing of media to produce specific effects on a small scale gave Donatello essential skills — drawing, modeling, carving — that he would employ throughout his career. Donatello trained in the studio of Lorenzo Ghiberti, whose bronze doors for the Florence Baptistry are considered a key point of origin for the Renaissance. In Ghiberti’s studio, Donatello would have seen Roman and Etruscan objects. This rediscovery of the classical past, antiquity as an inspiration, is, of course, a hallmark of the Renaissance. What is interesting about Donatello is that he didn’t engage in imitation, choosing instead to fold antiquity into Gothic and medieval forms and transforming these into a style all his own.

Still, at 17, in 1401, Donatello went to Rome, no doubt yearning to see some of the ruins of Rome, just then being unearthed, for himself. It is said he traveled with Filippo Brunelleschi, the principal architect of the Italian Renaissance, and one can only imagine these two young titans on the road together, dreaming the forms of the classical past into what Giorgio Vasari would call, in his 1550-68 opus Lives of the Artists, “the modern.”

_victoria_and_albert_museum_london-768x1024.jpg)

“An Adoring Angel” by Michelozzo. ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

There are parts to the ferment that led to what Vasari called “the modern” — and what we call the Renaissance. A renewed focus on the human, on humanism, is another key. Within the church, the otherworldliness of the mystery of Christ was brought down to the level of the Passion play. Liturgy took on the aspect of theater and the emotions of the figures in the New Testament as the physical body expresses them begin to emerge in art. At the same time, this notion of space as theater enters into the thinking of Donatello and others as they create works with their specific uses and sites in mind.

Donatello, perhaps above all others, breathed in this heady air, taking every project as a new challenge requiring new invention, and never really repeating himself.

In a late devotional bronze, “Lamentation over the Dead Christ,” Donatello deploys a mix of roughs and smooths in a tableau of linked figures weeping, tearing their hair out, gesturing histrionically. The face of Mary, as she holds the limp body of her son, is heavily lined, indicating her grief as the death of her son ages her beyond the beatific image we see, for example, in Michelangelo’s “Pietà.” Here a kind of ill wind agitates locks of hair and the folds of the garments; we can imagine a director composing this on stage. As the catalog suggests, the voids between the figures may have been left for a “glass, cloth or stone” (cat. p. 220) backdrop, perhaps a translucent red, to make an alchemical association between bronze and blood, and indicate the sacrificial aspect of the story.

As further evidence of his interest in transforming and transformative forms, Donatello also sculpted a “Crucifixion with a Christ” figure that could be taken down and removed from the cross. The figure of Christ itself had movable arms so that it could be carried and displayed, arms at its sides, in a very human manner. As Timothy Verdon, in his catalog essay “Devotion and Emotion” argues, Donatello “from the beginning of his career to its end exploited stylistic naturalism in religious subjects to communicate pathos.” (cat. p. 50).

“Pazzi Madonna” by Donatello. Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin. Photo by Antje Voigt, Berlin.

To serve this ideal, Donatello pushed the limits of materials and media, perhaps nowhere more than in the rilievo stiacciato (or schiacciato) marble relief technique that is his own invention (cat. p. 15) as gossamer. These subtle, delicately carved shallow reliefs seem derived from the artist’s work in jewelry, like cameos scaled up to the size of paintings. In works such as “Ascension with Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter,” the sublime “Pazzi Madonna,” and the ethereal “Madonna of the Clouds,” Donatello finds a kind of gossamer ephemerality in the solidity of marble, often barely carving and incising the stone, as if asking not, “How much can we do to make art and elicit emotion?” but “How little can we do to achieve the aims of our art?” In the “Ascension,” the wind blows, the apostles process (in the twin senses of proceeding and of making sense of this sacred transferal of authority), and even the angels can only watch in awe and wonder. In the “Pazzi Madonna,” Donatello introduces perspective, a “science of vision” developed by his friend Brunelleschi. Now we see the Madonna and Child through a carved window, forehead to forehead in a tender, thoroughly human moment, one we might imagine seeing by accident, in passing, receiving grace in a glance. Lastly, the “Madonna of the Clouds” is a mystery of the artist’s own making, a metaphor outside the traditional temporality of the scene. Once again, Donatello wrests the lightness of wind and clouds from barely carved marble as the angels fly in and out of the scene.

The angels in the scenes recall Donatello’s spiritelli, angels making music to celebrate the savior and the revelations of Christianity, and the exhibition notes that Donatello practically invented the trope, drawing it from classical faun forms and Cupids. As examples, consider the “Spiritello with Tambourine,” expressing holy joy, alongside the erotically charged, earthy, enigmatic “Attis-Amorino.” Despite their differences, the symmetry of the poses shows the artist’s mind at work, making the distant past serve present ends.

Donatello, of course, worked large and in the round. An early “David,” for example, carved in 1408-09, “still shows medieval characteristics in the figure’s artificial sway and exaggerated neck, but the forceful emphasis on the alert and idealized male youth largely determined the mythic personification of Florentine heroes in the centuries that followed” (cat. p. 106). It’s the stillness that’s medieval. A studied stillness meant to contain emotion, to subordinate it to higher aims and powers. By the time Donatello casts his most famous “David” in 1435, animation of the body to convey the inner life of the individual — which, in turn, reveals a common humanity — will supersede medieval stillness.

Perhaps also arising from his apprenticeship as a goldsmith and from an interest in the alchemy of combining and transforming elements, Donatello frequently enhanced humble materials, such as wood, terracotta and bronze, by gilding and chasing them, as in the “Reliquary Bust of San Rossore.” Individualizing the image of a Third Century Roman soldier who converted to Christianity and was martyred — no portrait of San Rossore existed, then or now — Donatello gives the saint a core of bronze, then gilds it with gold, signifying inner strength and resolve overlaid with the golden reward of faith. At one point, the eyes were silvered, perhaps to reflect San Rossore’s furrowed contemplation back to the viewer as a judgement, or question — “How strong is your faith?”

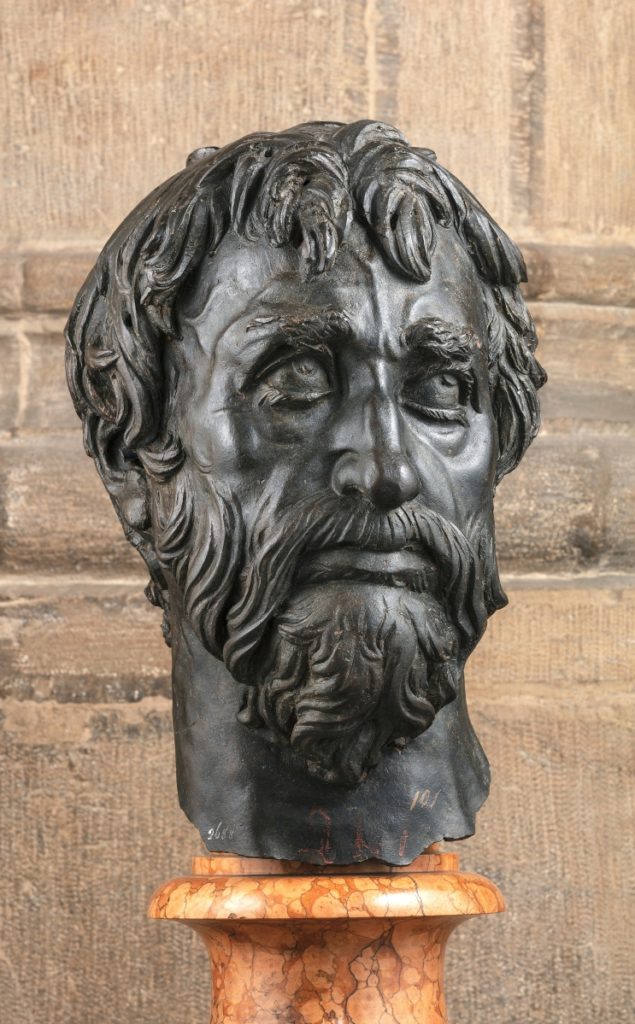

“Head of a Bearded Man, possibly a Prophet” by Donatello. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, courtesy of the Ministry of Culture. —Bruno Bruchi photo

The “Chellini Madonna” (circa 1450) brings us back to the idea of a podcast in marble. A bronze tondo of the Madonna and Child on a balcony or balustrade, with angels flanking them, this round form was meant to be reproduced for home devotions (Della Robbia would make these even more accessible in glazed clay forms), but Donatello’s bronze, given to his doctor — Chellini, as payment for treatment — is hollowed out and doubles as a mold, so that glass casts can be made from it and sold or given as gifts. Considering the scene, once again the viewer is catching a glimpse of a celestial event through an offset portal. The tondo is surrounded by “psuedo-kufic script,” that is, pseudo-ornate Arabic, which is not only decorative but suggests not only the artist’s awareness — however faint — of Islamic culture, but that mysteries of faith can happen anywhere. Light through the glass casts would, of course, indicate the purity of the Virgin Mary and the light of faith. As Alison Wright observes in her catalog essay, “The play between metaphor, matter and animation — in this case, between molded vessel, glass and Holy Spirit — is especially rich in Donatello’s sculpture.” (cat. p. 44).

Someone is always saying we are in a Renaissance of this or that — be it cuisine, fashion, the arts. The truth is, we’d like to believe that we live in a continual Renaissance. The very idea of the word conjures discovery, rediscovery, creation and fusion. What “Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance” shows us is that Renaissance requires observation, attention, and a fearless synthesis, not only of the past, but of everything that comes to hand or eye. Even more, Renaissance requires fearless imaginative forays into the future.

“Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance” was developed in collaboration with Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi and the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, and the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and is sponsored by Rocco Forte Hotels, with further support from Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne, Daniel Katz Ltd, Kathryn Uhde, the “Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance” Exhibition Supporters’ Circle, Tavolozza Foundation and the Henry Moore Foundation.

“Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance” will be on view at the Victoria & Albert Museum through June 11.

The Victoria & Albert Museum is on Cromwell Road. For information, www.vam.ac.uk or +44 20 7942 2000.

_victoria_and_albert_museum_london.jpg)

_victoria_and_albert_museum_london.jpg)

_2023._museum_of_fine_arts_boston.jpg)

_victoria_and_albert_museum_london.jpg)

_victoria_and_albert_museum_london.jpg)