By Justin W. Thomas

WASHINGTON, D.C. – In the collection of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institute there is a Nineteenth Century slip-script red earthenware jar from northern New York. The information written on this jar, decorated with flowers and inscribed in slip, represents a business and location that are largely unknown today: “Earthenware / Factory Champion Jefferson / State of New York.”

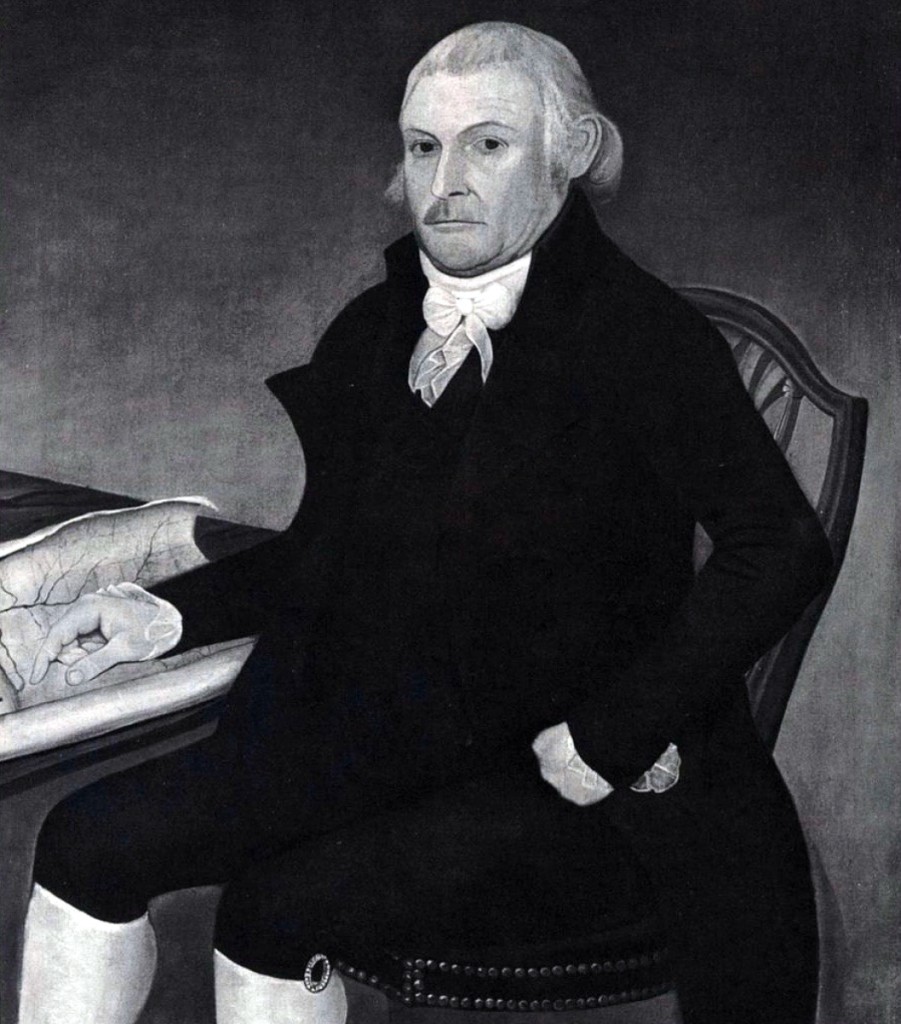

Champion, N.Y., was settled around 1798 in Jefferson County, and named after General Henry Champion (1751-1836), who served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War; he fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. The town was established in 1800 from part of Mexico (now Oswego) County, N.Y., on the northern frontier, not far from the shores of Lake Ontario and the Canada border. Early settlers hoped it would become the locale for the county seat.

When Champion was settled, it was a part of a movement that followed the American Revolution, when land throughout parts of upstate New York opened up for settlement, and men and women migrated from all over, including New England, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. Some of these migrations were a result of a religious quest, seeing that at the time, parts of New York were engulfed with new religious movements, such as Mormonism.

The formation of these new settlements and towns presented opportunities for potters to relocate and operate their own businesses. According to the information on file with the National Museum of American History, “The jar was made by Jared Dewey (b about 1792) who appears along with Herman Dewey in Champion Township in the 1820 New York State Population Census.” He is also listed as an earthenware potter in Jefferson County, N. Y., by Winterthur’s Library, based on information obtained from the Decorative Arts Photographic Collection before 1920.

Very little is known about Jared Dewey’s life or his involvement with the pottery industry, although he shows up alongside Herman Dewey again in the 1830 United States Federal Census, living 18 miles southwest of Champion in Rodman. In addition, his name appears in the 1850 United States Federal Census, this time residing eight miles west of Champion in Rutland, N.Y., cited as being 58 years of age. He is listed as a farmer; there is no evidence that he continued to manufacture pottery once he left Champion, even though the combination of farmer/potter was a regular means of employment throughout rural America in the 1800s. His farm was valued at $500 and his farm equipment $30. He also owned a horse, cows, sheep and swine, as well as bushels of wheat, Indian corn and oats.

While living in Champion, Dewey may have been an employee of the Brown family, who owned the first and perhaps only pottery that operated in the town. James Brown (1772-1857) was a native of Warren, Worcester County, Mass.; his wife, Anna Brown (1778-1858) was born in Bennington, Vt. They had four children, including Elam Brown (1802-1881), who was born in Bridgewater, Oneida County, N.Y., on December 13, 1802. He was the eldest son. The family moved to Champion in 1803, where James’s name is found among the earliest settlers of the town. He engaged in farming, opened a public house, built a gristmill, carried on a pottery business, and manufactured brick. Like Dewey’s story, not a lot of information is documented about the Brown family pottery, but it was likely a company created to supplement the family’s yearly income as farmers.

According to authors Samuel Durant and Henry B. Peirce, who published the book, History of Jefferson County, New York in 1878, “Elam worked with his father on the farm and in connection with his other business until he was 40 years of age, receiving only a limited opportunity for an education from books, but became well-schooled in business pursuits.” This appears to be the only information ever published about the Brown family pottery.

But there may have also been a lasting friendship formed between Elam and Jared Dewey after he left Champion. For instance, in 1843, Elam married Mary Waldo (1819-1859) of Rutland, they had two sons, and Dewey may have been living in Rutland at this time. Unfortunately, his first wife died in 1859, and he married Agnes Pease (d 1868) of Rome, N.Y.

The fact that the Browns seem to have been the only red earthenware manufactory based in Champion, for upwards of 40 or more years leads one to believe that the advertising jar owned by the National Museum of American History may have been manufactured at their business.

The history of this business is intriguing; for example, James and Anna Brown first migrated from New England to Madison, N.Y., in 1790. He may have already been a trained potter at this point, but he may have also learned the potter’s trade after he moved to New York. This would not have been an anomaly since other documented potters who migrated to New York in the Nineteenth Century are known to have acquired their craft after they arrived. The 1790s would have also been very early for business for this area; there is hardly any documented production before 1800 in areas not associated with downstate New York and the Hudson River.

The style of the slip found on this jar is considered rare for upstate New York during this period, with only a small group of potters known to have been involved with any type of slipware production. Some of those businesses include the Nathaniel Rochester (1752-1831) Pottery in Rochester, Heber Kimball (1801-1868) in Mendon, Elijah Cornell (1771-1862) in DeRuyter, and John Betts Gregory (1783-1842) in Clinton.

The form of the jar is similar to a small group of slip-decorated red earthenware jars generically attributed to upstate New York today, with little information to support a more specific location or business. And those forms are similar to a jar heavily incised with branches and flowers, where the incised lines have been infilled with slip. Furthermore, the jar is adorned in slip with eagles and a peacock.

The history behind the Smithsonian’s jar and red earthenware production in Champion is an excellent example of how there is a lot yet to be learned about early pottery production in America. Not only is this jar skillfully thrown and decorated in slip-script, but also it was manufactured in a community of nearly 2,100 people in 1820. It is because of the script that this jar can be identified to a specific location – and without this information, this jar would likely be misinterpreted for production from somewhere else. The importance of this jar should not be understated; this piece of living history represents the town Champion, its early settlement and a local pottery business, which this writer suspects is not the only example of surviving Champion red earthenware in existence today. The Smithsonian National Museum of American History is at 1300 Constitution Avenue, NW. For further information, www.americanhistory.si.edu.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are courtesy National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institute.