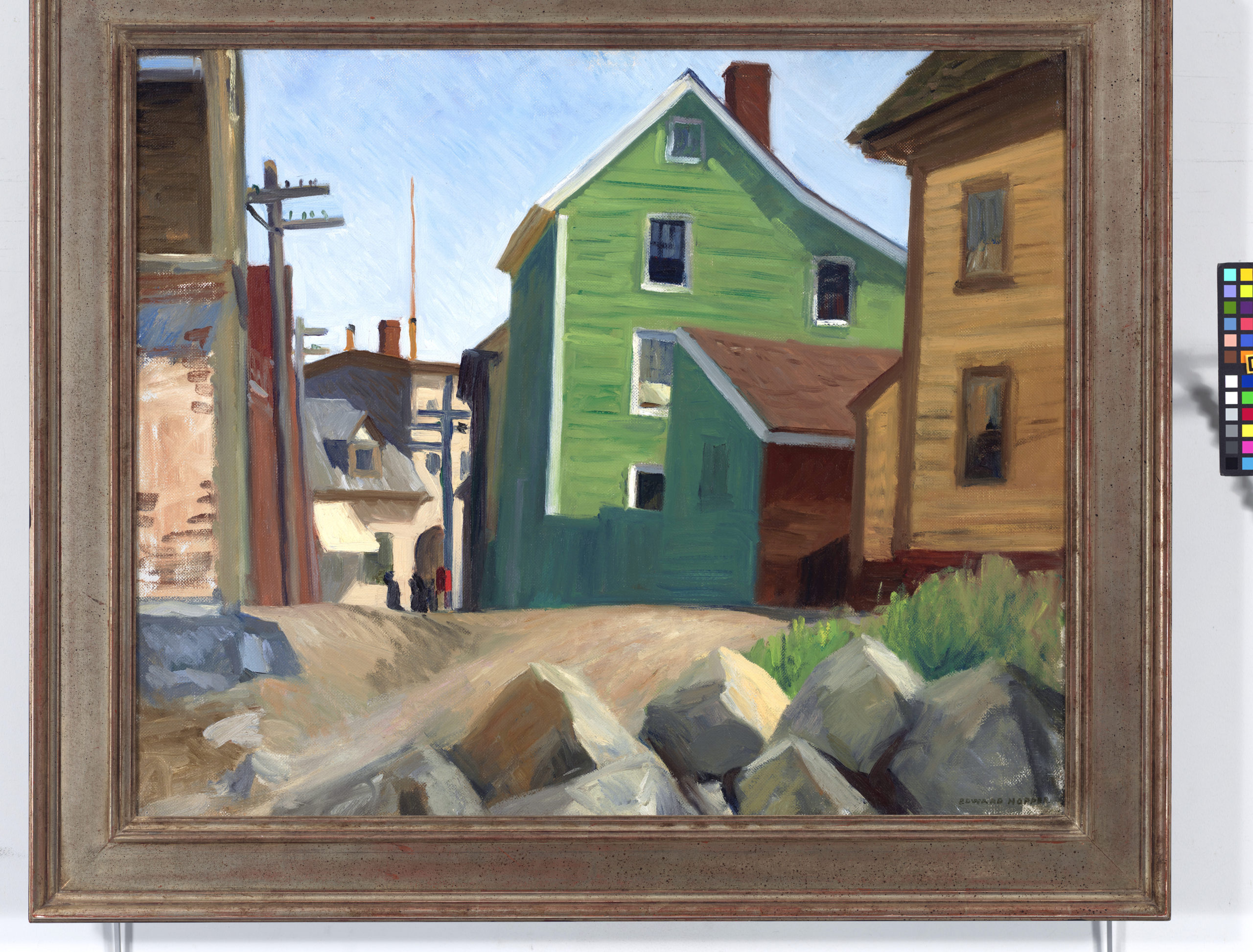

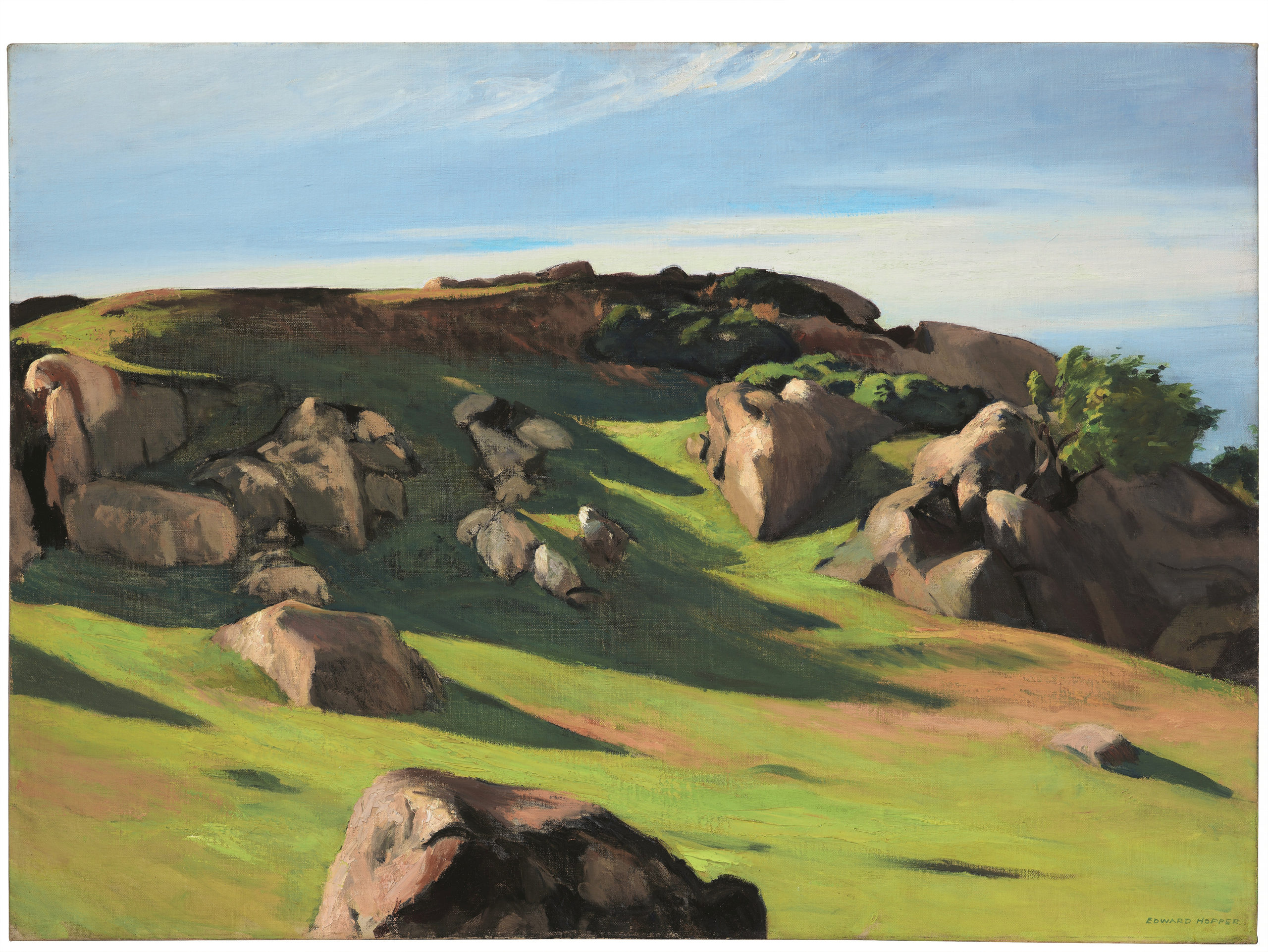

“Hodgkin’s House” by Edward Hopper, 1928, oil on canvas, 28 by 36 inches (71.1 by 91.4 cm). Private Collection. © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYC.

By Kristin Nord

GLOUCESTER, MASS. — It was on a rainy day in October that Elliot Bostwick Davis, PhD, and her longtime friend and colleague, Cape Ann Museum’s director, Oliver Barker, retraced the routes Edward Hopper (American, 1882-1967) had painted during his summers on Cape Ann. The two had begun to think about how they might celebrate the 100th anniversary of Hopper’s formative summer there. Many of the homes that Hopper immortalized are still found on Middle, Washington and Prospect streets, and the city itself was about to mark its Quadricentennial.

Davis said recently that she was searching for a hook for the exhibition and found it in the sea of unanswered questions about Josephine Verstille Nivison (American, 1883-1968), the artist who became Hopper’s love interest and later his longtime wife, muse and model. As it turned out, Nivison is the unsung hero in this chapter of the Hopper story, and “Edward Hopper & Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape,” on view at the Cape Ann Museum through October 16, should go a long way toward correcting the record. She played a crucial role in Hopper’s artistic development at this time of his life — and her connections in the New York City art world soon opened doors for him.

Until then, Hopper had earned his living as a commercial illustrator and etcher; at 41 years of age, he was still struggling to find his artistic voice. Despite painting in Gloucester in 1912 and in Maine for six summers, his only painting sale had occurred over a decade earlier.

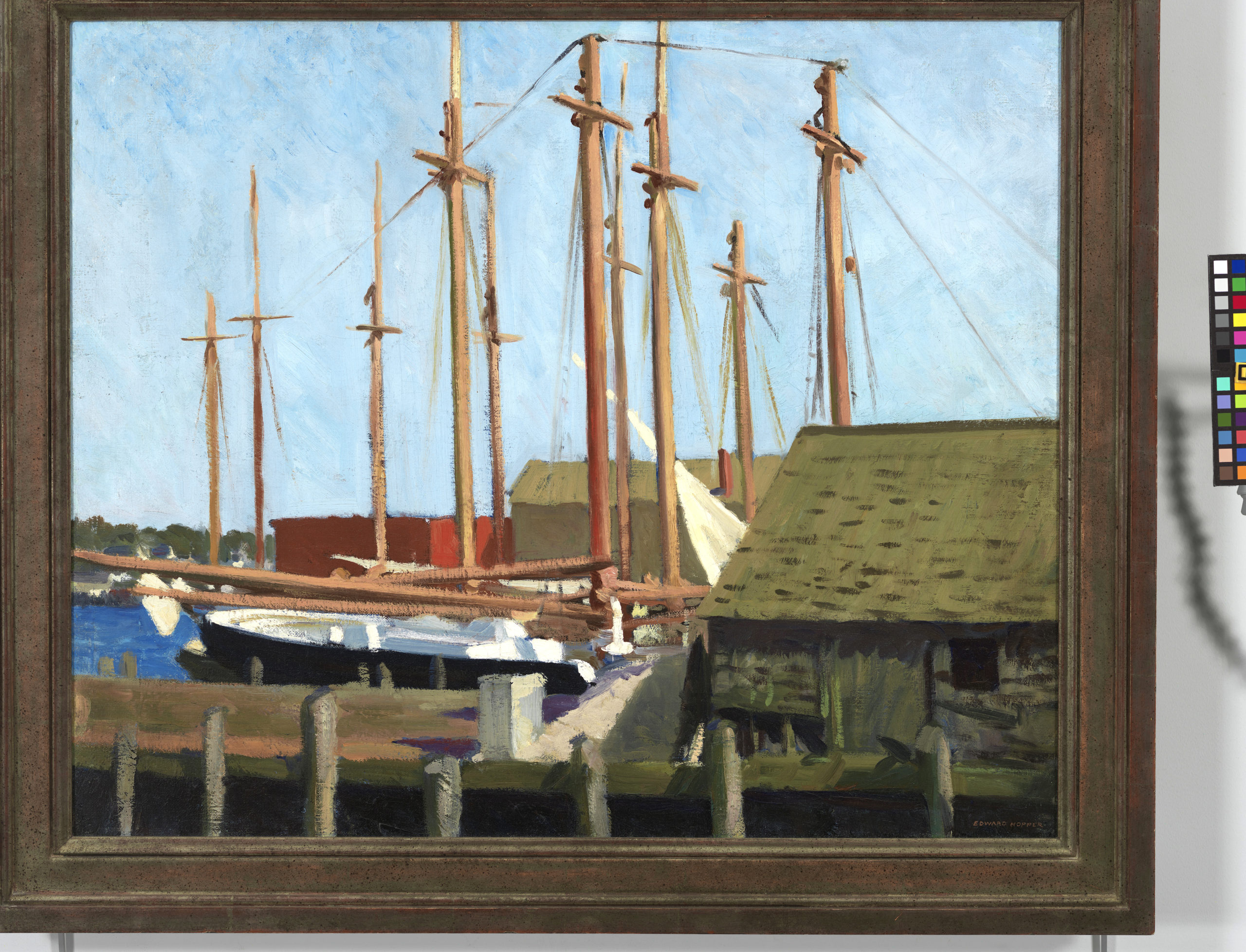

“Briar Neck, Gloucester” by Edward Hopper, 1912, oil on canvas, 24-3/16 by 29-1/8 inches (61.4 by 74 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City. Josephine N. Hopper Bequest, 70.1193. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NYC [N.B. The correct spelling of this local landmark is Brier Neck] © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYC.

Nivison came into his life as a needed life force. She was 40 and had worked for many years as an art teacher while she also pursued her dream of becoming a self-sustaining artist. Her watercolors were now being included in group exhibitions with emerging modernist masters Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Maurice Prendergast, Charles Burchfield, and Marguerite and William Zorach.

Both she and Hopper had studied at the New York School of Art under the legendary teacher, Robert Henri, and had arrived by train eager to become “sketch hunters.” Their friendship had taken off when Hopper landed on Nivison’s doorstep with her beloved cat, Arthur, who had gone AWOL, in his arms. She later credited the feline with playing matchmaker.

Nivison was also a thespian and a dancer; in many ways, the two on the surface at least were polar opposites. She was petite and always in motion; he was tall, and largely silent.

Gloucester, which is surrounded by water and severed from Cape Ann by the Annisquam River, had long attracted artists — from native son Fitz Henry Lane to Winslow Homer — and for good reason.

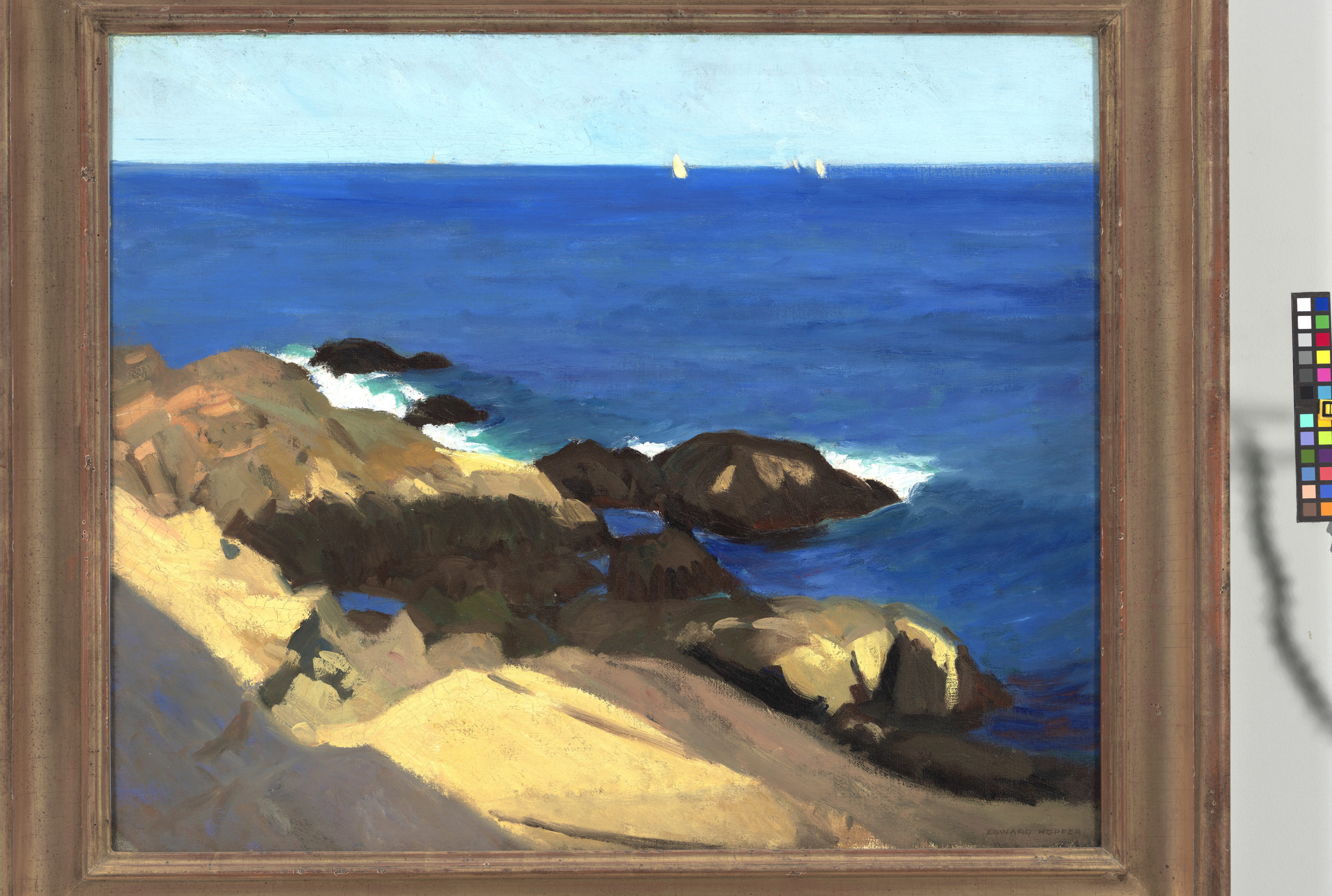

“Gloucester Beach, Bass Rocks” by Edward Hopper, 1923-1924, watercolor, 11 by 17 1/2 inches (27.9 by 44.4 cm). Private Collection. Image courtesy Christie’s. © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYC.

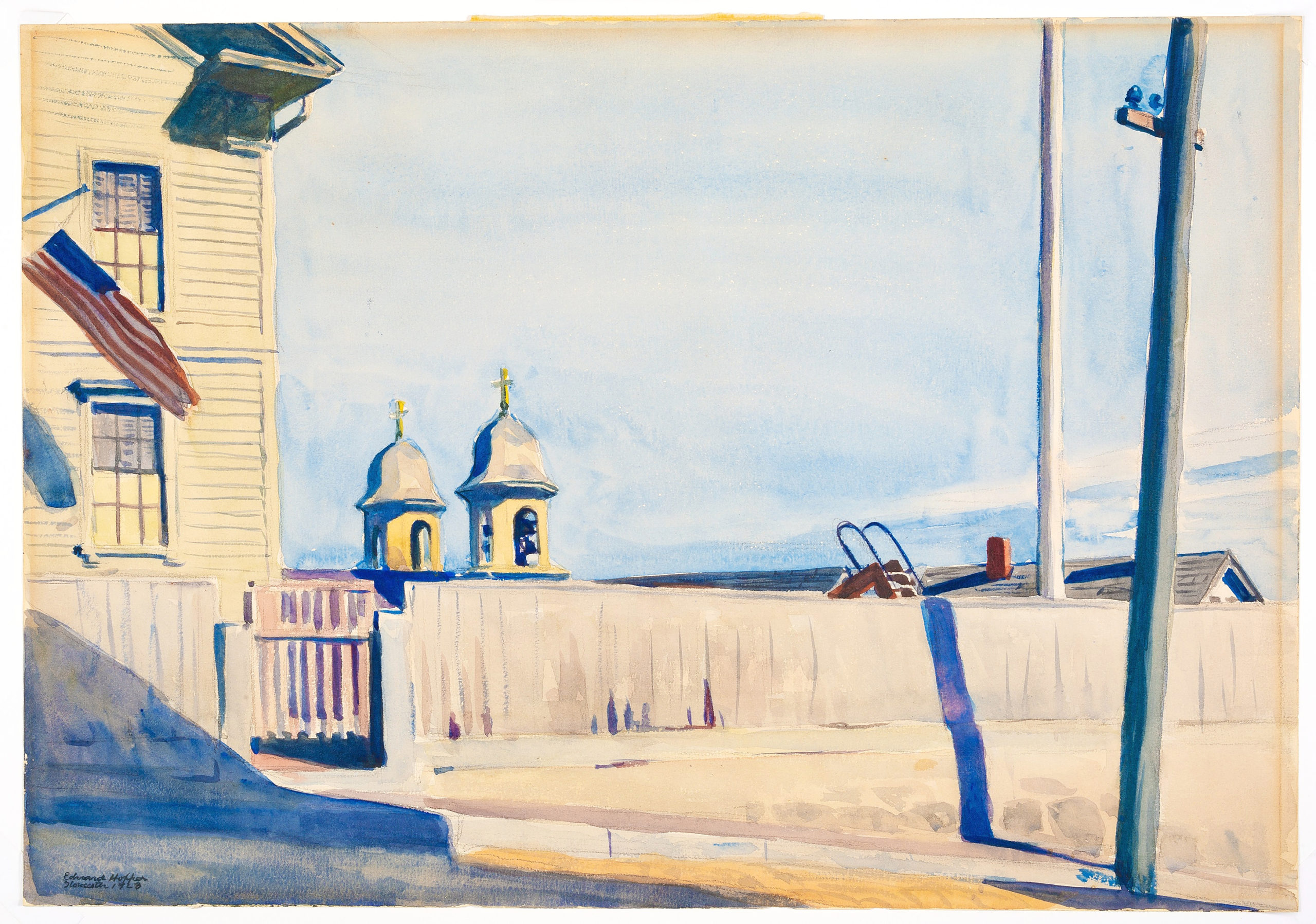

When the two embarked on painting excursions, Nivison encouraged Hopper to move from painting in oil to the more portable watercolor. The change freed him, Davis notes, and under Nivison’s skilled tutelage that summer he mastered the technicalities of the medium. In the manner of the earlier English watercolorists, he favored building up color from the lightest to the darkest washes. The method required careful planning ahead for the brightest highlights, which were created by allowing the white surface of paper to show where it was left untouched by the color washes. The end results — from “Eastern Point Light” (1923) to “Deck of a Beam Trawler” (1923); “Portuguese Church, Gloucester” (1923); “House in the Italian Quarter” (1923); “The Mansard Roof” (1923) and “Gloucester Beach, Bass Rocks” (1923) signaled that he had reached his destination. This new medium proved revelatory for the artist, who confessed with happy astonishment to his friend Guy Pene du Bois that while it had taken him “years to paint a cloud in the sky, he was suddenly learning how to paint clouds with watercolor.”

Henri, in his classic treatise, The Art Spirit, had theorized, “In all great painting of still lifes, flowers, fruit, landscape, you find the appearance of interweaving human forms, the forms we unconsciously look for.” Hopper’s paintings seemed to mirror this, whether it was the humanoid face surfacing in a humble beam trawler, or his domestic houses with their brooding windows.

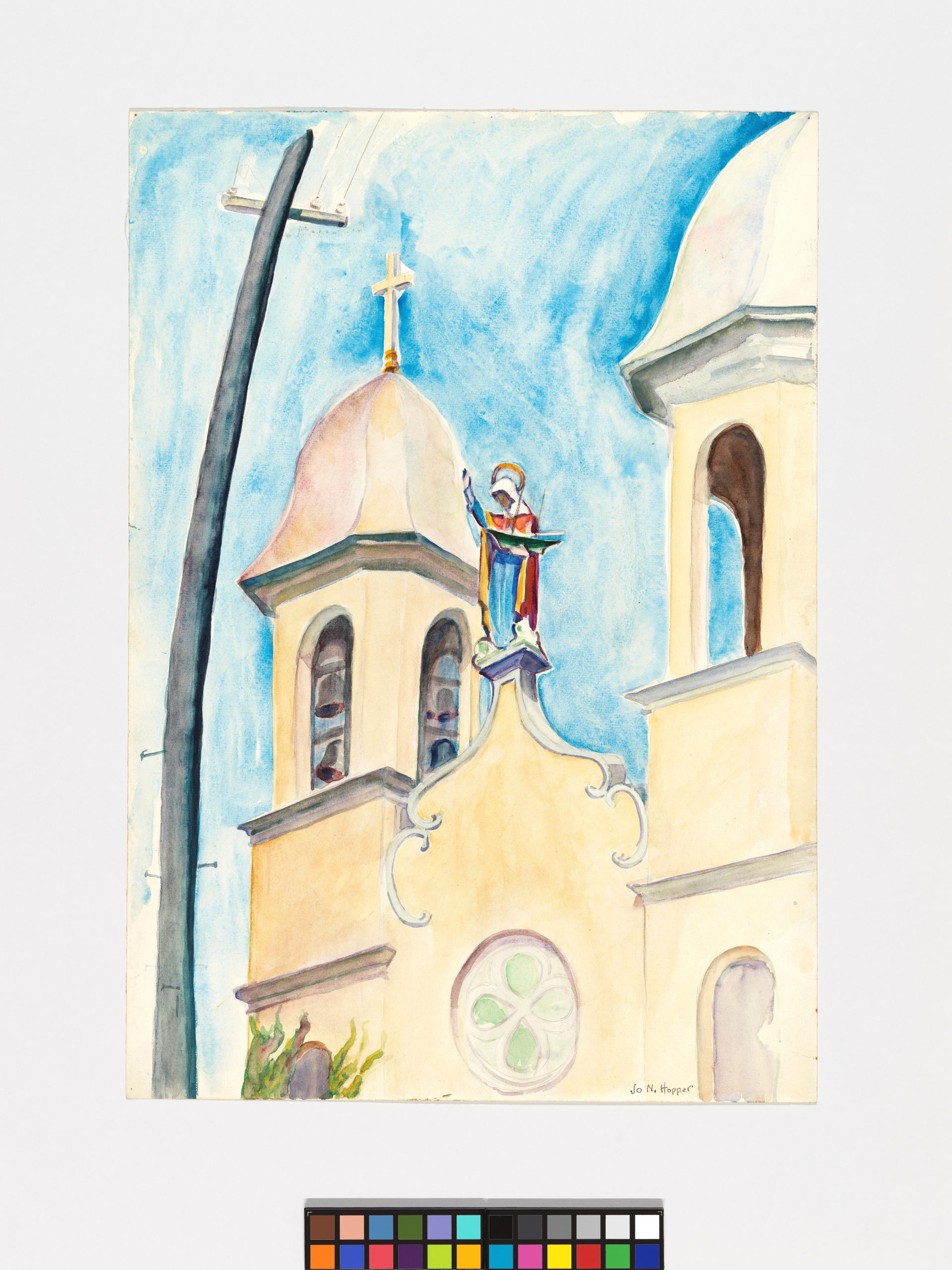

Hopper and Nivison often painted side by side, and it’s fascinating to compare where their eyes took them. As a rule, they approached their subjects from radically different vantage points. Hopper favored a horizontal orientation, and his canvases were distinct for their composed horizontal bands. She favored generally produced works with a vertical orientation, and generally opted for a brighter palette.

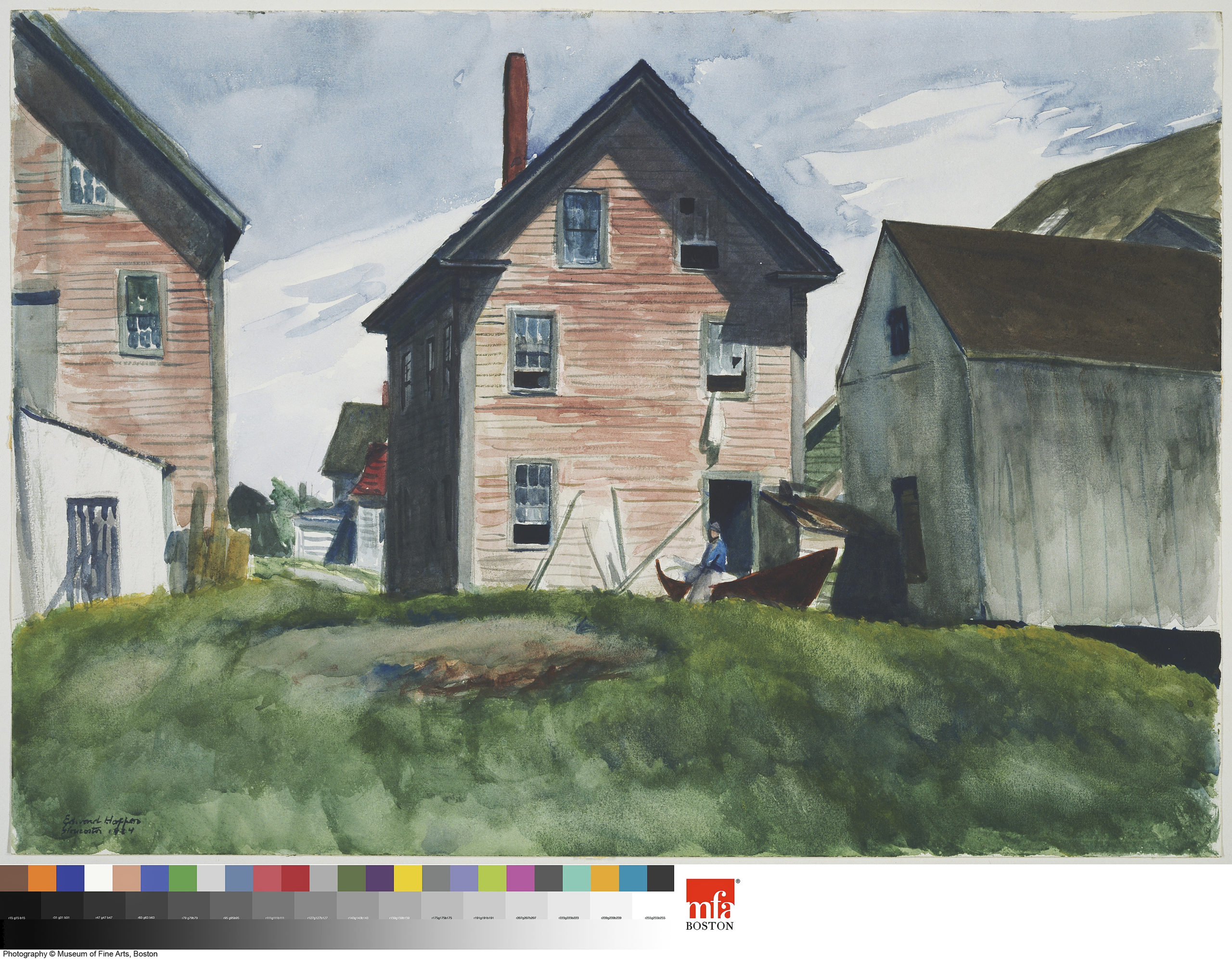

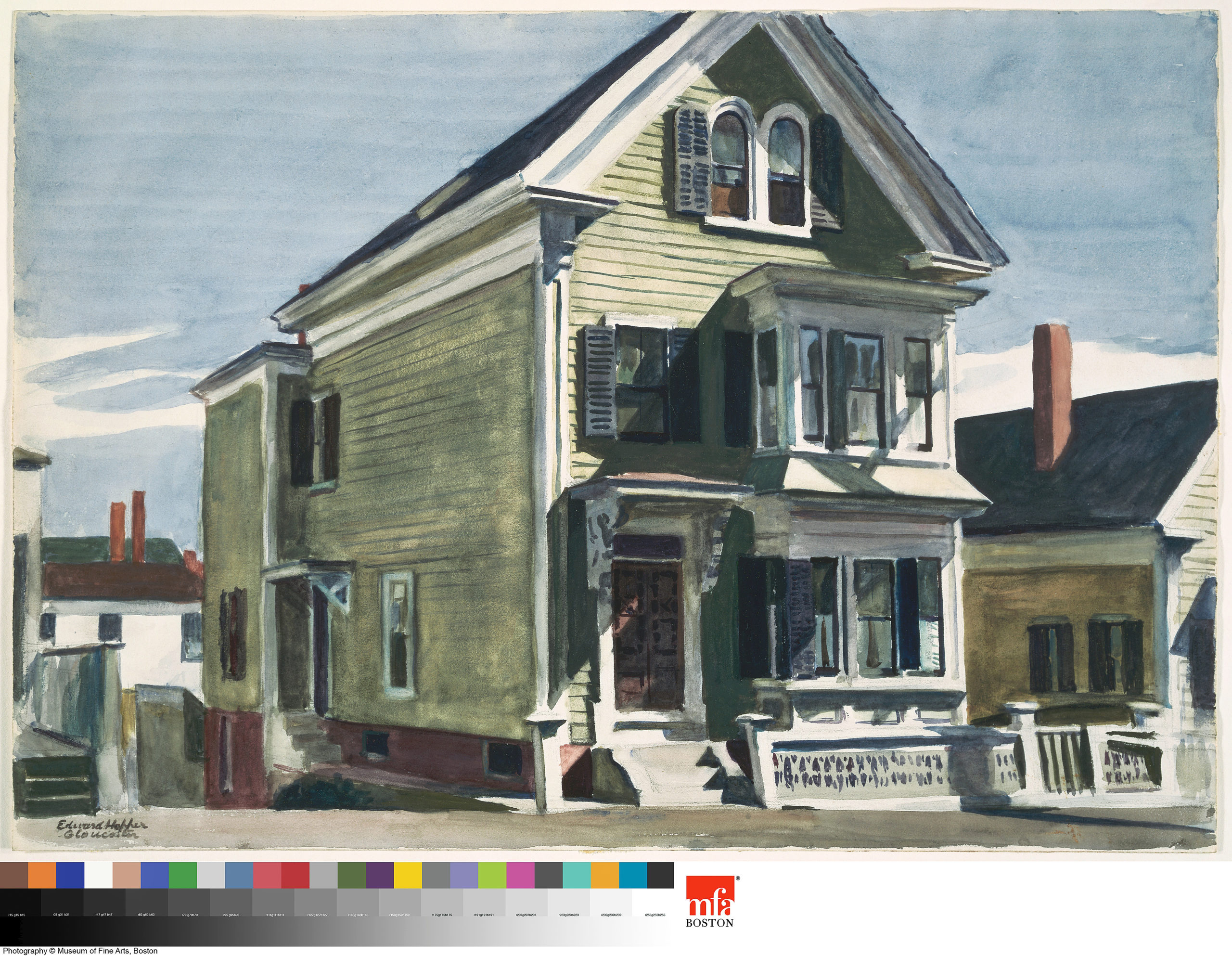

“Anderson’s House” by Edward Hopper, 1926, watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, 13-15/16 by 19-15/16 inches (35.4 by 50.7 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of John T. Spaulding, 48.720. Photograph © 2023, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYC.

Hopper was additionally drawn to the vernacular domestic architecture not unlike his childhood home in Nyack, N.Y., and to the working boats and marine apparatus that was familiar to him from his childhood on the Hudson River. As a young man he had built boats and dreamed of becoming a naval architect.

Two watercolors that survive from that summer include “Deck of a Beam Trawler” and “The Beam Trawler Seal.” Davis finds the two works a rather acquired taste — “with their dizzying array of industrial fishing equipment painted in what initially appears as a limited palette.” Upon closer inspection, though, she found herself deciphering human traits and personality in these humble working vessels, perhaps suggesting Hopper “may have been finding himself in the objects he hunted down.”

Henri had recognized Nivison’s promise and immortalized her in his now-famous portrait, “The Art Student,” which captures her clutching her brushes and wearing a paint-splattered apron. But he reserved his other accolades for Hopper’s classmates, George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. It had taken two decades of gestation, the arts critic Peter Schjeldahl writes, for Hopper to produce art that was “time-less, or perhaps time-free.” But this summer, Schjeldahl continued, Hopper had come into his own, and producing “a series of freeze-dried uncannily telling moments,” which augured what was to come.

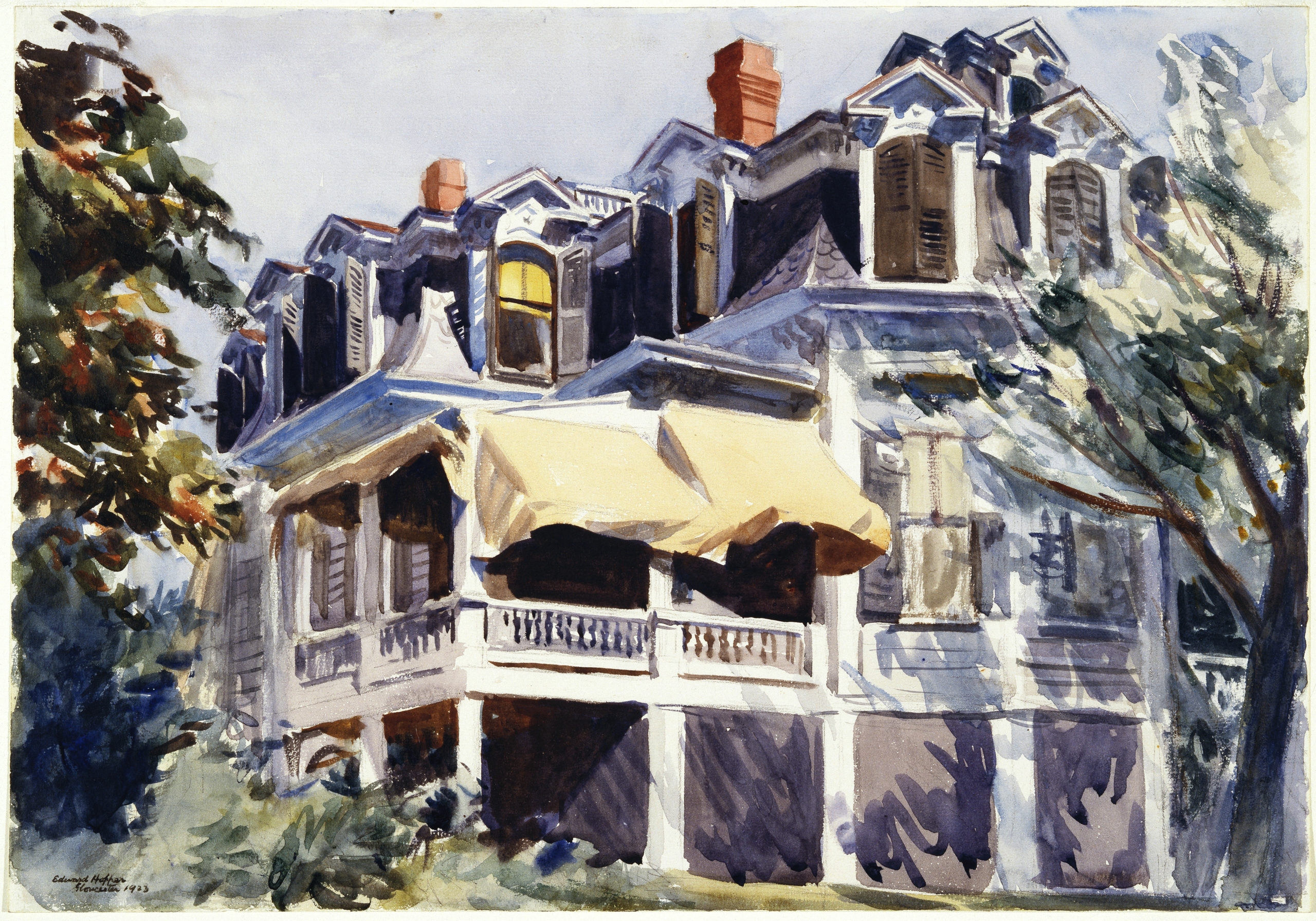

“The Mansard Roof” by Edward Hopper, 1923, watercolor over graphite on paper, 13-7/8 by 20 inches (35.2 by 50.8 cm). The Brooklyn Museum, New York City Museum Collection Fund, 23.100. © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYC.

When the summer ended and the two returned to New York, Jo took a selection of Hopper’s watercolors with her to the Brooklyn Museum and lobbied for Hopper’s work to be included alongside hers in the museum’s upcoming major biennial watercolor exhibition. The jurors took six of his Gloucester works and the museum eventually purchased “The Mansard Roof” (1923), now considered one of his finest house portraits from this period, for $100.

The two married the next year and embarked upon a 43-year partnership, with Jo assuming roles as his manager as well as his model and muse. While it had been fine, apparently, when she was a young artist to evince determination and talent, once she married, her husband’s career took precedence. And this was not only Nivison’s story, the feminist art historian Elizabeth Thompson Colleary, takes pains to note. Other women artists of the time, including Henri’s two wives and George Bellows’ wife, Emma Storey, relinquished art careers as well. Jo did continue to paint throughout her life, however, albeit relegated, for instance, to the category of “Lesser and Unknown Painters” in an exhibition at the American Express Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Colleary, who drew upon the archives at the Whitney Museum of American Art to mount a solo show for Nivison in the winter of 2022 at the Edward Hopper House Museum and Studio Center, is already at work on another exhibition, convinced that a reappraisal of Nivison as an artist is long overdue.

In subsequent trips to Gloucester in 1926 and 1928, Hopper produced several fine paintings, including “From Gloucester Beach, Bass Rocks” (1923-24); “Gloucester Mansion, Hodgkin’s House” (1928), “Anderson’s House” (1926) and “Cape Ann Granite” (1928). He returned to New York with 13 watercolors and 13 major oils, in time for what turned out to be a hugely successful exhibition at the Rehn Gallery in 1929. The show cemented his reputation as an artist whose work in oil was equal to his work as an etcher and watercolorist.

“Cape Ann Granite” by Edward Hopper, 1928, oil on canvas, 29 by 40 1/4 inches (73.5 by 102.3 cm). Private Collection. Image courtesy Christie’s. © 2023 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NYC.

Many of these works on display will be new to Cape Ann residents, and Barker promises visitors will be delighted by how fresh and alive they seem. And, because so many of his subjects can be encountered within easy walking distance of the museum on Pleasant Street, Barker’s staff has produced a map and brochure to make a visit to the museum a chance to see the sites and subjects that Hopper and Nivison painted in situ. Gloucester’s vernacular architecture moves from the simple Italian and Portuguese neighborhoods to the elegant and ornately embellished homes in the town’s wealthy enclaves. Be sure to scale the hill to the lovely Our Lady of Good Voyage Church to compare Nivison and Hopper’s versions.

Accompanying this exploration is Davis’s masterful catalog, published by Rizzoli Electra and opening the door, one suspects, to years of additional scholarship. Davis, an art historian with several award-winning publications to her name, has focused over the years of research on a number of New England artists of note, and has long been interested as a scholar in the ways in which art has been shaped by a sense of place.

Significant works have been borrowed from the Whitney Museum of Art; the Brooklyn Museum; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; National Gallery of Art; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and 28 other institutions and private lenders; There are 57 by Hopper, seven by Nivison and one by Henri.

Barker is eager for museum visitors to see them. “Happily — they’ve been properly cared for throughout the years…and there’s a freshness to them — as if they have just come off the easel.”

“Edward Hopper & Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape” is on view at the Cape Ann Museum through October 16.

The Cape Ann Museum is at 27 Pleasant Street. For more information, 978-283-0455 or www.capeannmuseum.org.