One of a pair of “precious treasures” display cabinets (detail), Yongzheng or Qianlong period, 1723–95. Lacquer with gold on wood core, metal with gilding and ivory. ©The Palace Museum.

By Kristin Nord

SALEM, MASS. – What do garments, accoutrements and the objects we surround ourselves with reflect about our status, our values and the societies we inhabit? In “Empresses of the Forbidden City, 1644-1912,” a captivating exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum, the aim has been to probe the ways in which objects made for and by women illuminate this part of the Qing imperial story.

For co-curators Daisy Yiyou Wang, the Robert N. Shapiro curator of Chinese and East Asian Art at the PEM, and Jan Stuart, the Melvin R. Seiden curator of Chinese Art at Freer|Sackler, the Smithsonian’s museums of Asian Art in Washington, DC, the show reflects a four-year labor of love, involving close collaboration with scholars at the Palace Museum in Beijing, and what amounted to a deep archival dig. The Palace Museum has loaned nearly 200 objects for this cultural exchange, which will run at PEM until February 9, and then move to the Freer|Sackler in time to mark the 40th anniversary of normalized relations between the United States and China.

Parenthetically, while the PEM show was being readied this summer, the Chinese period drama, The Story of Yanxi Palace, set during the Qing imperial period, was proving wildly popular, drawing an astonishing 18 billion streams to its Chinese streaming service. This exhibit has been enjoying a bit of that tailwind in the form of a steady stream of PEM regulars and tourists since its opening in August.

When the conquering Manchus established the Qing dynasty in 1644, they brought their own semi-nomadic traditions. From the outset, there are depictions of women hunting and riding horses on a par with men; and yet, curators Wang and Stuart observed in their catalog, “by today’s standards the restrictions imposed upon empresses in China’s last dynasty are shocking.”

During this 260-year dynastic history, they continued, “The more than two dozen empresses and numerous other women were technically ‘inalienable possessions’ of the monarch and lived within stringent codes that kept them sequestered from public view and curtailed their freedom and opportunities.”

Emperors’ wives were essentially plucked from what were deemed the premier stock available to the conquering elite. An emperor married multiple women (consorts) but only one empress, or primary wife, at a time. Women filled the ranks of an eight-tiered hierarchy that included consorts, concubines and indentured servants. Atop this chain were the Emperor’s wives, only one of whom would be named Empress. The emperor’s mother, the dowager empress, was generally responsible for selecting her son’s brides.

Fertility held the key to political advancement, a goal that was sought by secluding and concealing women. This, in turn, encouraged social networks that were overwhelmingly homosocial: men spent most of their time with other men and women spent most of their time with other women.

Yet what on the surface appeared to be a militaristic gender culture held within its strictures some room for maneuverability. A number of empresses helped shape imperial history, whether as Empress Xiaozhuang (1613-1688) escorting her young son into Beijing as it became the new dynasty’s capital in 1644, or in the final rule of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) who overturned the longstanding tradition that “women shall not rule.”

The exhibition focuses on five empresses for whom historical and visual records offered the most developed stories: Empress Xiaozhuang (1613-1688), Empress Dowager Chongqing (1693-1777), Empress Xiaoxian (1712-1748), Empress Dowager Cixi and Empress Dowager Ci’an (1837-1881). Through their personal histories the viewer is able to explore not only how they functioned within closed quarters but how they exerted themselves in politics, in industry and in religious life.

It is hard not to feel that the heavy silk satin ceremonial robes functioned as elegant restraints on physical and spiritual levels, and transformed women, in effect, into gloriously appointed vessels. The women seem all but obscured in costumes replete with auspicious signs and symbols. Cascading triple stranded pearl earrings signaled the wearer’s high standing, much as headdresses adorned with pearls, tiger’s eye stones and seven gold phoenixes proclaimed the power of the throne. The Qing imperial court, which published the most stringent and comprehensive regulations on costume in Chinese history, was all about preserving Manchu ethnic identity and fostering a well-maintained social order.

Yet this dynasty oversaw a multi-ethnic and multicultural populace, and overlapping ideas could not help but lead to hybridization as well. The “horse-hooves” on display – extraordinary concoctions in which embroidered shoes were mounted on cloth-covered wooden platforms – are a case in point. Even though the Manchus had banned the practice of foot binding, it would seem the desire to emulate the fashionable lotus-gait remained.

Platform shoes with tiger heads, the character for longevity, and bats, Guangxu period, 1875–1908. Appliqué, silk satin, platforms, wood core covered with cotton, glass beads. ©The Palace Museum.

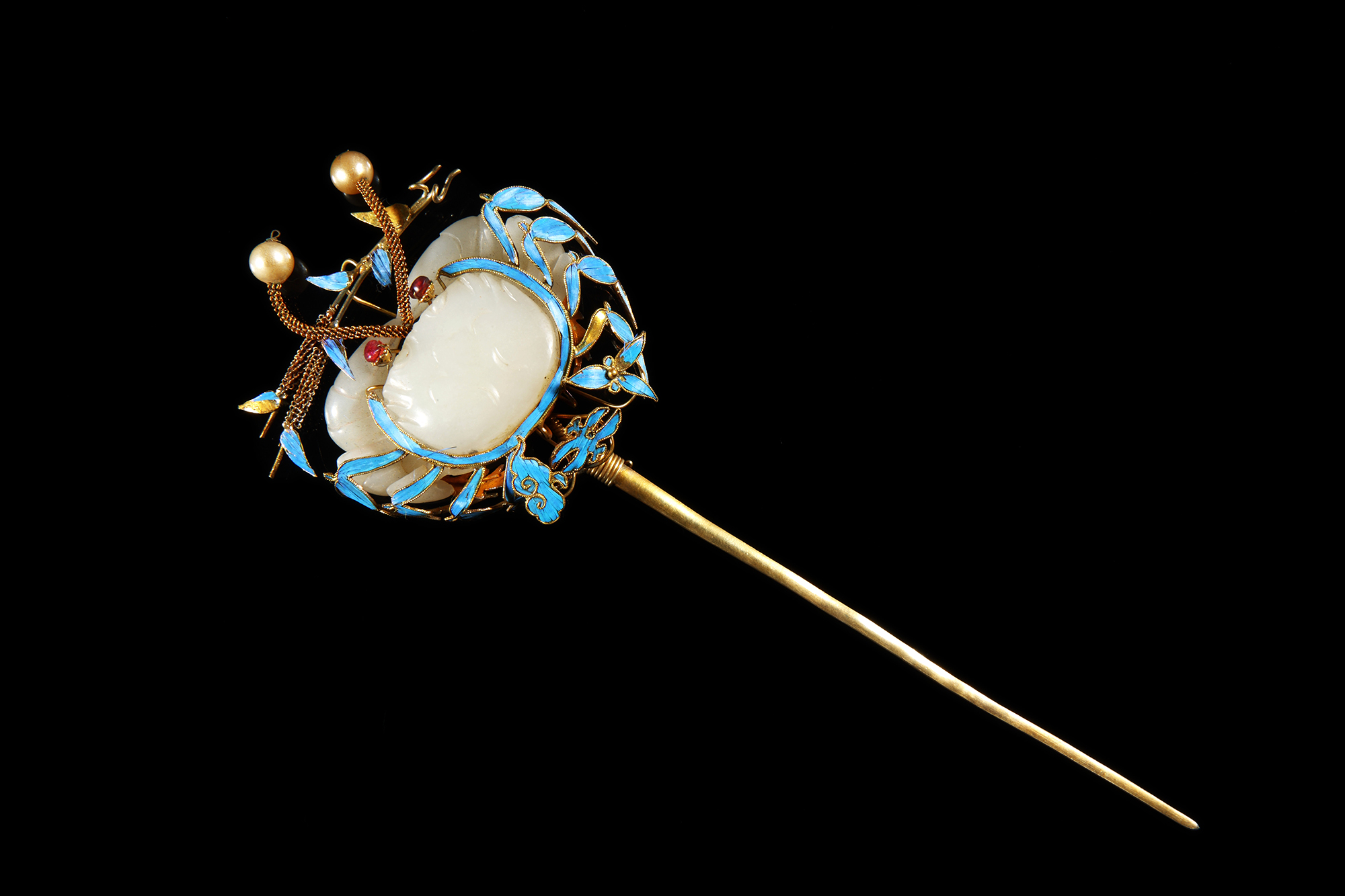

In what must have been an ominous time for the Chinese kingfisher, an array of brilliant feather jewelry was created, including bracelets and hair ornaments and headdresses called dianzi. And on display is a pair of perhaps the most elegant socks ever designed to remain undercover, their silk underbodies embellished with embroidery and wrapped in metallic and peacock-filament threads.

Curators were able to document that within their cloistered quarters, women took pleasure in fine decorative objects that were on a par with men’s. A case in point is a wine ewer, depicted in a painting commemorating Empress Dowager Chongqing’s 80th birthday celebration. It is, in many ways, exuberantly over the top – showcasing paintings in two lobed cartouches that were created with enamel pigments on metal, a technique introduced to China from Europe in the late Seventeenth Century, and then surrounded by cloisonné. It is a hallmark of the Qianlong period, when court art was revered for sumptuous and complex surface textures and technical perfection. Furthermore, research into the objects in Empress Dowager Chongqing’s quarters indicates there was no strict gender divide in room furnishings and decoration. Two matching lacquer display cases, one of which is on view, would have been used for storing books, scrolls and art, what she deemed as her treasures.

In addition to a number of sartorial gems on loan for this exhibition, there are some other bonafide masterpieces: a massive gold shrine, or stupa, commissioned to ensure the empress Dowager Chongqing’s safe transport to Buddhist paradise. Crafted of gold and silver alloy, with coral, turquoise, lapis lazuli and other semiprecious stones, and mounted on a wooden pedestal, it is a major attraction at the Palace Museum.

A Kanjur Sutra, crafted of more than 50,000 sutra leaves in gold ink on indigo paper, bookended with inlaid jewels, is another remarkable loan from Beijing. It was commissioned by Empress Dowager Xiazhuang as an expression of religious piety.

Some empresses had little or no romantic attachment to the emperor, but there was one notable exception. This was the abiding love between the Qianlong emperor, one of China’s greatest cultural patrons, and the empress Xiaoxian, whose untimely death thrust him into profound mourning. An elegy on display underscores the depth of his sorrow.

Seal of empress with double-headed dragon with box, tray, lock, key and plaques, Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Republican period, 1922. Gold alloy with silk tassels. ©The Palace Museum.

While one might imagine the court itself had more than enough material to generate its own internal drama, it did not dampen the appetites of some Qing women, the Empresses Dowager Chongqing and Cixi in particular, for court theatre. It was Cixi who spirited a revival by commissioning at the end of the Nineteenth Century a series of plays about a family of courageous and talented women who broke from traditional domestic roles to act as warriors during a time of crisis. The story line, interestingly, mirrored that of Cixi’s.

When empresses and empress dowagers died, their full-body portraits were venerated in a private ancestral viewing hall that was restricted to members of the imperial family. These works were unsigned, and seen as “Spirit vehicles” that would encourage in worshippers “a personal, emotional experience,” Stuart writes. By the beginning of the Twentieth Century, as this final empress dowager embraced modernity, she stepped out from the shadows. According to Ying-Chen Peng, who contributed to the catalog’s essay on Empresses and Qing Court Politics, Cixi turned to photography “as a means by which to model perceptions of her character at the very moment photography was becoming a mass-media vehicle and the Qing dynasty was struggling to survive in a hostile imperialistic world.”

In just a few years, “China’s last dynasty would be replaced by the Republic of China,” she wrote. “In the next decades, women in China would step out of the inner quarters and participate in politics as individuals rather than as annexes to men who wielded authority in the name of filial piety.”

The PEM has the oldest and one of the finest Asian departments in the United States, and in recent years it has burnished its reputation as a go-to resource for Qing-related scholarship. In the early 2000s it acquired a 200-year-old Qing merchant house, the only example of an entire Chinese vernacular building on display in the United States. A 2011 PEM/Palace Museum acclaimed collaboration, “The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City,” drew a half-million visitors. With “Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644-1912,” both the PEM and the Freer|Sackler will be building upon impressive foundations.

Sadly, by agreement, the PEM is already rotating some of these precious objects on loan, a reminder that this extraordinary exchange is temporary. Given our current relations with China, these major works may not come our way again for quite some time.

In summary: “Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644-1912” continues at the Peabody Essex Museum, 161 Essex Street, through February 9. For additional information, 978-745-9500 or www.pem.org.