The River Walk, one of four marked path comprising Florence Griswold Museum’s Artists’ Trail, leads visitors along the Lieutenant River, where American Impressionist painters set up their easels. Photo Ian Dobbins, courtesy Florence Griswold Museum.

By Laura Beach

STOCKBRIDGE, MASS. – Largely overshadowed by the visible frustration and fatigue of the past few months, creativity is on the rise. With everything from the museum blockbuster to the summer vacation season effectively upended, we are reassessing our engagement with the material world, countering our mass exodus from the public sphere with a forceful embrace of home. What is it and what is it for? Where does professional life end and private life begin when the boundaries between work and repose dissolve? In devising imaginative ways to accomplish the workaday, new templates for living are superseding the old.

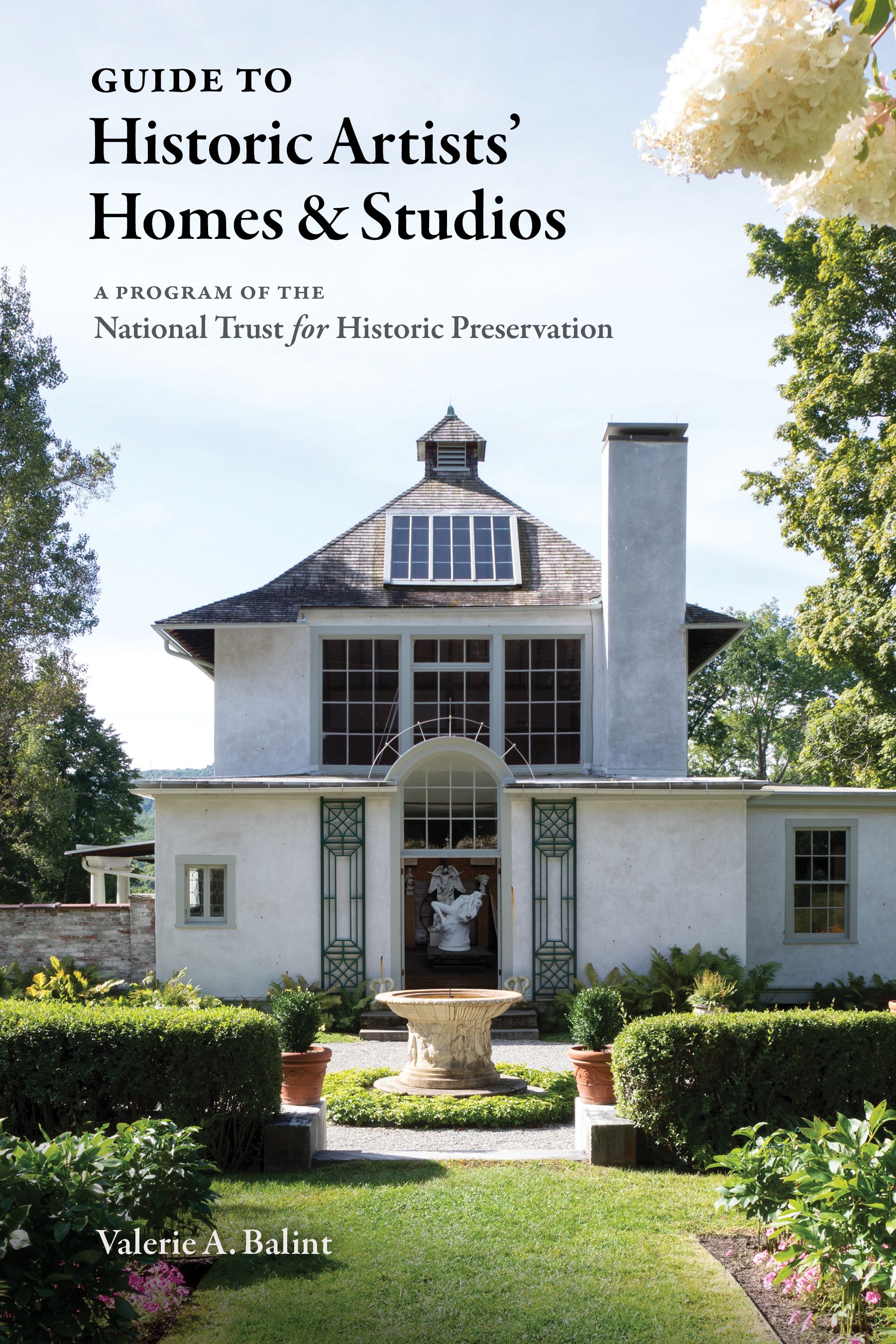

Members of the creative classes, artists especially, have long fused professional endeavor with private expression in ways that resonate now. Their inspirational efforts are told in the new Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios. The portable volume written by Valerie A. Balint and published by Princeton Architectural Press in June is a Baedeker for the summer road trip in a season when recreational travel, if at all, will largely be by car. Here readers starved for aesthetic nourishment will find 44 destinations, each unique, all exceptional. Many maintain distancing-friendly grounds for strolling and sketching; most are in the early stages of reopening their interiors on a limited basis. Nearly all are ramping up new content on their websites, easily explored through the collective portal www.artistshomes.org.

Keenly interested in creativity as manifested in the built environment, Balint – who earned a degree in public history and once oversaw the New York effort of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s national “Save Outdoor Sculpture!” program – worked at Olana, the Orientalist fantasy created by Hudson River School painter Frederic Church (1826-1900), and at the restrained, Bauhaus-inspired refuge of Modernists George L.K. Morris (1905-1975) and Suzy Frelinghuysen (1911-1988), both houses part of the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS) consortium. As manager of the HAHS program, Balint’s current base in Stockbridge is Chesterwood, the former summer retreat of Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), whose statue of Lincoln may be the best known example of American art.

The property, which Balint first encountered on a school visit years ago, changed the curator’s life, ultimately setting her on her present career path. The visit, Balint recalls, “was an incredibly powerful experience for a young person. The ‘Lincoln’ we know from the nation’s capital is mythic in scale, but it has transcended even that. It is part of our collective conscious, an element of our national visual vocabulary. Here at Chesterwood, French’s working model of Lincoln, small by comparison with the completed sculpture, is still fairly large, yet the studio space is intimate. You are conscious of the figure having been made by a person. It’s a revelation.”

Wanda Corn’s passion for artists’ houses dates to the 1960s, when the art historian first visited Cézanne’s studio in Aix-en-Provence. Corn was a driving force in the creation of HAHS, launched by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1999. “I found myself breathless standing alone in an intimate space where so much hard work and innovation had transpired,” Corn writes of the French landmark, recalling the “ordinariness” of the studio props and the “humility” of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the rock formation whose identity Cézanne transformed. “It was Cézanne’s high-level conversation with its folds and irregular contours that had given the peak its contemporary grandeur,” she observes, concluding, “‘Place’ is not a timeless absolute; it is a constructed identity, and artists are often the ones who produce visual representations defining particular topographical spaces.”

George L.K. Morris Studio, at the home he shared with his wife, painter Suzy Frelinghuysen. Photograph by Geoffrey Gross, courtesy of Frelinghuysen Morris House and Studio, Lenox, Mass.

Scattered across 21 states, HAHS properties, all open to the public, collectively draw more than a million visitors a year. Only Chesterwood, whose grounds will be open for self-touring with advance registration, belongs to the National Trust; the rest operate as assorted public and private entities. HAHS members share advice and resources. The Henry Luce Foundation and the Wyeth Foundation for American Art underwrote much of the expense of the new guide, begun in earnest after Balint relocated from Olana to Chesterwood, the latter directed for the past dozen years by scholar Donna Hassler, a champion of the book project.

Appealing in their variety, the sites reflect diverse artistic traditions and concerns. As Corn notes, some “tell stories of a single artist, some of artist-couples, some of artist colonies and some of generations of artists who worked in the same space.” Among the least expected, Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches, La., preserves the legacy of Cammie Henry, who collected historic log cabins and created a haven for artists and craftspeople, among them Clementine Hunter (circa 1887-1988). The understated Boise, Idaho, home of another self-taught artist, James Castle (1899-1977), offers proof that genius is limited by neither modest means nor meager materials.

The study collection formed by Roger Brown (1941-1997), an Alabama-born member of the Chicago Imagists, houses a lively array of folk and self-taught art likely to appeal to Americana enthusiasts. The studio of Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) still surges with the energy of his once radical drip paintings. Craft afficionados will sense the spirits of woodworkers Wharton Esherick (1887-1970) and Sam Maloof (1916-2009), who built and furnished distinctive houses, both now HAHS sites.

Made famous by the sculptor Donald Judd (1928-1994), who used the landscape as a canvas for his environmental installations, the Texas outpost Marfa is a contemporary artists’ colony of international renown and a popular tourist destination. The most personal of Marfa’s spaces, writes Balint, is La Mansana de Chinati, the compound where Judd lived and worked. Judd’s personal collection of fine and decorative arts, including furniture he designed himself and his early paintings from the 1950s and 1960s, are scattered about the property.

With more sites already in the nomination process, HAHS is likely to grow more diverse in coming years. In a nod to the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States, the group is turning its attention to women artists. It hopes to include more vernacular environments, as well as more spaces relevant to African American and Latinx artists. Its remit is growing beyond the mid-Twentieth Century.

View of Wharton Esherick’s home and studio from the west. Photo by Charles Uniatowski, courtesy the Wharton Esherick Museum, Malvern, Penn.

For experiencing what Wanda Corn calls “moments of recognition” – satisfying encounters with physical inspirations for works of art – no place is more rewarding than the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Conn., home to the recently opened Robert F. Schumann Artists’ Trail. Four self-guided walks lead visitors to spots depicted in paintings by the American Impressionists who summered in the area. Organized by Florence Griswold Museum curator Amy Kurtz Lansing, the related exhibition “Fresh Fields” highlights new acquisitions and offers the latest findings from research underpinning work on the Artists’ Trail. The museum reopens to members July 1 and the public on July 7, with limited admission and by 24-hour advance ticketing only.

In Catskill, N.Y., the grounds are open from dawn to dusk at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, where visitors can view the Catskill Mountains as the painter did, from his porch. A digital guide to the site is posted on the institution’s website.

For armchair travelers, a camera broadcasts images online from the Winslow Homer Studio in Prouts Neck, Maine, offering live views of the crashing surf and rocky shore that absorbed the artist. Likewise, feed from the Olana Eye Skycam delivers the panoramic Hudson River Valley view that captivated Frederic Church.

The context of creation and the personal biography it entails has been a matter of public fascination since at least 1550, when Giorgio Vasari published Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Heavily illustrated with portraits of the featured artists and examples of their work, the Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios makes such context all the more tangible.

Like many pandemic-era authors, Balint is promoting her new book via Zoom-hosted lectures. When we spoke, she was planning a June 22 talk to be hosted by Philip Johnson’s Glass House, a National Trust for Historic Preservation site though not part of the HAHS consortium. On July 10, she will discuss HAHS’s nationally touring exhibition “Preserving Creative Spaces,” mounted but subsequently “dark,” in the current parlance, at the Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts in Alta Loma, Calif.

-1024x682.jpg)

View across the lake to the Main House, Frederic Edwin Church’s Olana, Hudson, N.Y., 2010, ©Peter Aaron/OTTO.

“My hope is that the short profiles contained in the book will encourage readers to seek out these special places,” Balint writes, adding, “In all their varied expression, these properties are fragile and irreplaceable and require champions to ensure their future. May this guidebook begin your own journey of discovery to the abundant riches these sites have to offer.”

For more on Historic Artists’ Houses and Studios, visit the program’s website at www.artistshomes.org. The site includes information about each property, plus links to their individual websites, where specifics on current hours and programming can be accessed.

Autographed copies of the Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios may be purchased online from the shop at Chesterwood.org. The volume is also for sale at Bookshop.org and Indiebound.org. Proceeds benefit Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios.

.jpg)

.jpg)