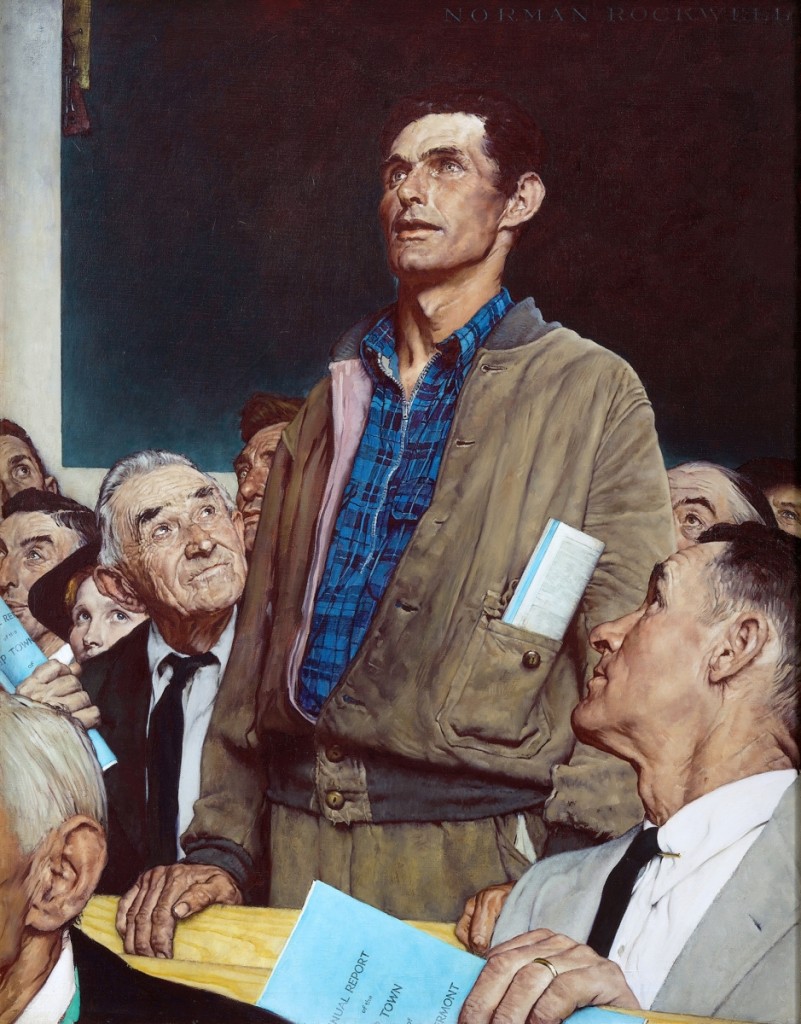

“Freedom of Speech” by Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), 1943. Oil on canvas, 45¾ by 35½ inches. Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 20, 1943. Collection of Norman Rockwell Museum. ©SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, Ind. All rights reserved.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

WASHINGTON, DC – “The Four Freedoms” is among American painter Norman Rockwell’s most popular works. First published in the widely circulated Saturday Evening Post in 1943, and then distributed even more broadly by the US government in a national tour and a set of posters promoting the sale of war bonds, the four images have lingered in individual homes and in the collective memory ever since. So near-universal is their appeal that it is surprising to learn that they are, to a great extent, about the merit of unpopular ideas.

The series was created in support of a challenging idea that was struggling to find traction in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s America, and it was inspired by a moment the artist witnessed, in which a local man took the floor at a town meeting to speak against the crowd. In the painting inspired by that moment, “Freedom of Speech,” we see the man capture the attention of the others in the room, who while they might not agree with or even fully understand the man’s point of view, respectfully listen nevertheless. “The Four Freedoms” series did much the same thing during wartime America, giving a troubled country an opportunity to listen to a common narrative and coalesce around a shared sense of identity and purpose. The complexities of that identity and purpose are explored in “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms,” organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum and traveling to at least six venues through the fall of 2020. It is on view at the George Washington University Museum and the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, February 9 through May 6.

Exhibition co-curator James Kimble of Seton Hall University outlines in his catalog essay the evolution of Roosevelt’s concept of the four freedoms and how it found expression in Rockwell’s work. In 1940, when the world was at war but the United States was deeply divided over whether or not it should get involved, Roosevelt spoke to a group of young people about “the elimination of four fears,” related to instability and loss of freedom during wartime. The president continued to hone this concept during his reelection campaign, eventually focusing on the freedoms themselves rather than the fears of losing them: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from fear and freedom from want. With his third term won and with war looming, Kimble writes, he lobbied to include the four freedoms in the Atlantic Charter and set the US Office of Facts and Figures to work drafting a public pamphlet on the theme.

“Freedom from Want” by Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), 1943. Oil on canvas, 45¾ by 35½ inches. Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 6, 1943. Collection of Norman Rockwell Museum. ©SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, Ind. All rights reserved.

Kimble is careful to point out that Roosevelt did not invent the four freedoms – artists, writers and military figures had used the same or similar concepts in the past to promote democratic ideals internationally. The president’s innovation, instead, was to tailor the freedoms to Americans as they struggled to break the surface for air after the Great Depression and before the inevitable deprivations of war. Roosevelt’s objective was to give Americans ideals to focus on and nurture during those dark years, to create a vision of a postwar world in which all Americans, and all the world, could share in the promised freedoms.

All but the habitually cynical are likely to agree today on the enduring power of that ideal; however, it was a surprisingly hard sell at the time. Those who were not fans of Roosevelt’s policies saw the four freedoms either as a bid to foster dependence on government and promote a welfare state or as a transparent effort to sway public opinion toward entering the war. For others, Roosevelt’s four freedoms simply did not register as anything particularly new or meaningful. Still others, even after the war had begun, scoffed at the idea of numerically quantifying the cherished concept of freedom. “Patrick Henry did not ask for Nos. 1 to 4, nor for Nos. 3, 5, 7 and 9,” Time magazine observed acidly. “He simply used the singular.”

Norman Rockwell was not among those people. Already hard at work on projects to support the US War effort – 1942s “Let’s Give Him Enough and on Time” was commissioned by the Army’s Ordnance Corps – Rockwell strove to be of further service and was drawn to the idea of the four freedoms as the basis for a series. His “creative breakthrough,” writes Kimble, came from the memory of a town hall meeting in Arlington, Vt., during which his next-door neighbor rose to express an unpopular opinion. “The memory gave Rockwell a sudden jolt,” Kimball wrote. What better to illustrate freedom of speech than this moment when a man, utterly alone in his opinion, is nevertheless free to take the floor and is treated with respect?

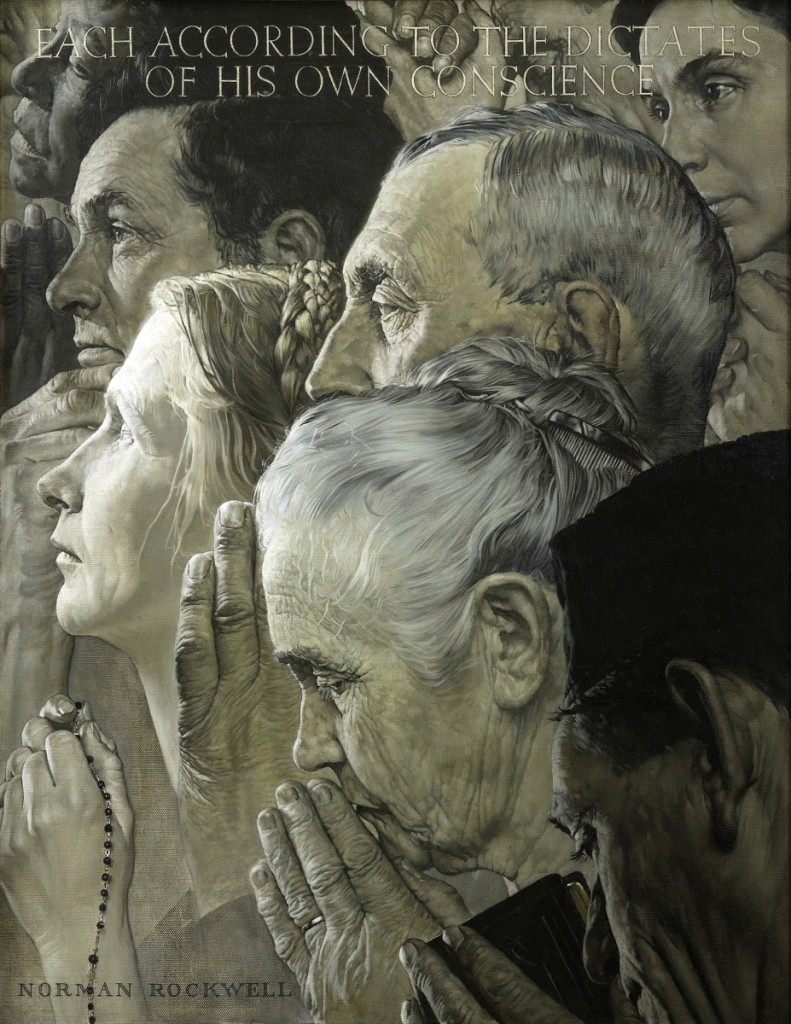

“Freedom of Worship” by Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), 1943. Oil on canvas, 46 by 35½ inches. Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, February 27, 1943. Collection of Norman Rockwell Museum. ©SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, Ind. All rights reserved.

From this moment of inspiration, the other paintings in the series rapidly took shape. In all four, a single male figure rises as the anchor of the composition, functioning as a kind of archetype of Everyman leadership. “Freedom of Speech:” the central figure, dressed in work clothes, stands proud and speaks his piece among his better-dressed neighbors. “Freedom from Want:” a kindly patriarch presides over a family table laden with a Thanksgiving feast. “Freedom from Fear:” a father watches as his wife tucks in two peacefully sleeping children; clutched in his hand is a newspaper in which the words “bombings,” “horror,” and “hit” are prominent in the headline. “Freedom of Worship:” a series of heads and praying hands are seen in profile and semi-profile; a central male head is larger and taller than the others, almost touching the bottom of the inscription along the top of the canvas: “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.”

There are complexities for the modern viewer to unpack here, certainly. But for the moment in which these paintings were produced and published, they were successful in speaking to as large a swath of the American population as any work of fine art had before or since. Part of that success lay in Rockwell’s decision not to show the horrors of lost freedoms-imprisoned dissenters, starving families, violence on the streets – but to show the freedoms themselves. “Rockwell’s was clearly a new style of propaganda,” writes Stéphane Grimaldi, chief executive officer of the Mémorial de Caen in Normandy, where the exhibition will travel next. “Rockwell never gives up his fundamental choice of telling without hurting.”

“The battle is very distant from these images,” said Kimble in a recent conversation. “Even in Freedom From Fear, the headline is about as close as we get to the actual war…[the] focus is about home and the family.” In this, Kimble argues, Rockwell “changed what the meaning of the four freedoms was.” By sublimating the horrors of war – which, to be fair, he depicted less obliquely in other works, including “Give Him Enough” – Rockwell also created works that people could pin up on their walls just as they did portraits of George Washington and reproductions of Leonardo’s “Last Supper.” And that was just what many did, adding “The Four Freedoms” to a small canon of works that represented hard-fought, unimpeachable values – things upon which all good people could agree.

“Freedom from Fear” by Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), 1943. Oil on canvas, 45¾ by 35½ inches. Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, March 13, 1943. Collection of Norman Rockwell Museum. ©SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, Ind. All rights reserved.

Rockwell’s use of working-class Americans as subjects and models was also something of a radical innovation in the fine arts (the abstracted, heroized workers of the social realists notwithstanding). Even so, there are gaps in his universalized depiction of America that modern scholars have often remarked upon. It is difficult for Twenty-First Century viewers to ignore the fact that three of the four paintings include only white people. Even “Freedom of Worship,” while it may well have been daring for its day – Kimble says that in that context it was “pretty darn inclusive” – in the end relies primarily on non-specificity. There are only hints of non-white Protestant traditions: the figure of an African American woman in the deep background, clutched beads that might or might not belong to a rosary, and the suggestion of a taqiyah on the nearly invisible man in the lower right. Contrast this composition with his later “Golden Rule” of 1961, for instance, a much broader depiction of a diverse and tolerant world, with a multiplicity of religious traditions represented.

The series received some criticism in its day, too. Kimble, discussing how international viewers in Allied and occupied countries would also have had access to the four freedoms concept and Rockwell’s illustrations of it, observed that “Freedom From Want,” in particular, “really wasn’t suitable for our European allies, given what they were going through…starvation was more the order of the day than a feast.” Of course, many Americans, too, could only have dreamed of a feast like this in the 1940s. Families who had made do with little or even faced starvation through a decade of economic depression were now jealously guarding their war rations of milk, meat, sugar and butter. And yet, as D.B. Dowd of Washington University in St Louis writes for the catalog, the feast itself – which seems frankly sparse apart from the turkey – is not really the subject of this painting. The eye instead is drawn, in Dowd’s words, to the “airy blanket of white light” that “suffuses everything, conferring grace on the gathering.” The painting and the series as a whole, again, strove to cast a light in the darkness, to help Americans collectively imagine an ideal future in which such basic blessings were once again the norm rather than the exception.

But now we are back to the idea of whiteness as an underlying theme of “The Four Freedoms.” To some extent, Kimble says, this is explained by the fact that Rockwell’s lifelong practice was to use his neighbors as models, and Vermont in the 1940s, as today, did not have the racial diversity of many other places. There was also pressure from the Post, which had a policy that African Americans could only appear on the cover if they were in a position of servitude. “I like to think that there’s some pretty good evidence that [Rockwell] himself was progressive and that he struggled against restrictions placed on him by the publications that he worked for,” says Kimble. “I definitely believe that he would have had different covers and that “The Four Freedoms” themselves might have been much more inclusive had he had a different canvas than the Post to work with.”

This is more than wishful thinking, for we know that Rockwell did go on to create works like “The Problem We All Live With” (1963) and “Murder in Mississippi” (1965), which unflinchingly deal with America’s Civil Rights crisis. But apart from “The Golden Rule,” which most agree was something of a revisioning of “Freedom of Worship,” Rockwell never did reconceptualize “The Four Freedoms.” Instead, contemporary artists have taken up that challenge; a final gallery brings many of those works together in a juried exhibition created to accompany “Enduring Ideals.” Although the “Four Freedoms” initiative of artist-photographers Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur, which gained significant traction as a social-media campaign to encourage voting in the 2018 midterms, is not represented here, there are many works that similarly reimagine Rockwell’s compositions with a more diverse cast of characters and a bolder take on the issues that characterize our times. As a single example, “Freedom from What?” by Berkshire artist Pops Peterson offers a revisioning of “Freedom from Fear,” with several key changes: the family is African American; the newspaper headline reads “I Can’t Breathe;” and their expressions are not ones of peace and repose but vigilance and alarm, as they turn their heads toward some unseen disturbance.

Such revisions may not be popular with all viewers, but then again, that is never what “The Four Freedoms” were about. In the end, the series rests on the truth that even unpopular ideas are important; that, in fact, unpopular ideas – and our ability to express and hear and expand upon them – are essential to the freedoms that we cherish.

The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum are at 701 21st Street. For information, 202-994-5200 or https://museum.gwu.edu.