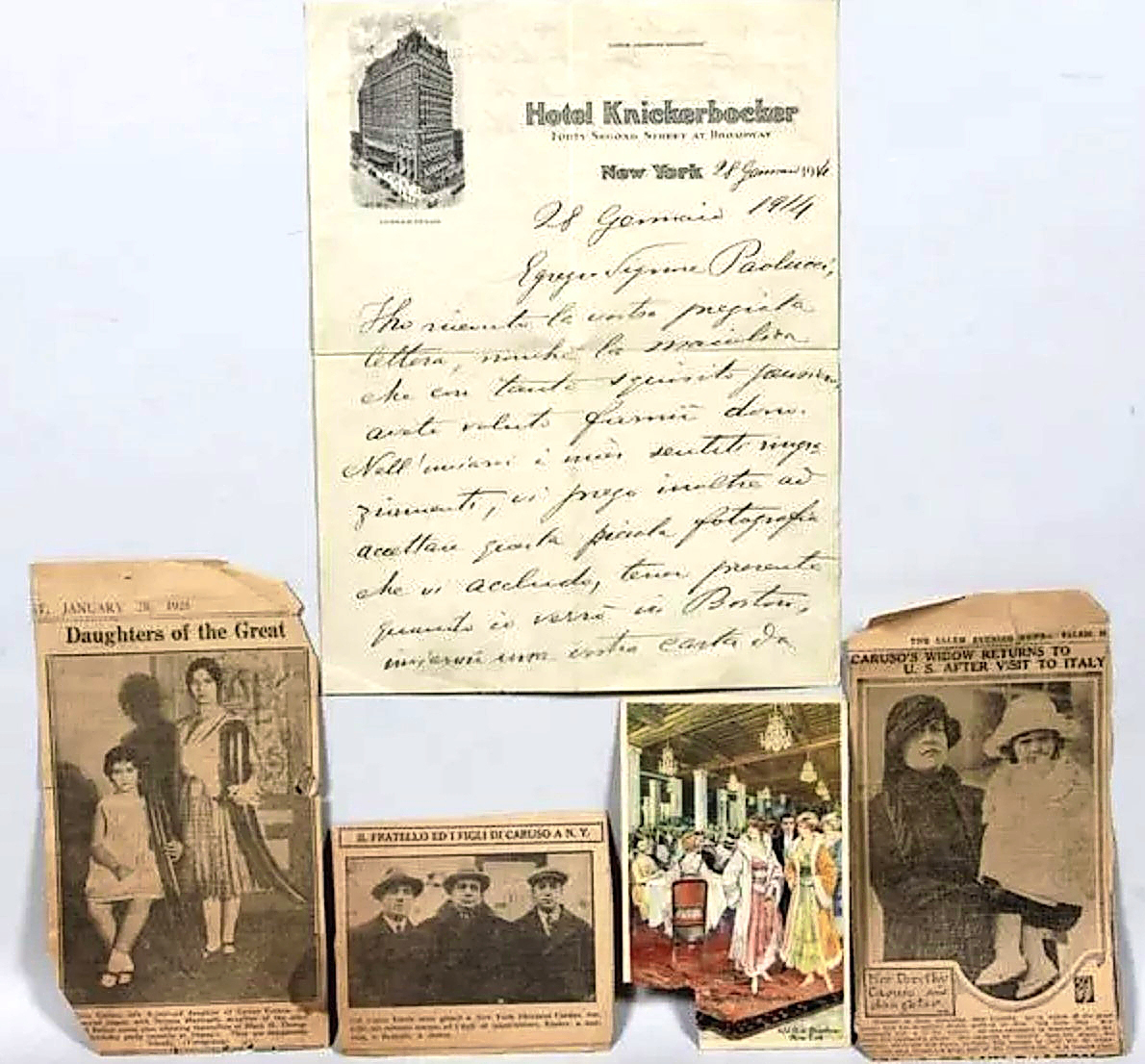

Paperwork found in a local Peabody, Mass., area estate, which includes a letter written by a man named Enrico Caruso and addressed to Luigi Paolucci in Italian regarding imported pottery, presumably from Italy, dated January 28, 1914. The paperwork also includes a postcard addressed to Luigi from the Hotel Knickerbocker in New York City, dated March 1918. This information may indicate that the Paoluccis may have also been selling imported Italian pottery in the Salem and Peabody area before 1920. Courtesy Kaminski Auctions.

By Justin W. Thomas

NEWBURYPORT, MASS. — The second book in my New England pottery book series, The Moses B. Paige Company: The Last of the Peabody Potteries (published by Historic Beverly, 2020), told the story of Moses Paige (1847/48-1941), who was born in Weare, N.H., before he moved to Winthrop, Maine, for school, around the age of ten. Once he reached adulthood, Paige became a farmer and relocated to Peabody (formerly South Danvers), Mass., about 1872. His career path quickly changed and he was soon employed at Joseph Reed’s (1809-1884) Pottery in Peabody, the former location of the longstanding Osborn family pottery, which dates back to about 1736.

Paige eventually purchased the business in 1876, where he quickly enlarged the pottery’s facilities to maximize production. By 1906, the company was incorporated and Paige served as president and general manager of the lucrative business, which specialized in household red earthenware for utilitarian and decorative needs, while also employing a small group of accomplished and talented potters. The company also sold a variety of other household wares made by manufacturers elsewhere in America.

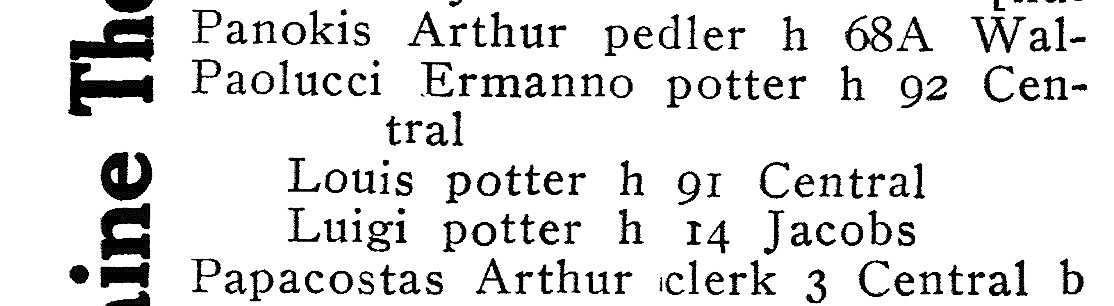

Today, it is less well known that this group of potters included two Italian immigrant potters named Ermano and Luigi Paolucci, who arrived in Salem, Mass., in 1898. Records indicate that they were working for Paige by the 1920s, although there is evidence that they were employed in Peabody as potters as early as 1915, based on information published in that year’s Peabody City Directory.

Twentieth Century red earthenware pitcher with its original lid that is described by the Peabody Historical Society, Massachusetts, as “Made at Paige Pottery circa 1930 turned by John Donovan Glazed by Luigi Paolucci Black mat-glaze.” Courtesy: Peabody Historical Society.

The directory cites Ermano as a potter working at 92 Central Street and Luigi as a potter at 91 Central Street. Central Street is where the Osborns operated their potteries in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century, as well as where the Paige Pottery was located. Although, it is certainly possible that they did not assume a role as full-time potters for Paige until the 1920s, seeing that Paige often advertised his business as a place that employed day-to-day “jobbers.”

Massachusetts author Lura Woodside Watkins (1897-1982) visited the Paige Pottery when it was in operation in the 1920s and/or 1930s, while she was researching and drafting her book, Early New England Potters and Their Wares. This is also where she witnessed the Paoluccis’ production while they worked for Paige and then when they acquired the pottery business sometime after 1945.

Watkins writes, “Perhaps the most famous craftsman employed at the Paige pottery was John Donovan, who was born in Exeter in 1851 and died in 1932. He was a turner for nearly 60 years, having become a skilled potter at the age of 15. I once watched John Donovan at work making kitchen bowls. He was able to complete one in from two to three minutes. One by one they would be laid on the drying board. Donovan meantime chatting quietly with his visitors; the board would be carried away, and he would begin another round. Speed was an important consideration in producing utilitarian vessels, but it took phenomenal skill to make them of uniform shape at the same time. During Donovan’s day, the Paige pottery sold commercially little herb pots with covers and a lip, almost identical to those made in the early days of potting. They were not made as reproductions, but in the ordinary course of events.

Twentieth Century pitcher described by Historic New England: “A redware pitcher with a pinkish white body and black spine on the handle and the rim. The body of the pitcher is decorated with a black, pink and green spiral decoration (on top of a tinenameled glaze). The pitcher was decorated by a girl of half Italian and half Argentine descent at the Peabody Pottery in 1926.” Courtesy: Historic New England.

“Edwin A. Rich, a Vermonter, worked in the pottery about 1880, and James Crawford Porter, an extremely able turner, was one of the later employees. Upon the death of John Donovan, the old tradition, too, passed away. Two Italians, Ermano and Luigi Paolucci, attempted to throw pots and to run the kiln, but they had not enough skill to do excellent hand work and they found machine methods unprofitable in competition with the great modern factories. They nevertheless turned out a number of interesting things in Italian style. These were principally pitchers and large deep dishes, tin-enameled, and painted in gay floral designs. They also succeeded in producing some colored glazes, such as a soft rose color, on a redware body.”

Today, not a lot is known about the Paolucci’s production, but the Peabody Historical Society does own a pitcher that the museum acquired when it was new from the Paige Pottery that indicates the Paoluccis were working with John Donovan. The pitcher retains its original lid and is described by the museum as a type of reproduction ware, whereas an old tag reads, “Made at Paige Pottery c. 1930 turned by John Donovan Glazed by Luigi Paolucci Black mat-glaze.”

Historic New England also owns a pitcher that seems to correspond with Watkins’ description of how some of the wares were made by the Paoluccis. The pitcher was acquired by the museum in 1926, the same year it was made, and is described as, “a redware pitcher with a pinkish white body and black spine on the handle and the rim. The body of the pitcher is decorated with a black, pink and green spiral decoration (on top of a tin-enameled glaze). The pitcher was decorated by a girl of half Italian and half Argentine descent at the Peabody Pottery in 1926.”

Peabody, Mass., City Directory, 1915, in which Ermanno Paolucci is listed as a potter working at 92 Central Street and Luigi Paolucci as a potter at 91 Central Street. There are records that spell the name variously, Ermano and Ermanno.

Furthermore, in 2010, Frank Kaminski sold a group lot of ephemera from a local Peabody estate at his Beverly, Mass., auction gallery. The paperwork for the lot included a letter written by a man named Enrico Caruso and addressed to Luigi Paolucci in Italian regarding imported pottery, presumably from Italy, dated January 28, 1914. The paperwork also included a postcard addressed to Luigi from the Knickerbocker Hotel in New York City, dated March 1918. This information may indicate that the Paoluccis could have also supplemented some of their income by selling imported Italian pottery in the Salem and Peabody area before 1920.

Another object of interest is a tin enameled red earthenware pitcher owned by the Peabody Historical Society, which the museum acquired from a local home in the 1980s. The history of this object is unknown, although its style of production is like how Watkins described some of the wares made by the Paoluccis. Interestingly, this type of pottery made by two Italian immigrant potters appears to be unique for known production in New England, whereas there are other related pitchers like this one owned by the Peabody Historical Society found with history of ownership in Peabody families, which are privately owned in New England today.