“The Quays, Dublin” by Evelyn Hofer, 1966, dye transfer print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser in honor of Brett Abbott, 2016. ©Estate of Evelyn Hofer.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

ATLANTA, GA. – Portraits are the focus of Evelyn Hofer’s work. Portraits of people, yes – and her portraits of people are like no others – but those people portraits are often embedded within larger portraits of cities, in the form of photobooks she published from the late 1950s throughout the 1960s, which are the focus of the present exhibition. This German-born, Swiss-raised, adopted New Yorker created frank and incisive images of postwar life in cities like Florence, London, New York, Dublin and Washington, DC. “Evelyn Hofer: Eyes on the City” is at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta through August 13.

“This is the first major exhibition of her work in 50 years in the United States,” says April Watson, curator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and co-curator, with Greg Harris of the High, of the exhibition. (The show will travel to the Nelson-Atkins September 16 through February 11, 2024). Both Watson and Harris lament that Hofer is not better known in the United States, where she ultimately made her home. “People who know photography have seen a picture here or there,” says Harris – perhaps her portrait of a young girl in Dublin on a too-large bicycle (“Bicycle Girl, in the Coombe,” 1966), or its US analogue of a young man in front of the Queensborough Bridge (“Queensborough Bridge, New York,” 1964), or her memorable photo of exhausted footballers after a match (“Phoenix Park on a Sunday, Dublin,” 1966) – “but they don’t know anything else about what she did.”

“Eyes on the City” seeks to redress that lacuna and carve out a place for Hofer in the canon of international photography. She worked against the grain of postwar photography, beginning in commercial and editorial work, steadfastly using large-format cameras and color film when her contemporaries were clicking away exclusively in 35mm black and white, and – partly because of the demands of her chosen equipment – carefully planning, timing, researching and composing each shot, rather than capturing spontaneous moments. “At the time, her work seemed kind of outmoded and passé,” says Harris, but with the hindsight of history – and the extraordinary work being done now by photographers like Rineke Dijkstra and Alec Soth (as Harris writes in his catalog essay) – it makes far more sense to see it as prescient and forward-looking. The prints, Harris says, “feel remarkably contemporary even though they’re 50-plus years old.”

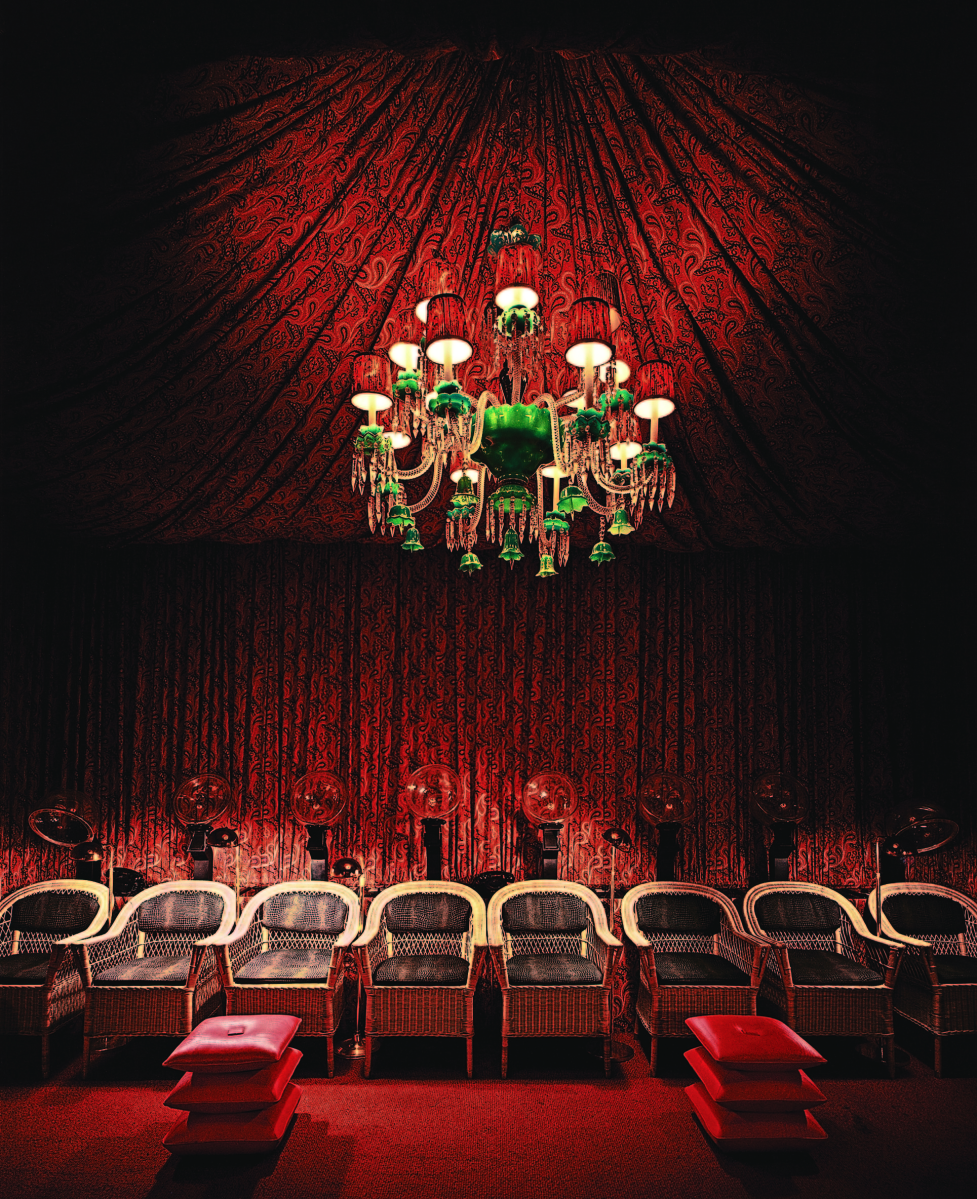

“Harlem Church, New York” by Evelyn Hofer, 1964, dye transfer print. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2016. ©Estate of Evelyn Hofer.

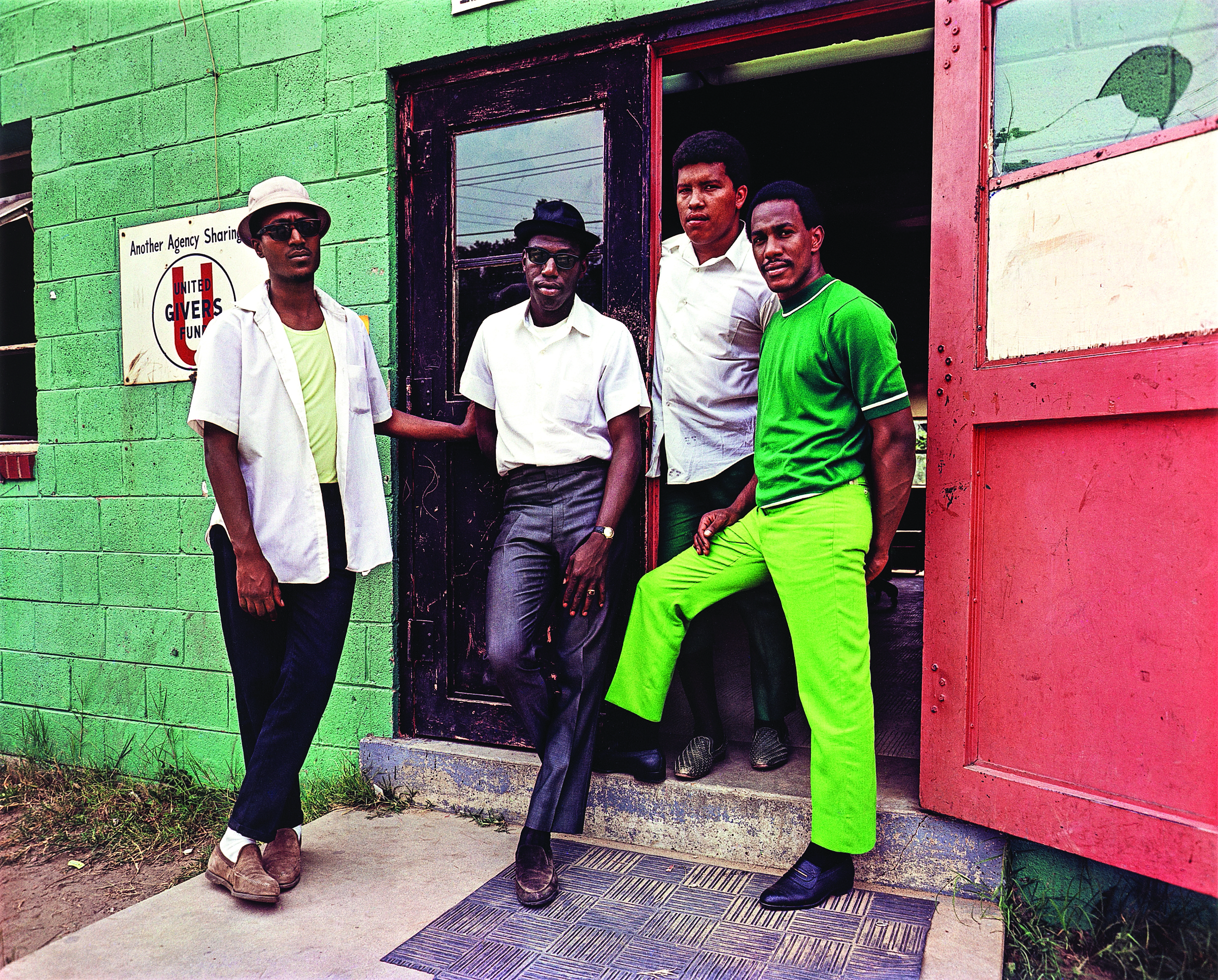

Take, for instance, Hofer’s image of four nattily clad young Black men standing in front of a United Givers Fund office in Washington, DC (“Four Young Men, Washington, DC,” 1968), or her portrait of a waitress at London’s exclusive, all-male Garrick Club (“Waitress, Garrick Club, London,” 1962). These are not spontaneous snaps; they are carefully composed and lit, and the people are all fully aware of and engaged with the camera. “It’s impossible to remain anonymous when you’re working with that kind of camera,” notes Watson. Harris adds that the camera required a tripod (so that it “couldn’t be blown over in the wind”) and that before each shutter click Hofer had to slide a 4-by-5-inch plate of film in place and step out from behind the camera. That “necessitated that she would talk to people; she would engage with them; she would have to tell them what she was doing, what she wanted from them. There was always a conversation.”

Each individual photograph, then, was a kind of collaboration, and each was also part of a larger collaboration with writers, publishers and printers that ultimately led to Hofer’s impressive corpus of photobooks. Collaboration did not always come easily. As Watson writes in her catalog essay, work on The Stones of Florence (1959) with writer Mary McCarthy, they had a rough start. The writer and the photographer had somewhat different ideas about the ideal relationship between text and image, and the “famously irascible” McCarthy had to be convinced that any photographs at all, and particularly Hofer’s photographs, would add value to her words. Hofer, meanwhile, who was no shrinking violet either, complained that McCarthy wanted to walk around the city together like “two Victorian women looking for pretty snapshots,” which was not at all what she had in mind. In the end, the Florence photographs reflect Hofer’s vision more than McCarthy’s words. While the latter focus on the hustle and bustle of a rapidly modernizing Renaissance city, the images are quieter, classical, focused on the eternal (“The Duomo, Florence” and “Badia di Fiesole, Florence”). They are portraits in a sense, but they are mostly portraits of buildings and of Florence itself, rather than people.

Despite the personality conflicts – and McCarthy came to praise Hofer’s work eventually – the Florence book was a success, and it led to a series of equally successful and more harmonious collaborations with other authors, notably the English author V.S. Pritchett. “They became very close friends, writing to each other throughout their lives,” says Watson. “That was a very fruitful collaboration.” Their collegial partnership led to three photobooks – London Perceived (1962), New York Proclaimed (1965) and Dublin: A Portrait (1967) – that represent a peak in Hofer’s artistic career. “This period is the time when she had perhaps the most personal creative control over the projects she was working on,” says Watson. Harris adds that “there was definitely a dialogue around how the work was being made, but it wasn’t like an editor was saying, ‘Here’s your shot sheet; I need everything on this list; hand in your pictures; thank you very much; we’ll see you later.’ She was guiding the process and was very much an author in these books.”

“The Duomo, Florence” by Evelyn Hofer, 1958, gelatin silver print. Estate of Evelyn Hofer. ©Estate of Evelyn Hofer.

In the Pritchett books – and in The Presence of Spain (1964) and Evidence of Washington (1966), with Jan Morris and William Walton, respectively – the images relate to the words but “don’t map on one to one with the text,” says Watson. “It was never really meant to be photographs illustrating the text, although there is a kind of synergy between them.” In this way Hofer’s own interests come through. Some of these interests are appealing idiosyncrasies: as “Bicycle Girl” and “Queensborough Bridge” show, she had a particular fondness for picturing people on bicycles (“There are at least three in the show,” says Harris). There is also a motorcycle cop posed somewhat incongruously in front of flowering cherry tree in Washington DC (“Springtime, Washington DC,” 1965). But other interests are more engaged with the complexities of postwar city life, including its social, economic and racial hierarchies.

Even in this, Hofer worked against the grain. While, like other photographers in the 1960s, she was interested in showing people from all walks of life and bearing witness to mid-Twentieth Century tensions of class, ethnicity and race, she rarely did so in an overtly political way. “There are lots of images of Black Americans in the media at this point, but they’re often pictures that in some ways either fetishize poverty or exemplify the violent struggle for racial justice,” Harris notes. Hofer was doing something else. In Evidence of Washington in particular, “there’s a lot of pictures of middle-class Black Americans at home, in a well-appointed living room, standing in front of a nice house.” Watson notes that Hofer was “really very intentional about writing out the people she wanted to photograph and get permission to photograph that would include some of the very esteemed members of the Black community.”

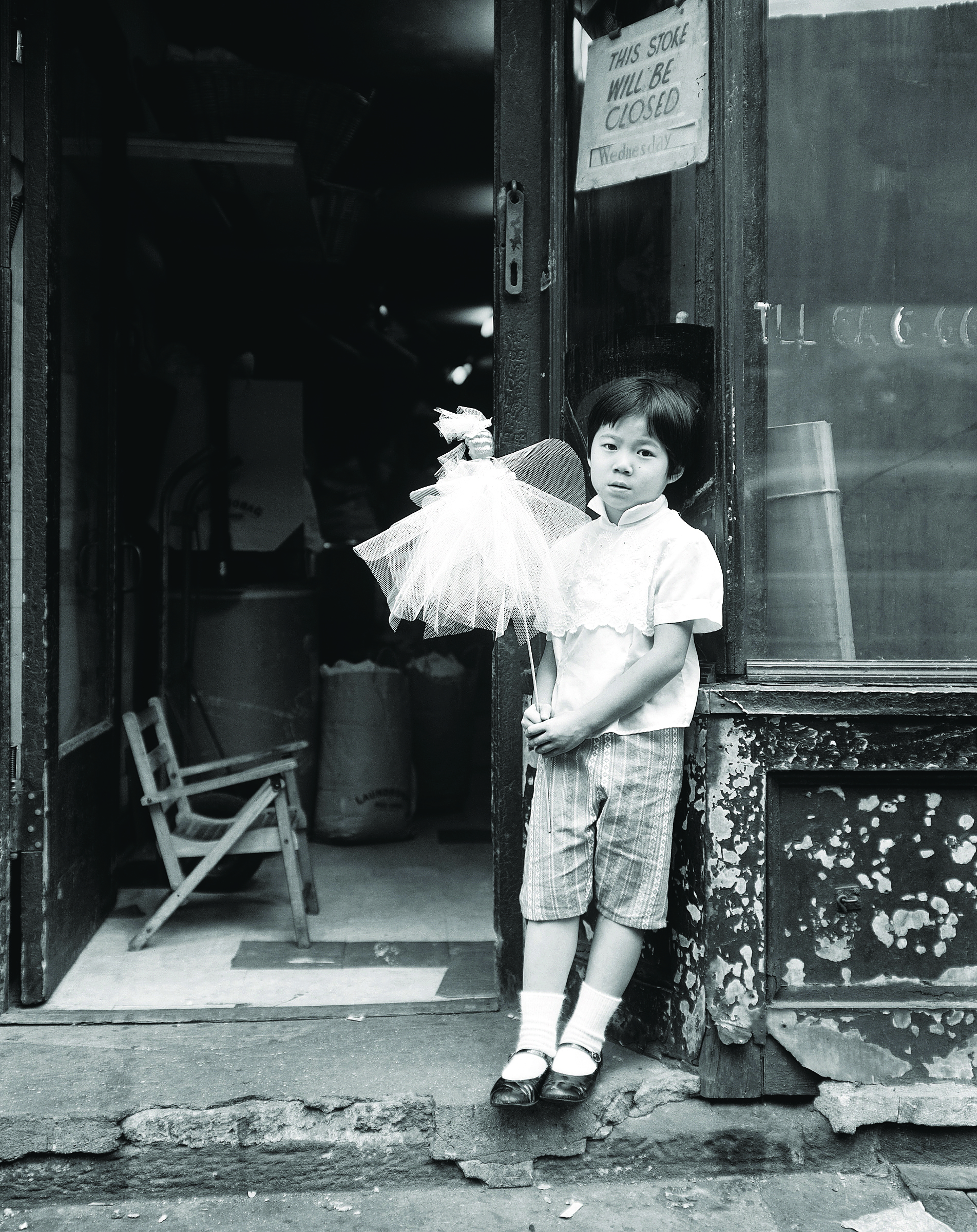

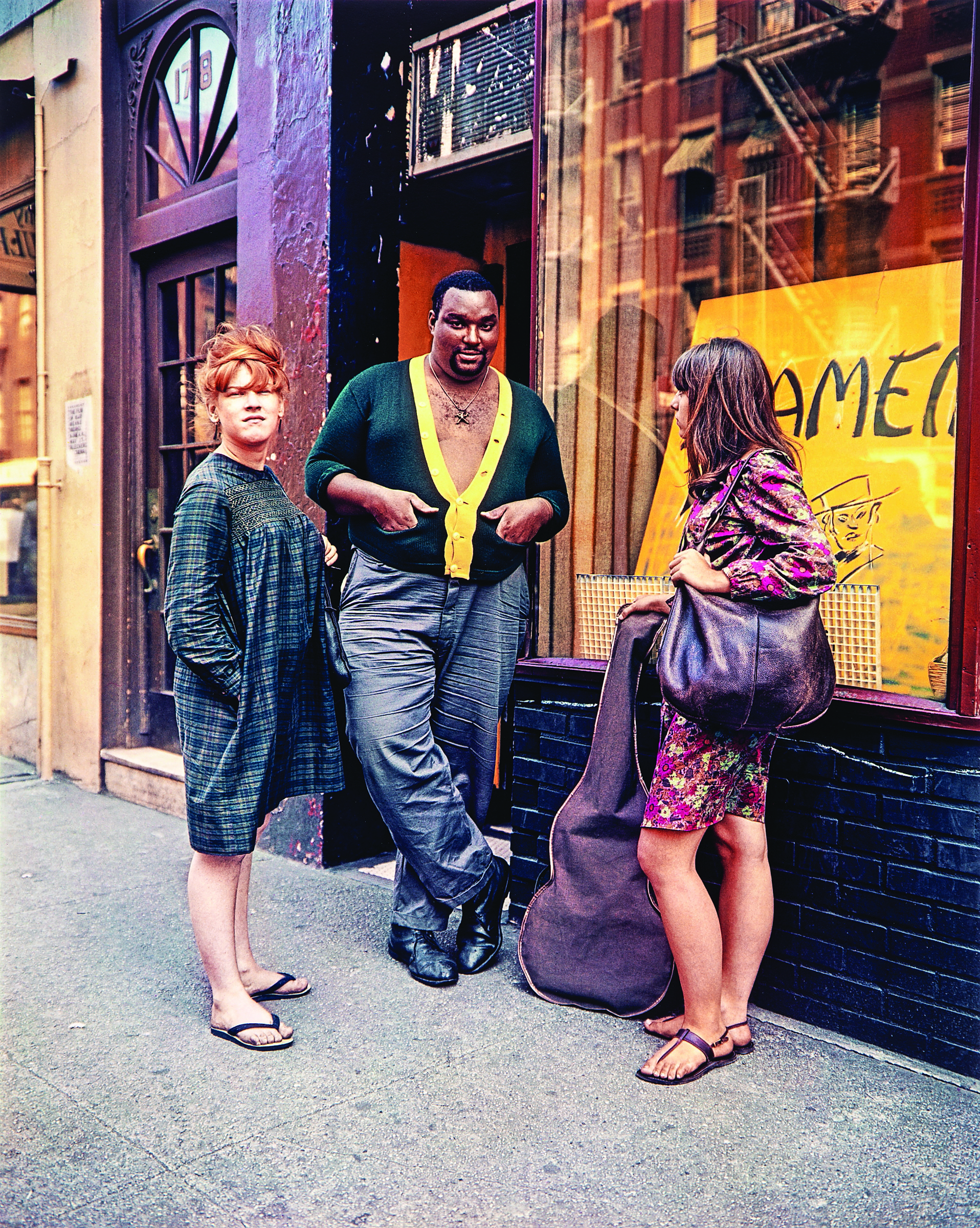

Both of the US books are “incredibly diverse” in this way, says Harris. The photographs of New York’s wildly varying neighborhoods and communities cover a cross section of humanity while nevertheless acknowledging shared, universal aspects of life. There is a surprising correspondence, for instance, between her photograph of Harlem church ladies (“Harlem Church, New York,” 1964) and Greenwich Village bohemians (“Greenwich Villagers, New York,” 1964), all standing in front of aging building fronts with signs in the windows and symbols above their heads. There is also the swaggering hot dog vendor (“Hot Dog Stand, New York,” 1963) and the little girl with a puppet-like toy standing outside what looks like her family’s Chinatown business (“Chinatown II [Little Girl], New York,” 1964). Watson notes that Hofer was very interested in peoples’ occupations, in how the jobs they did helped shape not only their own personalities but also the character of the city. It was one way, as Hofer put it, of getting “under the skin of the city,” her primary and persistent goal.

“Bicycle Girl, in the Coombe, Dublin,” by Evelyn Hofer, 1966, dye transfer print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser in honor of Brett Abbott, 2016. ©Estate of Evelyn Hofer.

Hofer remained interested in architecture as well as people as a means to craft a portrait of a city. Harris notes that the large-format camera she used had special advantages for photographing buildings. “If you have a camera with a fixed back and a fixed lens, everything kind of converges at a single point, but what you can do with a view camera is you can tilt the back and straighten out all those lines…You can make these very precise, orthogonal pictures that look very rational; they look like a Renaissance painting because she can control the perspective in such a precise way.” This is apparent in the Florence pictures – head-on shots of the Duomo and other sites – but also in more distant views of Dublin’s harbor (“The Quays, Dublin,” 1966), London’s central waterway crisscrossed by bridges (“Thames Bridges, London,” 1962), or New York’s skyline seen through a screen of walking commuters and their shadows (“42nd Street, New York,” 1964). In one remarkable photograph, that famous skyline competes with a mass of highways “converging and tangling into the city,” as Harris puts it (“Arteries, New York,” 1964). “It adds a totally different dimension to how to portray New York.”

“Evelyn Hofer: Eyes on the City” was co-organized by the High and the Nelson-Atkins, both of which had acquired significant bodies of work by Hofer and, through gallerist James Danziger, realized that both were working toward exhibition and book projects. Danziger connected both institutions with the Hofer estate in Heidelberg, Germany, led by Andreas Pauly, and a mutual decision was made to focus on this period of intense activity while Hofer was producing her photobooks. The exhibition includes the books themselves; printed and framed photos produced either as part of the book projects or later, for exhibition or sale; and some work, both commercial/editorial and artistic, from both before and after that period of focus. There is also her camera, an unwieldy, almost steampunk-looking thing with an accordion-fold body and a 4-by-5-inch viewfinder.

“Photographers who work with view cameras say it’s slow photography,” says Watson. “It takes time, and you’re thinking about all these technical considerations; you’re thinking about the artistic considerations; you’re going back and forth; you’re not just snapping it and walking away.” This carries through to Hofer’s photos as well. They bear close and repeated looking and careful consideration – not only in person, in this exhibition, but in the larger history of photography as well.

The High Museum of Art is at 1280 Peachtree Street Northeast. For information, 404-733-4400 or www.high.org.