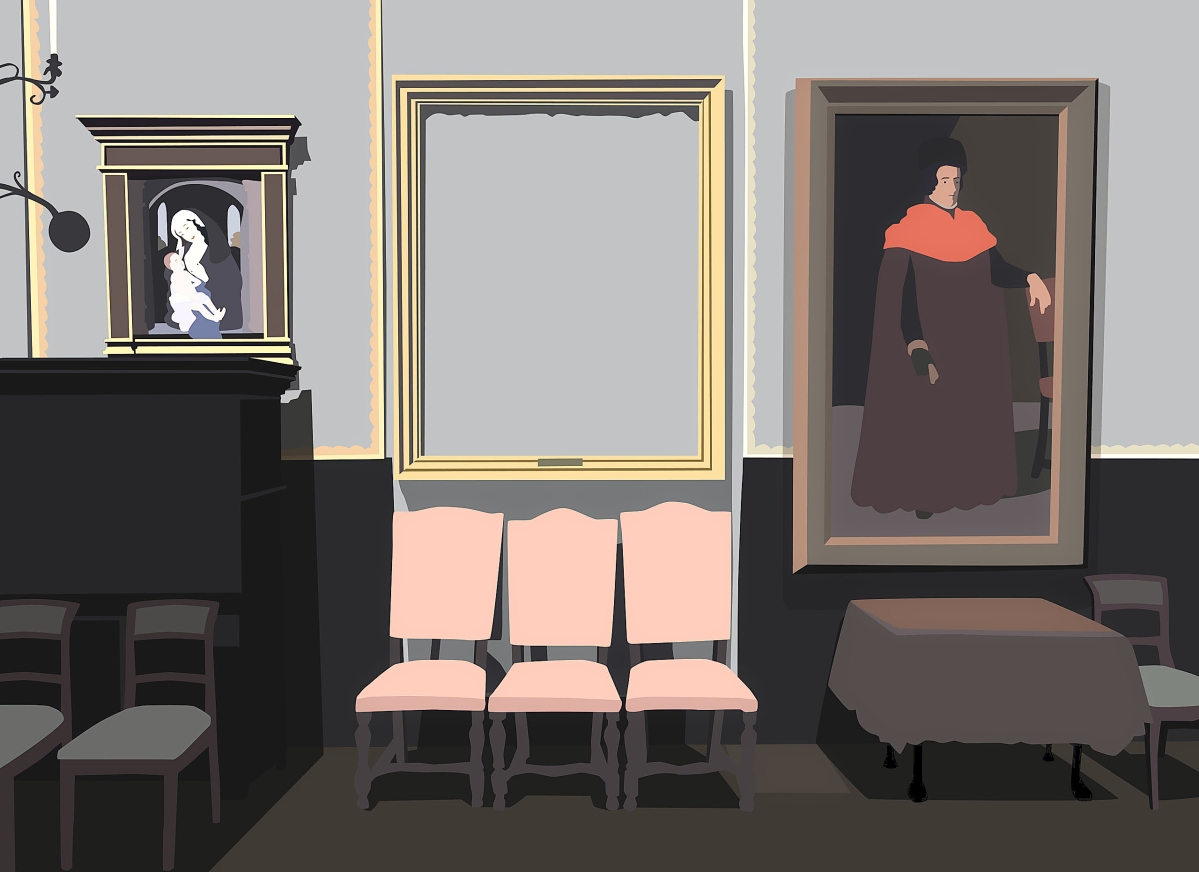

“Empty Frame” by Kota Ezawa (Japanese-German, b 1969), 2015. Duratrans transparency and LED light box, 24½ by 33½ inches. Courtesy of the artist, Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica, and Haines Gallery, San Francisco.

By James D. Balestrieri

ATHENS, GA. – An exhibit is a public display of artworks or other objects of cultural interest in a gallery or museum. An exhibit is also a piece of evidence produced in a court of law. When these two definitions cross paths in crimes – heists in particular – public interest peaks and is piqued. Art crime. Journalists and documentarians circle. Fiction swoops in. Hollywood pounces. From Topkapi to How to Steal a Million, from The Thomas Crown Affair (both versions), to the Ocean’s movies, to Lupin, art crime exudes a certain sex appeal, a bloodless, victimless Robin Hood vibe: intricate planning, cool characters and danger with flair.

Of course there are other kinds of art crimes, the most egregious of which are the seizing of thousands of works from private and public collections by the Nazis and the wholesale looting of colonial Africa, Asia and the Americas in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries to fill mansions and museums in London, Paris, New York and elsewhere.

Yet when you work back from the righteous, smooth Assane Diop, the protagonist in Netflix’s French hit Lupin to the clumsy crew that pulled off the greatest art heist in history on March 18, 1990, at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in the Netflix series This Is A Robbery, the romantic archetype of the suave art thief comes to earth with a thump.

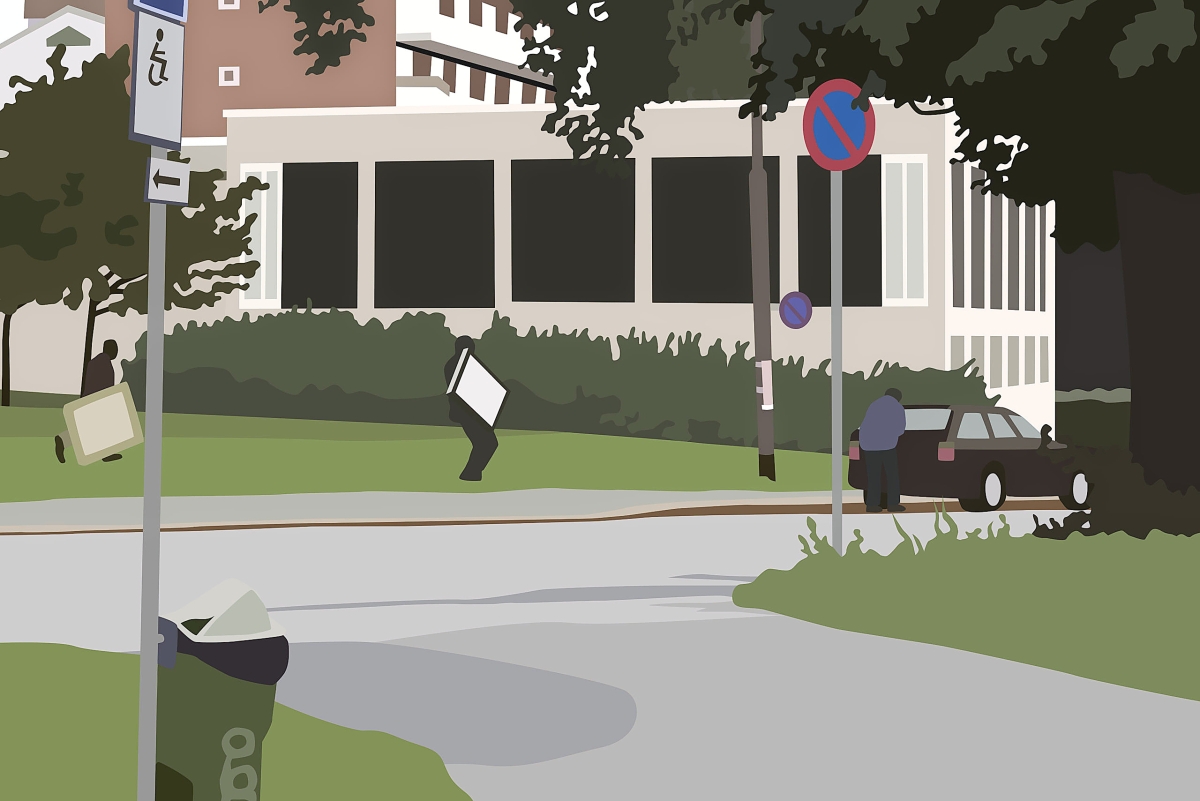

Our fascination with art crime and the vast gulf between our perceptions of it and the grittier realities is one of the subjects of Kota Ezawa’s “The Crime of Art,” opening at the Georgia Museum of Art. Ezawa also locates the deeper theme of his work in contemporary art practice with its emphasis on the copy: on digitization, simplifying, sampling and remixing – which he wants us to consider as – just perhaps – another species of stealing.

The story – just the facts. On March 18, 1990, a guard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum let two men posing as police officers, who claimed they were responding to a call, into the museum. The men bound the guard and his partner and went to work. Over the next 90 minutes or so, they took small works off the walls and slashed large canvases from their frames. On the list, three Rembrandts: a self-portrait, “A Lady and Gentleman in Black” and “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” A wonderful Vermeer, “The Concert,” a Manet and five works by Degas. They also took a postage-stamp size Rembrandt etching, a Chinese vase and an eagle finial from a Napoleonic standard. Rumors and conflicting stories abound. No one has ever admitted to the crimes. No one has been charged. The value of the works is now approaching a billion dollars. To honor Isabella Stewart Gardner’s wishes that her artworks never be removed from the building, the empty frames fill the spaces where the paintings once hung. Visitors flock to the museum to see the frames.

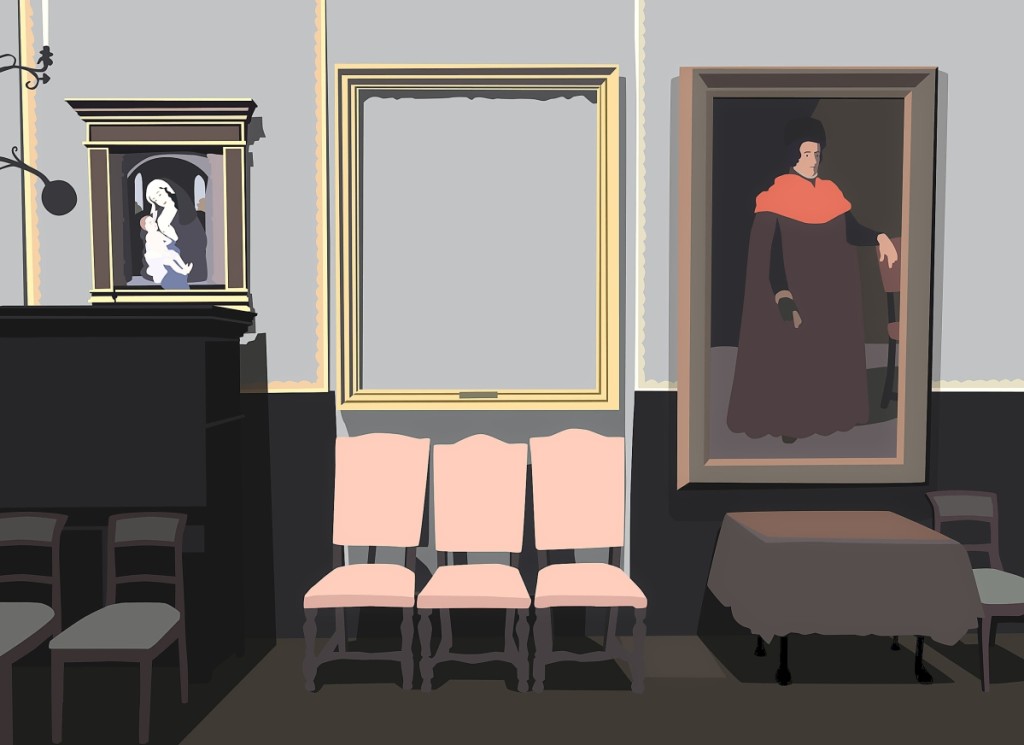

“The Storm on the Sea of Galilee” by Kota Ezawa (Japanese-German, b. 1969), 2015. Duratrans transparency and LED light box, 62½ by 50½ inches. Courtesy of the artist, Collection of Nion McEvoy and Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica.

Think about that. The absence of the artworks and the empty frames attract visitors.

The works in “The Crime of Art” are backlit images in lightboxes. They can be turned on or off with the flick of a switch. If the light goes out, art goes dark. Further, with the originals gone, what remains are copies, photographs, transparencies – in short, ghosts. There and not there. Art is ephemeral, Ezawa suggests. Art can vanish like that. Think of what has been lost through war and conquest, through natural disaster, through sheer neglect. Further, the way Ezawa reduces the images to essential forms and a limited palette indicates the losses sustained when we lose art. There is an analogy to be made here with ancient texts. For example, we only know the two dozen or so works of Democritus through fragments and descriptions written by others centuries later yet even those shards tantalize and make us long for more.

Through Ezawa’s practice, the stolen artworks, the frames that hang in their places, the stills from the security footage on the night of the robbery, all are placed on an equal footing. Each is apprehended, as in taken; each is apprehended, as in understood, to the same degree. Leveling the story of the artworks, making them into a kind of sequential art, comic book narrative – unified under Ezawa’s personal, minimal yet hands-on style – offers insight into how we view and think about art as a cultural and economic commodity, as a medium of exchange between the artist as thief, the collector as thief, the museum as thief, the viewer as thief, the thief as thief – and also as another order of consumer.

Netflix’s This Is A Robbery came out just as I was about to visit the Isabella Stewart Gardner for the first time in my life. The story is a nested tale with a few mirrors in infinite regression thrown in. Boston mobsters and a thief with a good eye for art. Suspects murdered, others mum. A plot hatched in a garage that moves to a warehouse in Red Hook, Brooklyn, where a journalist is taken blindfolded, and shown what might be “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee” – or not. A story told by an aging hood making pasts for other aging hoods in the grease pit of a derelict used car lot. Evidence lost or mishandled. Leads missed. A mounting, massive reward never claimed.

What was clear in the documentary – and not much is – is that the reasons for stealing art have little to do with secretive billionaires whose passion and covetousness ensure that he and only he – it is always a he – will never let other eyes than his see the treasure. So much for that Hollywood trope.

In truth, stolen art is hard to move. Finding no buyers, thieves often abandon or even return works they have stolen. In fact, there are only three reasons to steal art: as collateral, as an alternative method of payment and as leverage. An artwork or collection can be collateral in all manner of illicit dealings. Alternative method of payment? Ever wonder why nondescript works of art sometimes achieve ridiculous prices at auction? I do. What better way to launder money, in full view, publicly, and yet unbeknownst to anyone, even the auction house? And finally, leverage, which is the conclusion that This Is A Robbery comes to with regard to the Isabella Stewart Gardner heist. Here’s the story, according to Netflix: the Gardner was robbed so that mobsters in jail would have their sentences reduced in exchange for revealing the whereabouts of the art. If that was the reason, it didn’t work. Or hasn’t yet. But if the documentary has named the right names, most of the principals are no longer with us as a result of Father Time or lead poisoning.

Installation image, “Kota Ezawa: The Crime of Art,” on at the Georgia Museum of Art through December 5.

When I visited the Isabella Stewart Gardner with my family, I expected to feel sadness when I stood in front of the empty frames. Sadness is what most say they feel. What I felt was anger. The same anger I felt when I saw the fragments of the Andrea Mantegna’s frescos in a chapel in Padua (Giotto’s, not far away, escaped the Allied bombs). The same anger I felt when the Buddhas at Bamiyan were destroyed. The same anger I felt when the ruins of the city of Palmyra were razed to rubble. As much as I admire Ezawa’s work – the thought that went into it, the ideas that spring from it, I find that my visceral reaction obliterates aesthetic theory and semiotics. I do admire Ezawa’s detachment and ability to make art out of abject travesty. I don’t know how he did it. I couldn’t.

The food at the Gardner is fantastic and we availed ourselves of an excellent lunch after our visit. On the way out, we took in Shen Wei’s monumental exhibition, “Painting in Motion” that walked the line between abstraction and the great monochromatic ink paintings of the Northern Sung period in China. Before we went back out into a Boston rain for the drive home, I raced back to have a last look at Sargent’s “El Jaleo,” thankfully unmolested by the thieves, no doubt by dint of its size alone. In that moment, presence filled absence and some of the anger drained away. It was as if the empty frames had snapped off a light – in me, in one of Ezawa’s lightboxes – and that it had taken something else, Shen Wei’s work and “El Jaleo,” to turn it back on again. I could imagine the frames filled, the ghosts sent back to wherever it is that ghosts live. I’ll still watch art heist movies – I love them and their suave protagonists and the intricacies of their plotted mechanics – but I will watch them through thick lenses of fiction. As Kota Ezawa’s work demonstrates, the reality of art crime is almost too much to bear.

The Georgia Museum of Art is at 90 Carlton Street. For information, https://georgiamuseum.org or 706-542-4662.