This contemporary drua (double-hulled sailing canoe) was commissioned as a heritage project in Fiji to encourage the retention of canoe-building skills. Joji Marau Misaele managed the project in Fiji with the drua building team — carvers and mat-sail-makers — originally from the islands of Ogea and Vulaga in the Lau region. The team harvested trees from the forests on Ogea and completed the canoe, which has no metal components, using traditional tools, fiber lashings, and shells. The sail is composed of six sections of hand-woven pandanus-leaf matting, which prevents tearing of the entire sail. Without a fixed bow or stern, drua can sail in either direction. In the Nineteenth Century, large double-hulled canoes provided effective open ocean transportation and carried troops in times of war. Installation photograph, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

By James D. Balestrieri

When I was very young, I used to find myself in the Coin and Stamp Department in Gimbel’s on Wisconsin Avenue in Milwaukee. I would be feeling the sting of my weekly allergy shot, received with a stoic wince in Dr. Lee’s office down the block. One day, while my mother was at Gimbel’s Delicatessen – I can still smell the clovey, molassesy ham they made – I was peering, as usual, over the wooden counters at some rarity I coveted. Beside me, a tall, elegant, silver-haired woman was bargaining – arguing really – with the numismatic salespeople – all men, all in suits and ties – trying to sell her late husband’s coin collection. She was in a hurry, and vocally unsatisfied with the agreement they came to. Then she said, “Now, about the stamps.” Philately chimed in from the next counter: a proper appraisal would be required, etc, etc. The woman leaned down to me and said, “Little boy, do you like stamps?” Startled, I stammered, “Yes,” and before I could say another word, the woman commanded the salespeople to “Get this young man some bags. The stamps are his.” And so they were.

You can imagine the look on my mother’s face-and the line of interrogation – when I appeared in the deli with two bags full of stamp albums. When I got home, the first stamps that really caught my eye were some bright, beautiful 1930s stamps from Fiji. Since then, Fiji has always had an association for me as an El Dorado of sorts, a paradise so remote from my experience that I could scarcely imagine it.

“Fiji: Art and Life in the Pacific,” on exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), goes a long way toward dispelling my notions of exoticism in regard to Fiji, though I must admit, it makes me want to travel there all the more. More than 280 objects drawn from the Fiji Museum, the British Museum, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, the Smithsonian and fine private collections, are featured in the exhibition, making this by far the most extensive presentation of Fijian art ever mounted in the United States. The excellent accompanying catalog, written by Steven Hooper, professor of visual arts and director of the Sainsbury Research Unit for the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, is an indispensable aid in coming to grips with the complexities of Fijian history, society and culture and in placing the objects on view in proper context.

The title of the exhibition creates a linguistic division between “Art and Life,” which raises immediate questions and demonstrates the difficulty for us, raised in the Euro-American tradition, to apprehend a society in which art is inseparable from life, in which, in many ways, art is life, and, conversely, life is art.

In fact, in the Fijian language – as in many, maybe even most languages around the world – there is no word that means “art” as we mean art. By art, in Western terms, I am thinking of art as a reality of its own, an aesthetic reality detached from and running alongside the reality we inhabit, an art – born of leisure, and of a philosophical separation between sacred and secular realms – that dips into reality as a brush dips into paint, that makes use of reality without claiming to represent any reality other than that of the artist.

A single instance of the differences between Fijian and English, as Hooper writes in the catalog, highlights the difficulties: “The single English word ‘you,’ which is indiscriminate in Fijian, is rendered by four different terms which indicate singular, dual, few and numerous (koiko, kemudrau, kemudou, kemuni). There are dual, few and numerous terms for ‘them,’ as well as separate inclusive and exclusive terms for ‘us’ (two people, including or excluding the interlocutor, a few people, and so on). The linguist George Milner explained to me years ago, only half in jest, that Fijian, with its highly complex pronouns but lack of complexity in tense (a simple past, present and future) was the diametric opposite of English, which had impoverished pronouns but complex tenses (past perfect, pluperfect, etc). He associated this with the differing concerns of the two cultures – that Fijians were intensely interested in social relations, in who was involved in something, but were not so obsessed with time.”

A single instance of the differences between Fijian and English, as Hooper writes in the catalog, highlights the difficulties: “The single English word ‘you,’ which is indiscriminate in Fijian, is rendered by four different terms which indicate singular, dual, few and numerous (koiko, kemudrau, kemudou, kemuni). There are dual, few and numerous terms for ‘them,’ as well as separate inclusive and exclusive terms for ‘us’ (two people, including or excluding the interlocutor, a few people, and so on). The linguist George Milner explained to me years ago, only half in jest, that Fijian, with its highly complex pronouns but lack of complexity in tense (a simple past, present and future) was the diametric opposite of English, which had impoverished pronouns but complex tenses (past perfect, pluperfect, etc). He associated this with the differing concerns of the two cultures – that Fijians were intensely interested in social relations, in who was involved in something, but were not so obsessed with time.”

If art in the Western World is obsessed with anything, it is obsessed with time – with individual and collective memory, with history, with death. In Fiji, the bedrock of culture is vanua or land, an idea embracing physical land – earth, soil and its bounties – bounded territory, and, most importantly, custom or traditional actions. Vanua “has intense emotional force for Fijians…The vanua contains the actuality of one’s past and the potentiality of one’s future. It is an extension of the concept of self.”

Through elaborate feasts and rituals, important events are commemorated – funerals, marriages, birthdays – and relations between families, clans and peoples are cemented or renewed. At these feasts, the chief, who is always seen as a creature of the sea, receives abundant gifts. Beautifully woven barkcloth mats and clothing are presented. Yaqona, a drink made from the roots of a pepper plant and served in wonderfully wrought wooden bowls, is shared. These are considered female products of the landspeople. Food – things grown, gathered and hunted – are male offerings. Shields made from shell and whale bone, clubs and spears carved from wood and decorated, these are chiefly products made by men who are often the same craftsmen responsible for constructing the magnificent ocean-going sailing vessels, the largest of which are called drua.

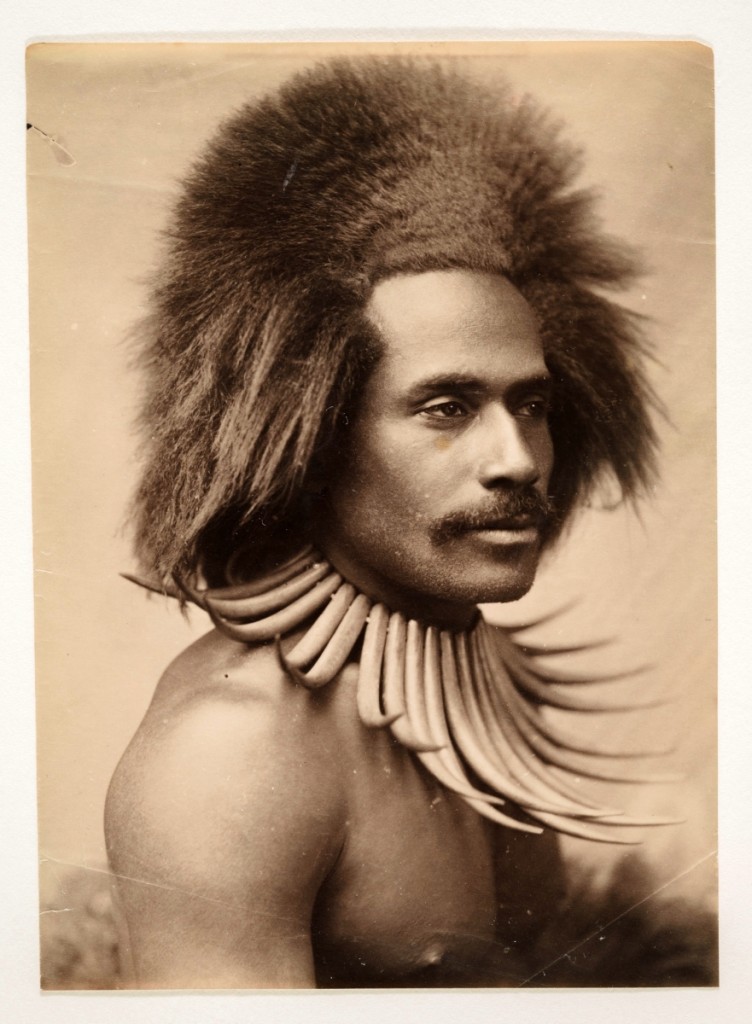

Hooper writes, “A logical extension of the association of chiefs with the sea and with sea products, such as whale teeth and various species of shells, is that chiefs’ bodies should be adorned with these materials. At one level of analysis they are equivalent substances, embodiments of divinity – this is what gives the tabua its power and significance – so ivory and shell regalia can be seen as extensions of the chiefly body, splendid to behold.”

Whale teeth, or tabua, carved and worn as pendants and sometimes smoked to give them a reddish appearance, are gifts of special importance and value. But, as Hooper writes, the life of a chief is a life of sacrifice. Chiefs are installed and can be removed, especially if they are seen as miserly. Chiefs “are expected to deliver abundance, and although a regular stream of feasts and valuables may come their way, these should all as quickly be redistributed in obligatory expressions of largesse.” Hooper goes on, “the qualities that most define a chief are generosity towards the people, loving the people and making sure they have enough to eat.”

“Fijian Warrior (with Whale Tooth Necklace)” probably by John William (J.W.) Waters, 1880s. Albumen print, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Partial gift of Mark and Carolyn Blackburn and purchased with funds from LACMA’s 50th Anniversary Gala and Fiji Water. Photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

When we look at the indigenous objects in the exhibition – there are also crucial pieces of colonial origin – we can marvel at the craftsmanship and apply our standards of beauty to them – admiring their forms, design, composition, intricacy and so on – but I’m not at all sure these aesthetic categories mean much in Fijian terms. Imagine talking about Michelangelo’s “Pietà” without making any reference to Christ and Mary and you get some idea of what I am thinking about.

Consider the breastplate made of deep purple pearl shell surrounded by polished sections of whale bone deftly fit together with coir braid. The size of the shell alone boggles the imagination and the inlays of whale bone: stars, moons and sun, suggest the chief’s marine origins, the night sky over the sea, but in form they seem astonishingly proto-modern, as if the makers of the piece had looked at Matisse or Picasso – instead of the other way around. A breastplate of this quality was worn by chief Ratu Tanoa when the Wilkes Expedition (known as the Ex. Ex.) visited Fiji in 1840 and then, in turn, was given by his son, Ratu Cakobau, to Sir Arthur Gordon, Fiji’s new British Governor, in 1875. When you learn that the breastplate appears in a painting by one of Wilkes’s artist-scientists, Alfred Agate, in 1840, and appears again in a painting by Constance Gordon-Cumming in 1876, and you learn that other similar breastplates such as the one pictured were highly prized yet freely given when the occasion called for a tabua of such value, you get a glimpse into a culture that values art in a different way. Inherent in the work is the natural origin and value of the work’s raw materials, the craftsman’s lineage and fealty to the chief, to nature and to the gods, all of which are expressed in the craftsmanship. Then there’s the history of the work’s presentation and ownership – where it’s been, when it’s been worn, the ceremonial vanua enacted around it, its transactional history of having been given and received. All of this must be seen as possessing an unbroken spiritual value.

Unlike other indigenous peoples who came under colonial rule, the complexity and sophistication of Fijian society acted as something of an insulator against the worst excesses of occupation and exploitation. Fiji has preserved more of her culture than most. Christianity, which is practiced by most Fijians, is, to this day, mixed with traditional beliefs and rituals. Fijians have proven remarkably adaptable in other areas as well, transforming the beauty of their weaving into inspiration for a burgeoning fashion industry.

I pulled out the old stamp album as I was preparing to write this article and took a look at those Fiji stamps. They put me in mind of a story I read as a kid in Robert Arthur’s Ghosts and More Ghosts. In the story, two guys find some gorgeous stamps from a tropical country called El Dorado. Only there is no El Dorado. They use one to send a letter to a fictitious address. The letter flies out the window and vanishes, only to return in a minute postmarked “Addressee not known.” Something like that. Then they attach a stamp to the collar on a rheumy old cat. The cat flies out the window and returns a minute later – but renewed and full of life. Seeing this, the narrator’s friend says, “That’s it. I’m going,” affixes some stamps to his shirt, and flies out the window. Some days later, the narrator gets a postcard from his friend: postmark El Dorado. The postcard describes an island paradise. I noticed my Fiji stamps are still in mint condition – unused, uncanceled. I wonder…