By Ed Polk Douglas

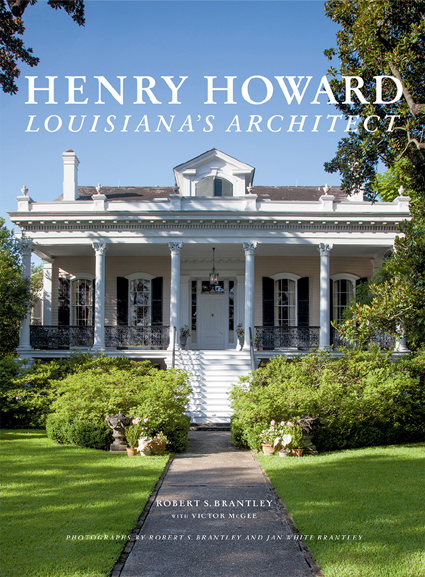

Henry Howard: Louisiana’s Architect by Robert S. Brantley with Victor McGee, published by Princeton Architectural Press and The Historic New Orleans Collection, www.papress.com or www.thnoc.org, 2015, hardcover, 352 pages; $60.

The book cover depicts the Greco-Italianate-style Antonio Palacio house, built 1867, an elegant example of the mansion-like “cottages” in the residential suburbs of New Orleans praised by Mark Twain.

In spite of a continuous history of both natural and manmade disasters, Louisiana and particularly New Orleans still have some of the most interesting and varied architecture in the United States. This often quirky construction trail stretches from the Eighteenth Century to the present.

Comments on building forms and methods there have often appeared in travelers’ accounts. A. Oakey Hall’s The Manhattaner in New Orleans, 1851, called the mélange he saw “more striking and absurder” than anywhere else; Mark Twain in Life On The Mississippi, 1883, was enchanted by the homes in the American sector (today’s Garden District) but felt that a “great fire” followed by massive rebuilding would vastly improve the commercial areas.

For better or worse, old buildings are a fact of life in Louisiana, and, while volumes on local history and building types continue to appear, detailed studies of individual architects, particularly those from the Nineteenth Century, have languished.

Thus, the handsome new book, Henry Howard, Louisiana’s Architect with photography by Robert S. Brantley and Jan White Brantley, chronicling the life and the four-decades-long career of a very talented Anglo-Irish émigré, the creator of some of the area’s most iconic structures, is a welcome addition to the catalog of works surveying American regional architects.

Of English ancestry but born and reared in County Cork, Ireland, Howard (1818–1884) came from a family deeply involved in the building trades. He arrived in New York City in 1836 better trained than most of his American contemporaries. New Orleans offered family connections and seemingly more opportunities, so he settled there in 1837. Continuing his practical studies locally with several talented professionals, he began to build a network of important clients, both urban and rural.

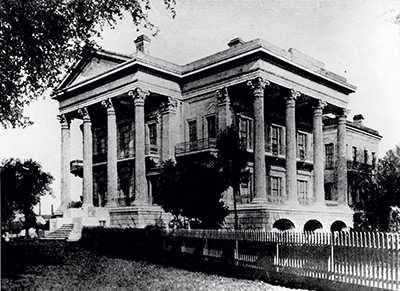

Belle Grove Plantation, Iberville Parish, La., 1853–57 (destroyed), Greek Revival, was possibly the largest plantation house built in the antebellum South. Copy photograph by Clarence John Laughlin, August 13, 1952 from circa 1888 original; the Clarence John Laughlin Archive, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

The nadir of his career came in the 1850s when New Orleans was one of the most prosperous cities in the country. Howard’s business suffered during the vicissitudes of the Civil War and Reconstruction, but his work retained its quality. After his death, his reputation faded, and, by the early Twentieth Century, his buildings were often ascribed to others.

Howard produced structures in all types and sizes; although not a “tastemaker,” his work in the revival styles of the era — Grecian, gothic, Italianate and French — blended American and European influences to create distinctive forms. Because he was competent in both design and construction matters — although preferring the former — he raised local building standards. His surviving work continues to please aesthetically and perform functionally.

The Crescent Billiard Hall, New Orleans, 1875, Italianate, is still a prominent landmark on Canal Street. All photographs by Robert S. Brantley and Jan White Brantley unless otherwise noted.

This book has been carefully crafted with both the amateur and the specialist in mind though the latter should be aware that there are some factual errors and surprising omissions throughout. The useful back matter includes copious footnotes and an extensive bibliography; the illustrations, both modern and archival, are numerous and superb. The catalogue raisonné lists more than 300 documented or attributed projects in three states (Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia), about a hundred of which survive. Presumably, more “Howard-iana” will emerge once the data within the book are disseminated; an invaluable discovery would be the architect’s office records, sold in 1881.

The evolution of the book is an unusual story that stretches back almost 70 years. New Orleanian Victor Magee (1932–2007) “discovered” his great-great-great-grandfather’s architectural career as a teenager, and a publication to rehabilitate Howard’s reputation became his lifelong passion. It was an obstacle-strewn course, and while Magee’s enthusiasm even captured me, already a Howard devotee, in the early 1970s, our professional collaboration was fruitful but book-less.

New Orleans’ Upper Pontalba buildings, 1849–50, Greek Revival, are one of two matching, multiuse rows that face Jackson Square in the heart of the Vieux Carre. They demonstrate probably the earliest use of large scale, cast iron galleries in the city.

Georgia native and professional photographer Robert S. Brantley met Magee soon after he moved to New Orleans in 1977, having read a mention of Howard in my 1974 volume, Architecture In Claiborne County, Mississippi. Soon, they began a lengthy “partnership” whose unquestionable goal was a book; in time, they were joined by Brantley’s wife Jan White (1952–2008), a staff member at the Historic New Orleans Collection as well as a photographer. The work of this trio is the basis for the current book, yet, along the way, both Magee and Jan Brantley died. Bravely, Brantley continued the project, and there is finally success. “Creation is a patient search,” wrote the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, and, certainly, this book exemplifies this dictum.

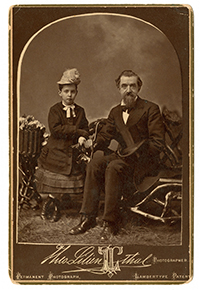

Henry Howard and Ida Caroline Howard, photograph by Theodore Lilienthal, February 21, 1877, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Nowadays, with new monographs on pre-1900 American regional architects uncommon, the fact that this book, which debuted in June, now in its second printing, indicates a well-deserved national audience. A related exhibition, “Henry Howard’s New Orleans, 1837–1884,” will run at the Historic New Orleans Collection November 18–April 3.

Mississippi-born author Tennessee Williams felt that there were three “great cities” in the United States: New York, San Francisco and New Orleans. Aficianados of Nineteenth Century American architecture are fortunate that Howard chose the latter as his home, since his work has fared better there than it might have elsewhere. Those structures have charmed locals and visitors for many years, even if their creator’s name was forgotten. Certainly, Henry Howard will bring this man’s oeuvre a new appreciation, and I, for one, am delighted.

Ed Polk Douglas, Lyons, N.Y., is a Mississippi-born architectural historian and decorative arts consultant.