“Jungle Orchids and Hummingbirds” by Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), 1872. Oil on canvas, 18¼ by 23 inches. Yale University Art Gallery, Christian A. Zabriskie and Francis P. Garvan, BA, 1897, MA (Hon.) 1922, Funds.

By Kristin Nord

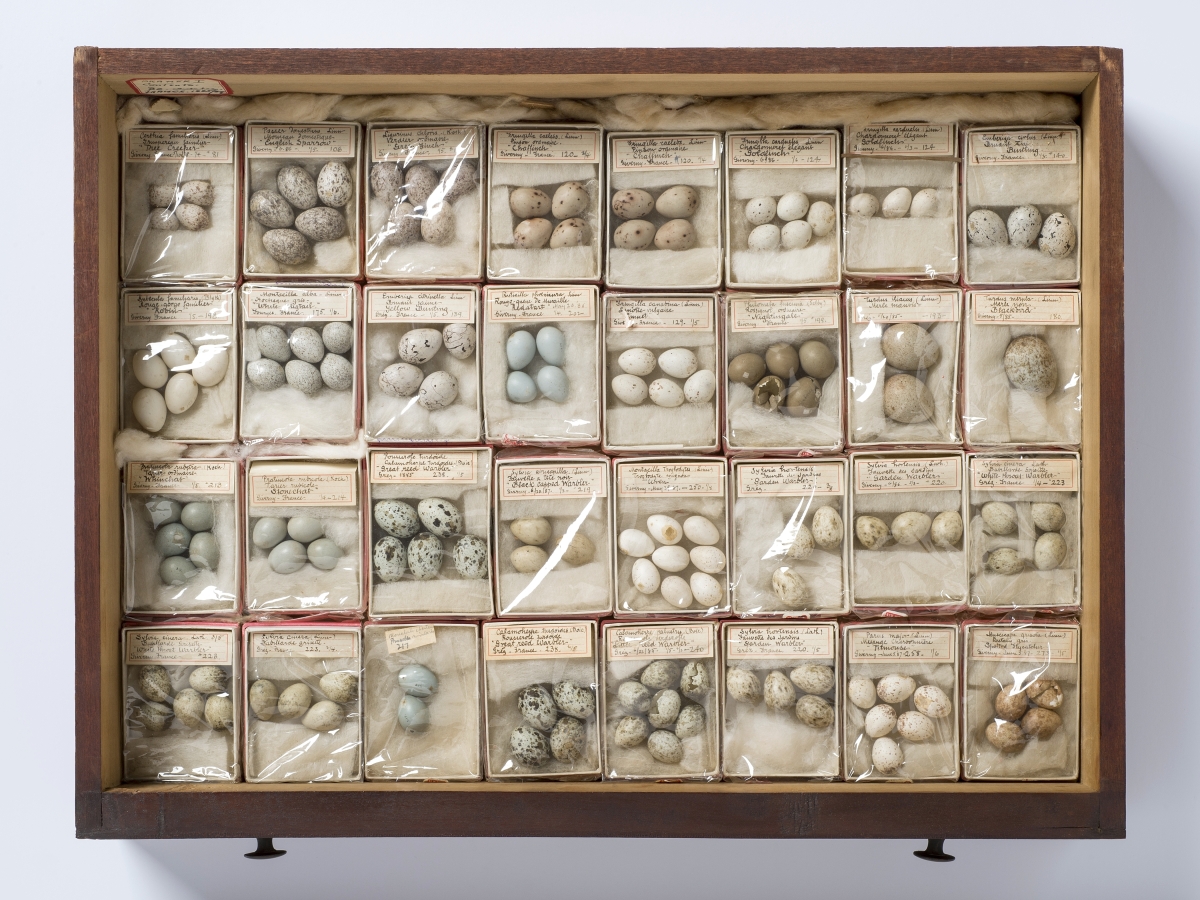

OLD LYME, CONN. – Tucked away at the Florence Griswold Museum is a magnificent mahogany chest filled with treasures. One drawer stores 38 glass-mounted moths and butterflies, with many furry bodies and wings still displaying their original deep gold, bright yellow or rosy pink pigments. In another drawer are 32 boxes of tiny eggs of birds, from one attributed to the English sparrow to the creamy blue egg of a redstart.

“While collecting actual specimens such as plants, insects, shells and minerals may have been the first instinct of any naturalist, for the artist-naturalist creating drawings of them was often the next,” Dr Jennifer Stettler Parsons, curator of “Flora/Fauna: The Naturalist Impulse in American Art,” notes. As an artifact, the cabinet spoke to her as the means by which to embark on an exhibition looking at artist/naturalists who have been committed to both realms since the founding of the United States.

The exhibition of 101 works, on view through September 17, draws primarily from the Florence Griswold Museum’s collection, augmenting them with selected loans from public and private collections. Many of the featured items were gifts of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. The inquiry begins in late Eighteenth Century Philadelphia, the site of the country’s first natural history museum.

After the American Revolution, natural history pioneers in and around Philadelphia set about documenting the country’s natural resources. Painter Charles Willson Peale established the Philadelphia Museum in 1786 for the study of natural history alongside art. Peale’s objective was to make wide-ranging collections democratically accessible.

If public appreciation for landscape drawing and natural history illustration had been cultivated by the steady stream of illustrated expedition reports produced originally for the British Royal Navy, it was the adoption of Carl Linnaeus’s binomial nomenclature that fueled the study of natural history by academics and amateurs alike. Having an interest in natural history was one thing, but being able to speak and write about the subject allowed naturalists from all walks of life to share their experiences and findings with others.

If public appreciation for landscape drawing and natural history illustration had been cultivated by the steady stream of illustrated expedition reports produced originally for the British Royal Navy, it was the adoption of Carl Linnaeus’s binomial nomenclature that fueled the study of natural history by academics and amateurs alike. Having an interest in natural history was one thing, but being able to speak and write about the subject allowed naturalists from all walks of life to share their experiences and findings with others.

Artists embraced America’s natural history as explorers, collectors, close observers, catalogers and early environmentalists. Among them were William Bartram, Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon, who “originated, developed and challenged notions of nature’s proper aesthetic representation, and then translated those concerns into fine art that could be enjoyed and consumed by a wider public,” Parsons writes.

By the mid-Nineteenth Century, artists sought to portray the American ethos in wilderness scenes, specifically in the Hudson River Valley and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. “Their resulting paintings symbolically linked the natural landscape to concepts of nationalism and environmentalism, equating the American landscape with American identity,” says Parsons.

It was an identity predicated in part on preservation, and on untouched land that was already threatened by the encroachment of rapid industrialization. Thomas Cole, in his “Course of Empire” series, struck a cautionary note, warning that “America’s passion for progress and industrialization could destroy the country’s most valued feature.”

Frederic Church, Cole’s only student, also embraced direct observation as essential to his art. He routinely sketched in oil and pencil while traveling the globe, then finished his pictures in his studio. Influenced by the writings of renowned German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, Church often began his monumental paintings with preparatory “vignettes of intricately observed natural details, rendered with scientific accuracy.”

Butterflies and moths from Willard L. Metcalf’s naturalist collection chest, circa 1885–1925. Mahogany wood drawer and specimens, 18 by 13¾ inches. Gift of Henriette A. Metcalf.

Charles de Wolf Brownell’s preference for creating on-the-spot sketches can be seen in studies marked with an “N'” in the upper left corners to designate that they had been made from nature. Martin Johnson Heade blended qualities of Hudson River School romanticism with scientific specimen illustration. He traveled repeatedly to South America, convinced that the only way to portray these creatures accurately was to observe them on native soil. Parsons notes that in his exacting canvases, Heade was moving from “the spiritual subjectivity of Emerson’s Transcendentalism toward the objective empiricism of Darwin’s theory of evolution.”

By the last quarter of the Nineteenth Century, American Pre-Raphaelites harkened to the English critic and artist John Ruskin’s call for visual art’s truth to nature. Mass marketed periodicals had opened up possibilities for nature illustrators such as Fidelia Bridges, and entire families were immersed in amateur nature studies as never before. A rare portfolio of Bridges’ watercolors, newly conserved, is on view for the first time here.

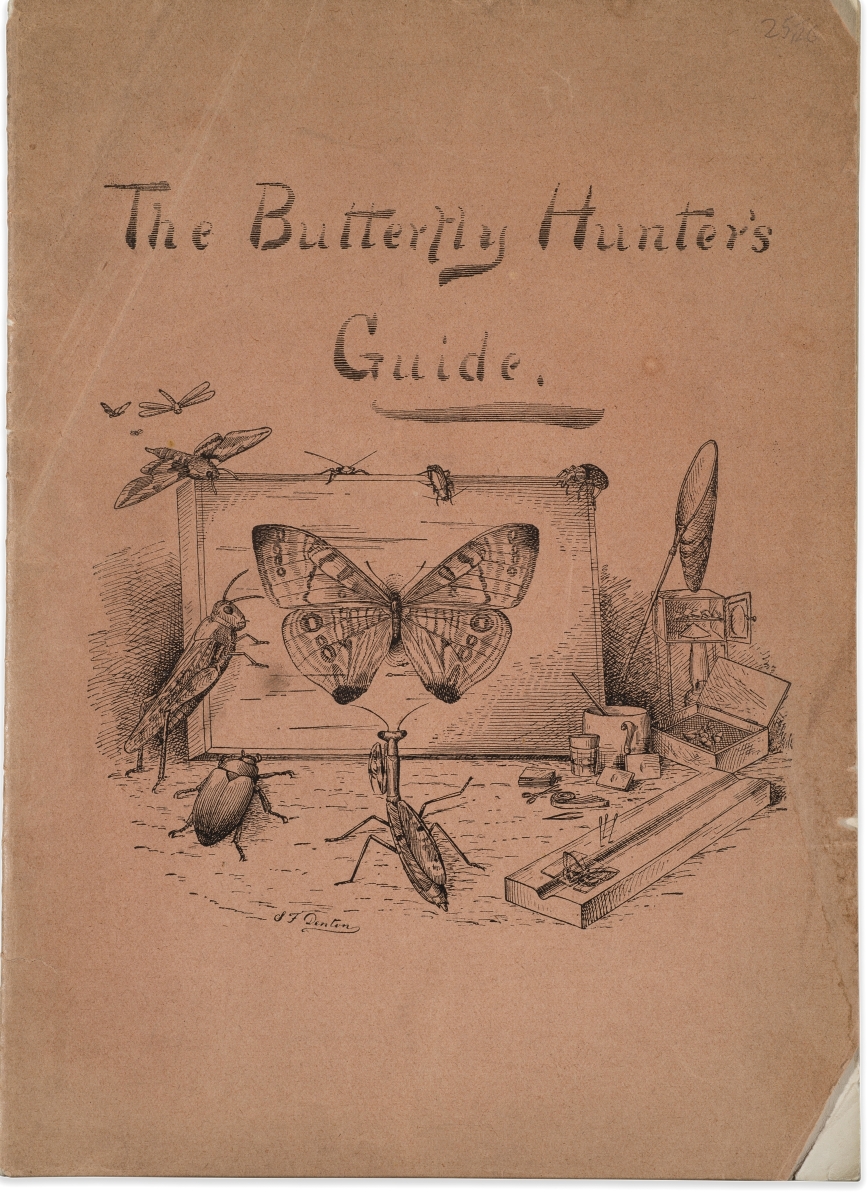

Geology, botany and/or entomology had become favorite pastimes. Indeed, “it was actually a challenge to find people who were not involved in some way with the collection of scientific specimens or the study of nature,” Elizabeth R. Fairman, editor of Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower: Artists’ Books and The Natural World, writes.

Butterfly collections, displayed on glass mounts produced by the enterprising Denton Brothers in Wellesley, Mass., were showcased as fine art alongside flower paintings and Japanese watercolors at the American Art Galleries in Manhattan. “The blurring of art and nature, the represented and the real, merits comparison with the Peale family’s exhibitions almost one hundred years earlier,” writes Ellery Foutch, who contributed an essay to the exhibition’s catalog.

“A Coral Cave” by Harry L. Hoffman (1871–1964), undated. Oil on canvas, 20 by 32 inches.

Gift of Carolyn Zeleny.

But in what would become a constant theme of push and pull, assaults on the environment were mounting. Theodore Roosevelt, encountering the decimation of bison, elk and bighorn sheep in the Badlands of North Dakota, became known as the “conservationist president,” successfully moving to protect approximately 230 million acres of public land.

At about the same time, the American Ornithologists’ Union estimated that five million birds were killed annually for the fashion market. Plumes, and even whole birds, were decorating the hair, hats and dresses of women. Ultimately, Roosevelt and other environmentalists passed legislation slowing the slaughter of native birds.

In the midst of these obviously polarized views of the use and value of nature, men, women and children routinely explored the countryside. They filled notebooks and diaries with sketches of rock formations and observations about birds and insects distinct to a region. Many had extensive curiosity collections, such as the one found in artist Willard Metcalf’s cabinet, which begins this show.

As Parsons delved into Metcalf’s life and work, she found he had been actively engaged in nature studies not only during his summers at Old Lyme, but during visits to Giverny, where he met French Impressionist Claude Monet. His knowledge of the natural sciences was such that Monet hired the artist to tutor his son and stepson. Metcalf continued to fill diaries and sketchbooks with meticulous notes and drawings, both in France and, later, as he explored the countryside as a member of the Old Lyme art colony. Art historian Bruce Chambers cited the cabinet as the key to Metcalf’s visual acuity as a plein-air artist finely attuned to the minutest details in nature.

In her catalog essay, Amy Kurtz Lansing observes that American Impressionists “favored sketch-like impressions of what the eye sees, and suggested with mosaic-like dashes of color intended to render ephemeral effects of light, shadow and atmosphere.”

While Childe Hassam sought to capture the rhythms of nature in Old Lyme and on the Isles of Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire, Harry L. Hoffman became entranced upon visits to the Bahamas with the idea of painting coral reefs “impressionistically, using broken colors of a light pink, green violet and blue, letting them thin out in the distance so that they merge into the disappearing iridescence.”

“Botany” by John Martin Tracy (1843–1893), 1891. Oil on canvas, 16 by 24 inches. Bequest of Arthur J. Phelan Jr.

From this point the exhibition leaps about 20 years hence to the life and work of longtime Old Lyme resident Roger Tory Peterson, whose A Field Guide to the Birds appeared in 1934 and became a standard kitchen-table reference for generations, selling more than two million copies. In addition to putting out a succession of nature guides, his art graced the covers of Audubon and Life magazines. Peterson lectured and traveled for much of the rest of his life. He is widely credited with working with Rachel Carson toward the ban of the pesticide DDT. From his field notes, he tracked not only the decline in the osprey population, but recorded that bitterns, kingfishers, night herons – whole colonies of fish-eating birds – were disappearing from the Connecticut River. Even the Bald Eagle was in serious trouble along the Atlantic Coast.

“Birds are far more than cardinals and jays to brighten the garden, ducks and grouse to fill the sportsman’s bag, or warblers and rare shorebirds to be ticked off on the birdwatcher’s checklist,” he said in a 1974 address to the Association for the Advancement of Science. “They are indicators of the environment – a sort of ecological litmus paper. Because of their furious pace of living and high rate of metabolism, they reflect subtle changes in the environment rather quickly; they warn us of things out of balance. It is inevitable that the intelligent person who watches birds becomes an environmentalist.”

In subsequent years, Peterson focused on gallery portraits of birds that sold well and were in considerable demand. Ultimately, he asserted, man “is the endangered species, and the extinction of a wild species is a milestone of a road marker of our own decline.”

Today, as the effects of climate change are being documented, Peterson’s words have come back to haunt us. Ice is melting at an alarming rate on the Antarctic shelf, coral reefs are dying, bird and fish populations are in significant decline, uninhabited islands are littered with detritus. Even beautiful Old Lyme is not immune. It is situated along the 41st parallel at what is anticipated to be a severely impacted zone of sea-level rise.

“We, alone of all creatures, have it within our power to ravage the world or make it a garden,” Peterson once wrote. One cannot leave “Flora/Fauna: The Artist and the Naturalist Impulse In American Art” without wondering which American impulse will win out.

The Florence Griswold Museum is at 96 Lyme Street. For more information, www.florencegriswoldmuseum.org or 860-434-5542.

The work of journalist Kristin Nord appears in publications throughout the United States and Canada.