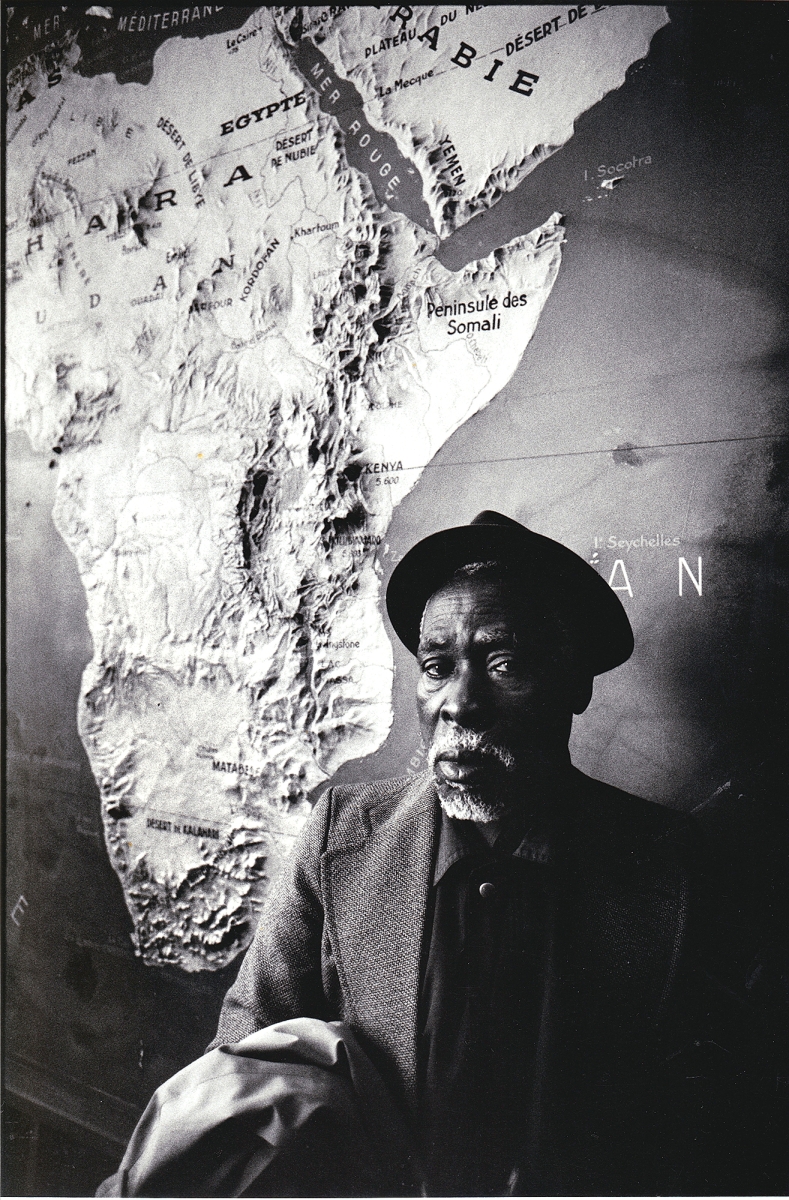

“Frédéric Bruly Bouabré at the Musée de l’Homme” by Philippe Bordas, Paris, 1993.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

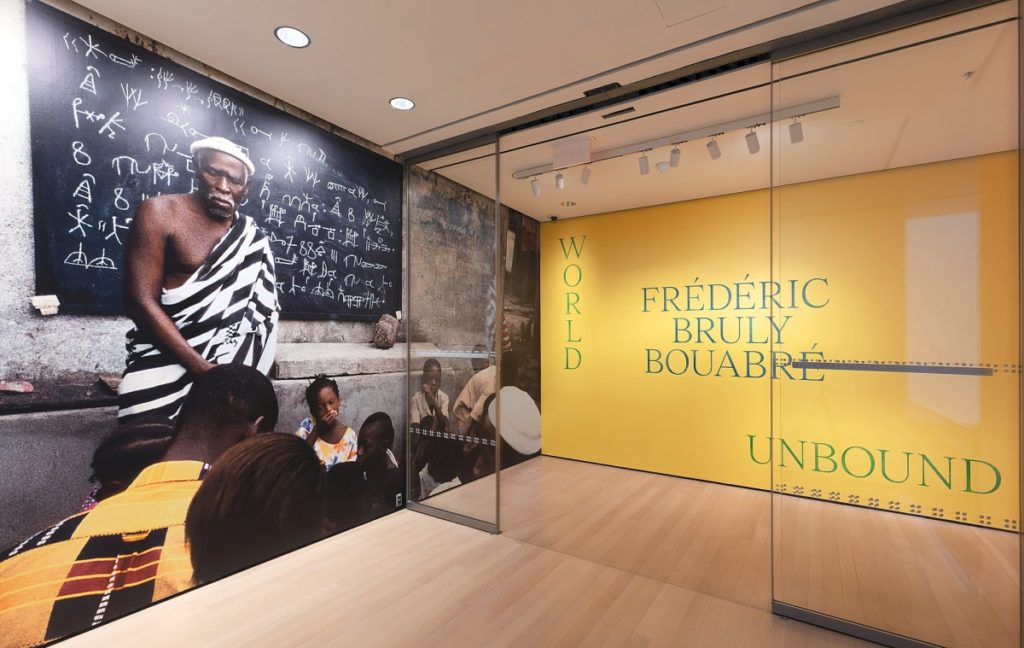

NEW YORK CITY – Artists’ retrospective exhibitions are frequently described as “encyclopedic” – covering every essential aspect of a lifelong body of work. “Frederic Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound,” the first comprehensive overview in the United States of Bouabré’s life and career, is certainly that, but it is also encyclopedic in another way. The artist’s very approach to his work was rooted in a desire to know and understand the world around him and to capture and record that understanding in word and image, often in book format. The fruits of Bouabré’s enduring encyclopedic project are revealed to visitors at “Frederic Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound,” at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) through August 13.

Frederic Bruly Bouabré is recognized overseas as one of the major figures in contemporary African art, but his name is little known to American audiences. His work was largely unrepresented in public American collections until collector Jean Pigozzi’s landmark gift to MoMA in 2019. Among the many works of African art in that gift were two complete series by Bouabré: “Alphabet Bété,” consisting of 449 individual drawings, and “Connaissance du Monde (Knowledge of the World),” comprising 30 drawings. The present exhibition is designed to do more than just celebrate that remarkable gift: with additional loans from the Centre Pompidou in Paris and numerous private collections overseas, including that of the Bouabré family, the show effectively introduces this essential artist to audiences in the United States.

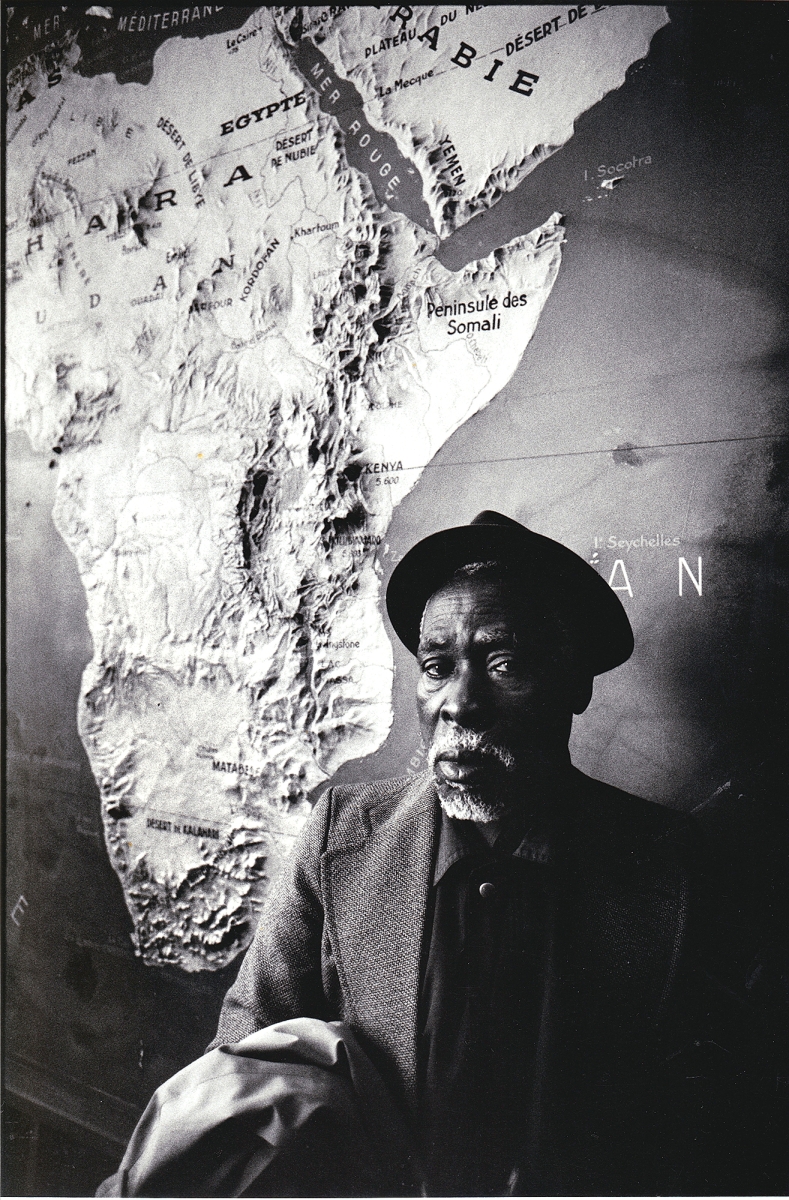

“GBRÉ=GBLÉ” N° 118” from the series “Alphabet Bété” by Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, 1991. Colored pencil, pencil and ballpoint pen on board. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art. ©2022 Family of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré.

Bouabré, who passed away in 2014, was a native of Côte d’Ivoire. He was born there in 1923, when much of West Africa was still under French colonial rule. Bouabré’s schooling and his voluntary service in the French West African Navy during World War II gave him his Gallicized name and fluency in French, but the local Bété culture to which he and his family belonged remained a touchstone for him throughout his life. Not long after the war, he began work for the French Ministry of the Interior in West Africa, effectively acting as a cultural attaché for the Bété community. The ministry’s goals, at least in part, were to understand the culture better to enhance the French colonial project, says exhibition curator Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi; it’s fair to assume that Bouabré was ambivalent at best about that. But it’s clear that the work’s aspect of cultural exchange, and of studying the culture to which he belonged, were of paramount interest to him. He took his work seriously, becoming a known and respected contributor (and a published author) in scholarly ethnographic and anthropological circles well before he was known as an artist.

One of Bouabré’s key ethnographic projects was the development of a Bété syllabary, a series of glyphs and pictograms that capture the purely spoken language of the community in which he was raised, a blend of Arab and Indigenous languages. The syllabary was initially inspired by the markings on pebbles known as “Békora stones” in the village of Gbékora, near where he was born. The source of the designs is unclear – even whether they are natural or human-made (and some believe them to be supernatural) – but Bouabré thought that they suggested an ancient form of script. The glyphs he eventually developed and codified evolved away from the stones, becoming more connected to contemporaneous aspects of Bété life, but the alphabet’s origins in the made world and the folklore of the Bété, from the tiny world of the pebbles to the cosmology they represent, was not forgotten.

“One of the beauties of Bouabré’s imagination is his ability to think through Bété, his culture, but also think in a very universal way,” says Nzewi. “The idea of the very local and the very global, it’s so central to the way he imagined his artistic practice.”

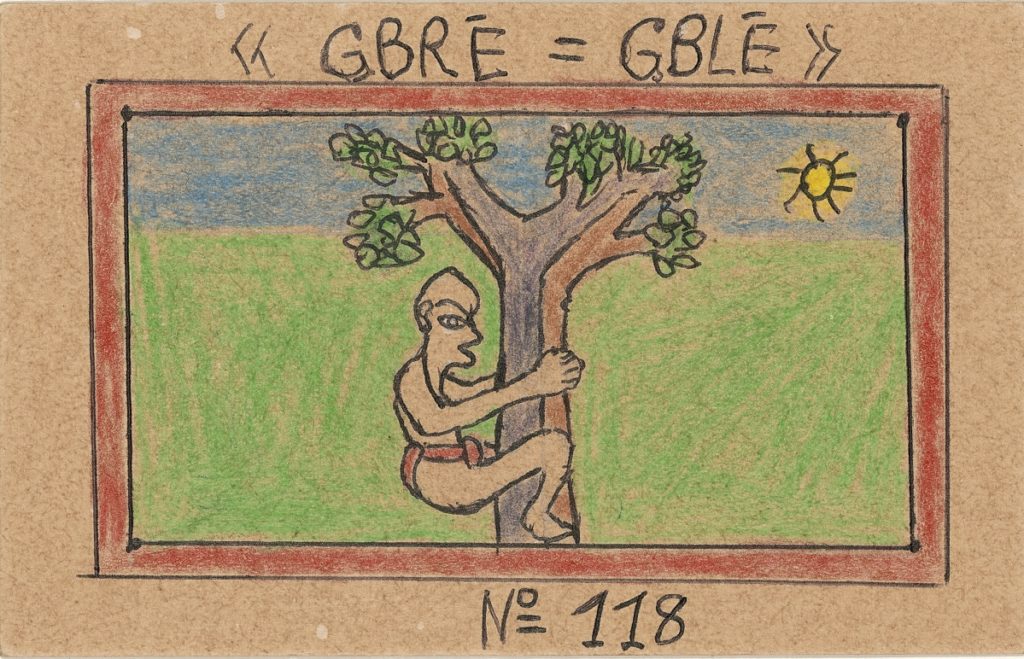

“Les pleurs de l’endeuillé se rendant aux funérailles d’un parent” from the series “Musée du Visage Africain,” by Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, 1996. Ballpoint pen and colored pencil on cardboard. The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art. ©2022 Family of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré.

The initial “Alphabet Bété” work was a formal piece of scholarship, first published in an academic journal in 1958, but it would reemerge later in his life as a major artistic project: the 449 drawings, made in 1990, now on the gallery walls at MoMA. Like the scholarly work, it blends word and image, but here the images come to the forefront. Each drawing, rendered in colored pencil and ballpoint pen on cardstock, depicts the central pictogram surrounded by a colored field and a contrasting border. Above is a phonetic pronunciation and below is a number reflecting its order in the syllabary; the script is careful and precise but also flowing and expressive. Confronted individually, the works have an undeniable graphic impact – frank and colorful line drawings of isolated things and concepts, ranging from vibrant fruits and verdant trees to murder, rendered in unforgiving tones of flesh and blood. Some are shockingly literal. To depict a foot, for instance, Bouabré shows it as if separated from its body, with a rosy circle indicating where it was once joined.

The “Alphabet Bété” occupies the first of two main galleries in the exhibition, where it is hung sequentially, in its entirety, on three walls. In that space visitors also have access to a digitized version of the syllabary, which adds audio to the blend of word and image. “One of the things we’ve tried to do is help our audience understand how important Bouabré’s writing system was and how he intended for the writing system to have a universal application,” Nzewi explains. “Visitors can match corresponding vowels of selected pictograms to either write short sentences or spell their name” and then hear them spoken aloud. A QR code system will allow them to save the results and take them with them after they leave the exhibition.

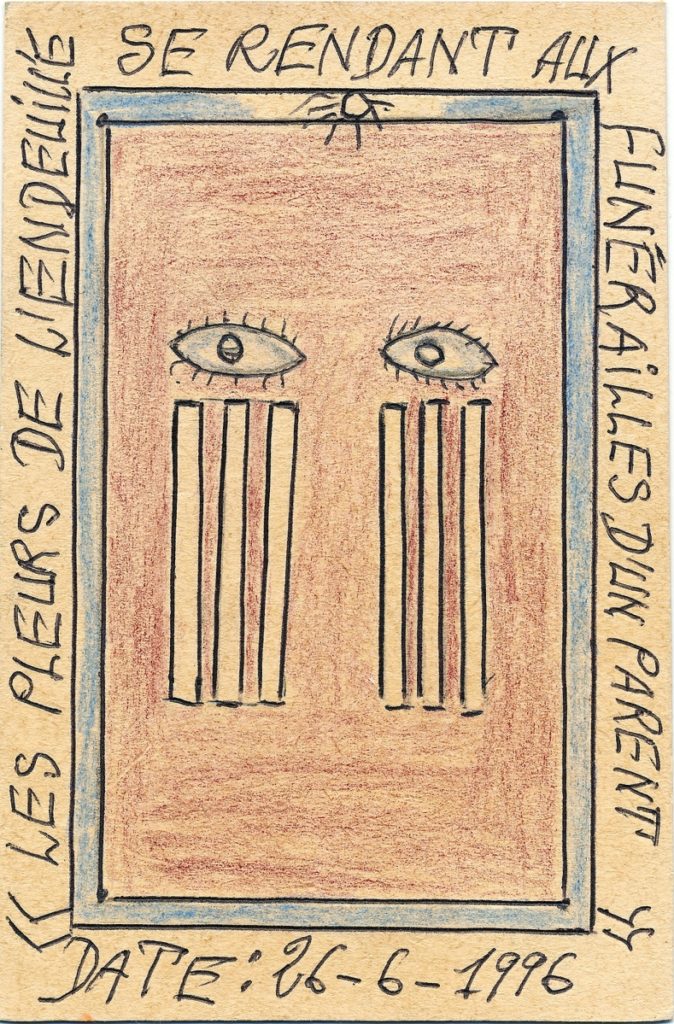

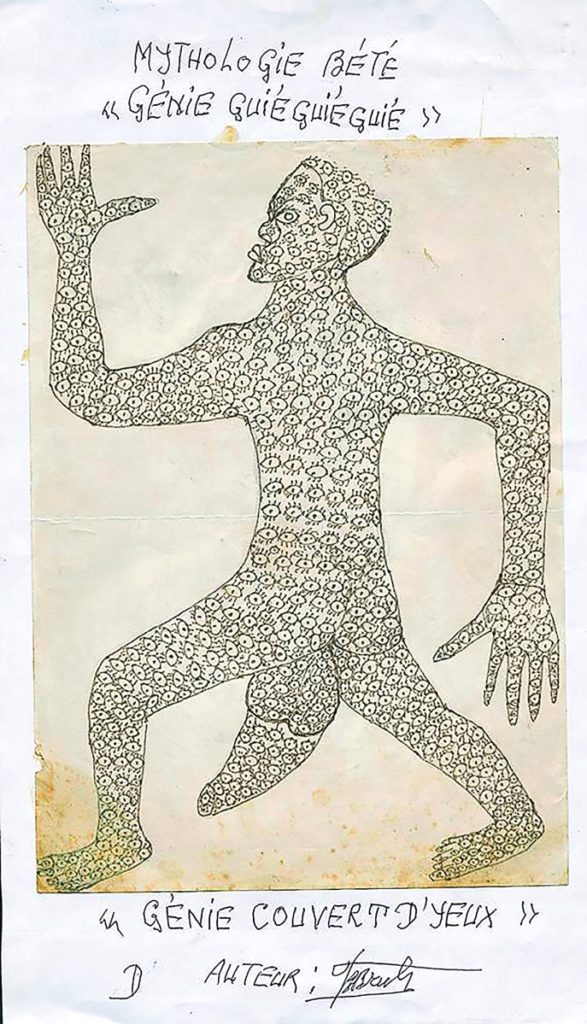

“Génie guié guié guié” / “Génie couvert d’yeux” from the series “Mythologie Bété” by Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, circa 1980. Ballpoint pen on laminated paper on cardboard. Private collection, Paris. Courtesy André Magnin. ©2022 Family of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré.

Much of Bouabré’s artwork was done in series like this, often rendered on the backs of cardboard inserts salvaged from the packaging for a specific hair care product popular in West Africa. The size is so small, and the shape so uniform, that it was a challenge, Nzewi confesses, to hang the show in a way that would keep the eye engaged. The solution was “to vary the framing of different series,” each according to its own distinct content and structure. The smaller “Connaissance du Monde” series, for instance, is hung salon-style, drawings stacked atop one another; while the “Musée du Visage Africain (Museum of the African Face),” which explores and documents traditional facial scarification patterns, is hung in pairs – one work showing the patterns on a face, the other an abstracted view of the patterns in isolation. Another series, “Hommage aux Femmes du Monde (Homage to the Women of the World),” which depicts women wrapped in the national flags of different nations – is framed in groups of about 50, stressing the idea of a global community and women’s essential role within it.

Having lived his entire life in a place where democracy was fragile, Bouabré was deeply engaged with and concerned about issues of self-governance. His series “Democracy: Signs of Equality” was made in 2010-11 in response to a recent election crisis in Côte d’Ivoire. “It is important for him to stress this international family of democracy, how important it is,” says Nzewi. “Of course, there is the backdrop of January 6 of last year, which in a way informed my choice of work for the show, but no one could have forecast that Ukraine was on the horizon,” he adds. “It’s important to see how very universal his thinking was.”

That sense of interconnectedness – across nations, across cultures and people, across time – is something that Bouabré became aware of in a spiritual sense when he was still quite young. As he remembered and retold it afterward, he was on his way to work at the ministry on March 11, 1948, when “the sky opened to my eyes and the seven colored suns described a circle of beauty around their ‘Mother-Sun.'” In that moment he adopted a new persona for himself – Cheik Nadro, the Revealer – and, as Nzewi writes in the exhibition catalog, “applied himself to a search for divine truths in nature and to the interpretation of his immediate surroundings and of the world at large.” His ethnographic work, which he continued for another 30-plus years, is thus inseparable from this revelation, which he later depicted in the eight-drawing series from 1991, “Vision Divine du 11 Mars 1948,” also in the present exhibition.

Installation view of “Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: World Unbound,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, on view through August 13, 2022. ©2022 The Museum of Modern Art. Robert Gerhardt photo.

An earlier work, from the 1981 series “Mythologie Bété (Bété Mythology)” also draws upon that vision, albeit in a less specific way. Titled “Génie Guié Guié Guié” or “Génie Couvert d’Yeux (Genie Covered with Eyes),” it depicts an isolated figure whose entire bodily surface – including hugely out-of-scale male genitalia – is encrusted with human eyes. Nzewi thinks of this as a kind of self-portrait of Bouabré qua artist, a kind of inveterate observer, a walking receptor of the visual. The emphasis on the testicles and phallus speak to Bouabré’s longstanding fascination with creation, procreation and the generative power of the natural world, also the subject of his 22-drawing series “Semance de la Vie (Seed of Life).” Completed in 1977, this is the earliest artwork by Bouabré in the exhibition. Showing “various scenes of copulation between man and woman, man and god, man and animal,” Nzewi notes, it “addresses the origins of life informed by Bété myths and belief systems but also Bouabré’s interest in and exposure to Christianity.”

Bouabré’s distinctive vision combined science and spirituality in a way that may seem uncomfortably seamless to many Americans. Nzewi, who is from West Africa himself (he was born and raised in Nigeria before attending graduate school in South Africa and the United States), laments that Bouabré and other self-taught African artists have not been as well received here as by other international audiences. Nzewi speculates, in his catalog essay, that a general overemphasis on the “primal or the uncanny” in Bouabré’s work has tended to overshadow how rigorous and formal his process really was. Bouabré himself said, “I do not work from my imagination… “I observe, and what I see delights me. And so, I want to imitate.” His careful renderings of West African facial scarification patterns, his observations of Békara stones, and, later, his meticulous recordings and revisionings of the natural patterns found on orange peels (“Relevés des Signes Observés sur Oranges,” 1989-2008) and kola nuts, along with the specific iconographies of Akan gold weights (“Poids Akan à Peser l’Or,” 1989-90) – these are not about interiorized religious experiences. They are about a knowledge of the world, a “connaissance du monde,” that is both minute and expansive – encyclopedic, if you will. The almost invariable inclusion of the written world underscores that drive to attain, record and preserve knowledge, in the deepest sense of the world. “Writing is what immortalizes,” Bouabré said. “Writing fights against forgetting.”

The encyclopedic project that is this exhibition echoes Bouabré’s own comprehensive approach to knowing and understanding the world. The exhibition includes many of Bouabré’s bound manuscripts, created both before and after he retired from the civil service and dedicated himself professionally to art, along with ephemeral objects that find a manifestation in his artwork: Darling brand hair care packaging, Akan gold weights, Békara stones. Numerous photographs also document how truly international Bouabré was as a scholar and an artist: here he is at the Pompidou in 1989, at Dia Art Foundation in New York in 1994; here is his work at more than one Venice Biennale. “I wanted the audience to really understand the wholeness of the artist,” Nzewi says. “For you to understand his drawings, for you to understand his writing, you have to understand the entire universe that he operated in.”

The Museum of Modern Art is at 11 West 53rd Street. For information, 212-708-9400 or www.moma.org.