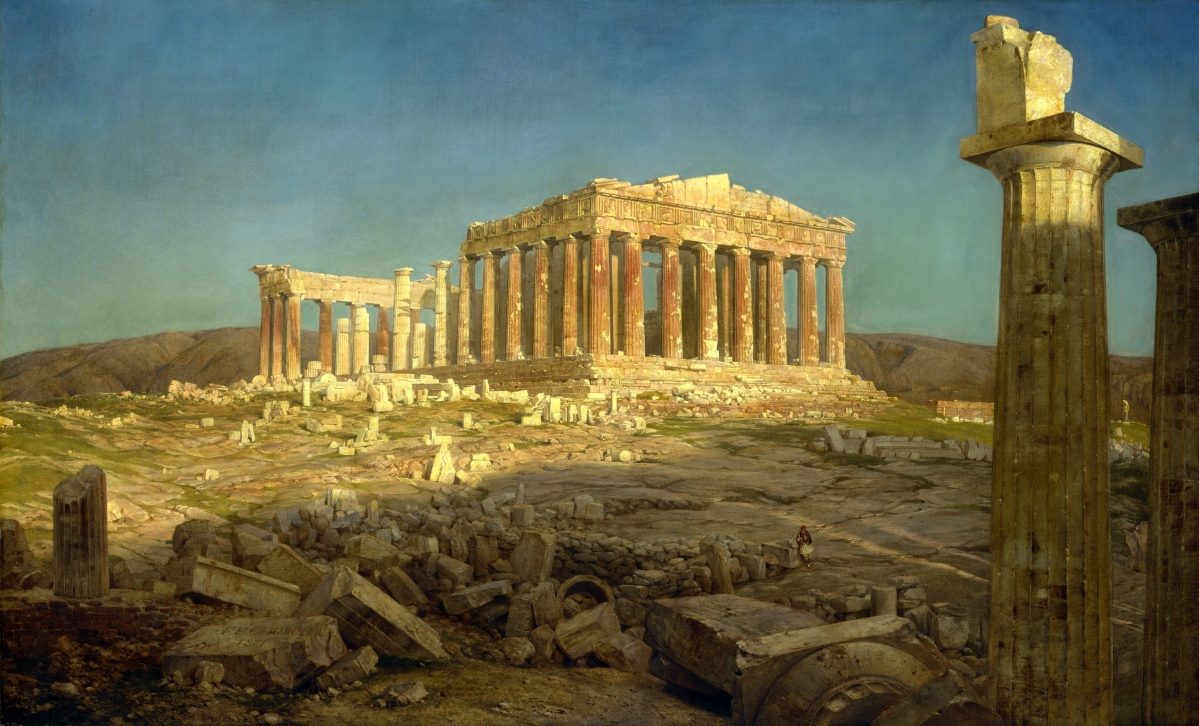

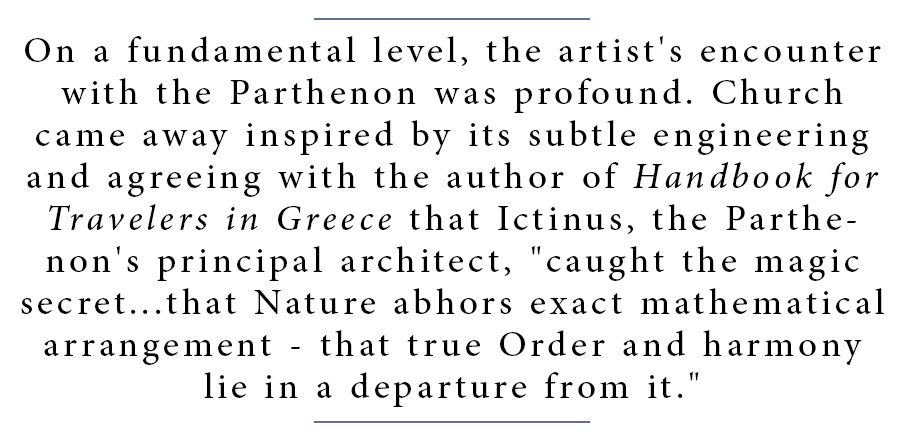

“The Parthenon,” 1871. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Maria DeWitt Jesup, from the collection of her husband, Morris K. Jesup.

By Kristin Nord

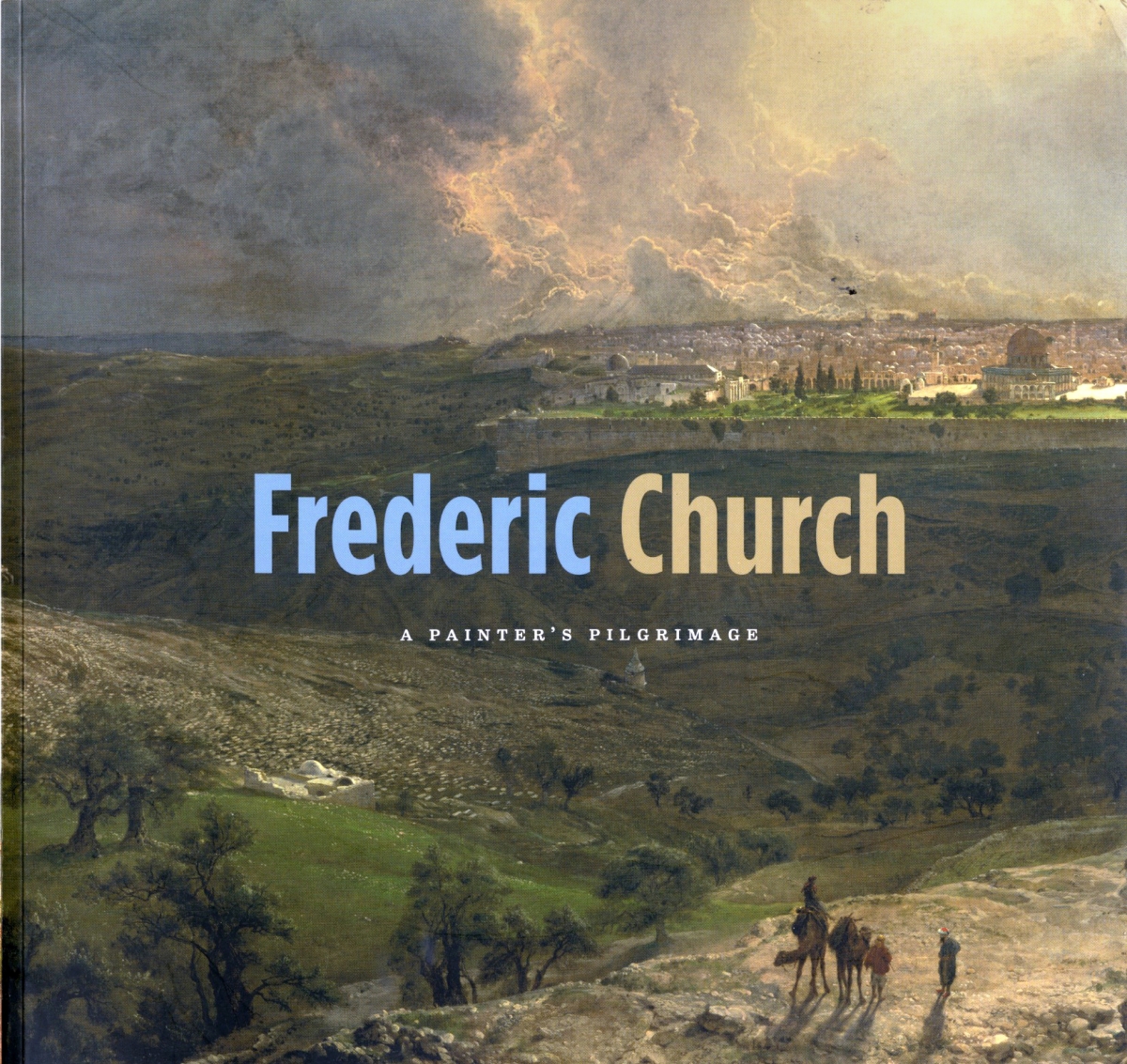

HARTFORD, CONN. – He followed the routes of the great naturalist Alexander von Humboldt to capture spectacular scenery in diverse and exotic locales. Now, on this trip to the Holy Lands, Frederic Church (1826-1900) intended to shift his lens to the man-made remnants of a great civilization and to capture pivotal sites from the Bible. To prepare, he spent time studying architecture and honing his drafting skills in an architectural office. He was armed with the latest travel guides and scholarly biblical material. Primed like an athlete, he boarded the steamer Europe in November of 1867 with his wife, Isabel, son and mother-in-law, bound for the eastern Mediterranean.

In today’s culture, where church attendance in mainstream Protestant denominations is declining, it is a revelation to go back to the mid-1860s, when families were regular churchgoers, able to recite chapter and verse from their illustrated parlor Bibles. Church, a Hartford native, was descended from Puritan stock and christened in Center Church, across from the Wadsworth Atheneum. When he left the city as a young man to study with the great Hudson River painter Thomas Cole, his mother wrote to remind him, “The eyes of a pure and holy God are upon you.”

The wider world brought Church into the company of more liberal Protestants, notably the Reverend George Bethune, an accomplished classical scholar and pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church in Brooklyn, N.Y. With shared interests in science, innovation, archeology and the visual arts, the two men became fast friends. Church was heading into the Holy Land fully conversant with the important miracles in the Old and New Testaments, but, like Bethune, able to experience these stories metaphorically, says Kenneth Myers, curator of American art at the Detroit Institute of Arts and the vision behind “Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage,” at the Wadsworth Atheneum from June 2 to August 26.

This trip had both personal and potentially mercantile aspects. Church and his wife were devastated by the deaths of two children from diphtheria just a week apart in 1865. Grief-stricken, the couple repaired for two months to Jamaica, where Church ultimately produced a very dark landscape, seemingly at odds with the emerging light.

At the same time, Church, who had been the most successful of the Hudson River School painters, was cognizant that his popularity was waning. The softer Barbizon style of artist George Inness had become popular, and art collectors were exhibiting renewed interest in the human figure. According to the art historian Gerald Carr, who contributed to Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage, the catalog accompanying the exhibition, “The question for Church, on the verge of his trip to the Mediterranean, was whether or not he could reposition himself as a painter of Old World artifact-based allegories, one who was conversant with scripture, archaeology, travel and romance literature, and both traditional and recent European-American landscape and figure painting. Many believed he could; others, though, were dubious, and said so.”

At the same time, Church, who had been the most successful of the Hudson River School painters, was cognizant that his popularity was waning. The softer Barbizon style of artist George Inness had become popular, and art collectors were exhibiting renewed interest in the human figure. According to the art historian Gerald Carr, who contributed to Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage, the catalog accompanying the exhibition, “The question for Church, on the verge of his trip to the Mediterranean, was whether or not he could reposition himself as a painter of Old World artifact-based allegories, one who was conversant with scripture, archaeology, travel and romance literature, and both traditional and recent European-American landscape and figure painting. Many believed he could; others, though, were dubious, and said so.”

Political reforms and expanded steamboat services to the region had paved the way for visitors, setting off a flurry of missionary and religious activities. Soon American tourists were flocking to the Holy Land as well. If traveling dioramas had offered paying customers simulated pilgrimages to Palestine via massive scrolls, now a paying public wanted the actual experience. Palestine loomed, as Dr William M. Thomson, a founder of the Syrian Protestant College in Beirut expressed it, as “the divinely prepared tablet whereupon God’s messages to men have been graven in ever-living characters by the Great Publisher of Glad Tidings.” Other artists from England, France and the United States were conjuring exotic scenes, and Church would soon add his name to the list.

The Church family set forth, aware that there could be some danger involved. Overland transportation was dependent on camels, donkeys and horses. The threat of bandits was real. Roads, where they existed, were poor. Just two years earlier, the Ottoman grand vizier, Fuad Pasha, had declared: “I shall never concede to these crazy Christians any road improvement in Palestine, as they would then transform Jerusalem into a Christian madhouse.”

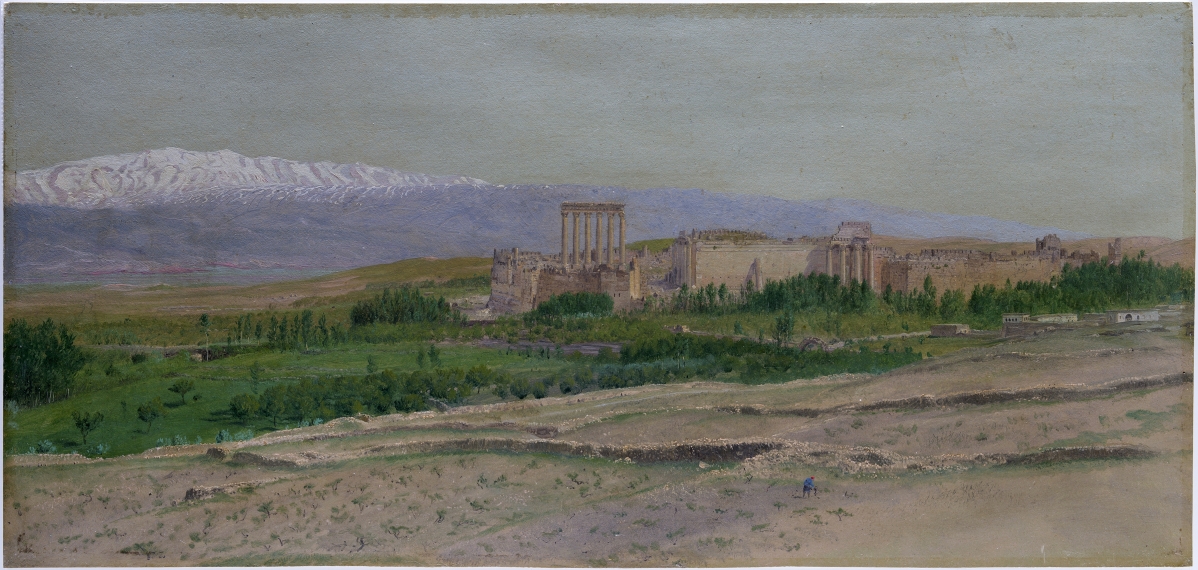

Isabel accompanied her husband on sketching trips to Egypt, Damascus and Baalbek, but by February of 1869, after she gave birth to a son, was ensconced in Rome surrounded by American friends. Church went on to complete major paintings focusing on key sites he toured in the Ottoman province of Syria, as well as in the Mediterranean.

Like many devout Christians of the time, the Churches did not work on the Sabbath, instead devoting the day to Bible study and to prayer. Among their memorable stops was the Mount of Olives, where they camped with friends, staying in tents and reading specific passages from the New Testament. While Isabel recorded what for her was a tremendously moving experience, Church’s response, “Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives,” 1870, became the most widely promoted and discussed painting of the trip.

Between 1868 and the end of his career, Church produced between 25 and 30 paintings on Old World subjects, all but five of which were idealized compositions. In addition to “Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives,” the largest and most important were “Syria by the Sea,” 1873; “The Aegean Sea,” 1877; “Damascus,” 1869, destroyed 1888; “The Mountains of Edom,” 1870; and “The Parthenon,” 1871. These paintings generally focused on classical ruins, with diminutive figures attired in then-contemporary Middle Eastern dress placed in the foreground. If visually they seem to suggest the sequential rise and fall of human civilizations, Myers writes, “Ultimately our attention is drawn outward and upward; we pass from the shadow of death and bask in the warm glow of what one period viewer described as ‘the golden glory of an Eastern sunset.'”

Critics would fault the overarching attention to detail of these later works, but Myers reminds us that Church’s Holy Land paintings were addressed to the Christian faithful and came “preloaded with meaning that his intended audience already knew.” For this audience, as a Home Journal reviewer correctly predicted, “‘Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives’ will be a veritable revelation, lifting, as it were, the veil that threatened to hide forever from their eyes the vision of their hearts’ true home on earth.”

Major works for this traveling exhibition are on loan from the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Erin Monroe, the Wadsworth’s associate curator of American paintings and sculpture, installed galleries in such a fashion as to offer visitors a pilgrimage as well. The Wadsworth has a renowned permanent collection of Hudson River School holdings that include Church paintings of note, among them the artist’s first major history painting, “Reverend Thomas Hooker and Company Journeying through the Wilderness from Plymouth to Hartford, in 1636,” 1846, which helps document the story of Connecticut Protestantism and which anticipated Church’s interest in the idea of pilgrimage. Church was not alone in making such pilgrimages. Mark Twain later skewered such journeys in The Innocents Abroad. An Arabic New Testament that Twain brought home from his travels is included in the show.

Because Church’s estate, Olana, in Hudson, N.Y., is within easy driving range, staff are collaborating on day trips between these two sites this summer. Olana has organized an exhibition, “Costume & Custom: Middle Eastern Threads at Olana,” showcasing textiles Church brought back from the Holy Land, some of which figure in his paintings.

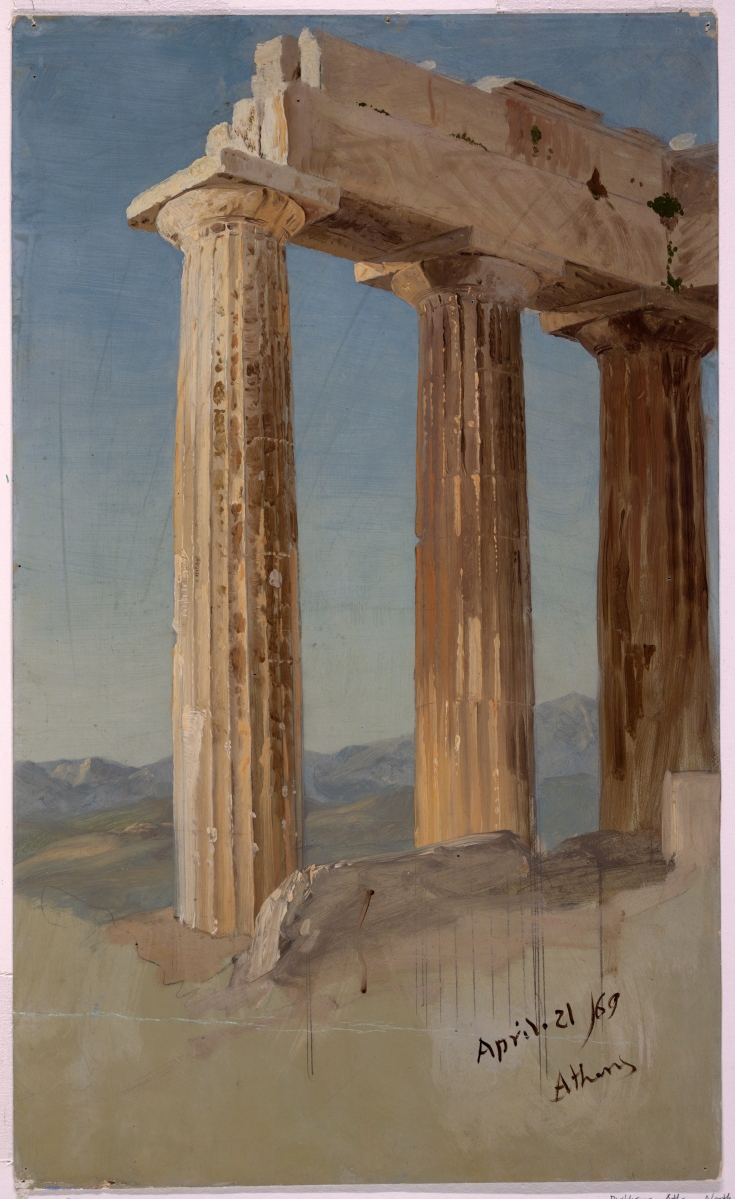

On a fundamental level, the artist’s encounter with the Parthenon was profound. Church came away inspired by its subtle engineering and agreeing with the author of Handbook for Travelers in Greece that Ictinus, the Parthenon’s principal architect, “caught the magic secret…that Nature abhors exact mathematical arrangement – that true Order and harmony lie in a departure from it.”

Church made 30 known sketches of columns, ornaments, moldings and fragments. He also sent home marble remnants from the Acropolis, at least one of them a chunk of column with flute carving. These served as models when he began his “great picture,” “The Parthenon,” 1879.

Today, however, it is not this painting, impressive for its exactitude, that suggests all that Church absorbed. It is his Olana, a créme brûlée marvel of Gothic Revival, Italian Villa, French Mansard and Ruskinian Venetian architecture brimming with Islamic motifs and artifacts. The house casts a spell. Glistening stencils Church based on Persian patterns adorn the walls. Just as the Parthenon was constructed from stone from nearby Mount Pentelicus, Olana’s stone was locally quarried. And, as much as the southeast of the Parthenon overlooks the Straits of Salamis and the island mountains, Olana’s south-facing sitting room frames a view of the Hudson River and the foothills of the Catskills beyond. Taken together, the property and what Church called his “feudal castle” became a living, breathing entity, affording spectacular views from every vantage point. It is not hard to imagine the elder Churches in rocking chairs, surveying this man-made and natural masterpiece when their work was done.

The Wadsworth Atheneum is the final stop for “Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage,” which opened at the Detroit Institute of Arts and traveled to Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, N.C.

The Wadsworth Atheneum is at 600 Main Street. For more information, 860-278-2670 or www.thewadsworth.org.

Journalist Kristin Nord divides her time between Connecticut and Nova Scotia