“Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as Tehuana)” by Frida Kahlo, 1943. ©2016 Banco de Mèxico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and the INBA.

By James D. Balestrieri

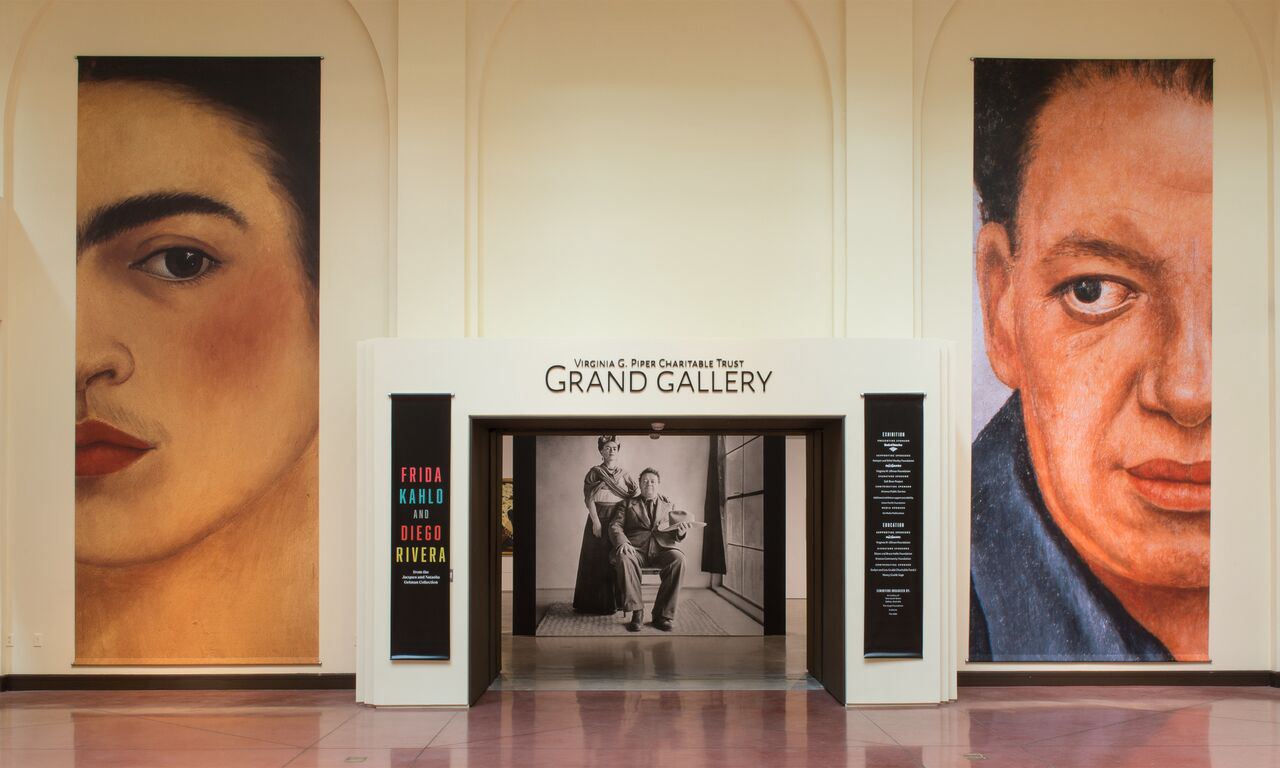

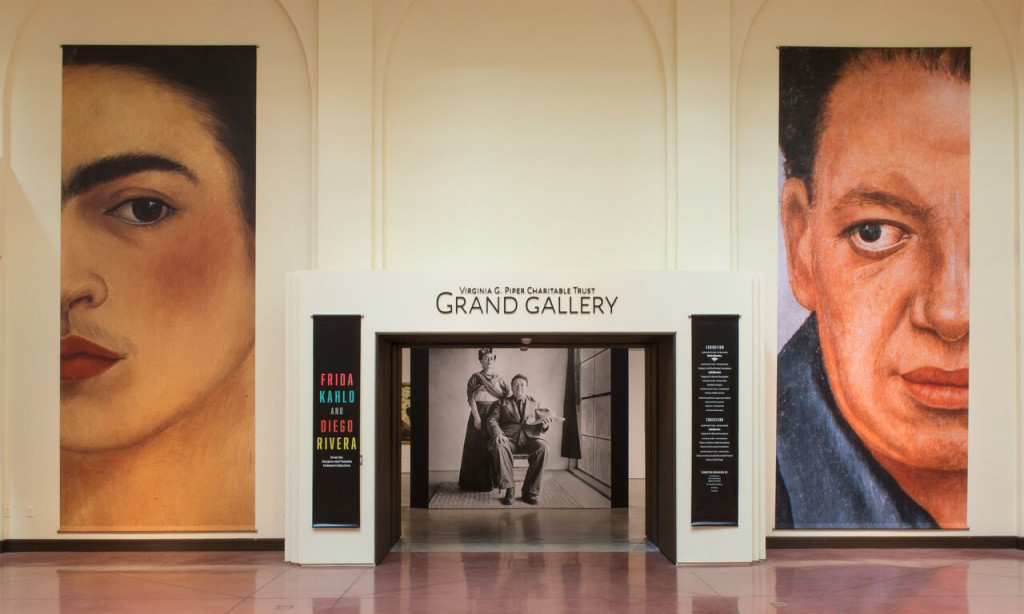

PHOENIX — In “Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera,” the coup scored by the Heard Museum — the Heard is the only North American stop for this outstanding exhibition of works from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman collection — the paintings dazzle, as one would expect. But having been fortunate enough to be in Phoenix and to have been invited to the opening at the Heard, in retrospect I believe it was one of the many revelatory photographs that sizzled, that crackled like dust on a romantic corrido spinning in 78 rpm and that added new pieces onto the unsolvable puzzle that is Frida and Diego.

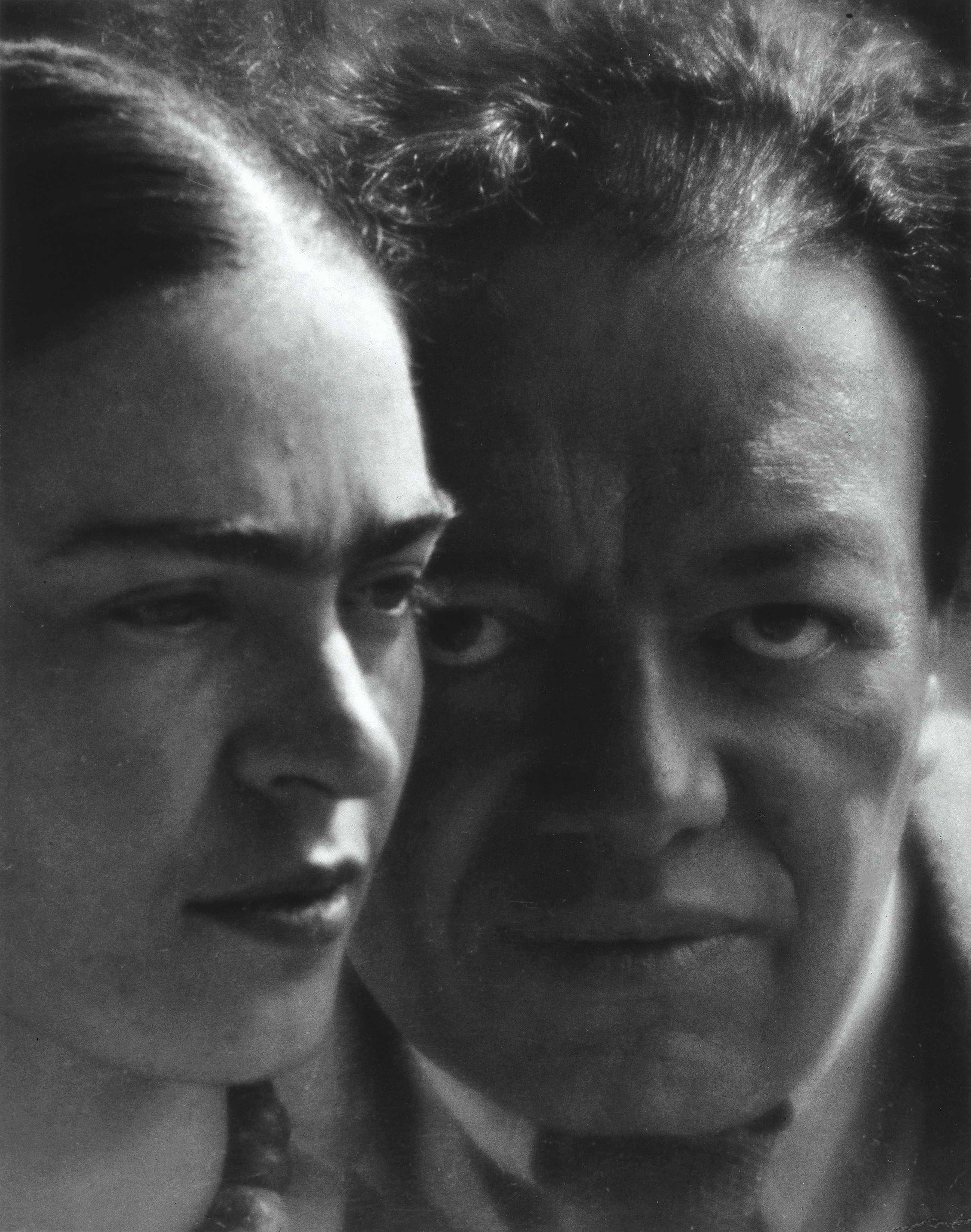

In two different photographs Rivera stands behind Kahlo. She is seated at her easel, painting. Rivera’s hands hold the back of her chair. Rivera — a giant in life and in the heroic, public art of Mexico in the Twentieth Century — towers over Kahlo, over her diminutive form, wracked with the physical pain she suffered for the rest of her life after breaking her back in a bus accident. Against his larger-than-life life and career, Kahlo’s 53 paintings, virtually all of them relatively self-portraits, seem small. And yet, all I could think as I looked at Rivera, in these — posed? — photos, is that, for all of his bulk and fame, rather than holding Kahlo down, he’s hanging onto the back of her chair for dear life as it is about to blast off into orbit.

“Diego on my mind (Self-portrait as Tehuana),” 1943. In one of the two photos, Kahlo is working on this very painting — you can turn a corner in the exhibition and see it for yourself, in the paint. It is an experience I highly recommend.

Kahlo’s forehead on the canvas becomes a mirror for the man, Rivera, standing behind her. But he is small in that mirror, only a part of her mind, smaller physically than she is. Painting him here, this way, brings him — as a source of inspiration and a haunting ghost — to the surface of her face, of the painting. At the same time, this act diminishes him, contains him, dwarfs him even as she herself, through the tangle of wires, lines and vines, connects to the edge of the canvas, the edge of the artist’s universe, becoming an electric, generative force of nature, yang to Rivera’s yin. Rivera watches Kahlo do this, and, amazingly, he lets someone photograph him watching her do this.

The painting itself, “Diego on my mind,” is perhaps the most striking work in the exhibition. Apart from the filaments of vitality and energy, Kahlo’s choice of the Tehuana “Vela” party dress, from the Tehuantapec region in the south of Mexico, points to the matriarchal society of the Tehuana; it is a direct reproach to Rivera’s machismo and devastating extramarital affairs. Beyond that, in this painting Kahlo portrays herself as a disembodied face, surrounded by lace against a gilded background. She is almost a Byzantine Madonna, divine, disembodied and out of reach.

Where Frida Kahlo makes herself surreal, even hyperreal, Rivera’s works in the exhibition cast the world in a surreal and hypersensual light. Under the lush yellow petals and the watchful seeded eyes in “Sunflowers,” a girl looks down at a broken doll (while another doll sits, ignored, under a nodding blossom) while a boy contemplates a spectral clown mask (while another bird mask stares up from the earth). Nature seems to be watching the pair grow up, injuring one another inadvertently, taking on new personae.

Behind a profusion of frankly sexual cut calla lilies in “Calla Lily Vendor,” a man’s sombrero and hands are the only signs that betray his presence. Who is the vendor? The unseen man? Or the two kneeling women? And are they sisters or a single woman at two different moments? If he is the singular seller, why is one of the women wrapping a thick ribbon around the basket? The ambiguities lead down any number of paths, all at once.

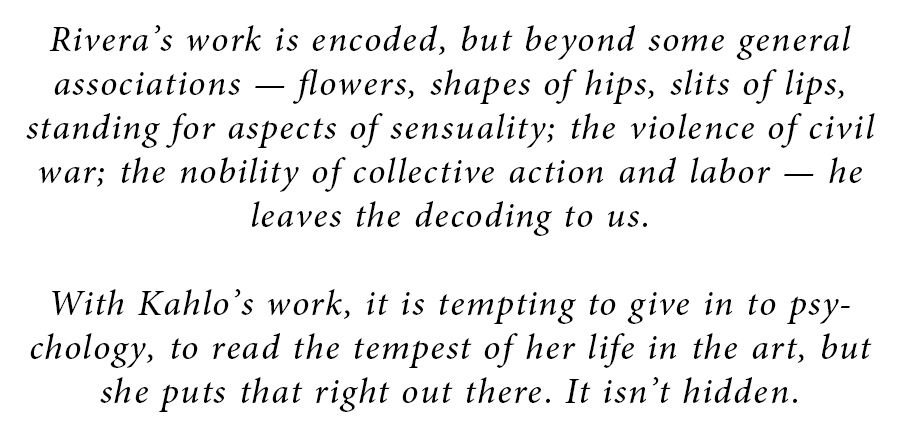

Rivera’s work is encoded, but beyond some general associations — flowers, shapes of hips, slits of lips, standing for aspects of sensuality; the violence of civil war; the nobility of collective action and labor — he leaves the decoding to us.

With Kahlo’s work, it is tempting to give in to psychology, to read the tempest of her life in the art, but she puts that right out there. It isn’t hidden. It isn’t coded. But perhaps to read the tempest of her life into her paintings does her a disservice. Perhaps we should think of her self-portraiture as we do Rembrandt’s. Or perhaps we should think of her portraits, her selves (proto-selfies?) as we think of Monet’s haystacks or water lilies, or Morandi’s still lifes in shades of white, as approaches to pictorial problems, recording moods and impressions as we perceive the effects of light and shadow across landscapes, or the sea. To impart specific meaning — feminist these days — to her mustache or unibrow, or to her clothing — indigenous, adopted, appropriated — as she, of course, had no indigenous blood in her, is perhaps to diminish her, to turn her into a back projection of our own preoccupations and fantasies, to demystify her as we insist on seeing Kahlo the person instead of, in place of, the paintings of her, painted by her.

After all, Frida Kahlo was Mexican, but of German and Spanish heritage. The exhibition, complemented by examples of the indigenous dresses and accents she adopted, ask the question: what would we say today of her appropriations, even as so many women — dozens alone at the opening — revere and style themselves after her fashion, which was not fashion to her, but part of the very fabric of her being? How would we respond to an American artist of, say Dutch and English heritage, sporting a headdress from a tribe she did not belong to, even if she wore it in solidarity with that tribe? Would we accept it?

We focus on what Kahlo’s paintings reveal about her. But what do they hide?

It is worth going behind the mythology that swirls around the lives of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, behind their marriage, their affairs, divorce and remarriage, behind their associations with some of the great figures of Twentieth Century art and left wing politics: Josephine Baker, Leon Trotsky, Pablo Picasso, behind the story of Rivera’s commission to paint the murals in Rockefeller Center and how he lost the commission because he painted Laurence Rockefeller into the mural as a tycoon surrounded by whores.

Rivera and Kahlo are identified with the Mexican Revolution and with socialism in the early Twentieth Century, yet neither was really there as a participant or eyewitness. Kahlo, born in 1910, was too young, while Rivera was away during the Villa and Zapata years, in Paris, studying and emulating Picasso. Even World War I, so near at hand, seems not to have touched him personally. Rivera’s paintings in this period, though replete with Mexican folk elements and symbols of the peasant revolution, are Cubist assemblages, Picasso-esque and Braque-like. Rivera railed against Picasso, claimed that Picasso was copying him, but in the photograph I imagine, he stands behind Picasso as he stands behind Kahlo, holding his chair, though more in the manner of a waiter.

“Sunflowers” by Diego Rivera, 1943. ©2016 Banco de Mèxico Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and the INBA.

When he returned to Mexico after the revolution and was put in charge of public art, he adapted classical bas-relief style, filling the picture plane with overlapping figures in shallow spaces, presented in a limited palette (it must be said that Rivera’s late style owes a debt to Picasso’s earlier, turn-of-the-century figurative work). Rivera’s monumental public works, as well as those he oversaw, validate the revolution in Mexico. Sadly, they end up as propaganda propping up and seeming to apologize for what became an anti-democratic, quasi-military regime. As a point of comparison, look at Orozco’s murals. Orozco, who bore witness to the horrors and atrocities of the revolution, makes us confront the violence clear-eyed, without flinching, and without the comfort of revolutionary ideology. He is ambivalent about its aims and uncertain about its outcome. As are we.

Though she shared Rivera’s socialist fervor, Kahlo’s art is more concerned with capturing the flicker film of interiorities that shape a person and that person’s persona. She may be in the world, a woman of the world, but the world is also — a priori — in her, expressed in the lines and planes and shapes of her face, which become, in her paintings, signs — at best — of the real person beneath. Each of her self-portraits becomes a mask, projecting haughty confidence, wounded vulnerability, severity (as in “Self-portrait with Necklace”), bemusement (as in “Self-portrait with Monkeys”) or all of these at once.

Diego might have been on Frida’s mind, but he was never all that was on her mind. Kahlo’s ultimate elusiveness — from Rivera and from us — is what makes her work so fully human, so revolutionary and so utterly arresting.

“Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera” is on view through August 20.

The Heard Museum at 2301 North Central Avenue. For information, www.heard.org or 602-252-8840.

Jim Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City. A playwright and author, he writes frequently about the arts.