Wacht hopped off the podium to show off the original painting on the side of this spool cabinet. It had an inkwell on the lift top and the painting on the side featured an eagle. It sold for $320.

Review and Photos by Greg Smith

CANTON, CONN. – Richard Wacht looked out from his raised perch over the gallery before him on July 27 and saw every seat – all 350 of them – filled with a bidder sitting on a worn cushion, the benches that ran the full length up the sides of the gallery packed full with touching knees, and a considerable remainder of people standing along the back wall. All were eagerly, if not regrettably, waiting for the opening note of the swan song to begin. Canton Barn – the business his father John Wacht started in the 1940s and he continued to run with Susan Goralski through that evening – would hold its final sale that night. Retirement had arrived.

Wacht, now 77, was not a modern-day auctioneer. That feeling of straight-faced, common sense, old world business acumen is what undoubtedly endeared him to his loyal group of bidders, many of whom attended his sales regularly. Some elements of his auction process retired in the business long before he did. “I don’t go to other auctions,” Wacht told Antiques and The Arts Weekly. “So I don’t know how they do things.”

There was no buyer’s premium at a Canton Barn auction, simply because Wacht did not agree with the principle.

“It didn’t sound right to me,” he said. “To charge a person because they’re buying something? They’re coming, supporting your business and they’re buying things and yet you’re charging them for doing it? It never sat well with me.”

As bidders today get caught in the moment, struggling with the mental hipshot math with every incremental bid that raises the true cost of antiques at auction for the buyer, Wacht made the equation as simple as it could possibly be: hammer price plus tax, the latter an inescapable certainty of life.

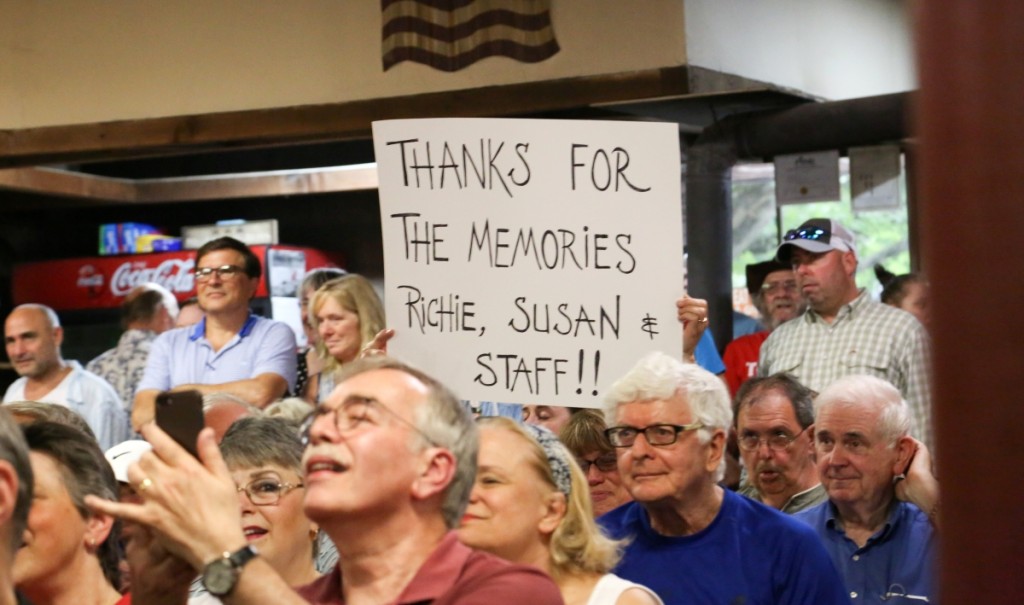

The crowd packed into the barn for Wacht’s final sale. More than 350 people filled every square inch of the gallery to try their hand at bidding one last time.

And there were no bid cards. Two runners would stand next to the cashier desk writing down Wacht’s description of the item as it rolled off his tongue, noting the hammer price when it sold, and if they knew the buyer from previous sales, their name. If they did not know the buyer’s name, they would come off the stage and ask for it. Rinse, repeat, the whole night through. “If we didn’t know who you were, the runner would go down to get your name. The next item you buy, the runner will know your name. So it worked,” Wacht said.

Wacht also owned every single thing he sold – and sold them without reserve. We asked him how this was possible, how he could run every week, sometimes twice a week (until last year when he brought his sale frequency down to every other week) without consignments.

“A lot of it came from private people,” Wacht said. “I would buy two or three estates from them. First the uncle would pass away, and then the mother. It all came funneling in from down the road like that.

“The stuff is drying up, though. You don’t get the attics filled with great stuff anymore. The homes are rebuilt and the attics insulated. It was easier years ago because there was more stuff on the market.”

It also begged the question: how many things has Richard Wacht owned in his lifetime?

An approximation puts that number north of 500,000 individual items, a jaw-dropping figure. Richard Wacht has left an indelible mark on the business.

Wacht’s interest in antiques began in much the same fashion as many of his peers, through growing up with antiques in an old colonial home. “They were always there, and my father always dealt with them, it’s what I liked,” he said.

His father John Wacht started running the auction house in the 1940s. Richard grew up working with his father and the family together would run onsite auctions under two large three-pole tents that were decommissioned from the US government. “We lost them both in the hurricane of ’55,” Wacht said. “They were set up at homes, and they just got shredded.”

A regular at the sale held up this “Thanks for the memories Richie, Susan & Staff” sign before the sale got underway.

The business carried on without them, but Wacht’s father became sick with Leukemia contracted from asbestos exposure during his time in World War II. In the 1960s at the age of 15, Wacht started to take over responsibilities from his father. “That includes bidding on the house, buying it, moving it and everything,” Wacht said.

At the outset, the names of items were passed down through handling them and Wacht was able to learn them by appearance. “The names of a lot of glass and china, for some reason I had the ability to remember them,” Wacht said. “A lot of dealers would stop in on a Sunday and they would ask me what things are called. They didn’t care if I knew what it was worth, what they wanted me to do was tell them what it is so they can look it up.”

In the 1960s, the sales moved into the auction barn where they have been held since. In fact, almost everything remained unchanged to date, including Wacht’s responsibilities. It was him, up until July 27, who would bid the house, clear it of its contents, haul the furniture over the front lawn to the truck, load it up and take it to the gallery, where he would sit at the podium and sell it off. Every week, 46 weeks a year, since he was 15 years old.

Wacht’s former wife of nearly 30 years, Susan Goralski, was in charge of the books and anything technology related, be it the auction’s website or their Facebook page. The two remained business partners following their separation and led the firm without fail through the years. Wacht describes her as a sister.

It was Goralski who continued the tradition of baking the famous pies that they served each auction. The tradition began with Wacht’s mother, who he described as a farm cook. “A little bit of this, a little bit of that,” he said, no recipe in hand. When she was no longer able to continue it, Goralski took over but let Wacht’s mother take the credit for the pies. When Wacht’s mother passed away, Goralski started using her own recipes, gaining the affection of bidders for decades to come. “That evolved,” Wacht said. “People started to expect that.” And they did, as every slice of pie, numbering in the hundreds, was spoken for before the final sale began.

Richard Wacht auctions off the first lot of the sale, a brass schoolmaster’s bell, for $85. His business partner Susan Goralski stood next to the podium and called out bids the entire night.

Doing business in the same area for so long meant that Wacht knew his way around. “Most of the estates we handled used to come off the shoreline,” he said. “That’s where the denseness of housing was. Up where I am, I can drive down through Farmington, Canton, Avon, Simsbury, and I’ve perhaps been in every other house on the street. I’d go into a home and the family would say, ‘We’ve lived here forever.’ I’d ask how long that was and they’d say 35 years. I’d say ‘I know, I took the antiques out of this home 35 years ago!’ They think they’re old timers and they’re really not.”

The July 27 auction was a magnet for those who had known or done business with the house through the years. Fellow auctioneers came out to see Wacht hammer down his last lot while dealers and collectors who had frequented the sale over the decades lamented that one of their great resources was trickling out its last drop.

If anyone expected Wacht to give a teary-eyed speech before the sale got underway, they probably did not know him very well. As the sale was to start and the crowd whistled and applauded, Wacht quipped, “We’re going to start the auction, and there’s a lot of stuff to sell, so please bid quickly as I’m an old man…and if you don’t bid quickly, I won’t have a lot of time left to retire.” And with that, he brought up the first lot to cross the block, a brass schoolmaster’s bell that brought $85.

The sale wove its way through the spread of early offerings: early glass, brassware, American antique furniture, paintings and prints, American and Continental pottery, carpets, clocks and more. Wacht’s auctioneering style was a joy to watch, with five of his employees at times looking out over the audience and calling out bids. There was hardly a second of the auction where his voice or those of his callers was not heard. As bidding clamored back and forth, Wacht could be seen mentally moving on to the next lot while letting his callers keep track of the bidding, he himself reaffirming those bids, but his hands and eyes had already reached for the next item and brought it up to the table. Hammer down, next lot ready.

Notable pieces of furniture included a highboy that Wacht called “one of the sweetest examples you’ll ever see,” attributing it to Rhode Island with a shell-carved center bottom drawer and a pinwheel carved center top drawer. The piece went out at $1,700. A diminutive chip-carved chest, either American Pilgrim or English, went out at $850. A Federal gentleman’s chest in a nice, small size with five drawers, pineapple carved columns and claw and ball feet sold at $575.

Before he sold off the cupboard, Wacht was surprised to find it filled with a set of Limoges china, close to 100 pieces. The set brought $90.

Country furniture found its share of interest as well. A long six-board pine blanket chest, possibly a grain bin, went out at $200, while a mid-1800s dry sink with a back cupboard sold at $240. A pine jelly cupboard would bring $480.

The staff at the auction wore a uniform red “Canton Barn – End of An Era” T-shirt that they had made up for the occasion. Wacht had one left and offered it early on in the evening, where it sold for $320. At that price, some of the staff started to consider selling their own.

A rather rare white scrimshawed lobster hook powder horn with incised date of 1730 under a colonial-era ship would bring $825.

Fine art was led by a set of three paintings on glass that brought $2,300. The paintings depicted the months of January, June and November, with scenes, respectively, showing people playing winter sports, playing in the sun and gathering wood for winter. A signed William Merritt Post painting featuring a bog with trees along the banks of a river would sell for $740. A signed G. Hunt river valley scene painting dating to 1861 featuring an American farmhouse next to a river with cows in the field brought $450. An old European Seventeenth Century painting featuring men around a tavern table would sell for $625.

Ceramics were led by a Liverpool pitcher, circa 1820, with an eagle across the front, that sold for $700. A Martha and George Washington ironstone bowl and matching pitcher would sell for $240. A Chinese antique celadon bowl with a carved stand brought $380.

There were plenty of bargains to be had and many of the lots finished under $200. A pair of early child’s chairs, $45; a Tree of Life glass compote, likely Sandwich, $50; a Nineteenth Century nanny’s rocking bench, $130; a New Haven banjo clock, $155; an early Nineteenth Century maple dough box, $100.

For many years, Canton Barn’s slogan, always included in their advertisements within Antiques and The Arts Weekly, was “Auctions are a way of life with us.” On the firm’s website, that slogan has been amended to “Auctions were a way of life with us.”

When asked what he intends on doing in retirement, Wacht proudly said, “I’m just going to do nothing for a while, because I want to do nothing. But after that, I don’t know.” He remarked that he was looking forward to seeing what life was like outside of the auction business.

In parting, Wacht said that he “appreciates all the business that people brought us through the years. There were a lot of very nice people that came through my place.

“Our heads keep telling us we can keep doing it, our bodies tell us we can’t,” he said. “But it’s all interesting, guys like us had a good run at it.”

For additional information, www.cantonbarn.com or 860-693-0601.