“Georgia O’Keeffe, Abiquiu, N.M.” by Bruce Weber (b 1946), 1984. Gelatin silver print. Bruce Weber and Nan Bush Collection, New York. ©Bruce Weber

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

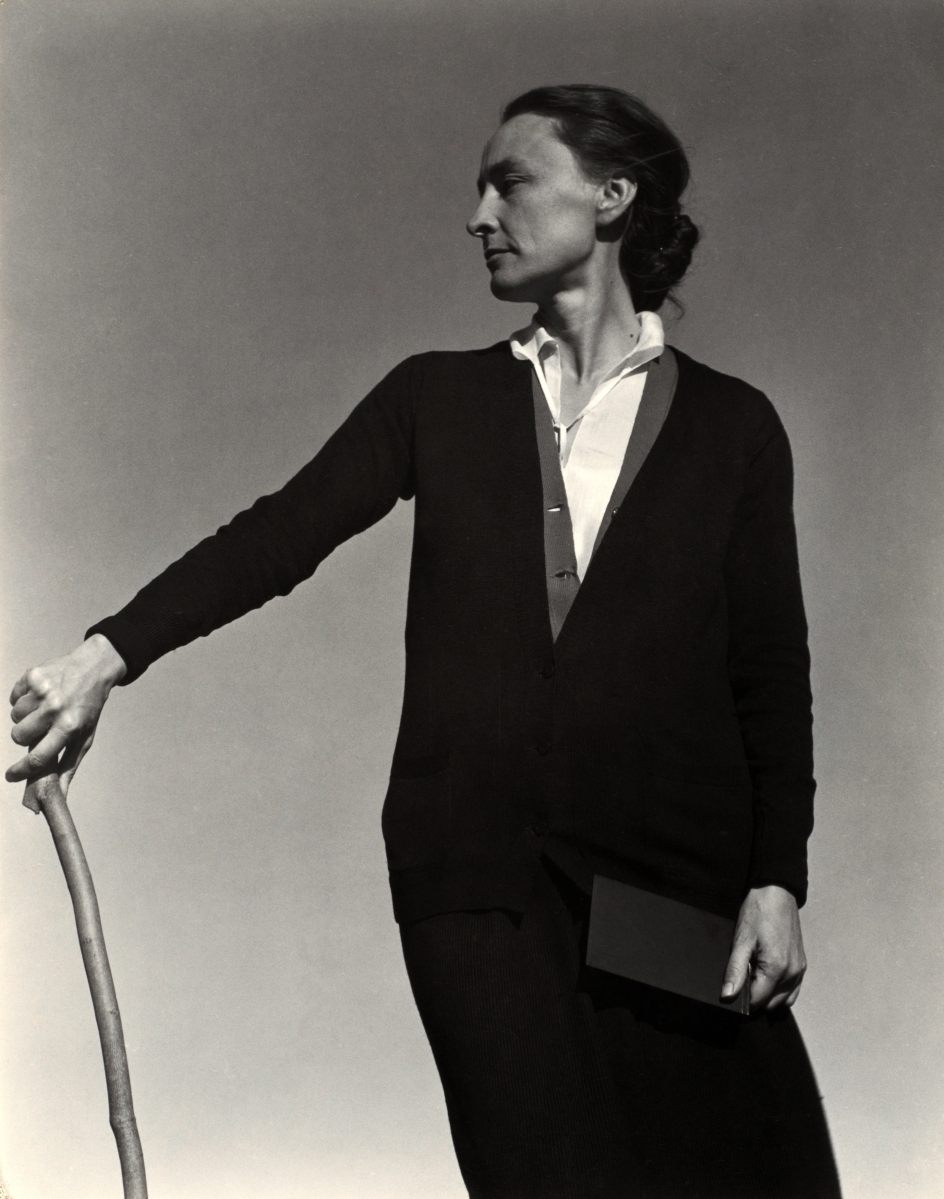

SALEM, MASS. – Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) feels familiar to us. We appreciate her, celebrate her and sense that we somehow know her not only because of her own remarkable body of work, but also because she was so often the inspiration for photographers over a nearly 70-year period.

From the beginning of her career to its end, she was known as much for her art as for her face, her form and her personal style. Many writers and curators have explored the extent to which she herself was an agent in this myth-making, but until now none have seriously examined how she did so through the clothes she created, selected, wore and lovingly saved as part of her personal archive. Curated by art historian Wanda Corn in cooperation with the Brooklyn Museum – and presented there March-July 2017 – “Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style” is on view at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) through April 1.

One of the most illuminating photographs in the exhibition long preceded the familiar, iconic portraits by Alfred Stieglitz, Laura Gilpin, Todd Webb, Bruce Weber (all included in the show) or other giants of American photography. It is of O’Keeffe as a teenage student at Chatham Episcopal School in Virginia, where her family had moved from Wisconsin a year or so before. Where her classmates appear in ballooning, beruffled shirtwaists, their hair in puffy pompadours topped by enormous cat-ear bows, O’Keeffe is in narrow sleeves, her hair pulled tight into a simple braid down her back, the ribbon performing a purely functional purpose.

Corn uses this photo to illustrate the fact that O’Keeffe’s austere personal style had an “amazing continuity,” a phrase borrowed from O’Keeffe’s contemporary Stuart Davis, from her earliest years.

“Amazing Continuity” was, in fact, the title for a talk that Corn gave to cap off a 2013 fellowship at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, N.M. It is also the title for an opening chapter of Corn’s excellent book, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, accompanying the exhibition.

The fellowship evolved when Corn, who has written extensively about how artists’ personal and domestic aesthetics engage with their art, was approached by a curator at the O’Keeffe Museum, who told her about the remarkable archive of clothing that the artist had left behind after her death in 1986. That conversation was the beginning of the astounding conglomeration of clothing, photographs, paintings and ephemera that is this exhibition.

As Corn writes in her book, “Georgia O’Keeffe drew no line between the art she made and the life she lived.” She was a true polymath: a painter and sculptor of genius, to be sure, but also uniquely gifted in other arenas that tend to be less valued – an artist’s model/muse of unparalleled influence, an incredibly skilled seamstress, a rigorous and thoughtful archivist. It is in that latter activity – in shaping, curating and documenting her own life and legacy – that she strikes a chord with so many of today’s museumgoers. At Brooklyn, Corn notes, audience feedback through social media focused on how O’Keeffe “had a brand, she had a trademark.”

While Corn confesses that she is less comfortable using such language of public relations to characterize the artist’s approach, she appreciates how it resonates with younger people, and how it helps them understand “what happens when you apply with great discipline a particular aesthetic, and that becomes your signature. I never realized,” she adds, “the degree to which a 25-year-old would think ‘that’s what I’m working on, too.'”

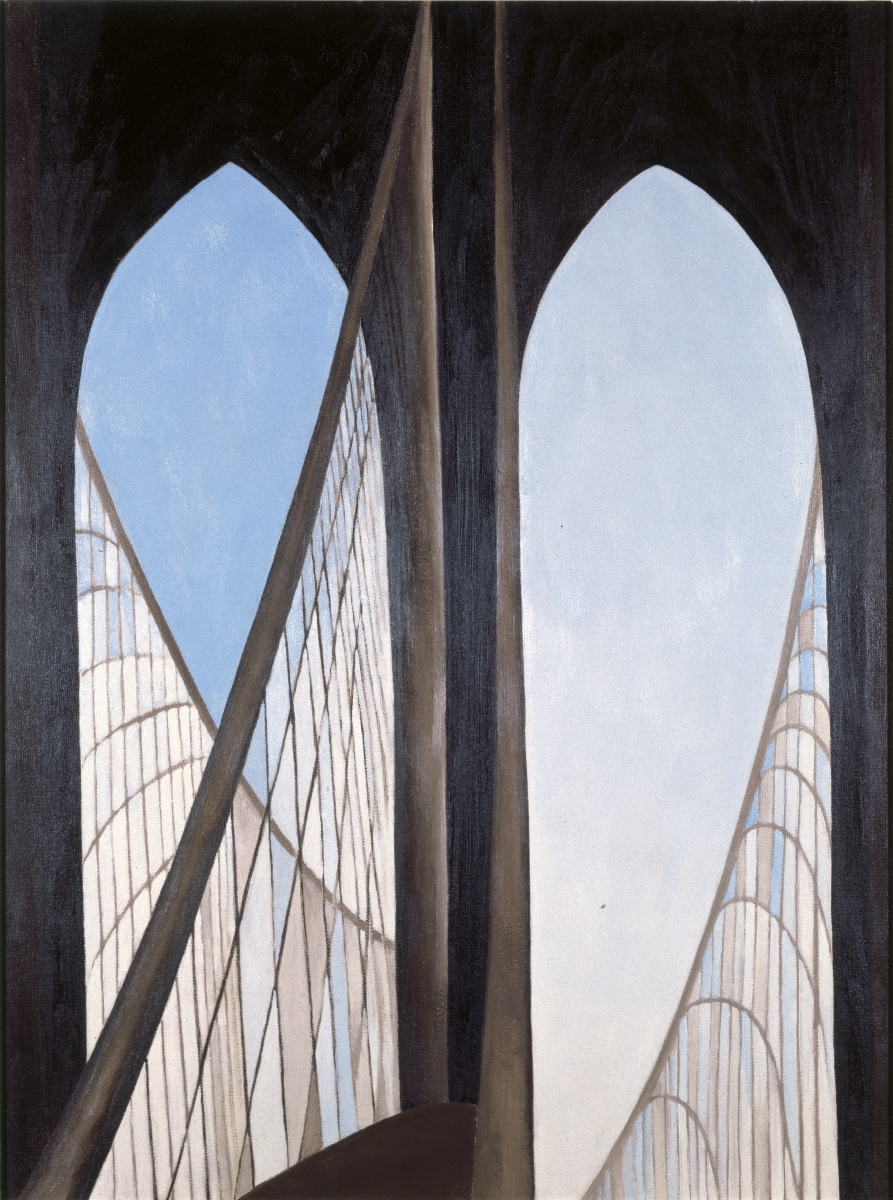

O’Keeffe’s self-invention was, at first, not purely a solo project. Her mentor, teacher, lover and eventual husband Alfred Stieglitz was initially an advisor to and a coauthor of the public face she showed to the world. He photographed her in various modes: as an object of desire but also as a powerful modern woman, a fellow artist, a denizen of nature and a kind of spiritual icon.

While the poses, expressions and camera effects vary, the clothes retain the essential features of O’Keeffe’s “amazing consistency”: the colors black and white, flowing lines, a V-shaped neckline and an overall rounded silhouette, including small hats worn close and low on the head over hair pulled smoothly back into a knot. A shot of O’Keeffe wrapped in Stieglitz’s cape – his own signature accessory – serves as well as any to illustrate the public persona that they both had a hand in creating.

“Georgia O’Keeffe” by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), circa 1920–22. Gelatin silver print. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

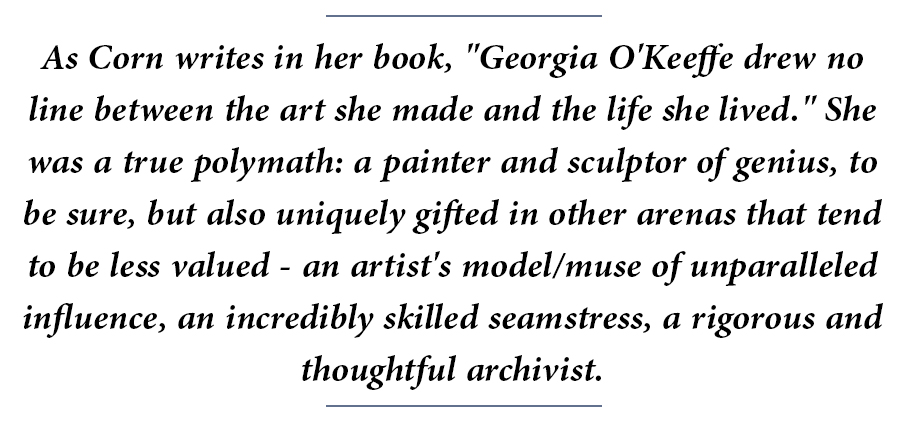

What is O’Keeffe’s alone, of course, is the artwork that she was producing at the time. Her early, pure abstractions, it seems hard to deny, explore many of the same visual motifs that her wardrobe did. A work like “Blue #2” may expand the color palette somewhat, but at the same time its rounded forms resting on slashing diagonals resonate with her own style and gestures in her portraits by Stieglitz. New York was the backdrop for their partnership, and so the city itself was a source of inspiration for them both.

What the O’Keeffe Museum collection reveals, Corn argues, is that O’Keeffe was not just making careful choices about what she wore at this pivotal point in her career; she was literally making many of the clothes themselves. A series of delicate silk and linen dresses and blouses show evidence of painstaking handwork and no manufacturers’ labels. Corn speculates that “there is only one answer” to why O’Keeffe kept them so carefully all these years: “because she had made them and they were so labor-intensive she couldn’t bear to part with them.”

Austen Barron Bailly, PEM’s curator of American art, sees a connection between the crisp pleats and delicate pintucks of these garments and O’Keeffe’s paintings. “The precision with which she executes the lines and lays down the paint on the canvas really struck me as the same kind of precision she was bringing to her work as a seamstress.” Both the artwork and the clothes are, Bailly says, “exquisitely beautiful for their restraint, use of black and white, curves and creasing.”

One delicately stitched blouse includes an impossibly perfect rosette at the neck, its form reminiscent of O’Keeffe’s renowned flower paintings like “Black Pansy and Forget-Me-Nots” or – perhaps even more directly – the fabric flowers she collected in New Mexico and incorporated into paintings like “Manhattan” and “Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock.”

As O’Keeffe became more established and successful, she invested in higher-end pieces that she wore to New York openings and favored for her formal portraits. These include suits by Balenciaga and Knize, which also dressed Marlene Dietrich, and eventually dresses by Emilio Pucci and Claire McCardell. Though we think of her as a rule-breaker in most respects, Corn argues that O’Keeffe had a firmly ingrained sense of propriety when it came to dress, perhaps a result of her middle-class Midwestern upbringing. She drew a sharp distinction between her city clothes and country clothes. Homemade smocks were for Lake George, where she spent the summer with Stieglitz’s family. Bespoke suits were for the city.

“Georgia O’Keeffe” by Alfred Stieglitz, 1929. Gelatin silver print. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

The sartorial distinction between town and country became even sharper as she began to spend more time in New Mexico and finally moved there full-time after Stieglitz’s death in 1946. The move opened up her artwork – she fell in love with the landscapes of the Southwest and with the bones and rocks she found outside the doors of her two beloved homes there – and it also opened up her personal style.

Slowly, she introduced trousers, denim and Western shirts to her wardrobe, along with some surprising bursts of color, including a suite of Marimekko dresses. And yet, Corn points out, she still regarded these as casual wear and was rarely photographed in them, preferring her standby black and white ensembles that spoke more of Manhattan than New Mexico. The exceptions were the broad-brimmed black gaucho hat that became a signature photo accessory for her, along with the long, patterned scarves – often worn underneath the gaucho – that she tied at the nape of her neck to keep the desert dust off her hair.

In time, a certain wrap dress inspired by a design by Claire McCardell, whose dresses and patterned aprons were coveted by 1950s housewives, became her new uniform. She bought the original dress in multiple colors and would wear them layered over each other, often secured by a distinctive silver belt and adorned with a monogram pin designed by Alexander Calder. O’Keeffe would come to own at least 20 iterations of this dress, and formal photographs of her from the last third of her life are more likely than not to show her wearing some version of it.

O’Keeffe’s fondness for this dress and others pushes back against the oft-repeated analysis that her style was “androgynous” or “gender-bending,” an argument made most recently in reviews of this exhibition’s Brooklyn venue. “It’s not useful to say ‘androgynous’ for nine out of ten photographs of her,” Corn says, pointing out that the way O’Keeffe dressed even in her youth was not “that far off” from mainstream “dress reform” movements for women, which emphasized freedom of movement, practical dark colors and wearing one outfit for the entire day, as men did. Sartorially speaking, O’Keeffe was less an outright rebel than an enthusiastic participant in this fashion trend that was exclusively for young, modern women. And as she matured, Corn says, she kept up this practice of “noticing what’s going on out there [in fashion] and … doing her version of it,” This is a fundamental part of her “amazing consistency.”

“Georgia O’Keeffe with Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow and the Desert” by Tony Vaccaro, 1960. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, courtesy Tony Vaccaro Studio.

The kimonolike wrap dress touches upon another major sartorial influence throughout O’Keeffe’s career. She became interested in Japanese art and design as an art student, and she wore kimonos for leisure wear throughout her life. She wears a near-transparent one draped over her shoulders in several of those early, erotic photographs by Stieglitz but did not allow anyone else the privilege of photographing her in a kimono until her final years, when she was no longer making art and was living a hermetic kind of existence. In photographs by Bruce Weber, her dark kimono gives her the appearance of a Buddhist monk, standing in contemplation in front of one of her own infinitylike sculptures, or seated with her eyes closed, as if in prayer.

Asian art is, of course, an important aspect of PEM’s permanent collections as well, and elsewhere in the museum is a display of kimonos selected specifically to resonate with the O’Keeffe show. PEM has also added to the main exhibition a section of ephemera that pays homage to the local connection of Dow’s Ipswich art school and has worked with the Vogue archives to trace O’Keeffe’s influence on fashion through the Twentieth Century and beyond. The museum has also commissioned a seamstress to create some of O’Keeffe’s more remarkable fabric techniques in touchable swatches for visitors.

“[It] tells you so much more than the canvases alone,” says Bailly. Corn agrees, noting that “you can learn things that you can’t learn in any other way” through studying the material of artists’ daily lives, like their clothes and their homes. O’Keeffe was a celebrity, to be sure, and a self-fashioner par excellence, but her lasting influence is about more than just a lifestyle brand. “Everything in her life,” says Bailly, “was a creative expression of her aesthetic values and philosophy.”

Peabody Essex Museum is at East India Square, 161 Essex Street. For more information, 978-745-9500 or www.pem.org.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama , the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.

.jpg)