By Rick Russack

PORTSMOUTH, N.H. – Continuing through September 30, the Portsmouth Historical Society’s Discover Portsmouth Center is presenting a comprehensive,three-part exhibit giving credit to Gertrude Horsford Fiske (1879-1961) and other women artists. Fiske was an accomplished Impressionist painter who trained under Edmund Tarbell, Frank Benson and others. Perhaps not as well known today as some of her contemporaries, she won many awards during her lifetime. Some consider Fiske to be at least the equal of Tarbell and as good as Mary Cassatt.

“Gertrude Fiske: American Master” features 65 of her works, including several award-winning paintings not seen since her death. A heavily illustrated exhibition catalog with essays by Carol Walker Aten, exhibition curator Lainey McCartney and Richard M. Candee accompanies the show. The first study of Fiske to be published in decades, it places the artist in context with Candee’s essay on three Fiske contemporaries and concludes with an examination of women artists working in the New Hampshire Seacoast region today.

Concurrently with the Fiske exhibit, the upstairs gallery at the Discover Portsmouth Center is presenting “Seacoast Masters Today,” showcasing about 40 works by contemporary women artists Amy Brnger, Donna Harkins, Sydney Bella Sparrow and Pamela DuLong Williams. Running concurrently, “Sisters of the Brush and Palette,” featuring 35 works, recognizes Fiske contemporaries Anne W. Carleton (1878-1968), Margaret J. Patterson (1867-1950) and Susan Ricker Knox (1879-1954), who trained and painted in Boston, Portsmouth and southern Maine.

Gertrude Fiske was one of six children born into a wealthy Boston family. Educated in Boston’s best schools, she was an equestrian and a serious golfer who won the Amateur Golf Championship of Massachusetts in 1901. In 1904, at the age of 25, she enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and discontinued her earlier pursuits to concentrate solely on her painting. She was one of the few students to complete the full seven-year curriculum. By the time she enrolled, 85 percent of the student body consisted of women, many of whom found professional success. Being an artist was one of the few respectable ways for upper-middle-class women to earn a living. After Fiske completed her coursework in 1912-13, she spent time in France, sketching as she traveled.

Fiske also studied with and worked beside Maine painter Charles H. Woodbury (1864-1940), who established the Ogunquit Summer School of Painting and Drawing in Maine. Fiske followed his recommendation to “paint in verbs, not in nouns.” During the first few decades of the Twentieth Century, an art colony established itself in the Ogunquit area, attracting notable Modernists, among them George Bellows and Edward Hopper.

Fiske also studied with and worked beside Maine painter Charles H. Woodbury (1864-1940), who established the Ogunquit Summer School of Painting and Drawing in Maine. Fiske followed his recommendation to “paint in verbs, not in nouns.” During the first few decades of the Twentieth Century, an art colony established itself in the Ogunquit area, attracting notable Modernists, among them George Bellows and Edward Hopper.

Fiske and fellow artists formed the Ogunquit Art Association in 1928. She was also the first woman appointed to serve on the board of the Massachusetts State Art Commission. The appointing board said, “Fiske ranks with the foremost painters in the country…and there are few artists who have been awarded more prizes than Miss Fiske in the entire country. There is a note of personal distinction in all of her work – a virile note.” Fiske was also elected a full member of the National Academy in 1930.

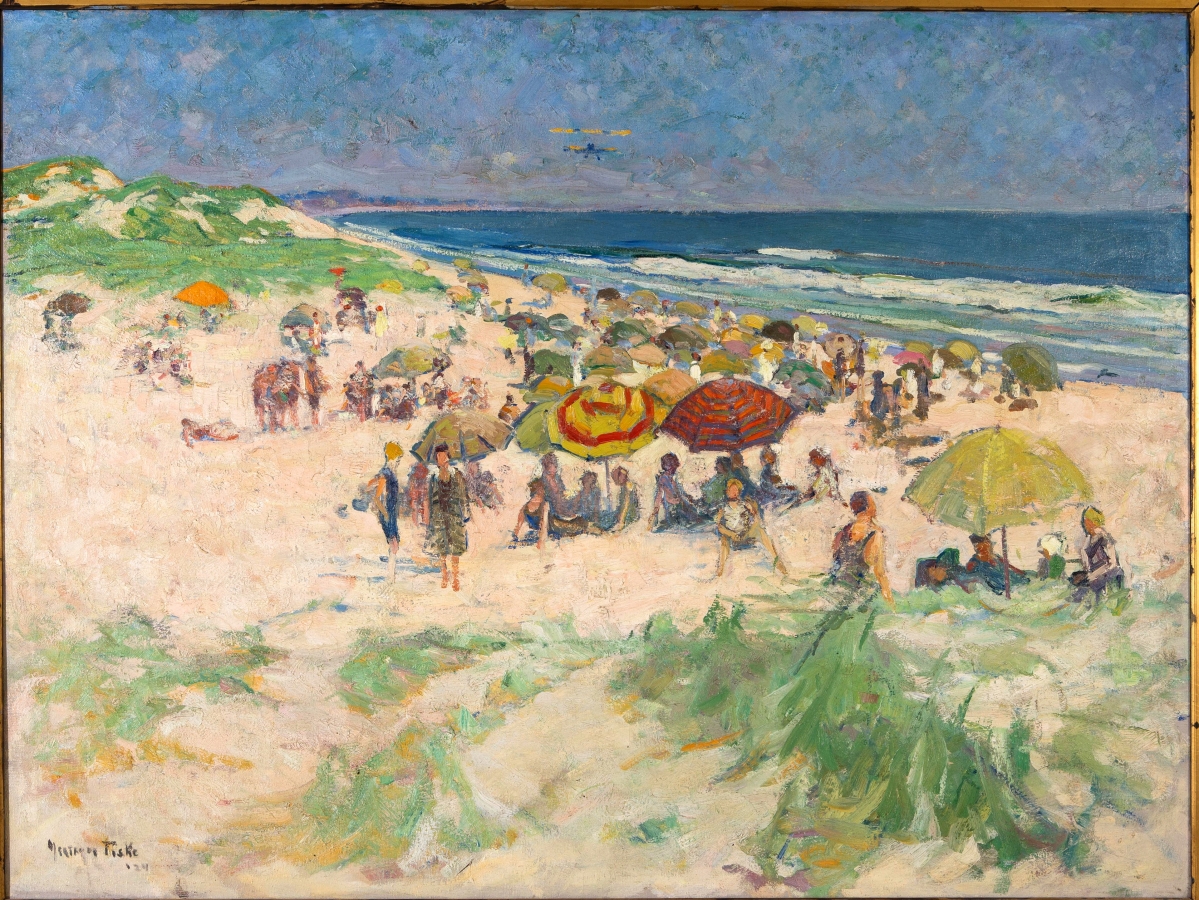

Fiske was known for her strong depictions of women in traditional scenes, showing women in interiors with power, instead of gentility and fragility. She included both men and women in her compositions, used bold colors and was respected for her likenesses of male artists. She often portrayed distinctive New England characters, including florists, craftsmen, postmen and fishermen. She also painted landscapes in the area around Ogunquit and Revere Beach in Massachusetts, a stone quarry near her home in Weston, Mass., and at the Navy Yard in Portsmouth, N.H.

Walker Aten writes in the catalog, “The shadow and light-infused interiors of Fiske’s winter training at the Museum School were complemented by the bright, ocean-side summer classes in Ogunquit, and ultimately Fiske evolved a unique style that freed her from the Boston tradition both in manner and subject. The painterly style that would be the hallmark of her mature works can be first seen in her landscapes and beach scenes. She included the artifacts of the modern landscape in her paintings – utility poles and wires, automobiles, airplanes… She later took the spontaneity and breadth of color found in Woodbury’s marine and landscape paintings and applied those to her work, creating a new, fresh and Impressionistic manner that was much unlike her earlier works.” The exhibition reflects her professional evolution.

Fiske, who never married, had the financial means to paint full-time. Her paintings were exhibited both locally and in museums such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Corcoran Gallery, Art Institute of Chicago and Detroit Institute of Arts. In 1915, she won a silver medal for her painting “The Shadow” at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. By 1935, Fiske had exhibited in 11 one-woman shows and won some 18 prestigious awards, including the National Academy of Design’s Shaw and Clarke Prizes. Throughout her career, she painted mostly portraits, many commissioned and many more of characters or models who intrigued her. Fiske was also an etcher, producing bold, lively prints, often renderings of her own paintings, and became a member of the Boston Society of Etchers and the Chicago Society of Etchers. Five of Fiske’s etchings are included in this show, along with her press and printing materials. Her last show was more than 30 years ago, in 1987, at Boston’s Vose Galleries.

Much of the documentary material and many of the paintings in “Gertrude Fiske: American Master” were preserved by the caretakers of her estate, who allowed the inclusion of several pieces that have not been seen publicly in years. Other lenders include the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, the Farnsworth Art Museum and private collectors. The exhibition features prize-winning pieces that have been out of the public eye since her death. In her lifetime, Fiske was represented by the Vose Galleries, which sold its first Fiske work, a self-portrait, in 1917. Vose continues to represent the Fiske estate.

By including works by Fiske’s female contemporaries, Discover Portsmouth documents the role of women artists during the emancipation era. As McCartney writes in her essay, “The social/political energy around women’s rights at the turn of the century encouraged a new autonomy, which is seen translated to bolder ideas and execution on canvas.”

In “Sisters of the Brush and Palette,” paintings by Anne Carleton, Margaret J. Patterson and the notable Portsmouth artist Susan Ricker Knox provide additional context. Their work documents the wide range of artistic success women enjoyed at a time when art training was a step toward economic and emotional independence. Knox’s work was well received in her lifetime. She is perhaps best known for a series of 32 paintings of scenes at Ellis Island, done in 1920-21. When they were exhibited in New York, they were considered to “depict forcibly the real tragedy which some of the aliens meet on arrival here,” according to the American Magazine of Art.

A lecture series accompanies the exhibitions. The 90-page catalog is available from the Discover Portsmouth Center, 10 Middle Street. For further information, 603-436-8433 or www.portsmouthhistory.org.

Contributing editor Rick Russack is a retired books dealer. He created and maintains three websites devoted to the history of New Hampshire, where he resides.