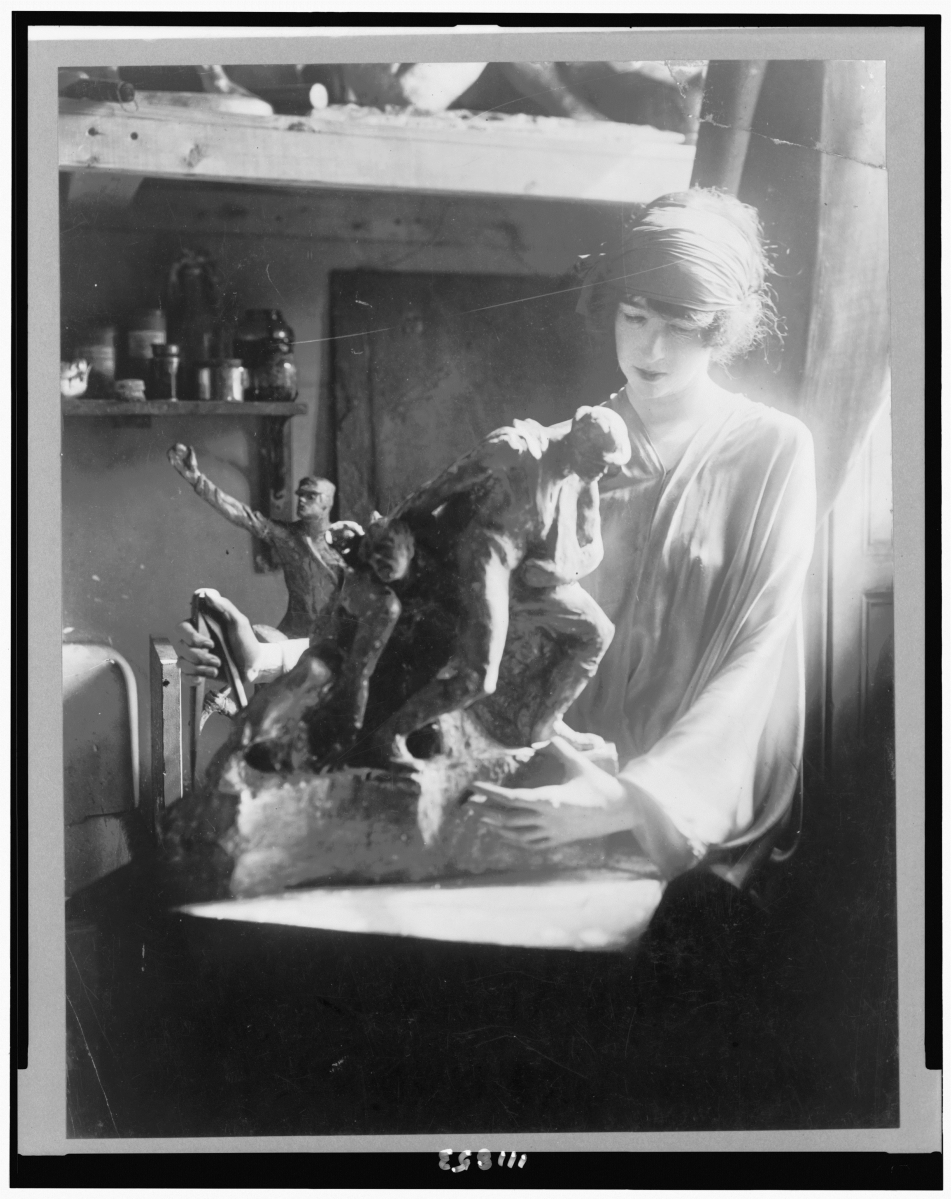

“Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Working at Her MacDougal Alley Studio” by Jean de Strelecki (Polish, 1882–1947), circa 1919. Courtesy Library of Congress.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

WEST PALM BEACH, FLA. – A number of important exhibitions in recent years have renewed efforts to explore the role of women in Twentieth Century art. Curators from Florida to Los Angeles have surveyed women Modernists in interwar New York, in the Abstract Expressionist movement and women who have worked in abstract sculpture. Such valuable scholarship remains ongoing. Less common, however, even in the age of #metoo, are sustained examinations of individual women artists, the kinds of retrospectives that have made male artists’ reputations during their lifetimes and preserved their legacies after their death.

While certainly not unprecedented, retrospectives of woman artists are rare enough that in 2015 it was newsworthy when the Museum of Modern Art mounted two back-to-back in one summer: Björk and Yoko Ono. The unprecedented happening gave rise to numerous think pieces, some positive and some taking a dim view of MoMA endorsing women who, they felt, were notable for reasons that had little to do with achievement in the visual arts.

But solo exhibitions are indispensable for establishing an artist’s legitimacy in the first place, and for assessing her or his role in the canon of art history and criticism. Individual artists rarely fit neatly into the shoebox of their own moment in time and the company they keep. They must be regarded on their own terms, not only in the pages of books but also in galleries and museums. This essential milestone, which has long been less accessible to women artists than to men, is what curator Ellen Roberts is now attempting to do with “Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: Sculpture,” on view at the Norton Museum of Art through April 29.

This is not an entirely new effort for Roberts, who was the curatorial voice behind “O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York,” covered by this publication in 2016. That exhibition gave unprecedented, individualized visibility to three of the four included artists (O’Keeffe being the obvious exception) who have been historically underrecognized and, in the case of Torr and Zorach, had gone without a major museum retrospective. The special concerns of women artists, Roberts says, has been of interest to her since she was on staff at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where she worked on Erica Hirshler’s groundbreaking exhibition “A Studio of Her Own” (2001). “Many of them were dealing with the same issues that women … deal with today,” she says. “It’s still a very compelling topic, and I think it’s very relevant still for today.”

But assessing the artistic career of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney offers unique challenges. Most other women artists of her time – and male artists, too, it should be acknowledged – worked within the boundaries of a Modernist art movement that was dominated by painting and aesthetically circumscribed by men. Men were the teachers, the gallerists, the promoters and the driving force behind the inexorable move toward abstraction that defined much of Twentieth Century art. Whitney, by contrast, a scion of two of the wealthiest families in America, had the financial freedom and wherewithal to do more or less what she liked: choosing her own private teachers, building her own customized studios (there was more than one) and pursuing the subject matter and aesthetic ideals that intuitively appealed to her.

“One of the reasons that she remains less well known today is that she did work in a variety of styles,” Roberts says, adding that because her work “remained grounded in the visible world,” it “does not play much of a role” in the schoolbook art-historical narrative of the Twentieth Century, where the rise of pure abstraction in the postwar period is presented as a culmination of artistic achievement. Robert’s mission, in part, is to dismantle that narrative in the context of Whitney’s work. “Twentieth Century art is actually much more complicated than those first historians thought,” she remarks. “People were working in abstract modes and realist modes at the same time.”

“One of the reasons that she remains less well known today is that she did work in a variety of styles,” Roberts says, adding that because her work “remained grounded in the visible world,” it “does not play much of a role” in the schoolbook art-historical narrative of the Twentieth Century, where the rise of pure abstraction in the postwar period is presented as a culmination of artistic achievement. Robert’s mission, in part, is to dismantle that narrative in the context of Whitney’s work. “Twentieth Century art is actually much more complicated than those first historians thought,” she remarks. “People were working in abstract modes and realist modes at the same time.”

Whitney’s wealth, coupled with her gender, also brushes up against her identity as a professional sculptor, then and now. “Her wealth gave her a lot more leeway than many of her contemporaries had, but it was still challenging,” says Roberts. “It was typical for a wealthy woman to kind of dabble in the arts, and it was very difficult for her to get people to take her seriously.” She was able to invest significantly in her art – the lessons, the studios, the travel, the studio assistants, the nannies – and yet her very ability to commit herself in this way separated her to a great extent from the community of Modernist artists who had all struggled through art school together and then shared studios, materials, babysitters and cold-water flats as they competed for gallery representation and spots in juried shows. Whitney’s distance from that scene – both socioeconomically and aesthetically – is part of why she is not primarily recognized as an artist today.

Another reason, and probably the most important one, is that Whitney would eventually gain art-world fame for an entirely different set of achievements: her patronage as a gallerist and a collector of her contemporaries’ works, the striking figure she cut as a muse to photographers and painters like Robert Henri and her founding of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, the first museum to be dedicated exclusively to American art. During her lifetime, she was recognized as a leader of the New York art world, one of few women of her time who might reasonably make that claim. Even so, at the time of her death, The New York Times identified her first and foremost as a sculptor, headlining her obituary “Mrs. H.P. Whitney, Sculptor, Is Dead.” “That changed quite rapidly,” says Roberts, “in part because of the direction of the history of art in the Twentieth Century,” and, it must be acknowledged, because her philanthropic work was indeed so visionary and exceptional.

But it would be a mistake to discount Whitney as an artist because we are more comfortable thinking of her in other, more familiar, terms. This would be to do to her what was done to Yoko Ono from the moment she became more famous for her romantic life than her art. Whitney was “very ambitious,” Roberts says, “and she very much wanted to be taken seriously as a professional sculptor.” This exhibition and its accompanying catalog set Whitney’s philanthropy entirely aside to focus on her artwork, which Roberts persuasively argues was visionary and exceptional in its own way.

Model for Washington Heights and Inwood Memorial, New York, modeled 1921–22, cast 1922. Private collection. —Jacek Gancarz photo

After several years of focused study – a chronology in the catalog by Norton’s curator of education, Erica Ando, describes those early years – Whitney sought to make a name for herself through prestigious commissions. Family connections played a role in some early coups, but soon she was winning open competitions for major projects, some publicly funded. Many of her public works, like her monument to the American Expeditionary Forces in Saint-Nazaire, France, and her fountain originally designed for the Arlington Hotel in Washington, DC, exist now only in altered form: the Saint-Nazaire monument, destroyed by German forces in 1941, was rebuilt in 1989; the Arlington fountain was never built as conceived, though versions exist in Canada and Peru. But others remain more or less in situ, including her affecting commemoration of the men who gave their lives to save others during the sinking of the Titanic (Washington, DC) and her energetic, bronco-busting “Buffalo Bill” (Cody, Wyo.).

This creates logistical problems for the modern curator, of course. “I think without dealing with the public sculpture, you haven’t really dealt with her career,” says Roberts, “but trying to represent that in an exhibition setting is really difficult.” Luckily, Whitney’s methodology ensured that there are studies and sketches – both drawn and modeled – for nearly every major work she completed. A plaster model of the Arlington fountain demonstrates the artist’s inventive solution to the challenge of the fountain form and her facility with the heroic male nude, while graphite sketches and bronze models of the Titanic and Saint-Nazaire monuments give a sense of their sweeping lines and moving spiritual symbolism. In both pieces, the central figures arms are outstretched, crucifix-like, in a gesture of sacrifice. For the latter two pieces as well as “Buffalo Bill” – arguably her best-known public works – there are also a multitude of historical photographs, giving a sense of the works’ monumental scale and popular appeal, as crowds press in to get a look.

The Saint-Nazaire monument reflects a sustained interest that Whitney had in the toll of war on the individual. Having served as a Red Cross nurse in France during the First World War, Whitney witnessed the horrors of the conflict firsthand, giving her a perspective that few other American artists had. Most sculpture related to World War I was patently heroic, and while Whitney’s Saint-Nazaire monument undeniably fits that mold, her other works, Roberts says, were “not glorifying [war] but instead thinking about it more as the tragedy that it really was … [which was] unusual at the time.” This is most evident in a rarely seen group of small studies of individual soldiers that Whitney modeled not for any specific commission, but to work out her own feelings about the war she was living through. The realistic, unidealized features of the works and the narrative titles she assigned them -“Orders,” “Home Again,” etc – suggest real lives behind the materials, both expanding and personalizing the same concepts she explored in her major commissions.

On the advice of a friend, Whitney had her clay studies cast in bronze to preserve them, and she exhibited them at her own Whitney Studio in 1919. The studies would later provide inspiration and a visual language for a monument, still in place, for New York’s Washington Heights neighborhood (a bronze model is in the show) and the large bronze relief panels she produced for architect Thomas Hasting’s “Victory Arch” in New York’s Madison Square. While the original arch is no longer standing, slightly smaller versions of Whitney’s reliefs remain in the collection of Whitney’s Long Island studio, now a house museum, and are included in this exhibition.

War panel for the Madison Square “Victory Arch No. 2,” 1919. Bronze, 25 by 65 by 6 inches. The Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Studio, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Later in life, Whitney remembered the individual war studies as the “first time” that she had “been able to approach what is in me to say.” Though she had always courted public success and the legitimacy that it gave her, it seems that she found a special kind of satisfaction in work that she made more purely on her own terms. Some of these pieces, including her alluring self-portrait, “Chinoise,” convey the same kind of serene idealism of many of her public sculptures. But others were more like the war studies: rougher, expressionistic works that gave an aura of realism.

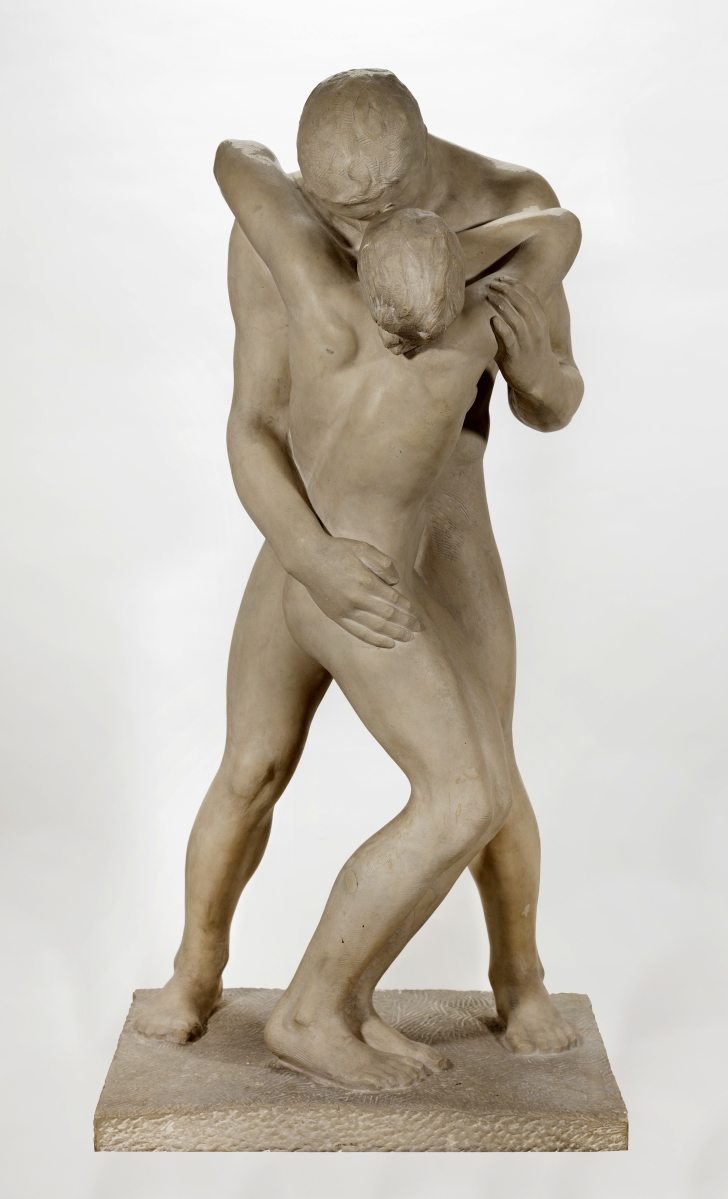

She made such pieces from the earliest days of her professional career. Early examples include a portrait of her friend and fellow artist Jo Davidson and a bust, “Spanish Peasant,” that she exhibited in the 1911 Paris Salon. But later, when opportunities for public commissions dried up during the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Whitney used the time to explore in a more sustained way what was “in her to say.” “John” and “Gwendolyn,” two portrait busts of either local working people or family servants, express not only her conviction that all human lives were worthy of expression in art, but also her remarkable ability to work simultaneously in drastically different styles. And works like “Daphne” and “The Kiss” express her lifelong admiration for that other master of sensual, expressionistic bronzes, Auguste Rodin, whom she had met in Paris early in her career.

The impression she made upon the great French sculptor, as much as anything, argues the case for assessing Whitney on her own terms, as an artist and not an heiress. “I receive many foreign artists,” Rodin wrote to a friend shortly after meeting her. “There are among them women and sometimes fashionable women … they think they are making sculpture to amuse themselves and astonish their friends, but they do not have the moral courage which is necessary to truly liberate themselves from the prejudices of their milieu. One came to me, however, who is an exception… She is an American named Gertrude Whitney. She has the gift. I think that she will go very far. Remember her name and try to follow her exhibitions.”

“Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: Sculpture” will travel to the Planting Fields Foundation in Oyster Bay, N.Y., in June and to the Newport Art Museum in Rhode Island in 2019.

The Norton Museum of Art is at 1451 South Olive Avenue in West Palm Beach. For information, go to www.norton.org or call 561-832-5196.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama, the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.