Serpent labret with articulated tongue, Aztec, 1300–1521. Gold, 2-5/8 by 1¾ by 2-5/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By James D. Balestrieri

LOS ANGELES – If there was anyone in the early 1980s who did not want to be the swashbuckling archeologist Indiana Jones, I did not know him or her. Considering the dazzling objects arrayed in “Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas,” presented at the Getty Center as part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, Dr Jones and the prizes he pursued readily spring to mind.

On view through January 28, “Golden Kingdoms” presents more than 300 artifacts from recent archeological excavations in Peru, Columbia, Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala and Mexico. It examines the development of goldworking and other arts between roughly 1000 BCE and the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, emphasizing the historical, cultural, social and political conditions that fostered cultural exchange.

The story moves us from south to north as various luxury materials and artistic practices, metallurgy in particular, spread from the Andes to Central America, from Mesoamerica to Mexico – whose trade extended north to the turquoise mines of Chaco Canyon. These practices and the objects they produced articulate a relationship to nature that is hard for those of us raised in European traditions to envision. But in all of them, from Moche to Inca, from Mixtec to Aztec, nature was a vital force to be emulated, embodied and appeased, rather than a resource to be imitated, extracted and conquered.

With that as a springboard, we can begin to see beyond the dazzle and apprehend the challenge that the objects in “Golden Kingdoms” pose to Western notions of value and luxury, and appreciate them on their own terms. We can also begin to understand something of the clash of civilizations – indeed, of entire worldviews – that occurred when the Spanish began to conquer the Americas in the Sixteenth Century.

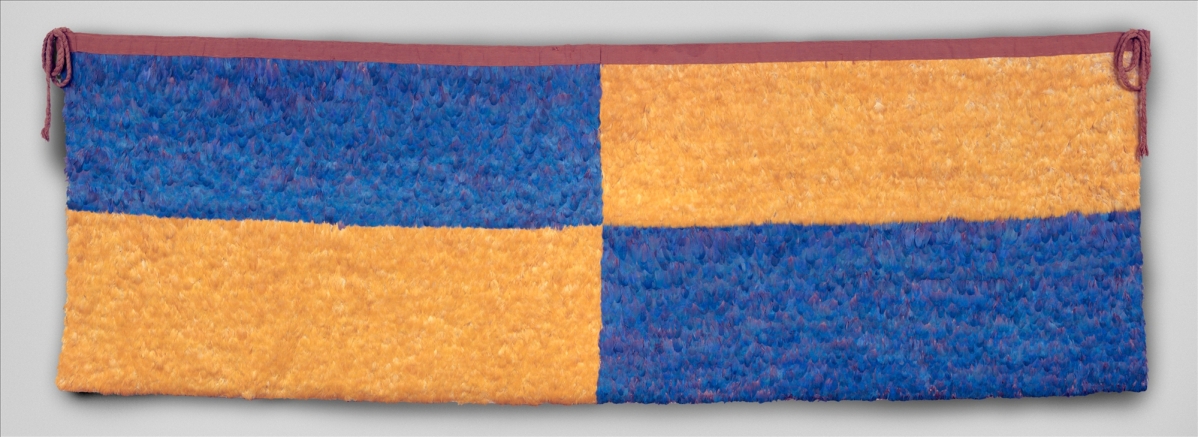

Consider gold. To the Spanish, gold was the object of the exercise, the treasure at the end of exploration. To the indigenous peoples of the Americas, gold was prized for its power, for its connection to the earth, for what it could do rather than for its worth as a medium of exchange. To these peoples, who could not comprehend the rapacity of the Conquistadors, gold ranked behind the feathers of rain forest birds like the Quetzal, behind the spondylus shells that divers plucked from the deep, behind jade and turquoise, behind even some exquisite weavings, textiles that conferred and conveyed power.

Consider gold. To the Spanish, gold was the object of the exercise, the treasure at the end of exploration. To the indigenous peoples of the Americas, gold was prized for its power, for its connection to the earth, for what it could do rather than for its worth as a medium of exchange. To these peoples, who could not comprehend the rapacity of the Conquistadors, gold ranked behind the feathers of rain forest birds like the Quetzal, behind the spondylus shells that divers plucked from the deep, behind jade and turquoise, behind even some exquisite weavings, textiles that conferred and conveyed power.

But what is this power? In his 2004 book The Incas, the standard work in English on the subject (and a very good read), Terence N. D’Altroy, a Columbia University faculty member, offers some ways in to a difficult topic. In one chapter, “Thinking Inca,” D’Altroy describes the Inca concept of camaquen, or vitality, as an inherent animacy in all things, living and dead, animate and inanimate. Imagine mummies of rulers treated as if they were still alive. D’Altroy writes, “We can also understand how vitality worked by examining the Incas’ views of rulers and their personal objects, some of which were living icons… Although the Spaniards described them as idols, Incas considered them to be the ruler – that is, to share the same camaquen – not simply to represent or substitute for him in the absence of his person/mummy.”

Perhaps a way for us to envision this is to imagine the Christian tenet of transubstantiation without the “trans,” without the symbolic infusion of life. The bread and wine do not become flesh and blood through the ritual of communion, the ritual is a performance that confirms the camaquen.

D’Altroy continues, “Andean peoples also thought that things composed of the same substance shared an inherent essence. An object made of metal or stone, for instance, contained that essence as part of its being, even if it were covered, broken up, mutilated or perhaps even incinerated.” Later, he touches on the idea of creating art, saying that the Incas “felt that some things used to make other objects had the power of camay, that is, the ability to infuse something else with animacy. Tools such as the ceramic molds that were used to make figurines possessed that capacity.”

Mouth mask with feline creature and human figures, Cupisnique/Chavín, 800–550 BCE. Gold, 5¾ by 8-3/8 by 1/8 inches. Museo Kuntur Wasi, San Pablo, Peru, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

So vitality passes from the gold in the ground to the object made from it, through the craftsman to the person who owns it, displays it, performs with it. Even broken, the pieces continue to have vitality, even as the dead remain vital. There is no interest in ownership of the object; channeling its vitality, to make it serve you – your story, your goals – as an emblem of power is the object of extracting and shaping the metal, or any of the other raw materials that moved the indigenous peoples of the Americas. As a medium of exchange, its value is as an offering to a deified aspect of nature, the same nature that gave rise to the raw material – the metal, feather, shell – from which the object was fashioned. It is a cyclical notion of value, one that is not intrinsic to the object, but dependent on the object’s performative efficacy in time-space.

Look at the natural forms – animal and geometric – that comprise the artworks in the exhibition, forms that appear to be extracted from an endless, eternal, interlocking latticework of musical repetition and variation. You must pause to wonder what these exceptional artworks, rare survivors each and every one, meant to those who made them, those for whom they were made, and those who saw them. D’Altroy speaks to this phenomenon: “We need to pay attention to what constituted an object that made cultural sense in the application of power. Partial objects, or their essences, could have power, while other objects only fully existed as part of a group of things. In contrast, some beings (the ruler) or objects could be present simultaneously in various forms in multiple locations.”

Archaeology is filled with stories of missing and looted objects. Existing objects often lack context. Where the indigenous people have no written language, as was largely the case in the Pre-Columbian Americas, the researcher is dependent on conquerors’ records, in this case, the Sixteenth Century codices of Spanish clerics who sought to record the languages and customs of the peoples they were tasked to subjugate and convert to a religion that was entirely alien to them.

How can we know a people whose spatial metaphors for past and future are diametrically opposed to ours? How can we apprehend the immanent shimmer of vitality, of camaquen, that inheres in all the things of this world, and every other? How much can we infer about art in societies that might not have understood what we mean by art, especially when we know so little about the workshops where the golden octopus and the spider nose-ornament, the feathered robe and the Quetzalcoatl spectacles, the burial masks of shell, jadeite and turquoise were designed and fashioned, when we know so little of the economics of luxury trade – sometimes over great distances. Did these objects enhance divinity, imitate and therefore appease nature, cement treaties, serve as tribute? Or are our categories woefully insufficient?

Octopus frontlet, Moche, 300–600. Gold, chrysocolla, shells; 11 by 17 by 1¾ inches. Museo de la Nación, Lima, Peru, Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

Indiana Jones knows that there is more to archaeology than treasure hunting, that the treasures he seeks have unknown and untapped camaquen, often to what might be called a “grievous bodily harm” degree (viz: Ark of the Covenant, Sankara Stones, Holy Grail, Crystal Skull). But to the scientist – who must also be an adventurer – the unknown beckons rather than dissuades. I happen to have a good hat and good boots that have seen some hours in fields of fossils and shards. I can let my mustache – though it has long gone gray – grow back. After “Golden Kingdoms,” if the future should happen to come around from behind and present itself, challenging my worldview one trowelful at a time, I am ready for it. Give me half an hour to pack.

“Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas” was co-organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Research Institute and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was curated by Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson curator of the ancient Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum; and Kim Richter, senior research specialist at the Getty Research Institute. Following its close at the Getty Center, the show travels to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it will be on view between February 27 and May 28. Edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts and Kim N. Richter, a catalog of the same name accompanies the exhibition.

The Getty Center is at the intersection of North Sepulveda Boulevard and Getty Center Drive. For information, www.getty.edu or 310-440-7300.

Playwright, author and critic Jim Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York.