“Gold miners with sluice” by unknown maker, California, circa 1852. Daguerreotype, quarter plate, 3¼ by 4¼ inches. —Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc.

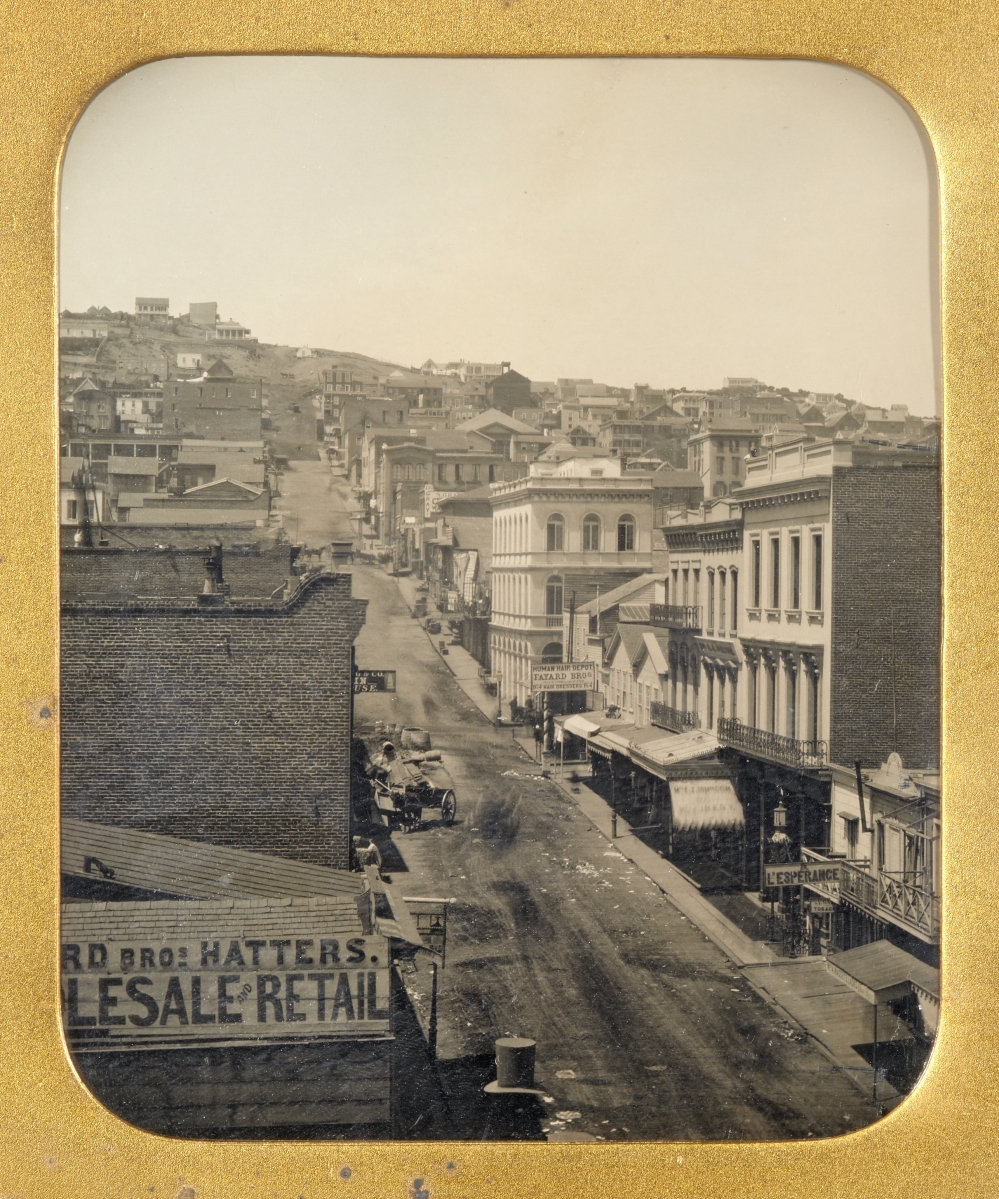

By Karla Klein Albertson

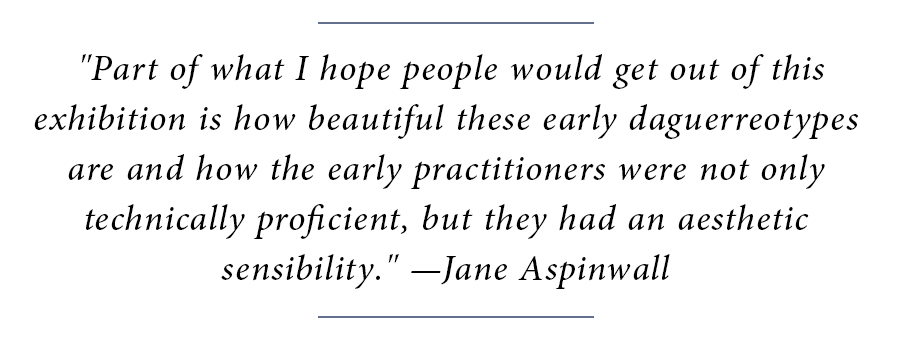

KANSAS CITY, MO. – At the midpoint of the Nineteenth Century, photography in the form of daguerreotypes and ambrotypes was able to capture the actual appearance of people and their surroundings with greater accuracy than artistic portraits and landscapes. By the time news of the discovery of gold in California was widely published in 1849, camera techniques had achieved enough mobility that photographers could travel not only to major cities but even to the small settlements and mountain areas where actual prospecting was underway.

The frenzy which drew eager amateurs westward is easy to comprehend, for gold is a gleaming thread that runs through the history of the world. Whether it emerges from Egyptian tombs or English fields, gold is the rare substance which survives the ravages of time bright and unaltered. Therein lies its value and the promise of riches for those who find it. By land and sea routes, people flocked to the gold fields not only from the East Coast and Europe but also from Canada, South America, Asia and Australia.

Early images of people and places involved in this special quest – over 90 in all – are the subject of a new traveling exhibition, “Golden Prospects: Daguerreotypes of the California Gold Rush,” organized by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which will travel to venues in New England in 2020. For some exhibitions, touring the galleries is a complete experience. To better understand these small images, however, the well-researched accompanying catalog provides a key that unlocks multiple facets of that special period. The chapters explain not only the techniques of early photography and the methods by which gold could be mined but also explore the origin and social composition of the fortune-seekers who transformed California’s cities and altered population trends on the West Coast.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is perfectly equipped to organize an exhibition of this significance. The beautifully-constructed institution, which opened in 1933, is one of the great Midwestern museum palaces created by wealthy donors in the Twentieth Century. Strong in multiple areas with more than 35,000 objects in its permanent collection, the museum is perhaps best known for one of the most important collections of Chinese art in the Western Hemisphere. In 2007, the architecturally innovative Bloch building was added to the complex, and the photography galleries are located there.

Museum director Julián Zugazagoitia wrote in his foreword to the catalog: “As part of our comprehensive survey of Nineteenth Century American photographs, NAMA has one of the nation’s largest holdings of California daguerreotypes and ambrotypes. As a result, more than half the works in the accompanying exhibition are drawn from our permanent collection. This museum began exhibiting photographs in 1936 and made its first major purchase in 1957. In late 2005, it was transformed with the acquisition of the famed 6,500-piece Hallmark Photographic Collection.”

The Hall family and the Hallmark company they founded are based in Kansas City. Exhibition organizer and curator of photography Jane Aspinwall worked with their photographic collection before its donation to the museum, but her study of Gold Rush images has even deeper roots in the research that she undertook for her doctorate: “I started making research trips around 2014 and have visited many, many collections. I think, I visited 33 different institutions and private collections in order to amass this database. Almost everything I discovered was new – something I didn’t know that existed. I was able to make attributions that hadn’t been apparent without amassing this critical amount of material.

“For George H. Johnson, who was one of the preeminent daguerreotypists of outdoor views in the gold region, there’s a nice body of work – about seven or eight views he took at Grizzly Flats, and it gives a great insight into his methods. He looked at multiple viewpoints and was really kind of working the scene. That was something that was quite surprising to me, because we think of daguerreotypists as setting up the camera, taking one picture, then packing up and moving on. So, it was interesting to see him getting the most out of that locale.”

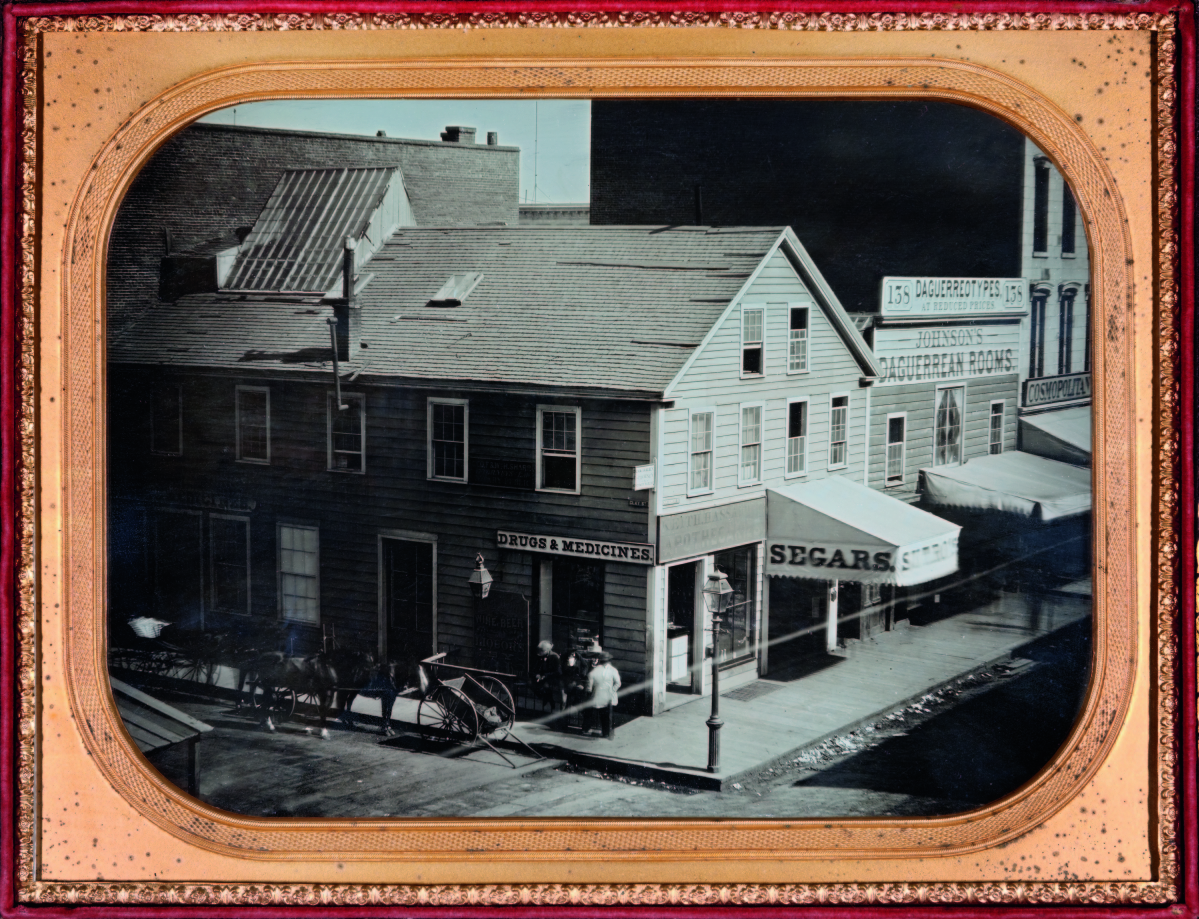

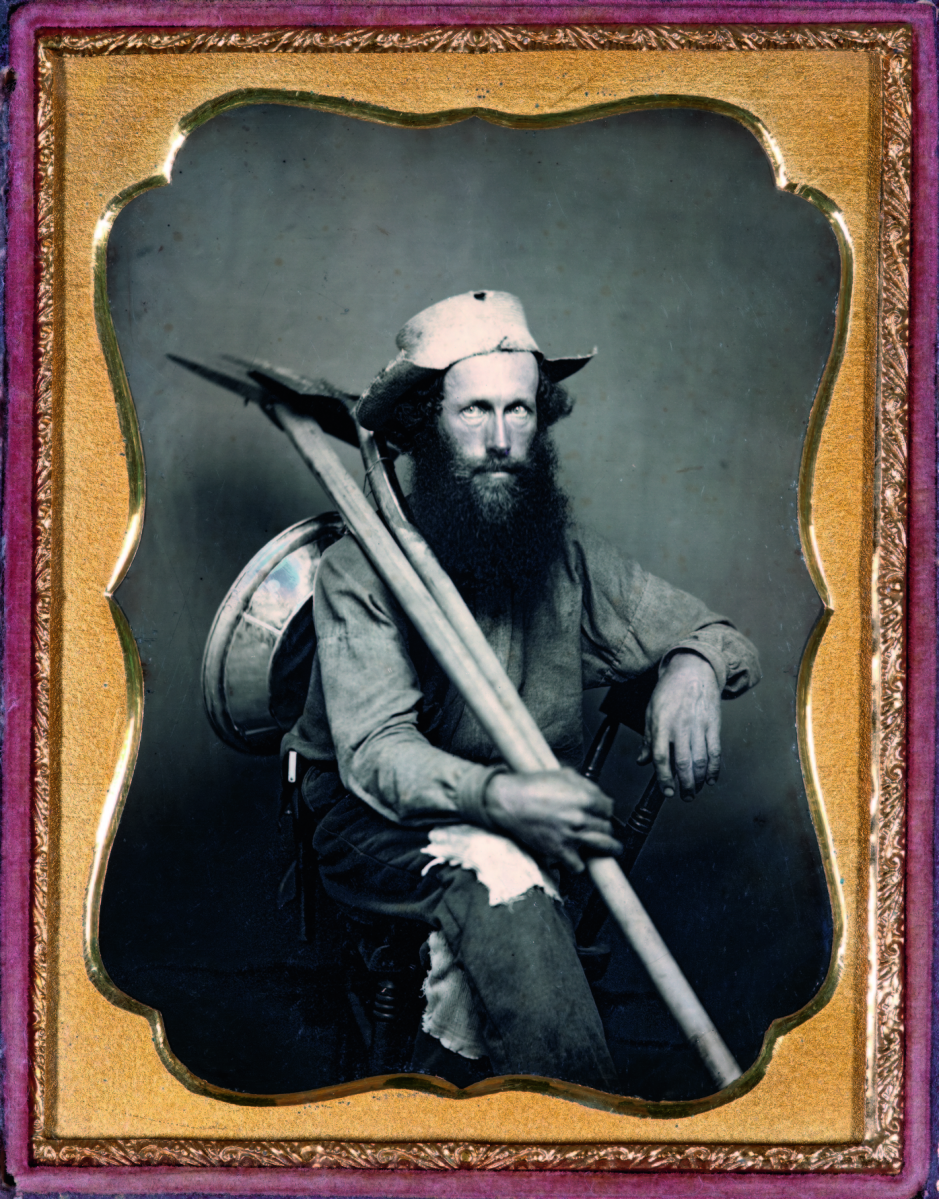

For viewers whose only miner image is drawn from old Yosemite Sam cartoons, the portraits of individual gold seekers will be a revelation. Where now we take selfies to show the world that we were really there, in the 1850s, having left behind families and taken great risks to travel to the West Coast, the men involved wanted a daguerreotype that recorded their involvement and even their success in this dangerous undertaking. They hold picks and shovels or pans with a bit of gold. Some have pistols to discourage robbery. Looking into their faces links our humanity with theirs. Some, thanks perhaps to period hairstyles, appear exotic, but others might be a high school teacher or local grocer. The curator remarks, “You can’t help but be drawn to the studio portraits of the miners holding the tools of their trade and dressed in their working attire. How important they thought it was to be shown as miners, they knew that they were participating in this epic event.”

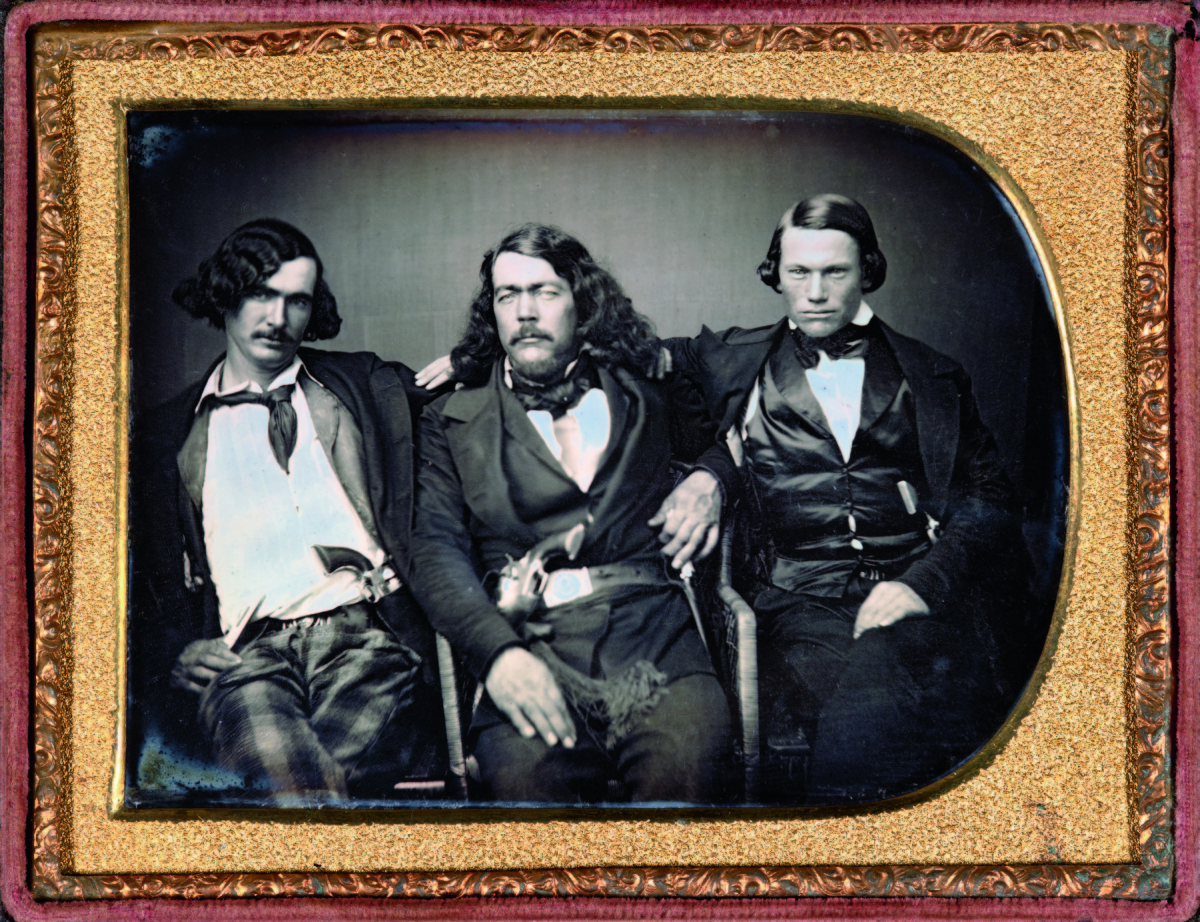

One of the most important exhibits is a multiple-plate panorama of San Francisco as it appeared in 1851, attributed to American daguerreotypist Sterling C. McIntyre (active 1844-1852). He also made single half-plate views of notable points of interest in the city, such as the harbor with its masted ships.

A second theme for the daguerreotypes in the exhibition is expressed in many images of prospectors actually working in the field, surrounded by their equipment. The techniques are discussed in a catalog chapter titled “‘Finding the color’: The Evolution of Mining Technologies.” An excellent example is a whole plate daguerreotype printed on the front endsheet, “Large Mining Operation at North Fork of the American River,” circa 1852, taken by George H. Johnson (1823-circa 1880s). The scene is filled with dozens of prospectors surrounded by rocks, water, wheelbarrows and devices. Two of the men have a girl child in tow, in an early example of Take-Your-Daughter-To-Work Day.

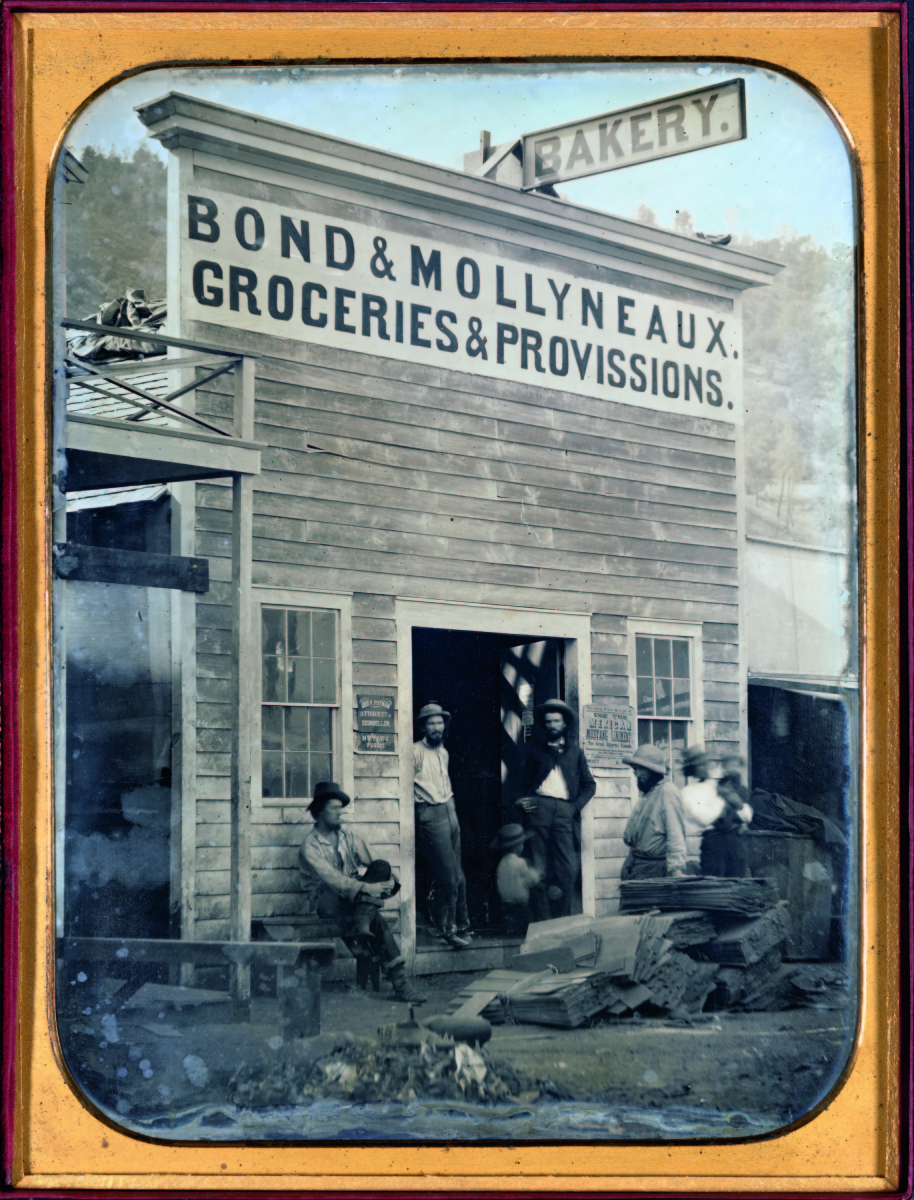

Equally interesting to historians are views of the small towns and camps where the workers bought supplies and food or tried to rest. Aspinwall comments, “That’s one of the advantages to covering this subject in a publication as well as in an exhibition. One thing that bothered me as I was getting these images together – how few showed non-white people or women or different races. If you looked at the pictorial record, you would think that the Gold Rush was just a white male experience, and, as we know, it clearly was not that.” Her chapter, “Diversity in the Gold Fields” discusses the role of African Americans and Asian immigrants in prospecting operations, illustrated with rare images.

She continues, “In the catalog, I explore [the question] why do we not have more of these images? And try to get to the heart of where were these people, and were they mining? The standard historical questions you would ask about participation in the Gold Rush. We know that women were in all of these gold towns, and a lot of them were the unsung entrepreneurs of this time period. If they were able to cook and clean, they were able to support themselves and send money home and, in some cases, to become quite wealthy providing these different domestic services to the miners. We don’t hear about that very often at all.”

Keith F. Davis, the senior curator of photography at the museum, contributed a chapter to the catalog on “The Urban Gold Rush: The Daguerreotype in San Francisco and Sacramento.” He writes about what the Gold Rush meant to the development of these cities: “Few of these new arrivals had any intention of staying in California – they aimed to strike it rich and return home… Nonetheless, in this fundamentally transient and exploitative endeavor, it was inevitable that something would stick. The money and people that did stay in the region gave rise to San Francisco, one of the nation’s most iconic cities, and Sacramento, the state capital.”

“Portrait of miner holding pan with gold” by unknown maker, circa 1852. Daguerreotype, sixth plate, 3¼ by 2¾ inches.

—Gift of the Hall Family Foundation.

The chapter is filled with view of the streets, shops and hotels as they appeared in the mid-Nineteenth Century as well as portraits of citizens who wanted their picture taken for posterity. In the former group is a panorama of San Francisco in 1851 created from five half-plate daguerreotypes, which is attributed to Sterling C. McIntyre (active 1844-1852). If you can mentally overlay the historical view on a Twenty-First Century map, you know the city well. Among the portraits is an image of “Captain Harry Love and his California Rangers,” circa 1853, by an unknown maker – three armed gentlemen one should not sit down beside in a bar.

Jane Aspinwall takes pride in the way the exhibits have been displayed for this show: “More times than not they’re put in a flat case with a single light on them. You’re moving around trying to see the image. Part of what I hope people would get out of this exhibition is how beautiful these early daguerreotypes are and how the early practitioners were not only technically proficient, but they had an aesthetic sensibility. When you have a group together, you can pick out stylistic differences.” In other words, they were accomplished artists, not just technicians.

She concludes, “With the California Gold Rush in particular, I would hope people would see similarities between what was going on in the Nineteenth Century and what goes on in the Twenty-First Century. A lot of the early issues – the ongoing debates about water rights, the fear of non-white immigration into California, the results of environmentally devastating mining processes like hydraulic mining and river mining – all these problems that arose so long ago are still issues in the West to this day. I think history is important.”

For anyone who would like to get a feel for the down-to-earth grubbiness of the period through a fictionalized presentation, try Robert Altman’s acclaimed 1971 “revisionist western” McCabe and Mrs. Miller, set in a mining community, although few real inhabitants would be as handsome and well-nourished as Warren Beatty and Julie Christie.

“Miners with cabin” by unknown maker, California, circa 1853. Daguerreotype, quarter plate, 3¼ by 4¼ inches. —Gift of the Hall Family Foundation.

“Golden Prospects” will be on view in Kansas City until January 26. Then it will travel to the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., from April 4 to July 12, and on to the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Conn., from August 8 to November 29.

For those interested in studying more images of women from this period, two ongoing exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC: “Women of Progress: Early Camera Portraits” through May 31 features major figures in the social movements of the 1840s and 1850s; and “Storied Women of the Civil War Era” through May 8, 2022, underlines the expanded role of women during the conflict that broke out in the decade after the Gold Rush.

For additional information, 816-751-1278 or www.nelson-atkins.org.

Photographs are from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo.