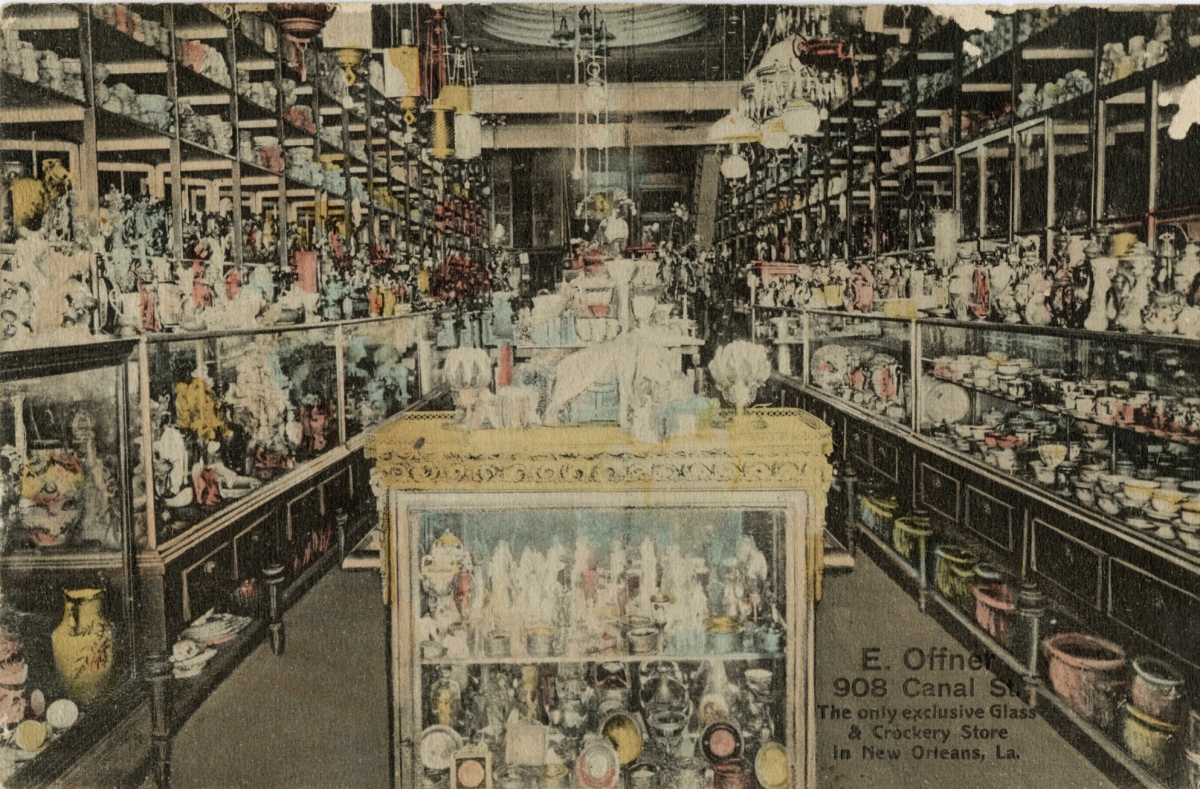

If ever a china shop dreaded the proverbial bull, it would have been E. Offner’s Glass & Crockery Store on Canal Street, shown here on a postcard issued circa 1910. Orderly showcase design fell by the wayside as the company strove to display its comprehensive selection.

By Karla Klein Albertson

NEW ORLEANS, LA. – Collectors often focus exclusively on an object’s materials and craftsmanship, leaving aside the question of where the buyer purchased the merchandise. In the Eighteenth Century, the wealthy might have commissioned personal and household furnishings directly from the maker, while ordinary folk simply produced their own necessities. By the Nineteenth Century, retail was on the rise. Rich and poor purchased goods from middlemen with an extensive selection of local and imported products.

Popular merchants of desirable furniture, decorative arts, clothing and jewelry were located in major cities. For the Gulf South – from Texas to Alabama to islands offshore – that city was the sophisticated metropolis of New Orleans. “Goods of Every Description: Shopping in New Orleans, 1825-1925,” an exhibition at the Historic New Orleans Collection through April 9, features more than 150 artifacts from the period. The exhibits include rare retail advertisements and documents as well as the actual goods sold by 32 city firms during that century.

The Historic New Orleans Collection is exceptionally well qualified to put together this show. It is unique in many respects, incorporating a museum, important research center with extensive archives, publishing house and several historic structures. Furthermore, its Royal Street exhibition galleries in the heart of the French Quarter are surrounded by the very streets where featured shopkeepers once opened their doors to the daily trade.

The exhibition was organized by curator Lydia Blackmore, who has been fascinated by the subject since her days in the Winterthur graduate program in American material culture. Touring the main gallery, she admitted, “This was my personal idea – retail history is something I’ve always been interested in. Why do people buy what they buy? I want to explore the history of the craftsmanship. The Nineteenth Century has such great stuff, but it’s not made in a tiny workshop. It’s made in a huge manufactory and shipped across the country to be sold in the South.” Outfitting the plantations and townhouses of the South created a tremendous demand. Firms in New York, Philadelphia and Cincinnati eagerly competed to supply the contents.

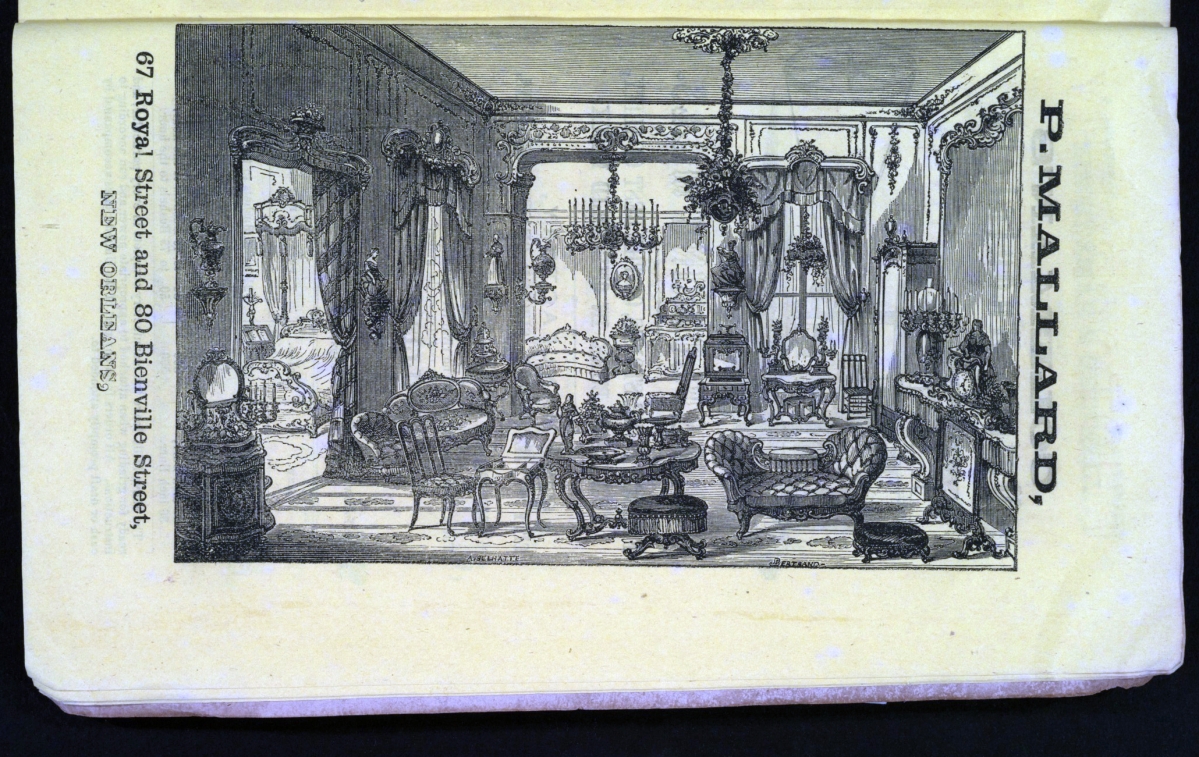

Blackmore continued, “I also did the show because I get a call about once a month from a nice person who says, ‘I have a Prudent Mallard bed and I know that he made it because it has an egg on it.’ Then I say, ‘Mallard didn’t make the bed, he imported it, and it’s actually an interesting story of economic history.’ In this whole show, only a few pieces were actually made here in New Orleans, but everything in the exhibition was originally sold here — we have a receipt or a mark. Mallard did have a staff of workmen, but they were putting together imported pieces and upholstering them for these New Orleans homes.”

Blackmore continued, “I also did the show because I get a call about once a month from a nice person who says, ‘I have a Prudent Mallard bed and I know that he made it because it has an egg on it.’ Then I say, ‘Mallard didn’t make the bed, he imported it, and it’s actually an interesting story of economic history.’ In this whole show, only a few pieces were actually made here in New Orleans, but everything in the exhibition was originally sold here — we have a receipt or a mark. Mallard did have a staff of workmen, but they were putting together imported pieces and upholstering them for these New Orleans homes.”

In the show, a massive armoire, which can be broken down into five sections for moving, is very similar to one at Rosedown Plantation in St Francisville, La. The curator speculated that the armoire might have been made in New York. She explained, “I did the exhibition, but I’m still learning a lot more about the exhibits. One of the things I’d like to research is just how much Mallard was importing from Cincinnati. These ‘Mallard beds’ that people bring to my attention – I think they may have been made by Mitchell & Rammelsberg.” The Crescent City has two major antiques auction houses where regional collectors pay a premium for local connections and provenance, Neal Auction Company and New Orleans Auction Galleries.

By the mid-Nineteenth Century, Royal Street was known as “Furniture Row.” An 1856 advertisement Mallard placed in De Bow’s Review depicts rooms crammed with every sort of furniture and decorative accessory available in its showrooms at 67 Royal and 80 Bienville Streets. Other major firms in the trade were Francois Seignouret, who made some furniture but imported more, and William McCracken, who did the same. The latter was importing dozens of beds from a firm in Manchester, Mass. Far too large for Massachusetts houses, they were made specifically for the high-ceilinged interiors of the South.

On the practical side, New Orleans had purveyors of the glass, china and silver necessary for large-scale entertaining during the Mardi Gras and holiday seasons. Objects for the table could be purchased from a firm like Hill & Henderson on Canal Street, which imported dishes, glasses and silverplate from England and Europe. Silver services were also available from jewelry stores, which frequently also sold small decorative pieces and clocks. The 2016 New Orleans Antiques Forum at the Historic New Orleans Collection, “Dinner is Served: Decorative Arts and Dining in the South,” proved especially popular with scholars and collectors. Blackmore noted, “It sold out in two days and everyone really enjoyed it. People are coming to New Orleans to hear about antiques, but also to go shopping and eat good food and have a party. We always have a festive opening reception here and leave time to visit the antiques stores.”

The main gallery features a rosewood overmantel mirror, circa 1860, retailed by French-born importer Laurent Uter and a massive mahogany armoire from the shop of Prudent Mallard, active 1838 to 1874.

The production and sale of silver in New Orleans, a complex subject, is still awaiting the completion of a definitive publication that will be issued in the future by the institution. While many firms actively imported silver from firms on the East Coast and abroad, silversmiths also lived and worked in New Orleans, setting up their own workshops or filling orders from retailers. In the first decades of the Nineteenth Century, French or French-Caribbean makers such as Jean-Noel Delarue and Louis-Gabriel Couvertie executed simple flatware and small items. Any lot with their mark brings a premium in the antiques market.

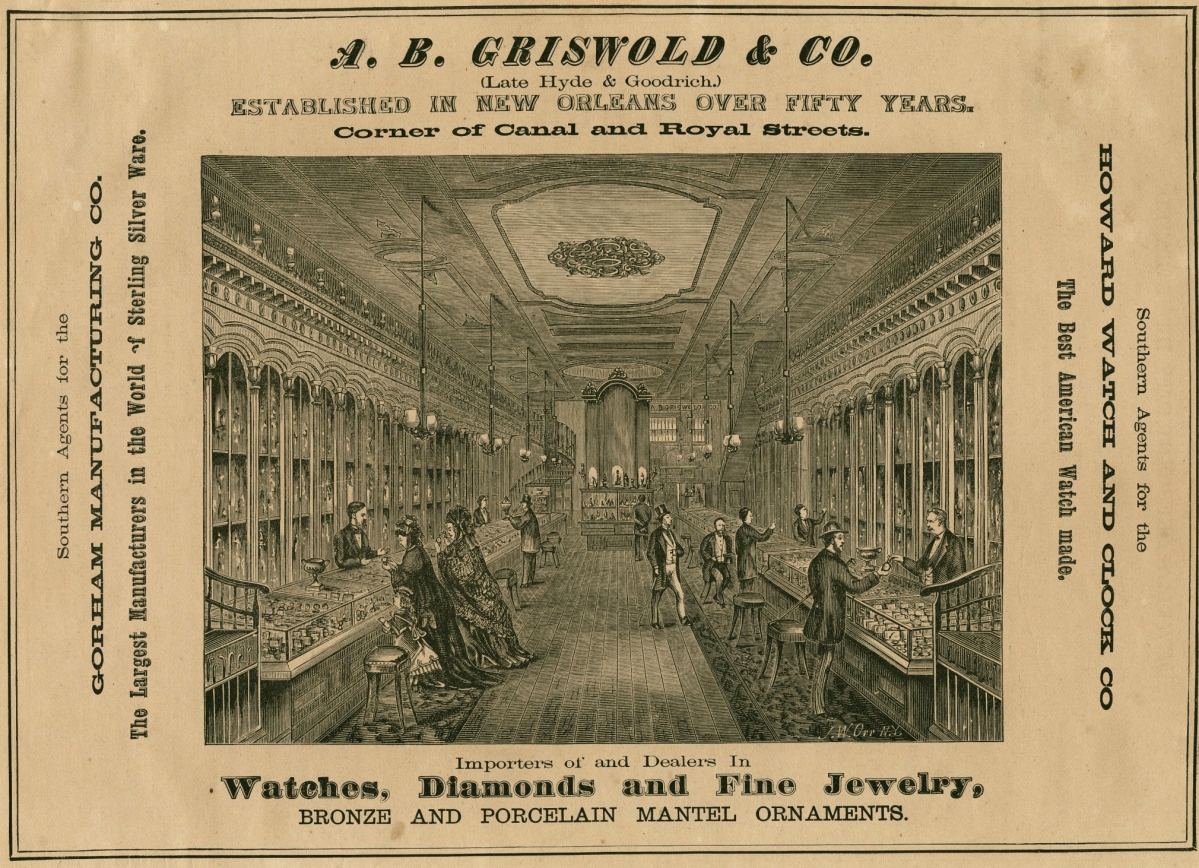

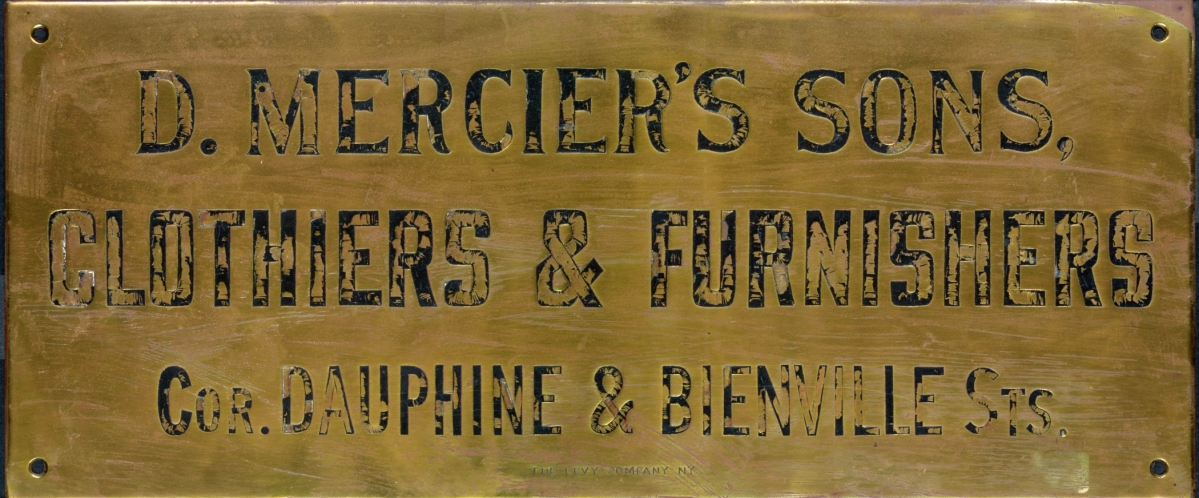

Collectors also seek out the later work of the German-trained Adolphe Himmel, who notably made fine rococo hollowware for the major retailer Hyde & Goodrich. By the time of an 1857 advertisement in New Orleans Merchants’ Diary and Guide, the store at the corner of Canal and Royal Streets sold jewelry, watches and gold and silver wares along with guns and pistols. E.A. Tyler, who retailed several pieces in the show, began as a watchmaker, then expanded to sell jewelry, silver, music boxes and even pianos.

Perhaps the most impressive object in the exhibition is the highly detailed coin-silver model of a streetcar, made between 1865 and 1870 as a demonstration of the silversmith’s skill by the Zimmerman firm on Canal Street. The roof is removable so visitors can view the seats within and the tiny louvered windows that open and shut. Support from the Laussat Society allowed the Historic New Orleans Collection to purchase the artifact in 2015 when it sold at Neal’s Louisiana Purchase Auction for $43,325. The curator said, “This is an exact copy of the mule-drawn streetcars that were going up and down Canal. I think that it was either a prize for a fair or a retail window display piece.”

The Maison Blanche department store building on Canal Street, shown here in a 1924 photo, still exists as part of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in the Central Business District.

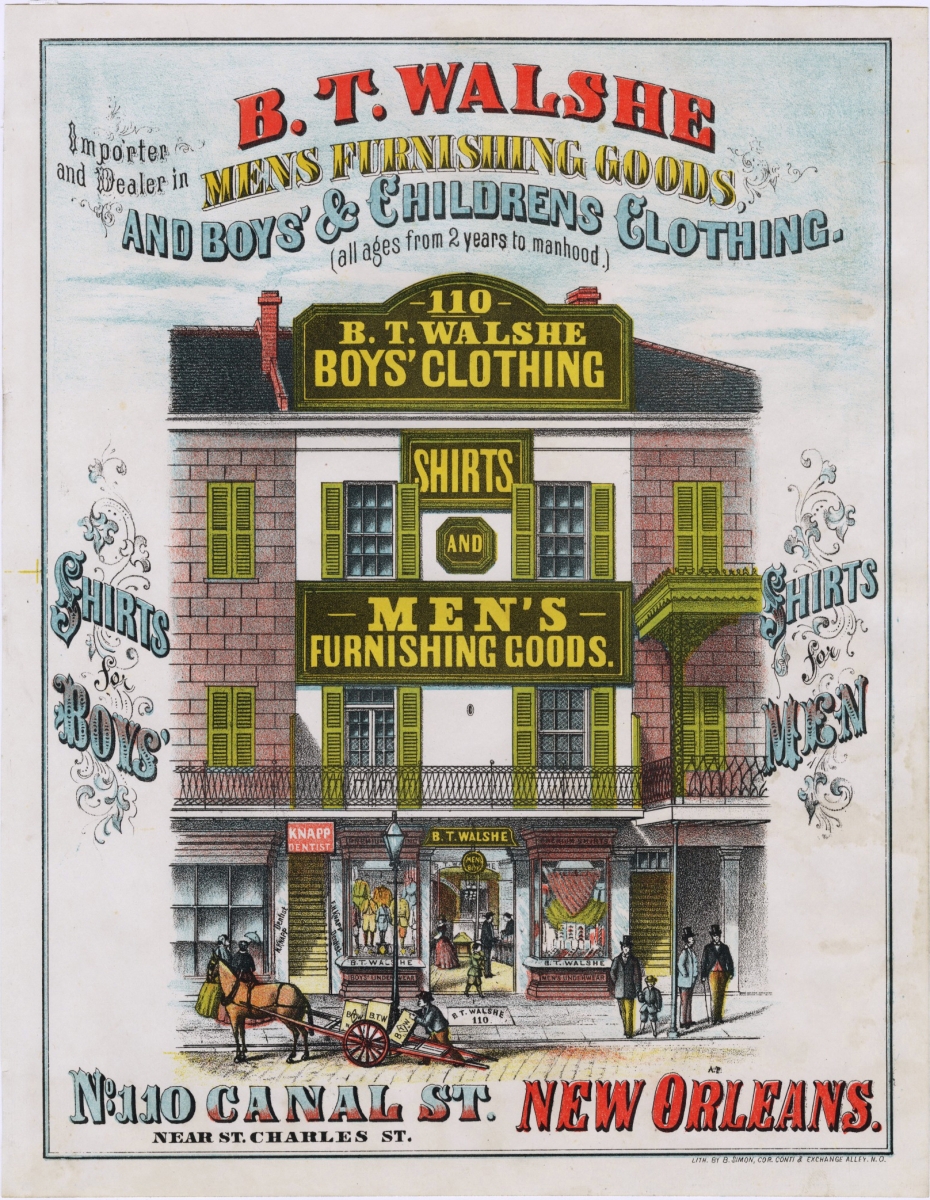

Shoppers, confined to distant plantations for most of the year, wanted to shop for more than silverware and soap. Where to find new dresses, tailored suits and fancy hats merits a special section in the show. Madame Olympe Boisse owned a fashionable millinery and dry goods store on Chartres Street in the Quarter. She carried the latest ball dresses imported from Paris, into which she stitched her own exclusive label. The less selective could buy a stylish gown from a large store such as D.H. Holmes. A green dress of circa 1885 graces a mannequin in the exhibition.

The shopping history of the city concludes with the rise of the modern department store in the early Twentieth Century, as Godchaux’s and Maison Blanche joined Holmes as one-stop emporiums for every sort of merchandise. Lydia Blackmore said, “Canal Street became a major shopping destination, the widest street in the country. We had a lecture in December about Christmas shopping on Canal – people get into the nostalgia and fond memories of going there with their parents.”

Today, a traveler may not come to New Orleans to buy a dresser or a ball dress, but to acquire antiques and the vibrant historical background from which they emerged. The Centennial of 1876 may have been celebrated in Philadelphia, but New Orleans had a well-established trade in antiques by the last quarter of the Nineteenth Century. Furniture sold off in desperate times returned to Garden District townhouses and outlying plantations. As Blackmore wrote in conclusion, “The antiques stores in New Orleans carried on the legacy of retail and shopping established by earlier retailers. To meet local demands, they imported antiques from Europe and the Northeast, selling them alongside the pieces that had been passed through generations after having been purchased originally on the shopping thoroughfares of Old New Orleans.”

The Historic New Orleans Collection is at 533 Royal Street. For more information, 504-523-4662 or www.hnoc.org.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.