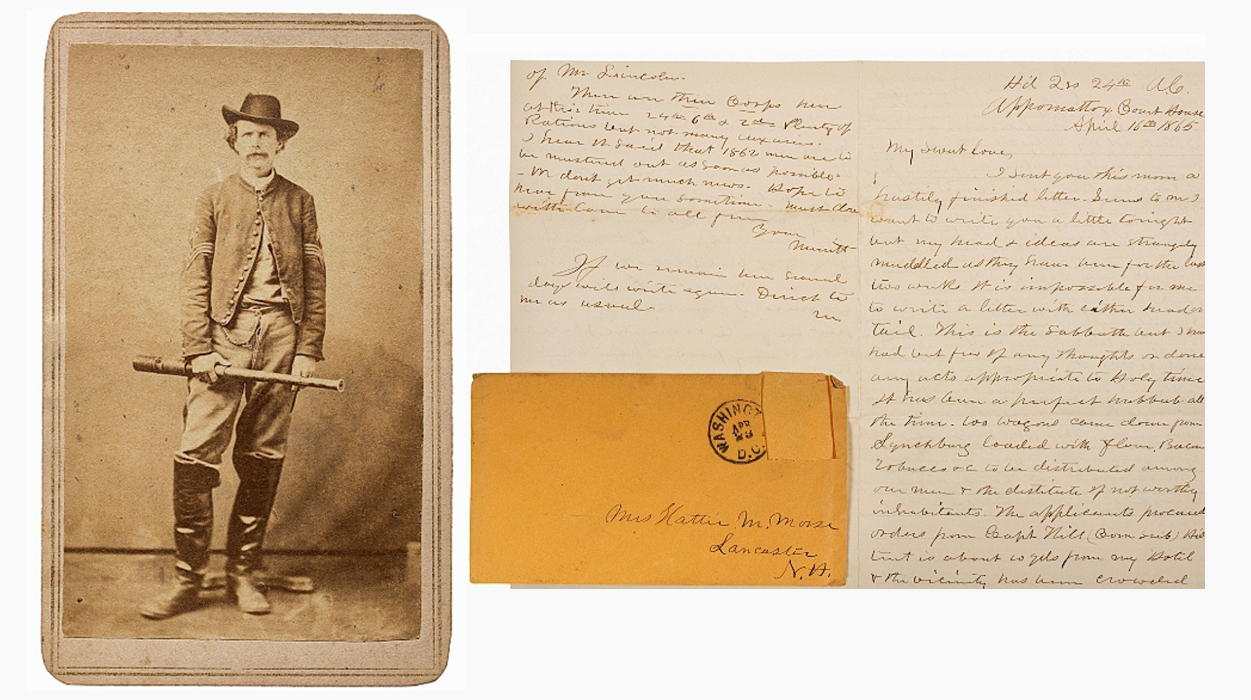

The sale’s top lot was a 1,000-page archive from Civil War soldier John Merritt Morse, consisting of 145 letters; 11 portrait CDVs of identified soldiers; a leather wallet; a small printed Army of Northern Virginia battle flag; an issue of The New South published out of Port Royal, S.C.; and Morse’s Civil War-era Lemaire field glasses. An institution bought the archive for $53,125. It was notable in that it detailed the lives of the newly emancipated African Americans of the Sea Islands, South Carolina, who took part in the US Government’s “Port Royal Experiment,” its first effort to build and support a community of freed men and women during the Civil War. It was also notable for its documentation of the Signal Corps, units who relayed communications during Civil War battles, where material is particularly scant. Specialist Katie Horstman said that Morse was very well-written and thorough in his records, providing a full picture of the soldier’s experience in the Civil War from October 1862 to June 1865.

Review by Greg Smith, Catalog Photos Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions

CINCINNATI, OHIO – Cowan’s June 26 American Historical Ephemera and Photography sale grossed $785,887 on 383 lots.

“I think the sale was a resounding success,” said auctioneer Wes Cowan, who called the auction from a laptop at his home in Michigan.

“We’re continuing to see growth with new consignors, new bidders and new buyers throughout the pandemic,” he said. “I think our story is no different than any other mid-market auction house. We’re experiencing pretty good times in spite of the fact that we can’t have a live auction.”

This sale, which Cowan began holding in one form or another 25 years ago, was filled with history, each lot a short – sometimes long – visual paragraph of the tale recounting America’s earliest beginnings through those who lived it. Some are palatable, others go down hard, but they are all honest and true.

Interest is high in the material, with the auction selling at 87 percent by lot. Cowan said that its driven by both private buyers and institutions.

Six of the top ten lots in the sale were bought by institutions. The material covered the African American experience, the Civil War era, life in the American West, American involvement in World War II and others.

Among the institutions, Cowan noted that historical material is being collected in volume by smaller state museums or those with a local and regional focus. The encyclopedic museums already have significant holdings and are working to fill in the gaps on a situational basis.

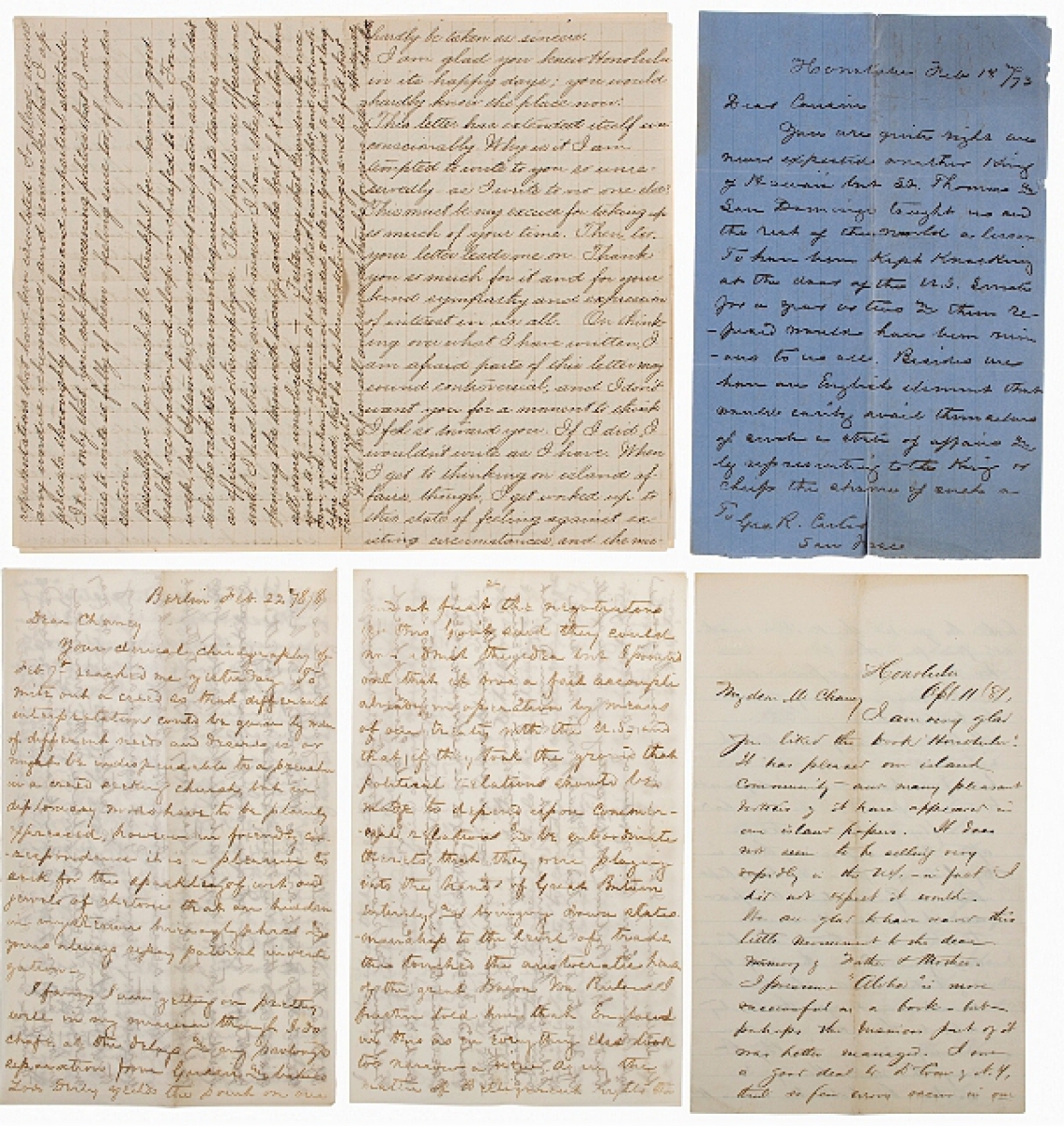

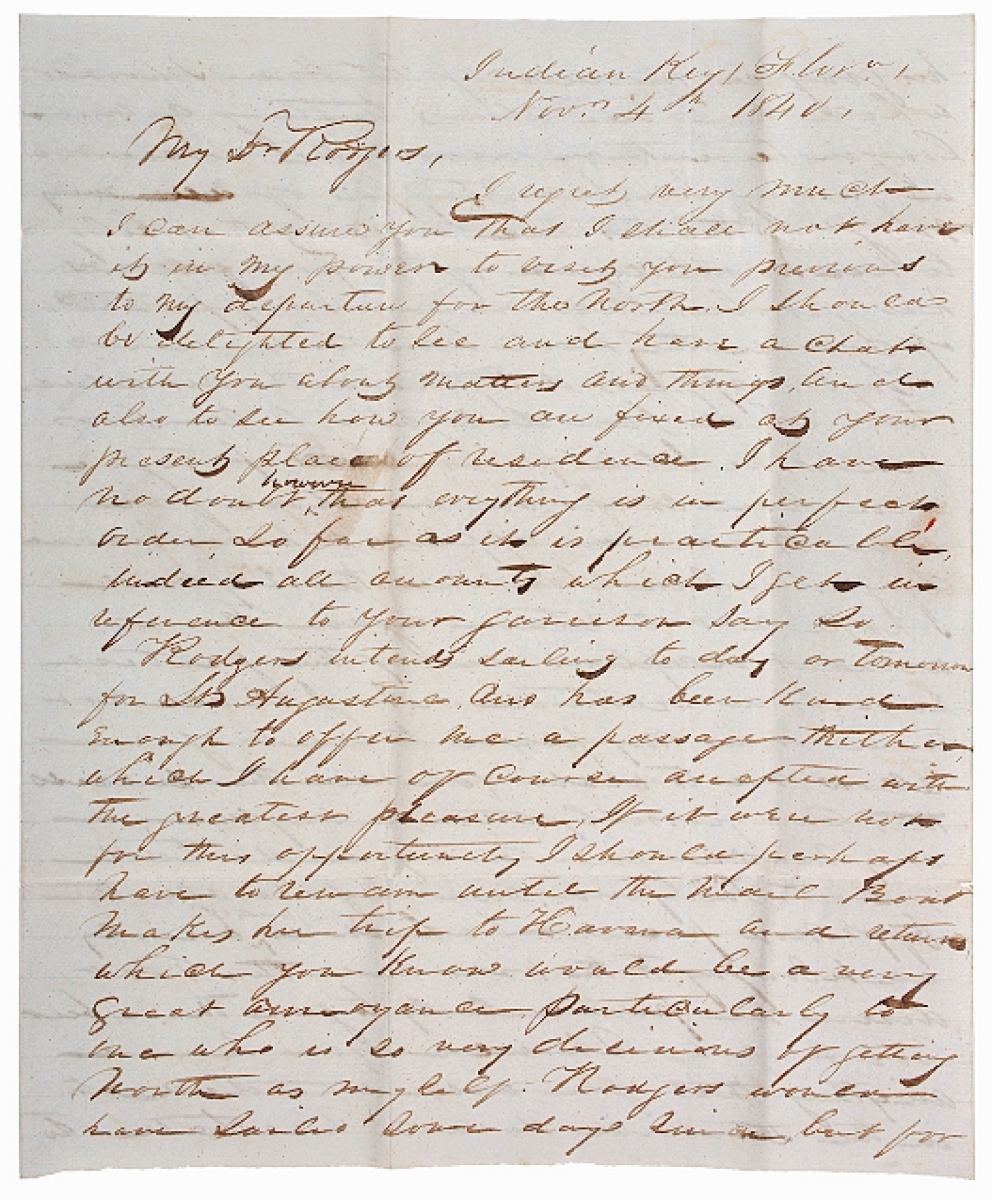

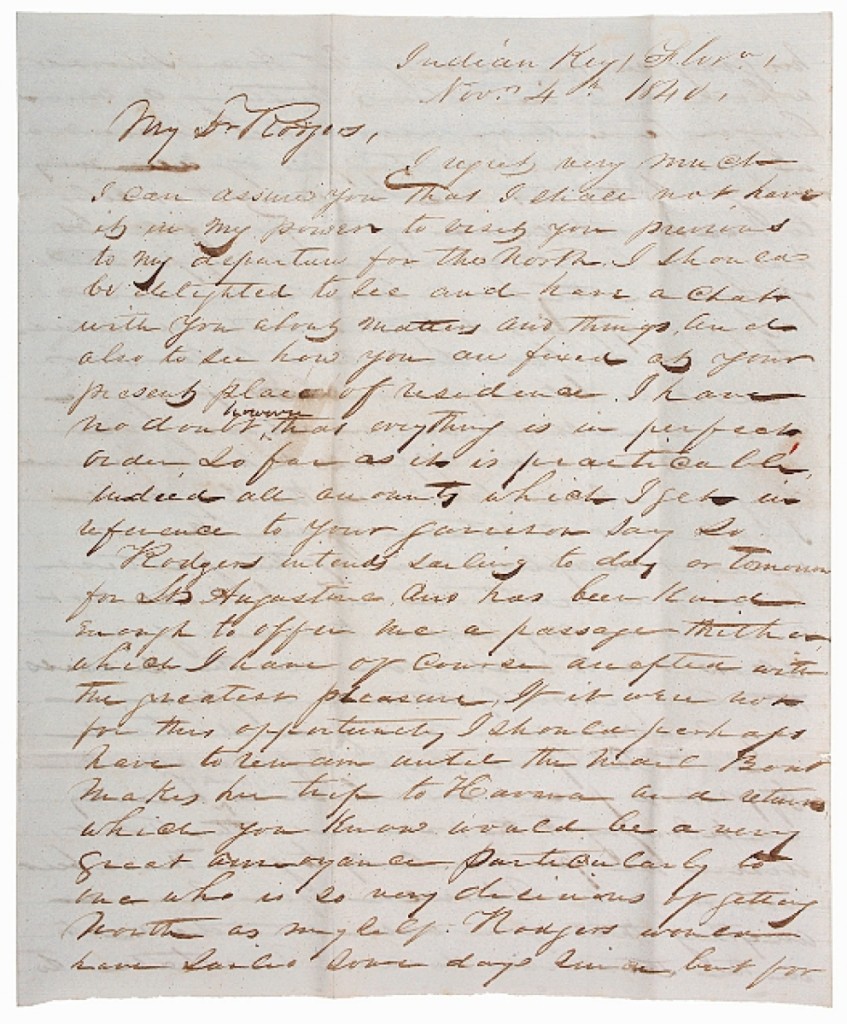

Selling to an institution for $36,250 was this archive from prominent Rear Admiral Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers (1819-1892). It featured 320 letters. The Admiral came from the Rodgers and Perry families, and was related by marriage to the influential Slidell family of Louisiana. He was the son of Captain George Washington Rodgers (1787-1832) and Anna Maria Perry (1797-1856), nephew to Com. Oliver H. Perry and Com. Matthew C. Perry, and grandson of Capt. Christopher Raymond Perry and Com. John Rodgers. The archive spanned from the 1840s to 1880s and covered the admiral’s time in the Mexican War, Indian War and Civil War.

“If we have something that’s relative to Oklahoma or Texas, we can expect the institutions in those states to bid, whereas an institution in Ohio might not bid. There’s no one institution that’s snapping up everything,” he said.

An institution nabbed the sale’s top lot: a 1,000-page archive from Civil War soldier John Merritt Morse, who served in the New Hampshire 3rd Infantry and later the United States Army Signal Corps. It doubled estimate to sell for $53,125. The archive featured more than 145 letters, many four to eight pages long and dating from October 1862 to June 1865. Most of them were written to Morse’s wife, Harriet “Hattie” Lord Morse.

On the archive, Katie Horstman, senior specialist of American Historical Ephemera and Photography at Cowan’s, said, “Morse was well-written and very detailed, and the archive discussed good subject matter. It covers his entire Civil War service record. With other correspondence archives, you sometimes get a glimpse of one moment, but this covered it all.”

Among the descriptions he provides are those of the freshly emancipated African Americans of the Sea Islands, off the coast of South Carolina, and the “Port Royal Experiment,” the United States government’s first efforts to build and support a community of freed men and women during the Civil War.

Signal Corps material drove interest further, as the dearth of it on the market, or in existence, creates demand. “They were a specialized unit,” Horstman said. “There weren’t as many people who served in the Signal Corps. They were in charge of the communication and signal systems, they played such a crucial part in the war. It’s a unique part in the armed services – a huge factor in the battles.”

The archive had descended in the family of the consignor, who had transcribed every page.

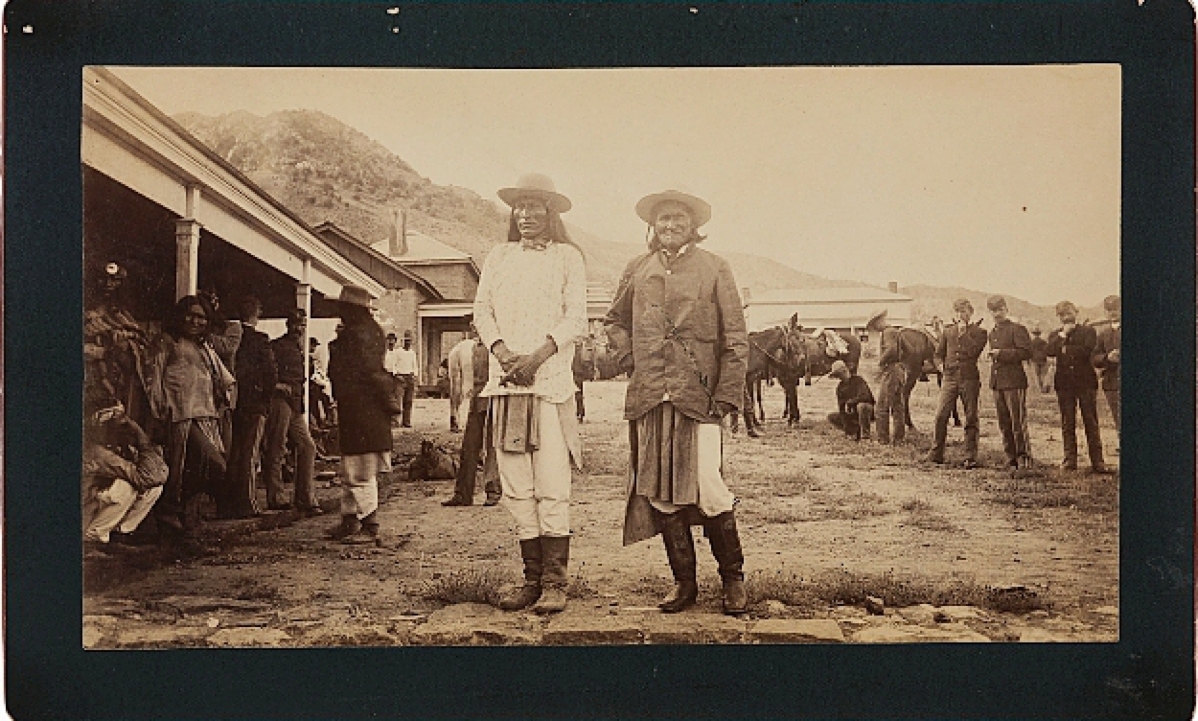

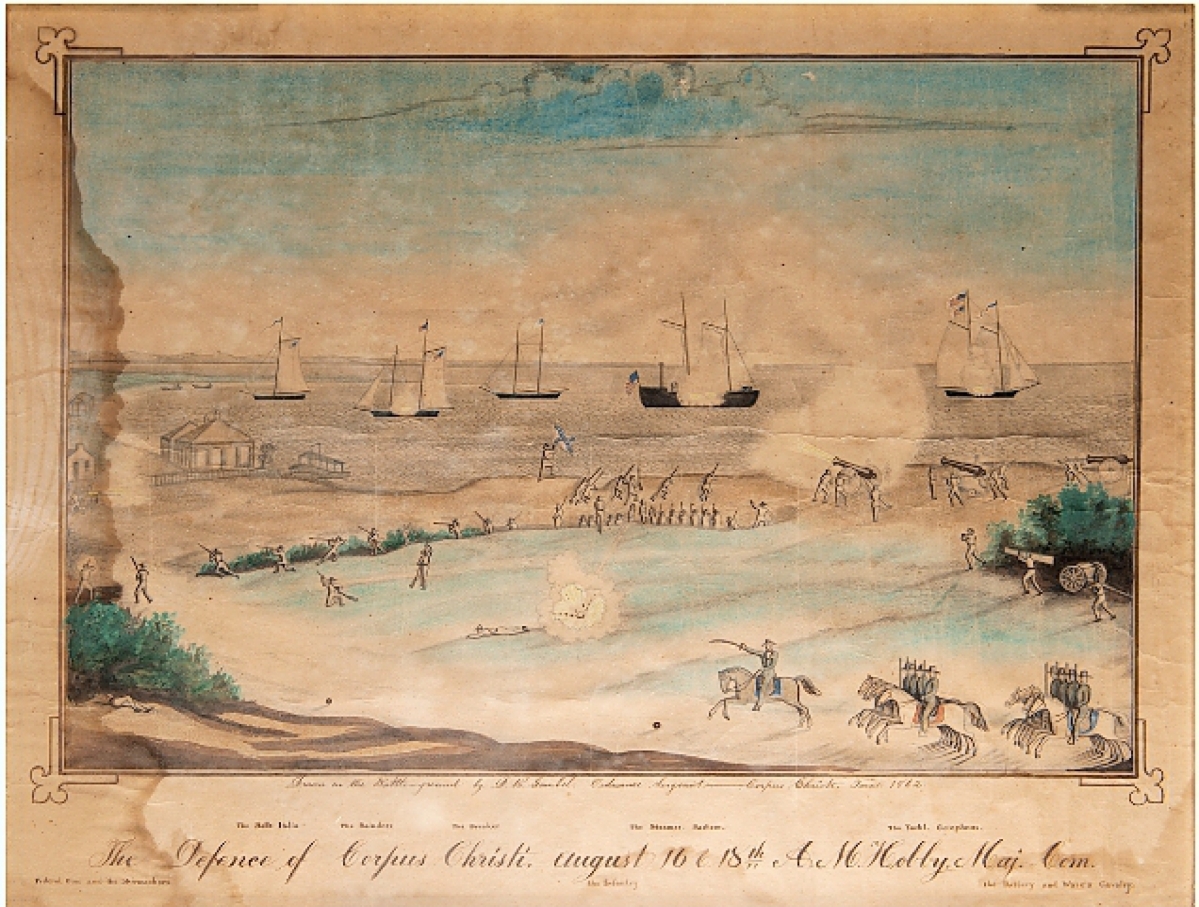

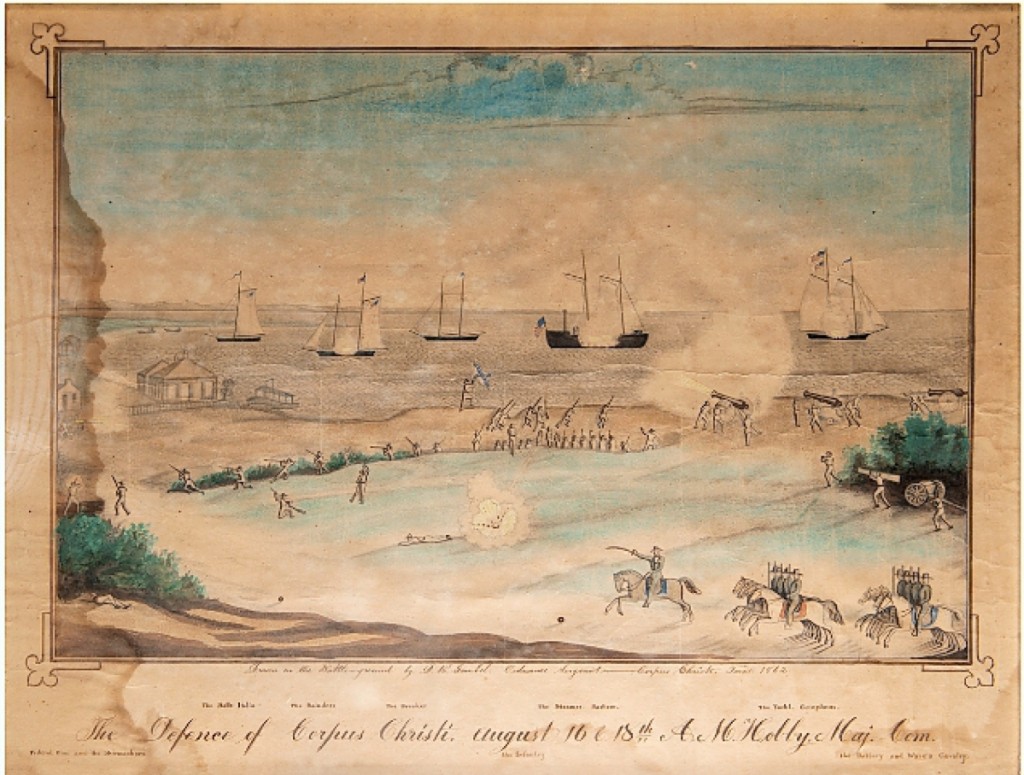

Texas bidders did not want to let go of this watercolor depicting the Battle of Corpus Christi, which sold for $32,500 on a $4,000 estimate. It came by descent from the family of Captain James A. Ware (1826-1910), Co. F, 1st Texas Cavalry, who is depicted and labeled in the work with his unit as “The Battery and Ware’s Cavalry.” It was produced by 1st sergeant D.R. Gamble.

Coming in behind at $36,250, also selling to an institution, was an archive of 320 letters, most addressed to Rear Admiral Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers (1819-1892). Cowan’s wrote that the admiral came from two of the most distinguished families in the history of the US Navy, as he was the son of Captain George Washington Rodgers (1787-1832) and Anna Maria Perry (1797-1856), nephew to Com. Oliver H. Perry and Com. Matthew C. Perry, and grandson of Capt. Christopher Raymond Perry and Com. John Rodgers. The correspondence includes over a dozen members of the Admiral’s families, as well as Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, Rear Admiral Samuel F. DuPont, Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren and Admiral David Dixon Porter. The archive spanned from the 1840s to the 1880s, detailing his time in the Mexican War, Indian War and Civil War.

“It’s Texas,” Wes Cowan replied, when asked why a Civil War watercolor depicting the Battle of Corpus Christi sold for $32,500 on a $4,000 high estimate. “Those Texas buyers are like snapping turtles. Once they get a hold of something, they won’t let it go.” The work, by Nineteenth Century 1st sergeant D.R. Gamble, depicts the different features of that battlefield, all labeled, including “Federal Gun and the Skirmishers,” “The Infantry” and “The Battery and Ware’s Cavalry,” as well as the five Union Navy ships involved in the battle: The Belle Italia, The Reindeer, The Breaker, The Steamer Sachem and The Yacht Corypheus. The watercolor comes by descent from the family of Captain James A. Ware (1826-1910), Co. F, 1st Texas Cavalry, who is depicted in the work and a documented participant in the conflict.

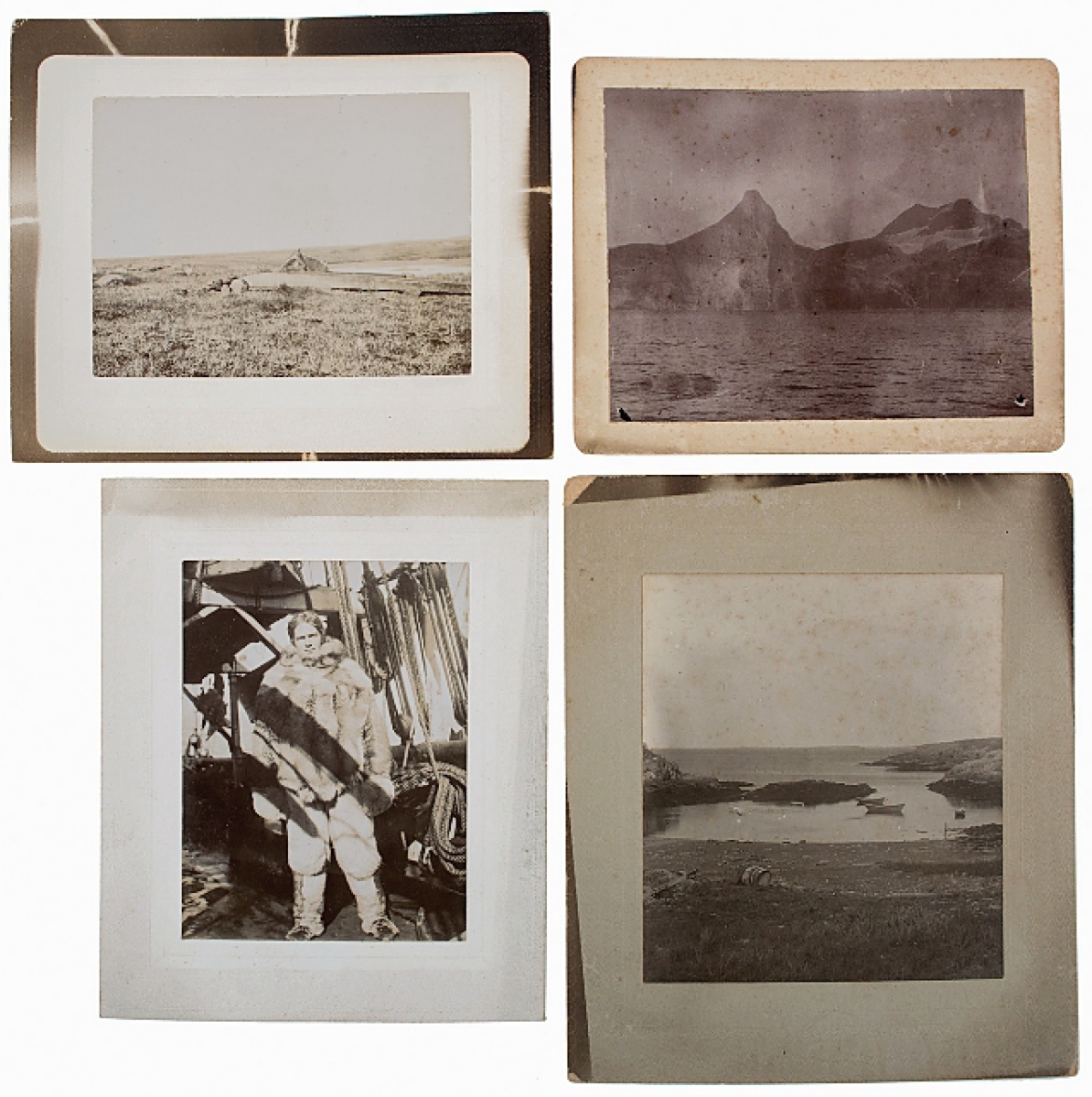

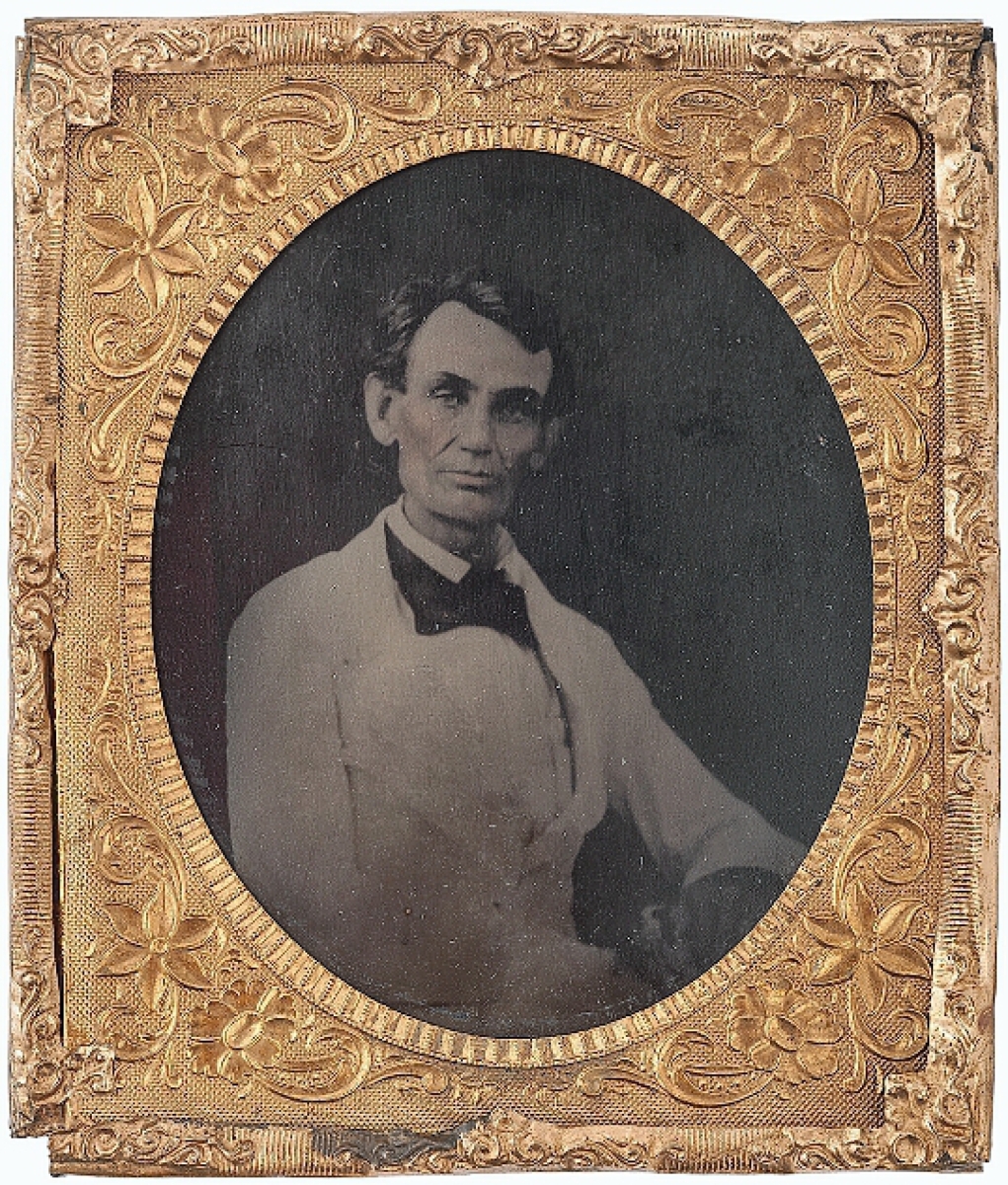

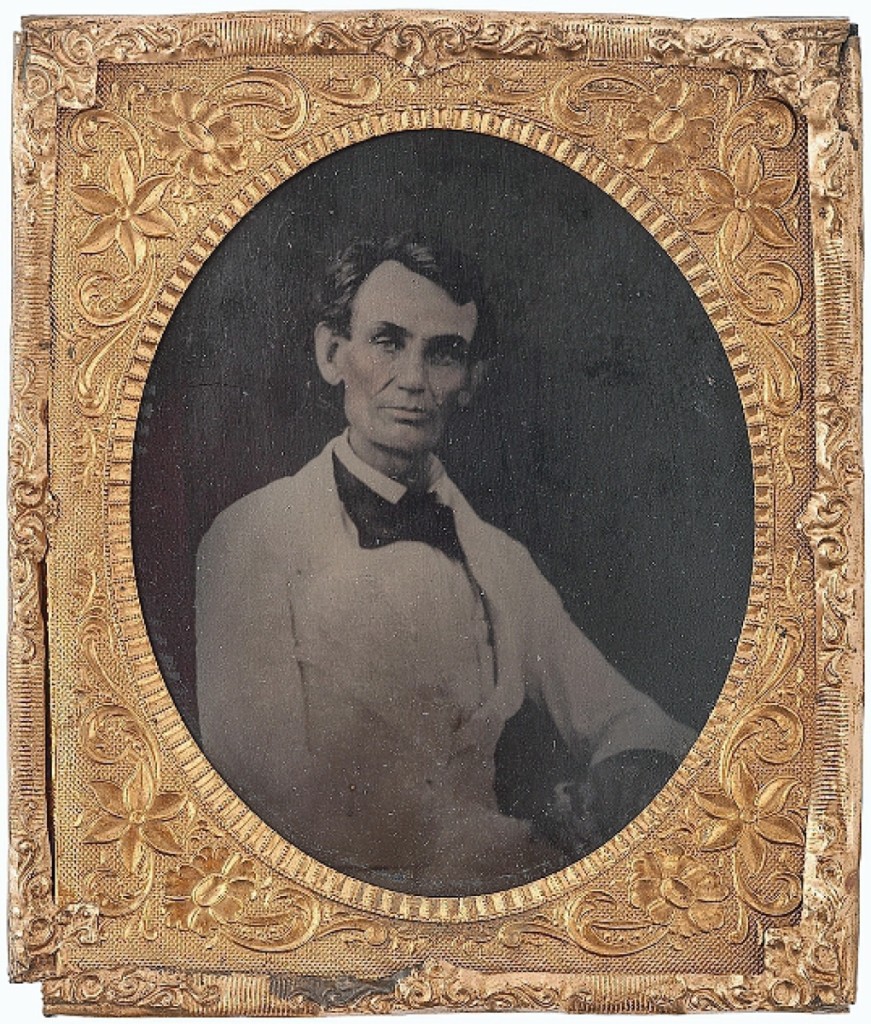

Early photography featured prominently in the sale. Wes Cowan said his favorite work was a sixth plate tintype of Abraham Lincoln titled the “Beardstown Portrait.” It brought $18,750. “It’s the only one I’ve ever seen in 30 years of doing this,” Cowan said. “Lincoln’s portrait was copied many times, but this particular tintype of him wearing this white linen suit, as a beardless and relatively young man – there’s only one other image known that exists, the original ambrotype at the University of Nebraska. It’s an incredible rarity that had a great collection history.” The tintype was taken by 18-year-old Abraham Byers in Beardstown, Ill., on May 17, 1858. It is the only extant period copy known. The catalog noted that Lincoln was in Beardstown defending Duff Armstrong in what would become known as the “Almanac Trial.” Armstrong had been accused of murdering a man at night by a witness who claimed to have seen the event unfold from 150 yards away. Lincoln produced an almanac to prove it was a moonless night and thus the witness could not have seen the event from that far away, which rendered a not-guilty verdict. An account from Byers states that he found Lincoln after the trial and asked to take the picture, leading him back to his studio. The tintype copy descended in the family of Willard Mayberry (1902-1959), a Kansas newspaper publisher. According to the family, it “had always been in the family lockbox, kept in an envelope from the Seattle studio of famed photographer Edward S. Curtis, which bears the inked notation: ‘For Willard Mayberry Elkhart, Kansas.'”

Also in the envelope was a newspaper clipping from the February 24, 1926 issue of the Portland Oregonian, which said the tintype was a prized possession of Mabel Darling of the Roosevelt Hotel, who received it from her father, Sergeant Thomas Lawrence Byrne, who served in Company B of the 11th Massachusetts.

Another object Cowan liked, and which also had a newspaper angle, was an abolitionist ribbon memorializing Elijah Parish Lovejoy (1802-1837), which sold for $3,375. After graduating from what is today known as Colby College, Lovejoy moved in 1827 to St Louis where he became involved with the Missouri abolitionists. He left in 1833 to become a Presbyterian minister, and returned to St Louis a year later, where he edited the St Louis Observer. He ran editorials critiquing the Catholic Church, liquor, tobacco and slavery, which did not sit well with the denizens of St Louis, who destroyed his press three separate times. He moved to Alton, Ill., a pro-slavery town in a free state. Not long after his move there, a pro-slavery mob formed and attacked his printing warehouse, burning it down and murdering him with a shotgun. They then threw the press into the Mississippi River. Cowan said, “It’s a ribbon that no one has ever seen before, just an incredible rarity. One of those fun things that, in this business, just when you think you’ve seen everything, there’s something else that’s brand new that provides a new perspective on an important person and important period of American history.”

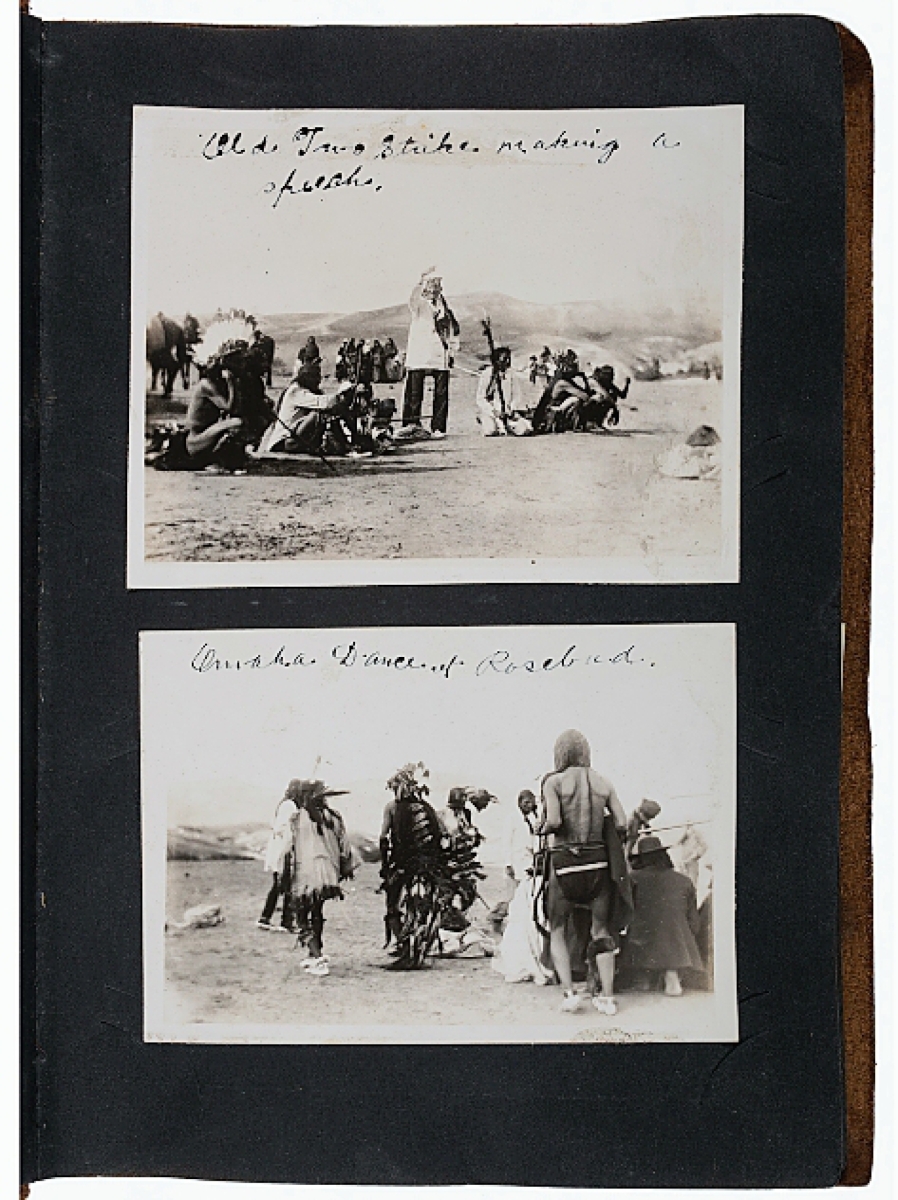

Specialist Katie Horstman said she could find only one other example of a Curtis print with a red signature, and that description said it was made for an exhibition. That detail could have been the reason that this platinum photograph of “Three Chiefs, Piegan,” sold for $21,250 on a $3,000 estimate. “It’s a beautiful scene in original frame with original backing,” Horstman said, adding that the consignor had purchased it from the estate of descendants of a Massachusetts Civil War officer.

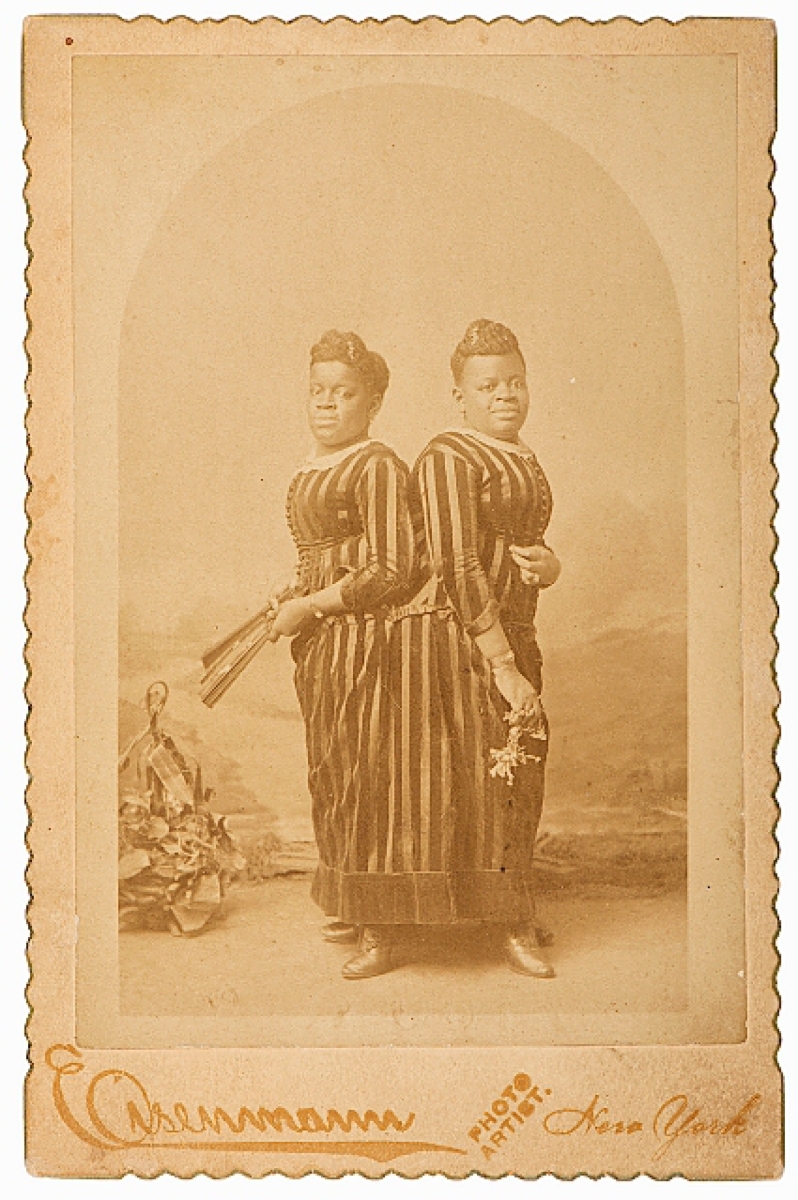

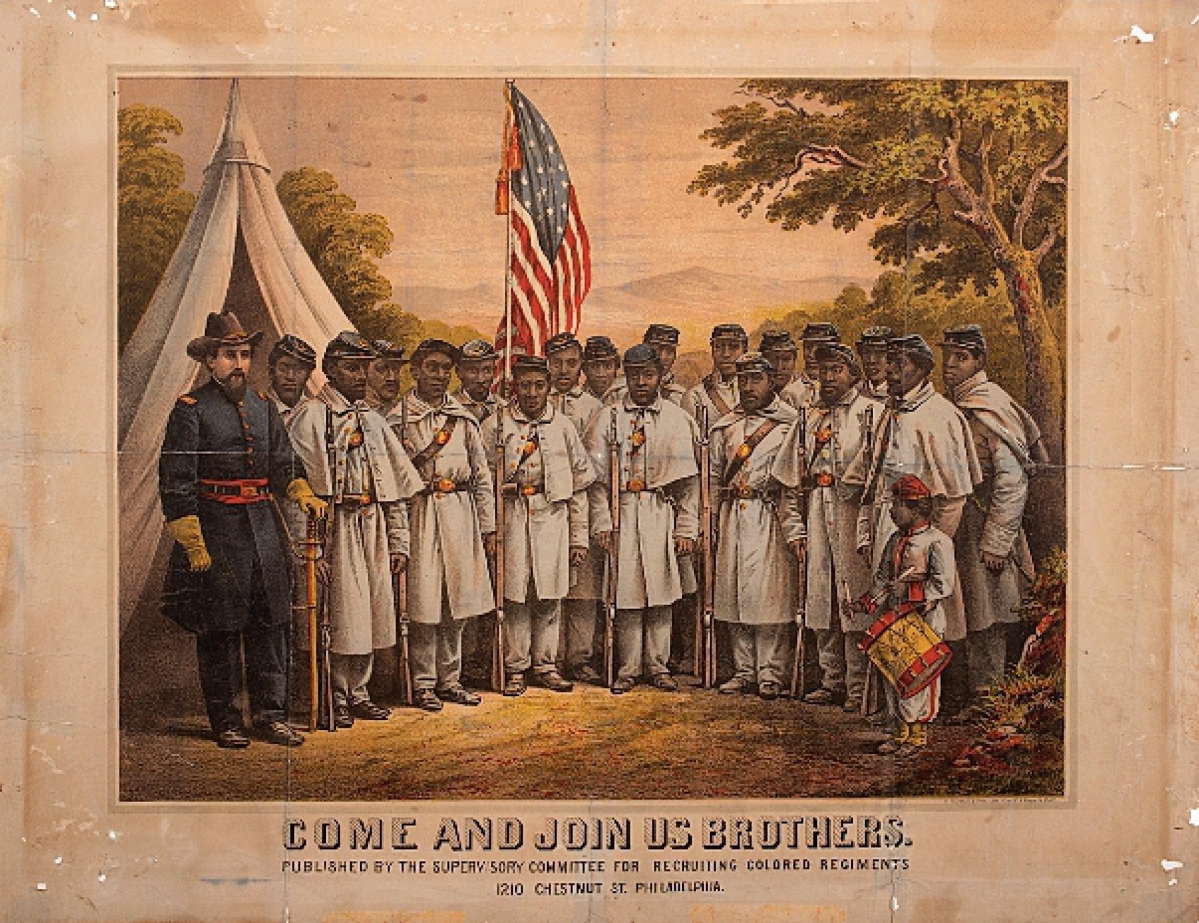

Cowan said interest in African Americana has seen an uptick in recent years. “It was relatively small 25 years ago, but it has steadily increased. Not only among institutions, that ignored it for many years and now recognize it as significant to their holdings, but also to private collectors. They are making aggressive efforts to collect it.”

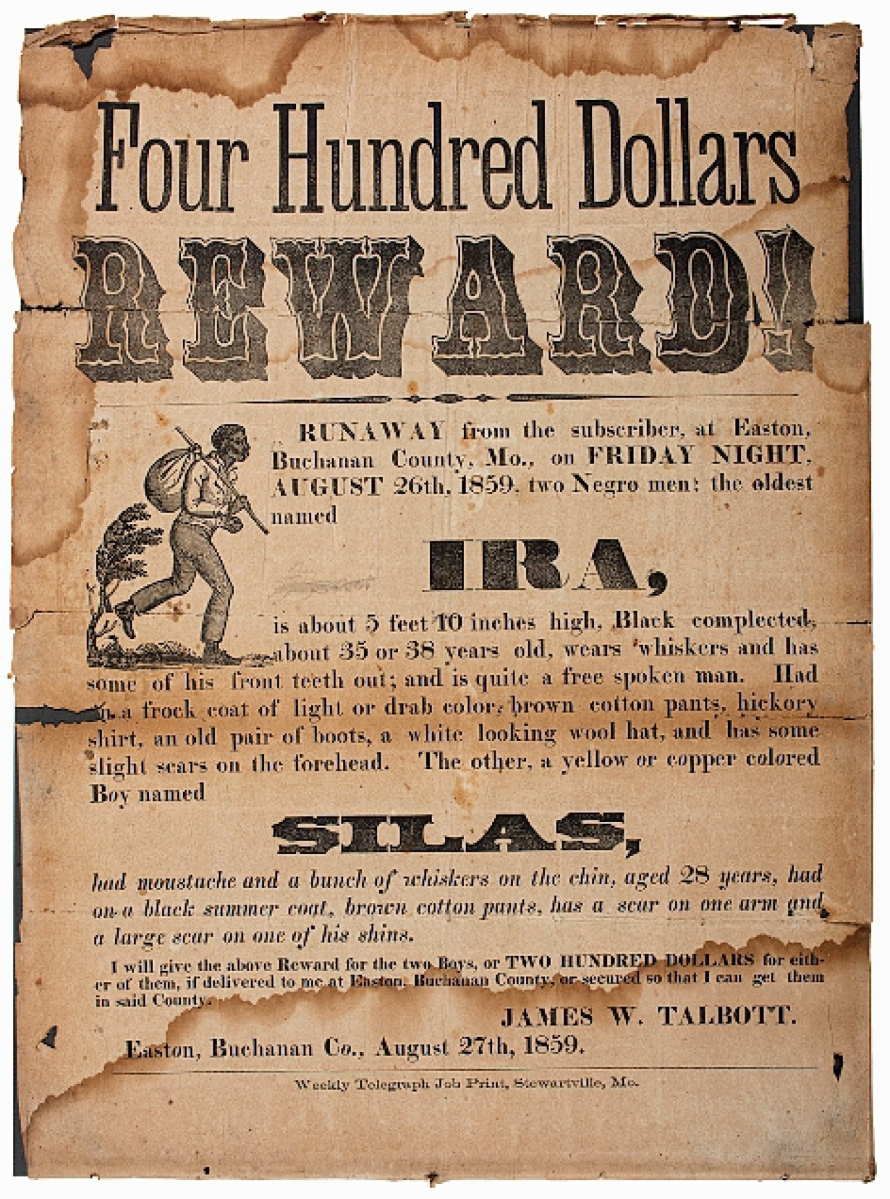

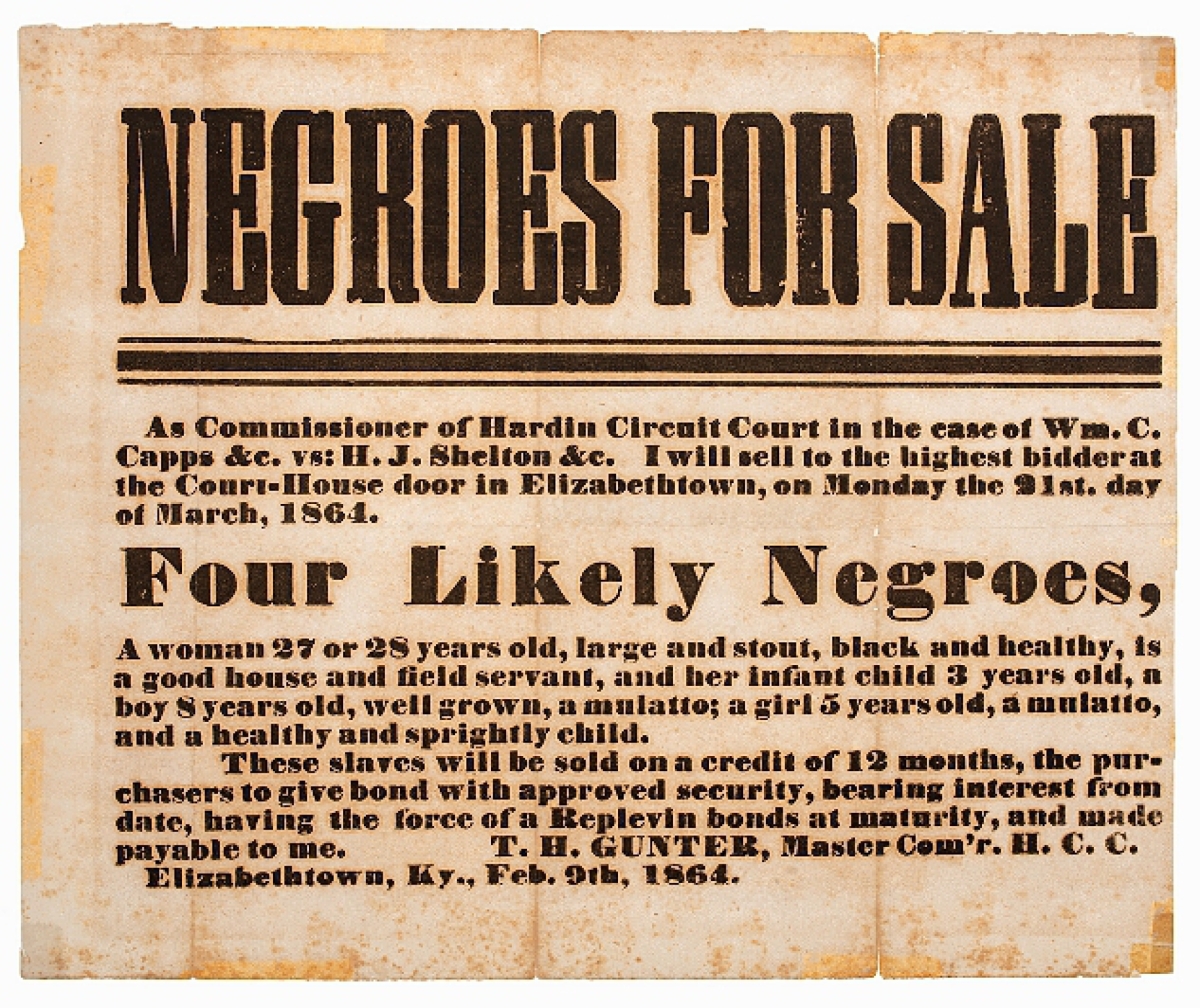

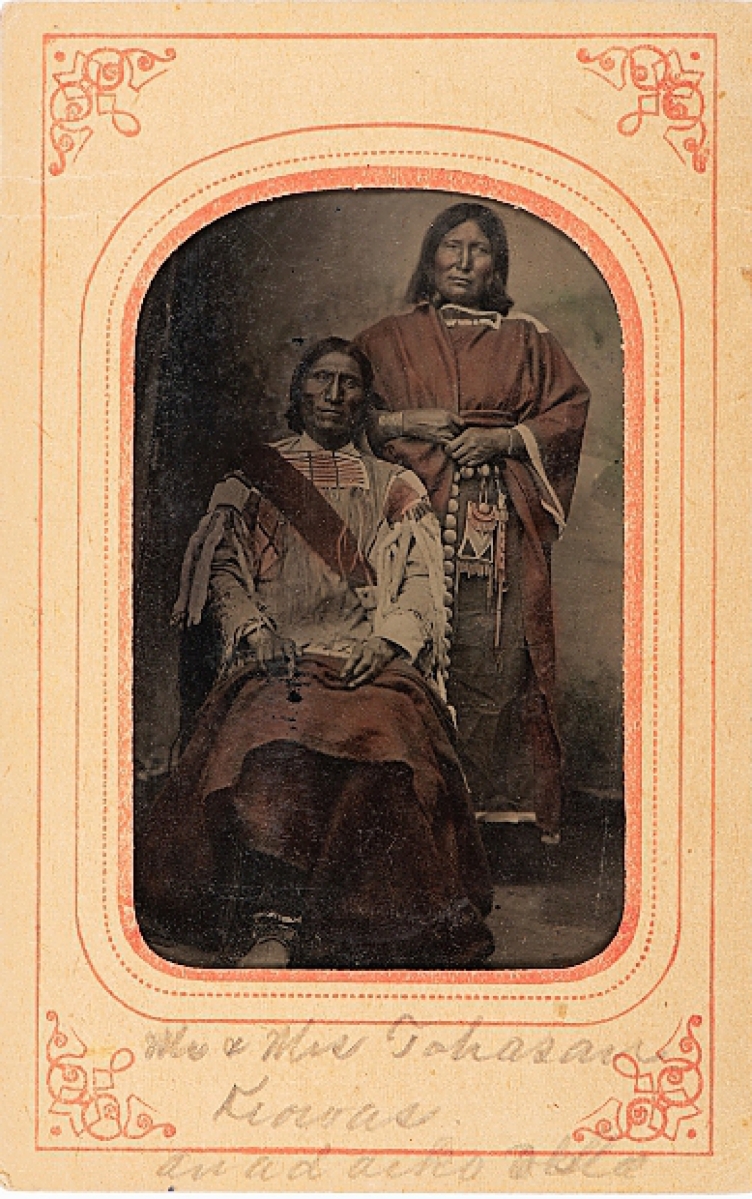

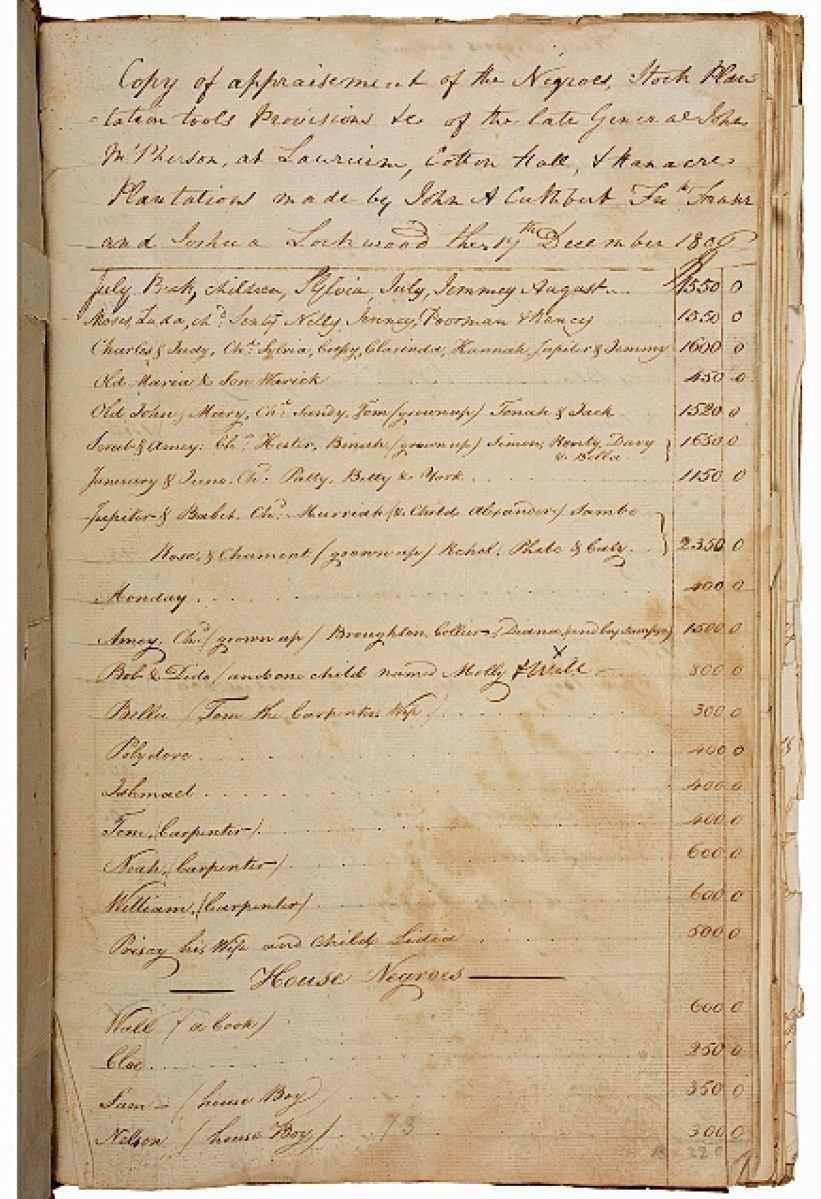

Among the section’s ephemera was an 1859 illustrated reward broadside for an enslaved runaway from Easton, Mo., $5,625; a New Orleans broadside advertising the sale of slaves, $3,125; and a detailed copy appraisal of the estate of Revolutionary War General John McPherson from 1808, which included content regarding the slaves he possessed across a number of plantations, which quadrupled estimate to bring $4,375.

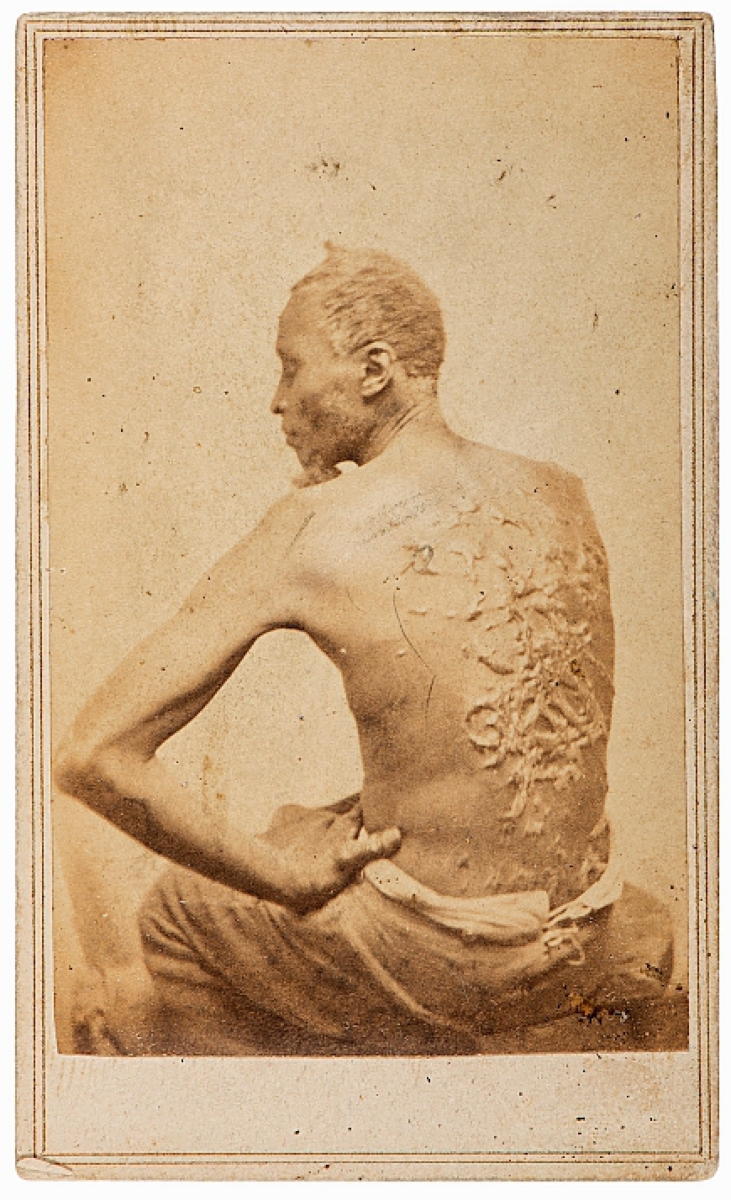

African Americana in photographs found solid results in a CDV of “Gordon,” an escaped slave who shows his heavily scarred back to the camera. It sold for $4,688. Gordon made it across Union lines in 1863, where Northern abolitionists had this picture taken to popularize the horrors of slavery. It was later published in Harper’s Weekly. A CDV of Wilson Chinn depicts the branded slave from Louisiana in shackles and other restraints, taken by Myron H. Kimball: New York, NY, 1863. Net proceeds from the sale of the CDV at the time were devoted to the “education of color people in the Department of the Gulf, now under the command of Major-General-Banks.” That image tripled estimate to bring $3,625.

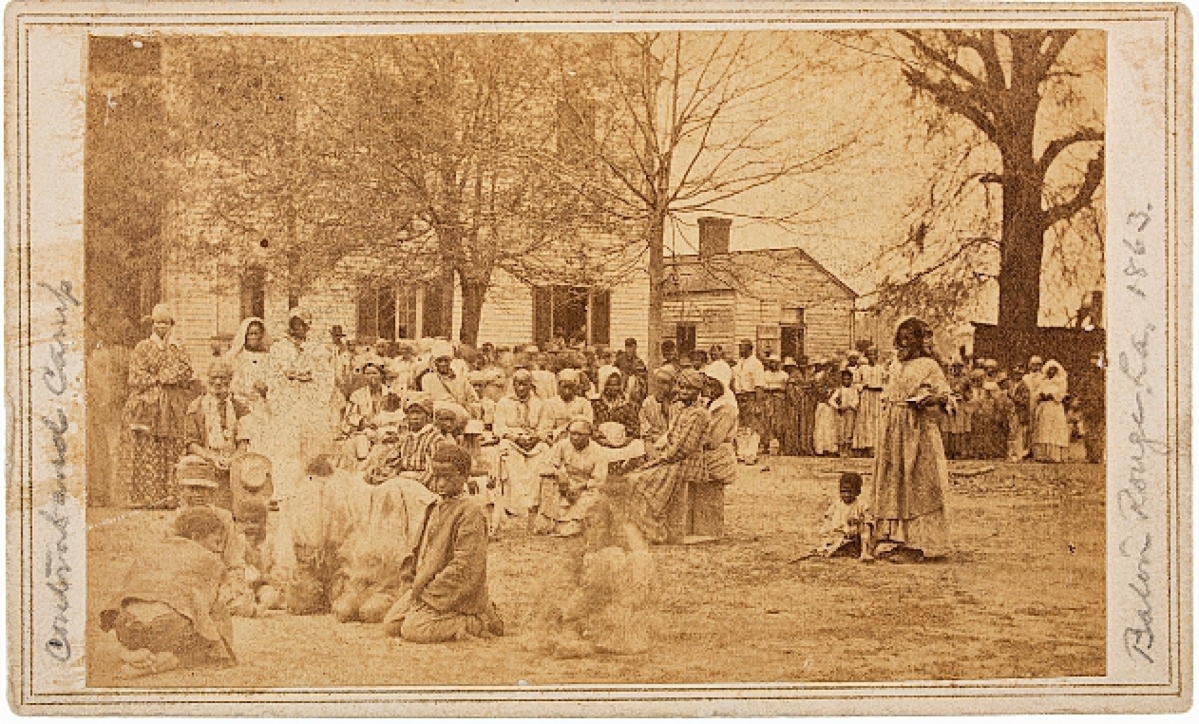

Two CDVs of Sojourner Truth sold right next to each other, both doubling the $1,500 high estimate to bring $3,125 and $3,000. Rising to five-times estimate at $5,625 was a CDV of Contraband Camp at Baton Rouge, La., dated 1863, which showed a large group of formerly enslaved people of all ages gathering outdoors. Cowan’s said the building behind them was once a female seminary, which was repurposed during the Civil War as government housing where emancipated enslaved people lived and received schooling on a minimal level.

A crib quilt with a hidden message brought considerable interest as it sold for $5,000 above a $2,000 high estimate. The quilt, decorated in a stars and stripe pattern, featured the words “Abe Lincoln will save us now” stitched in white thread on a section of white stripe, thought to have been done in this manner so as to conceal the message. It was signed “ML” and dated 1863, the same year the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, which would give real hope to all African Americans in the United States. Horstman said the quilt produced some of the most attention in the sale.

Horstman said that she finds the identified soldier pictures most compelling. By looking at when a photograph was taken – before, after or during the war – and identifying a soldier and placing them within a unit, a story begins to unravel where a significant period of their life experience can be pieced together.

The “Beardstown Portrait” of Abraham Lincoln, taken by 18-year-old Abraham Byers in Beardstown, Ill., was likely reproduced a number of times, but this period tintype is the only copy known. The original ambrotype resides with the University of Nebraska. Cowan said that in his entire career, he has never seen another. The portrait is famous for its depiction of a beardless Lincoln as a lawyer in a white linen suit, fresh off the win of the “Almanac Trial,” where he got his client acquitted of murder charges by producing an almanac as evidence showing the night of the murder was a moonless night. A single witness said that he saw the murder unfold from 150 yards away, with Lincoln arguing that it was not possible to see anything from 150 yards away on a pitch black night without the light of the moon. The portrait sold for $18,750.

“The hard images in particular, those are one-of-a-kind, so you’re not going to find another one,” she said. “Whenever they’re identified, that’s special. In the case of Private Conrad Miller, you just look at it – it’s just a young man going to war, and then he experiences the terrors of fighting, and then he gets imprisoned at Andersonville Prison Camp, which is notorious. Just by the ID, it’s always fascinating to find out what they went through.”

Of that ninth plate ambrotype, which sold for $2,250, the catalog said, “Conrad Miller mustered into Company C of the 5th West Virginia Cavalry Regiment (originally organized as the 2nd Infantry Regiment) in January of 1864. He was imprisoned at Andersonville Prison Camp (date unknown) and died there in August of 1864. Disease was a leading cause of death of the nearly 13,000 men who perished at Andersonville, and diarrhea was a commonly experienced symptom among the sick. Miller is buried at Andersonville National Cemetery, Gravesite #6960.”

In the case of a tintype of an African American, Horstman said, “He’s wearing a GAR badge. He’s just sitting back and relaxing, and you think ‘wow, what did he go through?’ He probably went through quite a bit.” That was presented in a suite of eight photographs that all together brought $352. Accompanied with them was an elementary school picture with three rows of children, credited on the mount verso to A.E. Alden: Boston, Massachusetts. One lone African American girl stands in the front row of an all-white class, identified by inscription on the back as the daughter of “John Brown – Grand Army Man – only colored family in Lex[ington], Lived on Forest St.” As they all came together, Cowan’s said that the tintype of the man in the GAR badge may have been John Henry Brown (ca 1840-?), a Maryland native who served with Co. G, 30th USCT Infantry, from September 1864 until December 1865. After the war, he worked as a laborer in Lexington, Mass.

Each lot in the sale is cataloged in the context of American history as far as the thread can be accurately pulled. Horstman said that her team, including cataloger Emily Payne and others, begin work about five months before a sale and really hit production mode three months out. “That’s what it takes to draw the attention and do the research, we want bidders to realize how important these things are,” she said.

Cowan, who started the department himself and who holds a PhD in anthropology, says he’ll cherry pick the sale and do the research he is interested in, but the catalog is largely in the hands of Horstman, Payne and others.

“All credit is due our American History team,” he said. “Consignors recognize that our commitment to presenting their property in a thoughtful and scholarly manner is something we’ve always been known for. This dedication starts and ends with our terrific staff. Kudos to them for bringing another terrific group of material together.”

Cowan’s next American Historical Ephemera and Photography auction will be held in November. For more information, www.cowans.com or 513-871-1670.