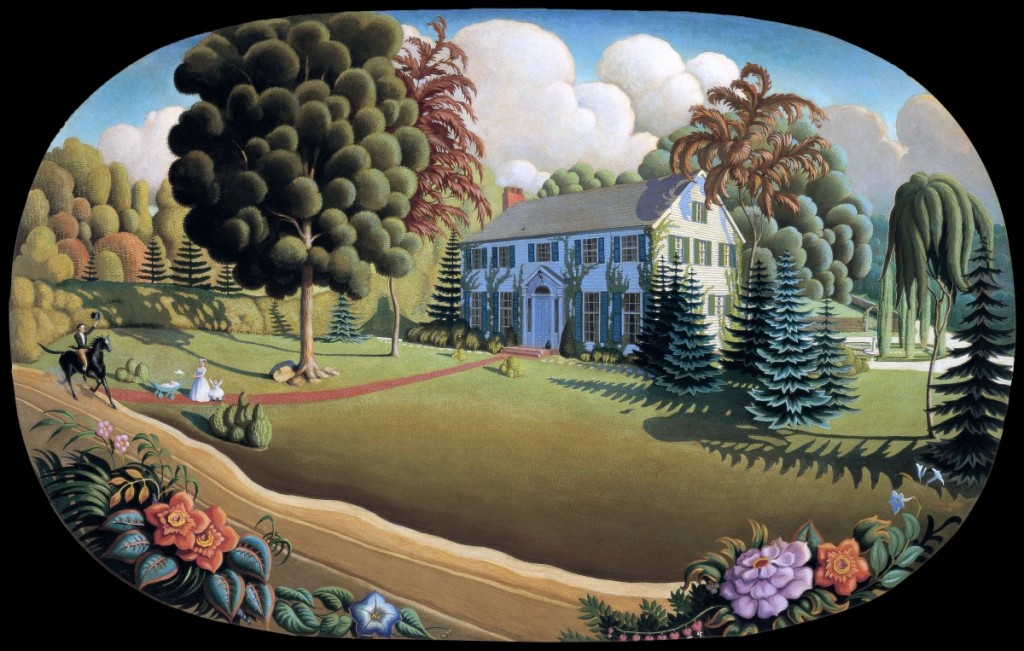

Overmantel decoration, 1930. Oil on composition board, 41 by 64 inches. Cedar Rapids Museum of Art. ©Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, New York. All designs are by Grant Wood, unless otherwise noted.

By Laura Beach

NEW YORK CITY – Perhaps it is the current popularity of contemporary realist painting that makes “Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables,” at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art through June 10, seem so of the moment. We thought we knew this son of the Midwest through such paintings as “American Gothic,” the stolid portrait of the pitchfork wielding farmer and his dour wife. But as recounted by Jessica Skwire Routhier in this week’s cover story, the more we look at Wood (1891-1942), the less we truly understand him. Ambiguity is part of the attraction. Wood remains mysterious, his oddly arresting pictures a curious blend of sincerity and satire.

While the Whitney’s insightful exhibition and catalog resist definitive conclusions about Wood, they add much to our knowledge of the artist, who, as it turns out, was a designer, craftsman and collector much steeped in the intertwined Colonial Revival and Arts and Crafts movements. Once we know of Wood’s interest in Americana, it is impossible to not see references to it in paintings such as “Daughters of Revolution,” “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” and “Parson Weems’ Fable.” The latter even appropriates the iconography of Charles Willson Peale’s (1741-1827) famous painting “The Artist in His Museum” to poke fun at the sanctimony of the George Washington and cherry tree story.

As for the Arts and Crafts movement, many will be surprised to see silver Wood produced while working at the Kalo workshop in Chicago and, subsequently, after partnering with Kristoffer Haga to form the Volund Crafts Shop. Wood’s design contributions are delightful, so much so that exhibition curator Barbara Haskell predicts his 1925 corn cob chandelier for the Iowa Corn Room at the Hotel Montrose will be an audience favorite at the Whitney.

We are indebted to Glenn Adamson for bringing Wood’s contributions to the minor arts, as they were called, to our attention and for interpreting the miscellany of Wood-made silver, lighting, jewelry, metalwork and architectural elements, murals among them, in his catalog essay “Willow, Weep for Me.” Adamson begins his essay by examining an overmantel, illustrated here, that Wood created in 1930 as part of a decorative scheme for the home of Mr and Mrs Herbert Stamats of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Citing Wood scholar Wanda Corn, Adamson suggests Currier & Ives prints as one possible source for the composition, which pictures a center-hall colonial house whose green and white palette seems more 1920 than 1800. Blowsy vegetation reminiscent of that found on early Twentieth Century hooked rugs surrounds the house. In all, the mantel telegraphs Wood’s taste for Americana, as well as a certain skepticism about the nationalist message it promoted at the time.

Adamson writes that Wood, “literate in several decorative vocabularies,” was “an avid collector of antiques” whose “work as a decorator was extremely varied.” Moreover, he says, “Wood created themed spaces that resembled the period rooms then becoming fashionable in American museums, such as a colonial interior completed in 1932 for the ‘better homes’ program of the Little Gallery in Cedar Rapids.”

Paradoxically, the work that counted the least in Wood’s lifetime may be of outsized importance, if only, as Adamson puts it, because “Collecting, handicraft and interior design were all arenas in which he could, as it were, be himself.” Happily, for us, Wood’s designs shed further light on the meaning of American antiques for early Twentieth Century collectors. In this, Wood now joins Marsden Hartley, Elie Nadelman, Charles Sheeler and other early Modernists who used Americana to interpret the cultural moment in which they found themselves.

Published by Yale University Press, the handsome catalog accompanying the show, Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables, is edited by Haskell and, in addition to Adamson, includes contributions from Eric Banks, Emily Braun, Shirley Reece-Hughes and Richard Meyer along with a foreword by Adam D. Weinberg.

The Whitney Museum of American Art is at 99 Gansevoort Street. For information, www.whitney.org or 212- 570-3600.