Figure of woman with bowl, 1995, micaceous clay and turquoise, figure 10-1/8 by 9-7/8 by 9 inches; bowl 3 by 4 inches. SAR Collection.

By Karla Klein Albertson

SANTA FE, N.M. – When an example of Pueblo pottery enters a museum or marketplace, the form and decoration is often discussed by art historians saturated in the philosophy of Western civilization. Or else, archaeologists approach the vessels as relics of past history, just as they would analyze ancient Greek vases or Roman bronzes.

“Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery” takes an entirely different approach for it is curated by members of the tribal communities it represents. The show opened in July at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture on unceded Tewa Indian lands in Santa Fe/O’gah’poh geh Owingeh.

The exhibition promises to have immense influence on how people understand Native American art expressed in utilitarian forms. For one thing, the illustrated catalog captures the interpretations of the Pueblo Pottery Collective, from more than 60 members of 21 tribal communities who chose and wrote about the exhibits, as well as curatorial essays. In the future, the show will travel for three years – closing in New Mexico at the end of May and proceeding next to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for a July 13, 2023-June 4, 2024 run.

More than 100 selected objects – both historic and contemporary – are on view, drawn from two major collections: the Indian Arts Research Center of the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, which includes the collection of the Indian Arts Fund (IAF), and the Vilcek Foundation in New York City.

As it happens, the opening of the show also celebrates the 100th anniversary of the creation of the center’s Pueblo pottery collection in 1922.

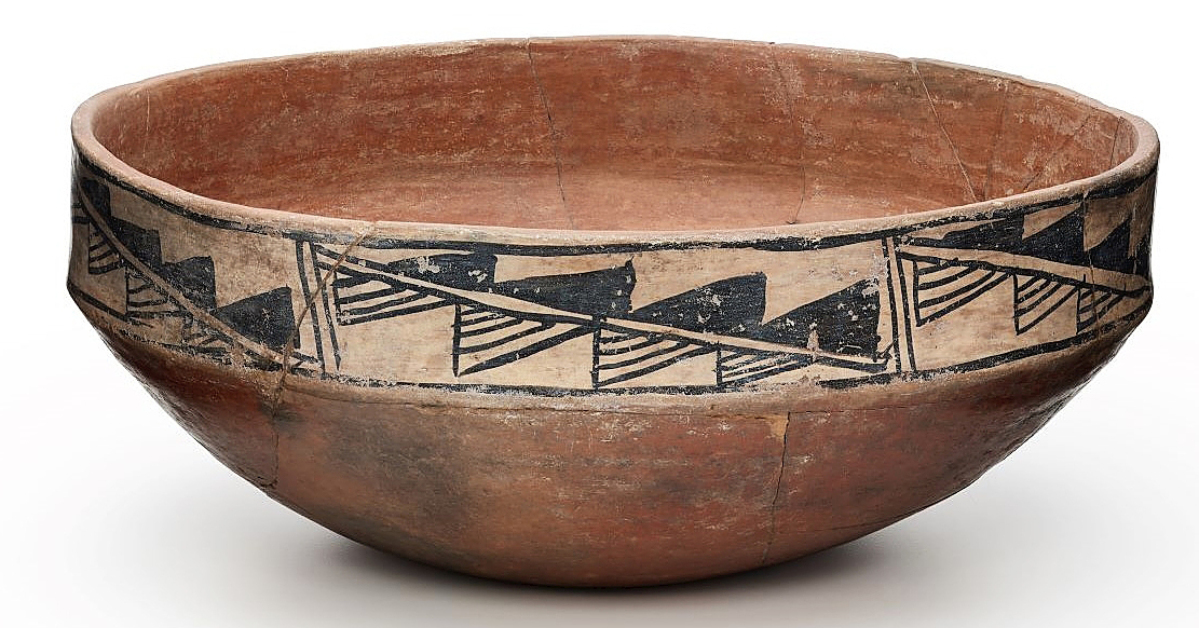

Bowl, before 1985, clay, 5-1/8 by 8¾ inches. SAR Collection.

Elysia Poon, director of Indian Arts Research Center at SAR in Santa Fe, said before the show opened: “Pottery permeates the lives of Pueblo peoples. For many, it is impossible to divorce the pieces from the people.”

In her preface to the catalog, she outlined the process: “‘For Grounded in Clay,’ each curator was given the option of selecting either one or two works for the exhibition and catalog, and then was asked to write about their chosen piece(s). General prompts were offered to assist with the writing process if required, but curators were given leeway to write whatever they wanted about the pieces, in whichever format they wished. Staff offered editing, oral-history recording and transcription assistance on request, but the content produced was entirely each curator’s own. Each community participant was compensated for their work.”

“While most exhibits of Pueblo pottery focus on historical timelines and Western-derived concepts of fine art, this project focused on the lesser-known and intangible aspects of pottery that are so intrinsic to the art and enduring cultures of Pueblo people.”

In an interview with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Poon talked about how the project began: “Although we could have done a traditional show, we wanted to work on an exhibit that would be in line with the policy work that we’ve been doing with the communities over the last decade. In 2019, we began outreach to people who had contact with Indian Arts Research Center in the past.”

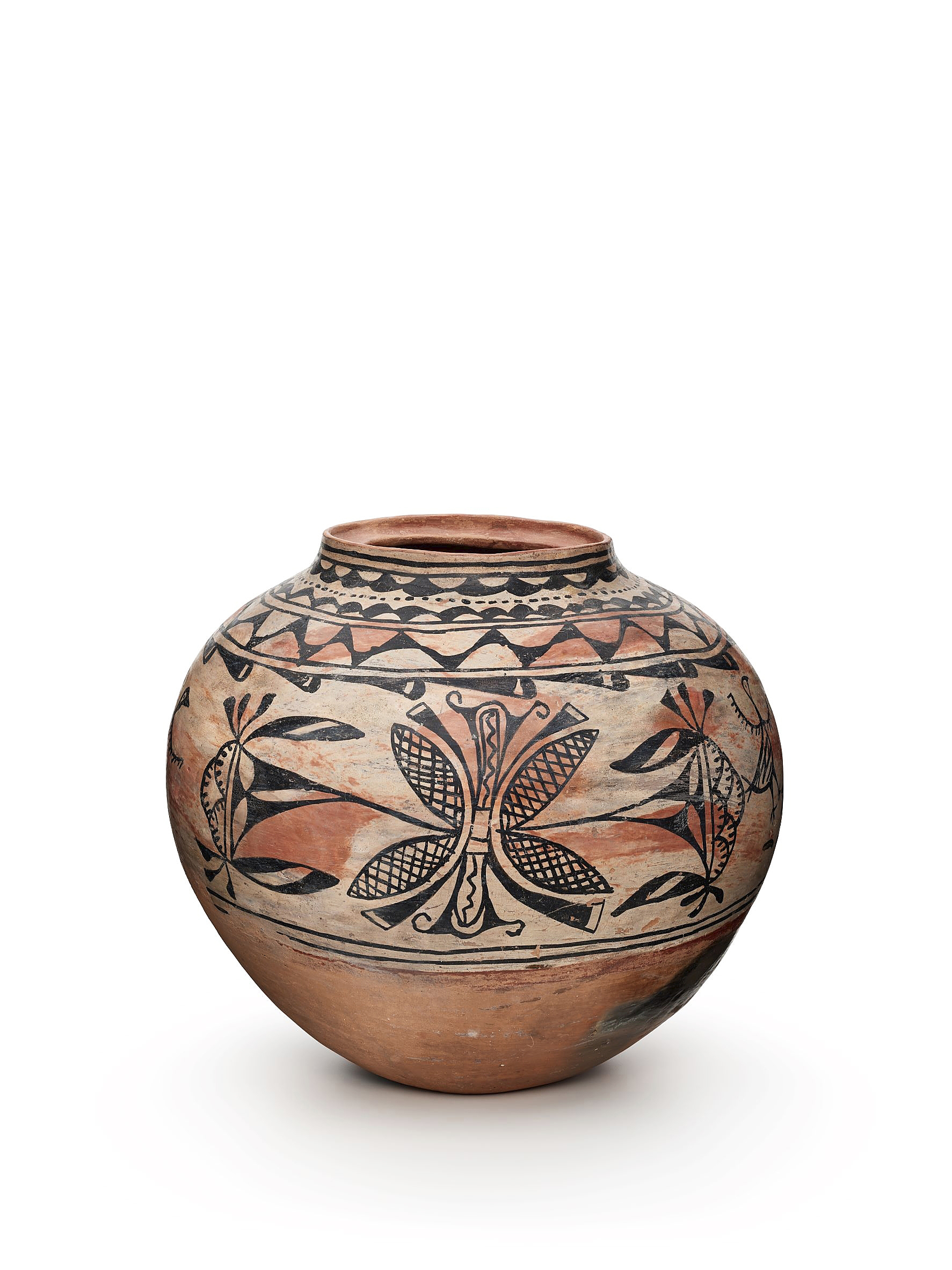

Powhogeh storage jar, circa 1820, clay and paint, 16 by 16 inches. Vilcek Foundation.

“Over many months, they came through, choosing the pieces they wanted. That was the first step.” She added that some curators chose in seconds, others looked at the pottery many times before making a choice.

One challenge intervened: “It was actually a pandemic project, whether we wanted it to be or not. The pandemic really threw us for a loop. We had all these plans for in-person meetings and community gatherings at the different pueblos – and of course, none of that happened. Nevertheless, we were very thrilled with how it turned out. It was amazing to see something so beautiful come out of a period that was so dark.”

“The exhibit was really focused on everyone’s individual writings. It was developed a little bit backwards – most exhibits will usually start out with a specific theme. But this exhibit, because we wanted to give the curators as much latitude as we could, they chose their pieces first, they wrote whatever they wanted, in whatever format they wanted.”

When asked what she hopes visitors will take away from the galleries, the director stressed, “A lot of exhibitions you see on Pueblo pottery tend to be based on art historical approaches to the technical aspects or a specific timeline. This one gets at the heart of Pueblo pottery – why it is important? And how was it involved in people’s lives? We want people to see the pottery not as static objects but creations that had lives in themselves. They had their own history and interacted with individuals and the world around them.”

As mentioned, the curators were allowed great latitude in their approach to a chosen vessel. Some considered how and why the pottery was made. One wrote: “The master potter had the skill not only to form a jar this size, but to carefully execute other steps in its creation, including a successful outdoor firing. The designs on both the neck and body are classic Acoma pottery patterns depicting clouds, rain and corn fields. This jar sings loudly to me through its design and its lived experience at Acoma.”

Mesa Verde ladle, circa 1050-1300, clay and paint, 2 by 11-7/8 by 5 inches. IAF Collection at SAR.

Others evoke memories of more recent ancestors: “I see the flared collar and high neck in this jar. I see my grandma in the beauty from the earth.” Another writer, choosing a pottery Nativity group, wrote about the infusion of Catholicism into a Pueblo society that already practiced a Native religion and how a relative managed to participate in both. Other vessels stirred curators to expressions of poetry or cosmic questions.

Poon said in conclusion: “Of course, the pottery has many styles. And I think another surprise was how everyone chose the pieces. What the group ended up choosing was what was beautiful to them – examples that reminded them of past memories and spoke to them on a deep level. When we put the pottery together for the first time after the pieces had been chosen, there were many pieces that had cracks and signs of wear and patina. And this spoke to how well-loved this pottery had been, instead of just aesthetically beautiful.”

To see more examples from the exhibition, see bios of the curators, and watch video from the show, go to the dedicated website: www.groundedinclay.org.

The Museum of Indian Arts & Culture is at 710 Camino Lejo. For additional information, 505-476-1269.