Curators described this painting on the wall placard, “Tompkins Harrison Matteson summarizes in one scene a number of dramatic incidents that occurred during the days of George Jacobs Sr’s examination and trial. Most of the action focuses on the dramatic moment when his own granddaughter, Margaret, testified against him. Placed in the center of the painting, she kneels and points her finger directly at her grandfather, who responds by pleading his innocence with upraised arms. The other dominant figure, the woman lunging forward, may represent Margaret’s mother, Rebecca, who was also arrested. The judge standing before Margaret holds a letter in one hand while pointing with the other to documents on the clerk’s table. This gesture might reference the letter Margaret gave the court recanting her earlier testimony, which came too late to save her grandfather from the gallows.” “Trial of George Jacobs, Sr. for Witchcraft” by Tompkins Harrison Matteson (New York, 1813-1884), 1855. Oil on canvas. Gift of R.W. Ropes, 1859.

By Jim Balestrieri

SALEM, MASS. — Witch trials and witch hunts, inquisitions and accusations of heresy and spiritual impurity all resolve into one image, one small, terrible, universal gesture: the pointed finger. Thrust out in condemnation, sneering, “You! Not me. Never me. You,” the pointed finger divides, opens an ideological chasm, conflates the personal with the moral and political and narrows it all down to the tip of a crooked forefinger.

Salem, Massachusetts. 1692-93. The witch trials. They hardly need introduction or summary. Say “Salem,” say “witch trials,” and you have stepped into the American consciousness. Those events, occurring more than three centuries ago, exert enormous power on our subsequent history. They are part and parcel of our lore, our mythology, our popular culture, evoked as a cautionary tale whenever hysteria, rumor, bad science and revenge combine to create a cold cocktail of false justice, absent empathy and vanished mercy. Pointed fingers beget pointed fingers. 2020, anyone?

Full disclosure: I live in Sleepy Hollow Country. Home of the Headless Horseman, Ichabod Crane, Rip Van Winkle. As Washington Irving wrote in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, “The whole neighborhood abounds with local tales, haunted spots and twilight superstitions… and the nightmare, with her whole nine fold, seems to make it the favorite scene of her gambols.” Irving’s tales have given rise to a culture where Halloween is our Christmas, where cemetery walks, blazes of jack-o-lanterns, a wild costume parade through the streets and Trick or Treating occur on a scale that warms the heart of any pediatric dentist, dominating the whole of October and spilling over into September and November. We always imagine a rivalry with Salem for Halloween capital of the world. But the origins of our traditions lie in Irving’s fictions, in ghost stories told ‘round the hearth, while Salem’s lie in terrible truths. For sheer fun, we might have Salem beat; but for a story rooted in actual fear with actual victims that resonates with a palpable feeling of a ghostly, unspeakable past we can’t — and shouldn’t — turn into a carnival of souls — no contest. Salem wins, and, in my estimation, particularly after rereading some of the accounts and original testimonial documents and objects owned by both the accused and their accusers, as they are presented in the new exhibition, “The Salem Witch Trials, 1692,” at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem.

Turned great chair owned by Philip and Mary English, circa 1674, attributed to Samuel Beadle Jr (U.K./Salem, Mass.,1643-1706). Oak and pine. Gift of Mary R. Crowninshield, 1908.

Look at that chair. Here’s the label: “Attributed to Samuel Beadle, Jr. 1643, Isle of Jersey, United Kingdom — 1706, Salem, Massachusetts. Turned great chair owned by Philip and Mary English, about 1674. Oak and Pine. Gift of Mary Crowninshield, 1908.” Innocent enough. But whoever took that picture nailed it. Severity. Austerity. As the ghost of a Witch Trial judge were still sitting there, examining one of the accused. “Did you curse your accuser and make her ill…? Did you cause winged demons to be created and fly around the room…? Did you fly…?”

But that isn’t the story at all. The real story is worse, another order of reproach altogether.

In 1692, Philip English was one of the richest men in Salem, a merchant as opposed to the predominantly agrarian Puritans. He was an Anglican from the Isle of Jersey whose real name was French — Phillipe d’Anglois. His actual background was Huguenot. He was not, therefore, a Puritan. He had avoided his taxes, it was later said, and, as tax collector, let the taxes of his cronies slide, it was said. He was a tough businessman (this part appears to be well-documented). In April 1692, English’s wife, Mary, was accused of witchcraft and arrested. In May, she was sent to a Boston jail to await trail. Meanwhile, Philip was accused in church, charged by Susannah Sheldon with pinching her and demanding that she sign the Devil’s book or have her throat cut. People claimed to have seen ghosts of men English had murdered. Then William Beale, who had lost a vicious boundary dispute with English, said that English had given him a nosebleed and that the sudden deaths of two of his sons during the dispute has stemmed from Philip’s dark arts.

English got wind of his impending arrest. And this is where the chair comes in, with torture of a different kind, the torture of man sitting in it, fearful for his wife and for himself, wondering what to do and how to do it. After joining his wife in jail, the couple were aided in their flight — by hiding under some laundry, by one account — and waited out the madness in New York. On their return to Salem, they found that the infamous witch hunter Sheriff Corwin had confiscated much of their property. English made another go of it, sued and received some of what he’d lost, and — it is said — stole Corwin’s body after the Sheriff’s demise. Salem managed to re-baptize English in rumor, re-demonizing him long after the witch trials had been deemed shameless and murderous.

The carved initials and date in the central medallion celebrate the 1679 wedding of Joseph and Bathsheba Pope, the latter who would stand as an accuser in the witch trials. Valuables cabinet owned by Joseph and Bathsheba Pope, 1679. Made by James Symonds (Salem, Mass., 1633-1714). Oak, maple, iron and paint. Museum purchase, made possible by anonymous donors, 2000.

Back in 1908, Mary Crowninshield probably heard some spectral wailing reverberating from that chair and walked it right out of her home and straight to the museum.

Was Philip English a good man? A hero out of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible? Probably not. What law, civil or ecclesiastical, says you have to be spotless to be wronged? And by what alchemy of envy, what sickness of mind, was he transformed into a sorcerer whose wealth could be attributed to witchcraft in open court? Salem’s legacy points its forefinger at the pogrom, at the Elder Protocols of Zion, at the countless Islamophobic tracts that pollute the Internet, at race, ethnicity, gender and class whenever and wherever they are painted with a broad brush of scapegoated suspicion, sentenced and condemned, buried under masses of alternative facts and ludicrous levels of detail describing just how diabolical “they” are and always have been.

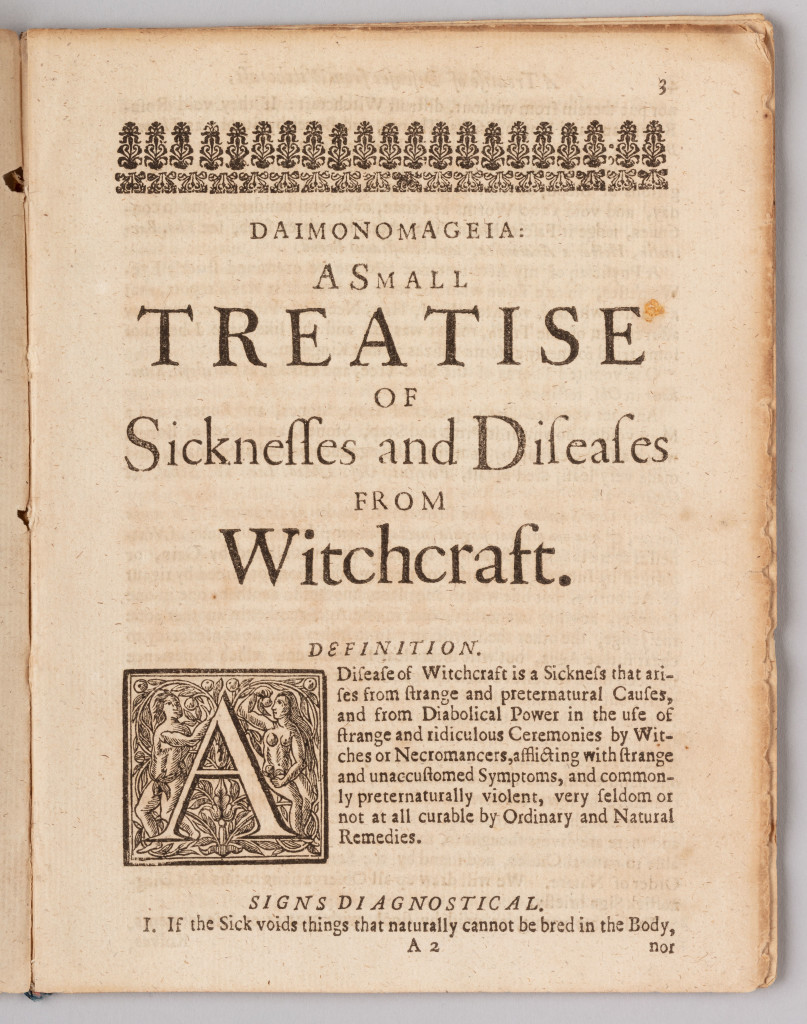

Detail. Go online and blow up the documents reproduced in this story. Or dip into digital pages from some the manuals of demonology that the cruel examinations of witches and demons relied on. What should be instantly amazing is the exacting, nauseating level of detail the experts go into: what witches look like, how they conceal themselves; how they insinuate themselves into the minds of the innocent and pure or pretend to, just for the fun of it; how they transform; how a slight or a glance can be a sure sign of possession. Incubi. Succubi. Hosts of demons in innumerable species and subspecies. O, they have their ways. They. Fascinating hogwash, but hogwash nonetheless.

Or consider the testimony of Tituba, the enslaved woman from the Caribbean whose voodoo beliefs played right into the hands of the witch hunters. For her, spirits — good and evil — were as real as Jesus. After telling stories of her native land to young Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams, who sought to learn their future fortunes, what choice did she have but to help them in her own way? What chance did she have then, after the girls became “mysteriously” ill? Almost certainly beaten by her owner Samuel Parris into pointing the finger elsewhere, away from the Parris family, Tituba lingered in jail, was later sold, and disappears into history.

Daimonomageia: A Small Treatise of Sicknesses and Diseases from Witchcraft, and Supernatural Causes by William Drage (English, 1637-1669), published 1665. Phillips Library. Drage was a physician and apothecary who compiled medical books into the English language.

In the mid-Nineteenth Century, the neo-Gothic novels and stories that had arisen in Europe attached themselves to Salem in America, especially in the fictions of Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose great-grandfather had been one of the judges in Salem. The House of the Seven Gables and The Scarlet Letter have their roots in hysteria and the finger of accusation and in the dark, romantic New England setting with its layers of dark history. From H.P. Lovecraft to Shirley Jackson to Stephen King, Salem’s lot has been the sounding board for the madness of the crowd that takes hold, periodically, in America.

Two paintings in the exhibition, done in the 1840s — just when Hawthorne was turning his attentions to Salem — by Tompkins Harrison Matteson (1813-1884) — capture the frenzy of witches “revealed” through examination. But for all their tumult, notice the fingers, fingers everywhere, all pointed at someone else.

Some years ago, on a whim, I bought a book titled Demoniality by Friar Ludovico Maria Sinistrari (great last name). Written in the 1600s, my book was translated into English by the Reverend Montague Summers and issued in a very limited edition. Incubi. Succubi. A preoccupation with sex. I gathered all that without ever cutting the pages. It might have been fun in a sort of B-horror film way, like reading the fictional Necronomicon that Lovecraft always refers to, but in truth, it reads like the trial of the witch in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Yet, people lost their lives because of what’s written here. If I cut the rest of the pages I would feel as though I were breaking a hogshead of bile and letting it spill out onto the world.

I’ll stick to my Headless Horseman. After all, he’s only Brom Bones holding a jack-o-lantern, right? If I want his spirit to begone, I simply close the book. The book on the Salem Witch Trials doesn’t close so easily. On stones at the Salem Witch Trials Memorial are inscribed the names of those who were tried, tortured and died in 1692. The memorial was dedicated by Elie Wiesel in 1992. The afterimage of that chair, imagining Philip English sitting in it —cold sweat, white knuckling those unyielding oak arms, torturing himself — glows hovering behind my eyes.

Haunting History: ‘The Salem Witch Trials, 1692’ is on view through April 21, 2020 at The Peabody Essex Museum, East India Square, 162 Essex Street, Salem, MA. For more information, 866-745-1876 or www.pem.org.