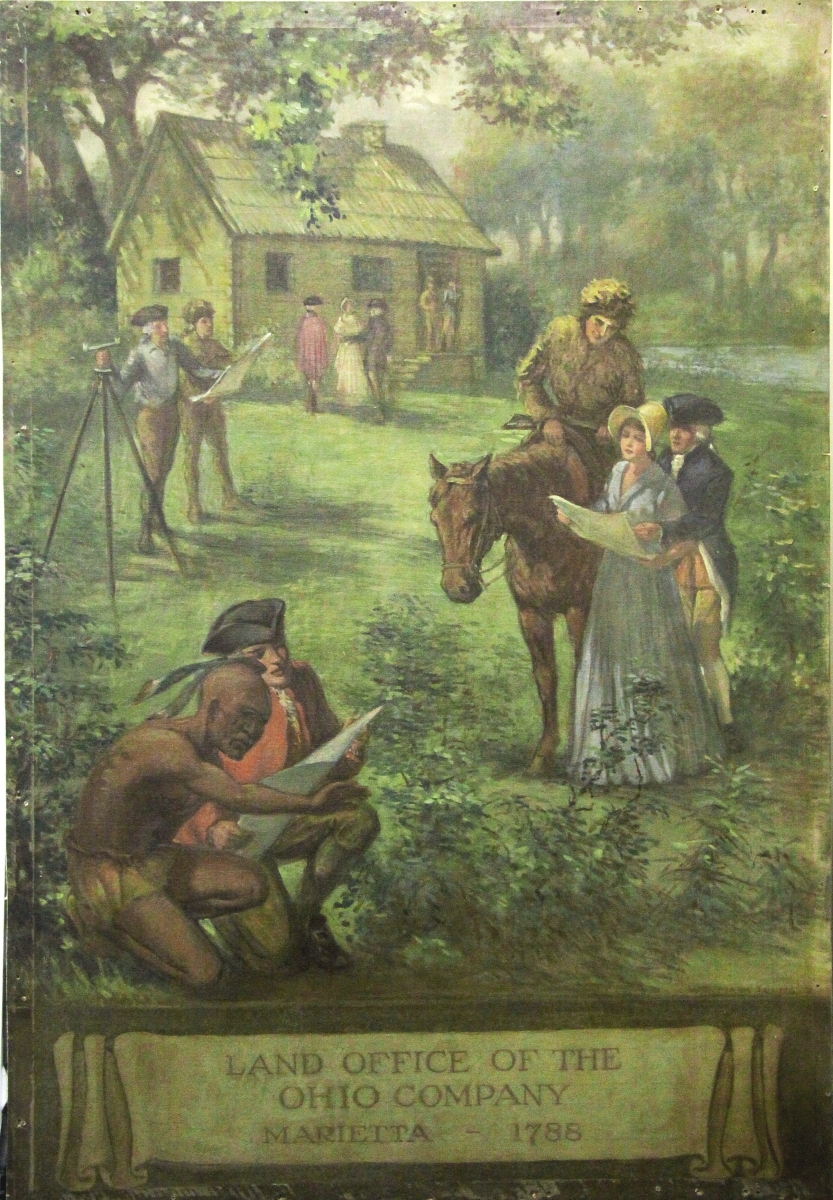

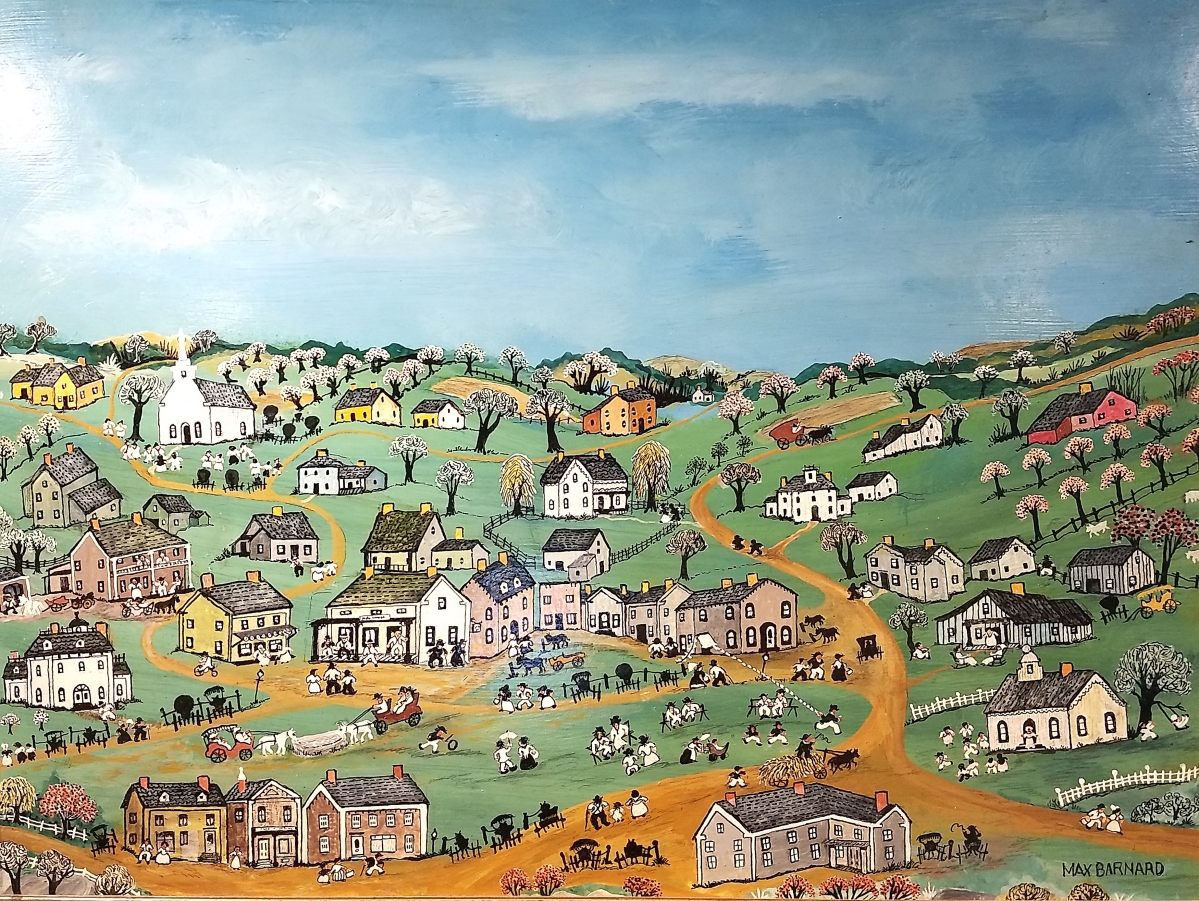

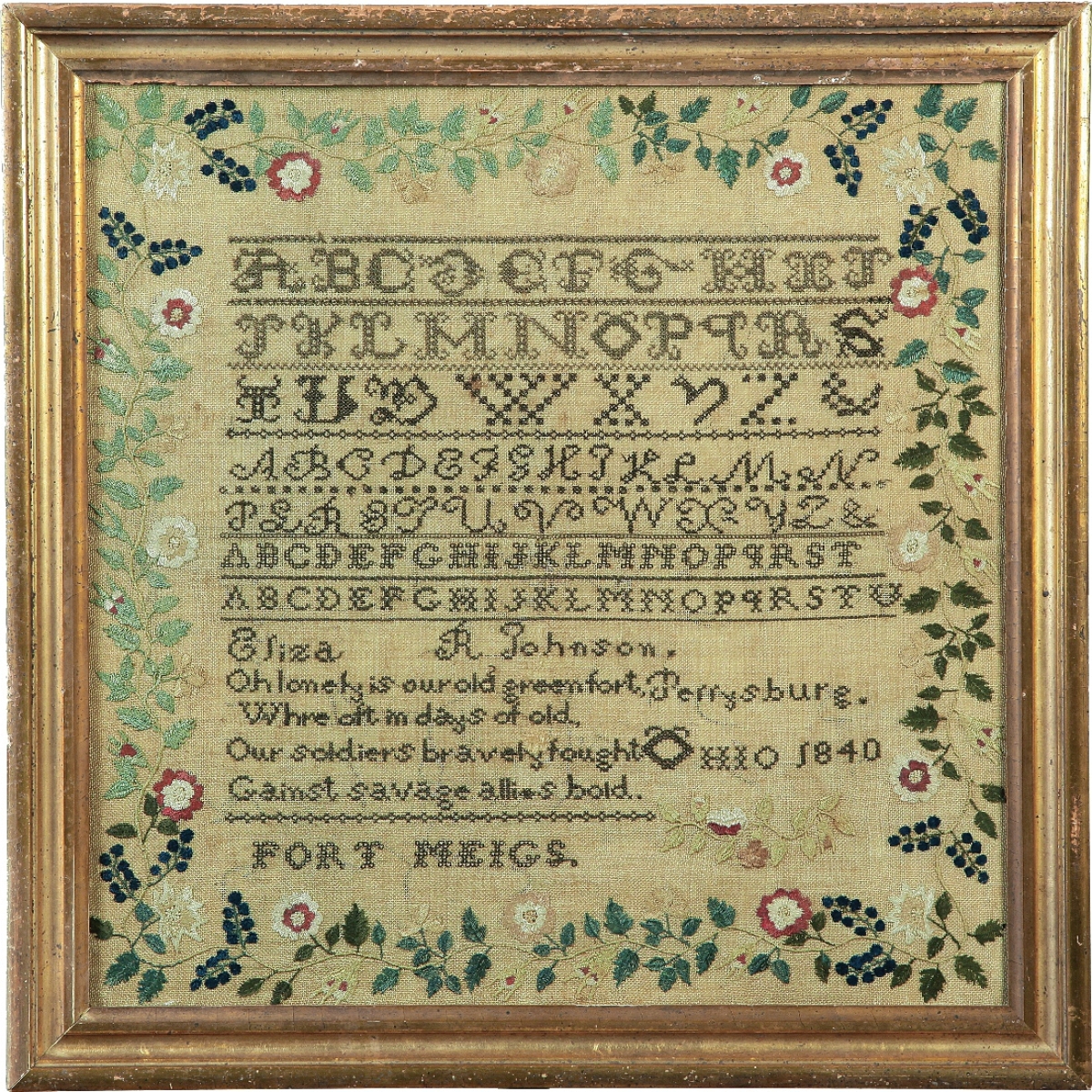

Max Barnard (Ohio, 1884-1978), “Cherry Valley,” circa 1960, oil house paint on Masonite. Chagrin Falls Historical Society.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

LANCASTER, OHIO – A new exhibition at the Decorative Arts Center of Ohio (DACO) investigates the role memory and nostalgia played in a body of work created during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries by a group of Ohio folk artists known collectively as “memory painters.”

“Hindsight: The Art of Looking Back” was curated by Andrew Richmond, president and chief executive officer of Wipiak Consulting & Appraisals, and his wife, Hollie Davis, president and chief executive officer of Prices4Antiques.com. The title is a riff on the saying “Hindsight is 20/20,” but apropos of a moment when Covid-19 has created poignant opportunities for memory and nostalgia.

Paintings by regional artists Sala Bosworth (1805-1890), Paul W. Patton (1921-1999), Harold Everett Bayer (1900-1996), Charles Owens (1922-1997) and Tella Kitchen (1902-1988) form the nucleus of the exhibition, but it was the work of fellow Ohio artist Leuty McGuffey Manahan (1889-1977) that provided the idea and impetus for the project.

A native of McGuffey, Ohio, and a relative of William Holmes McGuffey, who edited the Eclectic Readers that became informally known as “McGuffey Readers,” Leuty moved to Columbus to marry John Russell Manahan. In the 1950s, and with no formal training, she began to paint pictures relying on memories of her childhood; she completed about 80 works before she died.

An object and its owners. This turned maple sugar bowl is shown with a photograph of its original owners, members of the Pease family, Concord, Ohio, late Nineteenth/early Twentieth Century. Private collection.

Manahan was known and exhibited throughout Ohio, including in 1961 when the Franklin County Historical Society in Columbus, Ohio, featured 54 of her works in an exhibition titled “Early American Farm Life.”

In the foreword of that exhibition, Manahan described her artistic inspiration: “Our lives are enriched for having experienced a deep nostalgia of the past. Our contact with former generations gives us a desire for objective knowledge and an assurance that we are progressing in the fulfillment of the goal of our present day living. To understand how the early American farmer lived, the difficulties he had to surmount, the kind spirit and compassion he possessed, will enable us to meet our adversities with self-reliance and gratitude. My pictures are meant to bring an intangible worth to those persons who are able to gain from them the noble spirit of our pioneer grandfathers.”

According to the biography Richmond and Davis compiled for the exhibition, Manahan received a commendation from then Lt Gov Richard Celeste. However, she never achieved the fame that other folk artists enjoyed. When asked if she regretted not being discovered, she quipped, “Discovered? I never knew I was lost.”

Despite offers, Manahan was reluctant to sell her work during her lifetime, a reticence that may have limited her legacy. After Leuty’s death, Manahan’s daughter put her works – from sketches and studies to finished paintings – in a closet where they remained for nearly 30 years until she agreed to sell them to a private Ohio collector who had seen some of Manahan’s works in a small Ohio exhibition. That collector – who has for the time being chosen to remain anonymous – has decided the time is right to tell Leuty’s story and contacted Richmond with the idea of the show.

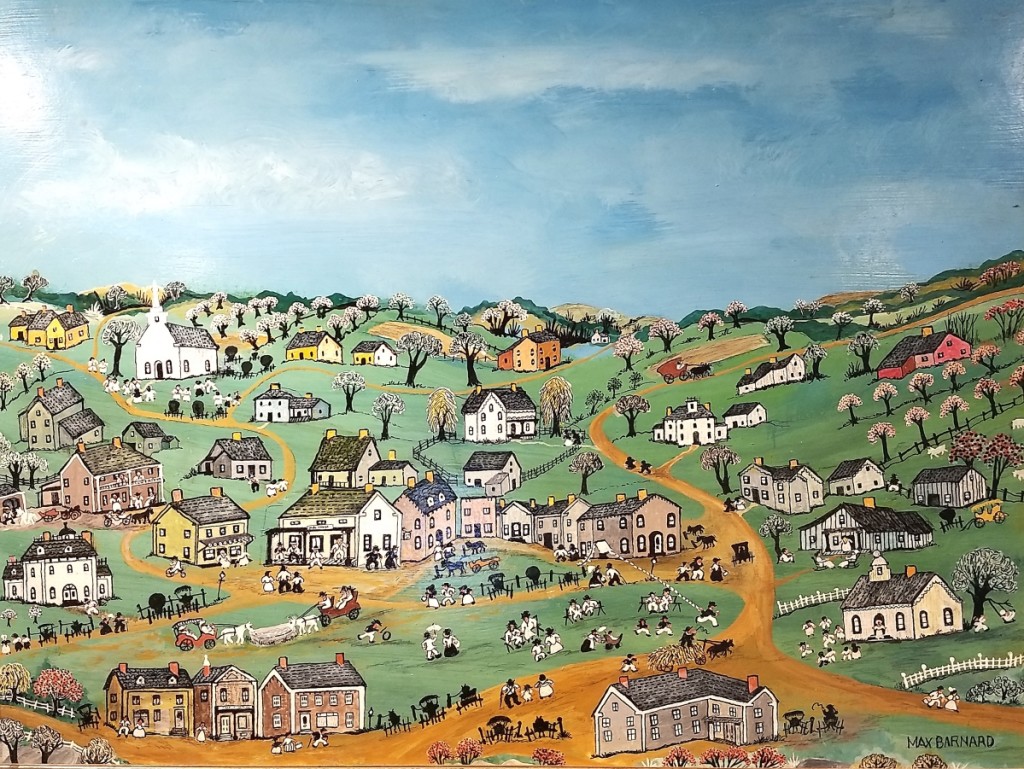

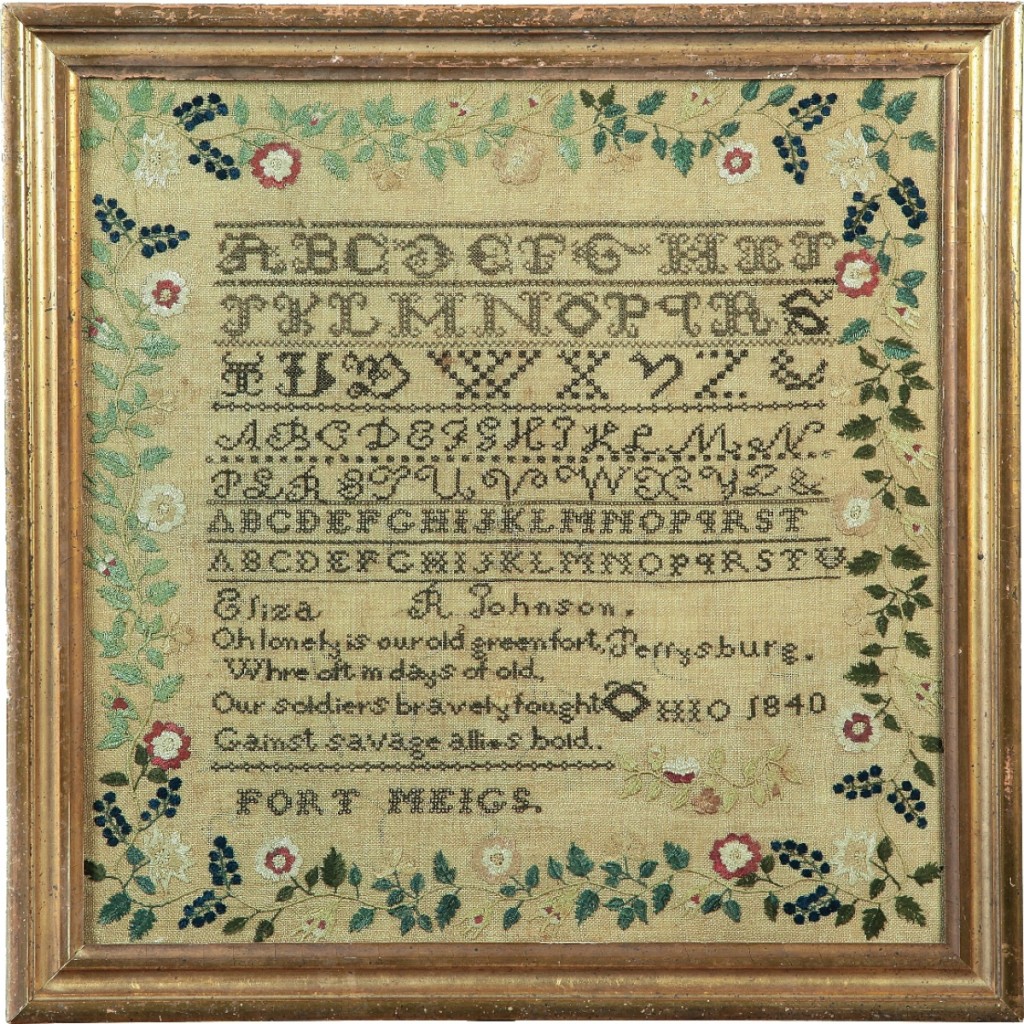

This sampler, worked in silk on linen by Eliza R. Johnson of Perrysburg, Ohio, in 1840, references local Fort Meigs in her verse: “Oh lonely is our old green fort / Where oft in days of old / Our soldiers bravely fought / Gainst savage allies bold.” Private collection.

“When I first encountered the homespun paintings of Leuty McGuffey Manahan, I was struck by the nostalgic charm of her depictions of her childhood in rural Hardin County, Ohio,” said Richmond. “These paintings were not only created from memory but were designed to act as memories made real on canvas – memory paintings, if you will.”

Manahan’s works, of which “Hindsight” features nine, can best be described as folk genre pictures: depictions of daily life, in a naïve and humorous way, and typically with an added hint of social satire. She filled her paintings with so many details that it typically takes multiple viewings to fully appreciate them all. Her style is primitive but focused, and for the keen observer, there is an edginess in both her content and her execution, and her paintings form a continuous narrative that emphasizes the importance of the role women played in rural American life.

“Manahan’s interior scenes are not only based on what is remembered but a strong sense of nostalgia,” said Richmond. “These images and objects, like memory itself, exist on the boundary between history and nostalgia, between fact and fiction. This boundary has always been a challenging place to interpret, perhaps even more so today than ever.”

The show includes “Stage Stop” by Grandma Moses, which is on loan from the Bennington Museum. It provides a useful comparison to the works of the other artists, as well as that of Manahan, who was often referred to as “Ohio’s Grandma Moses.”

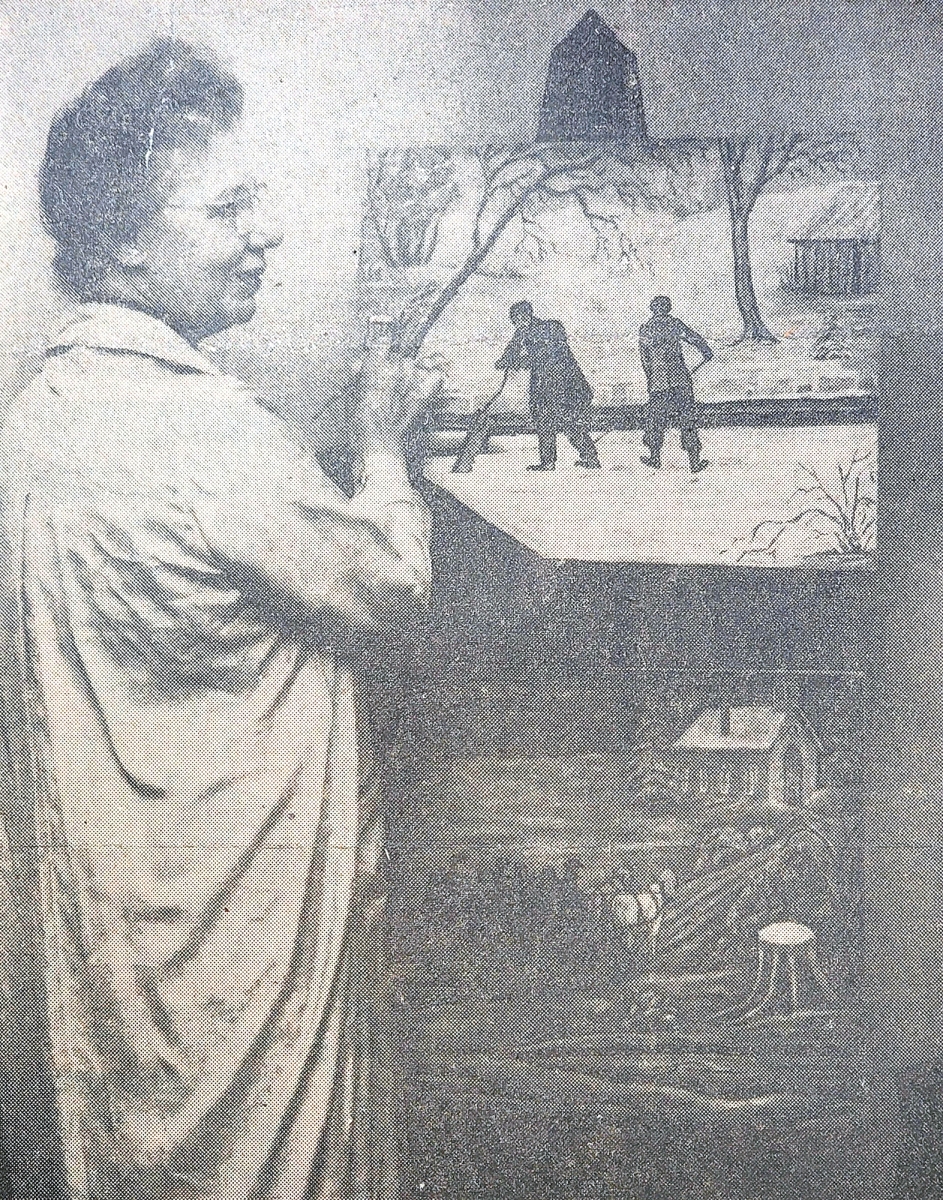

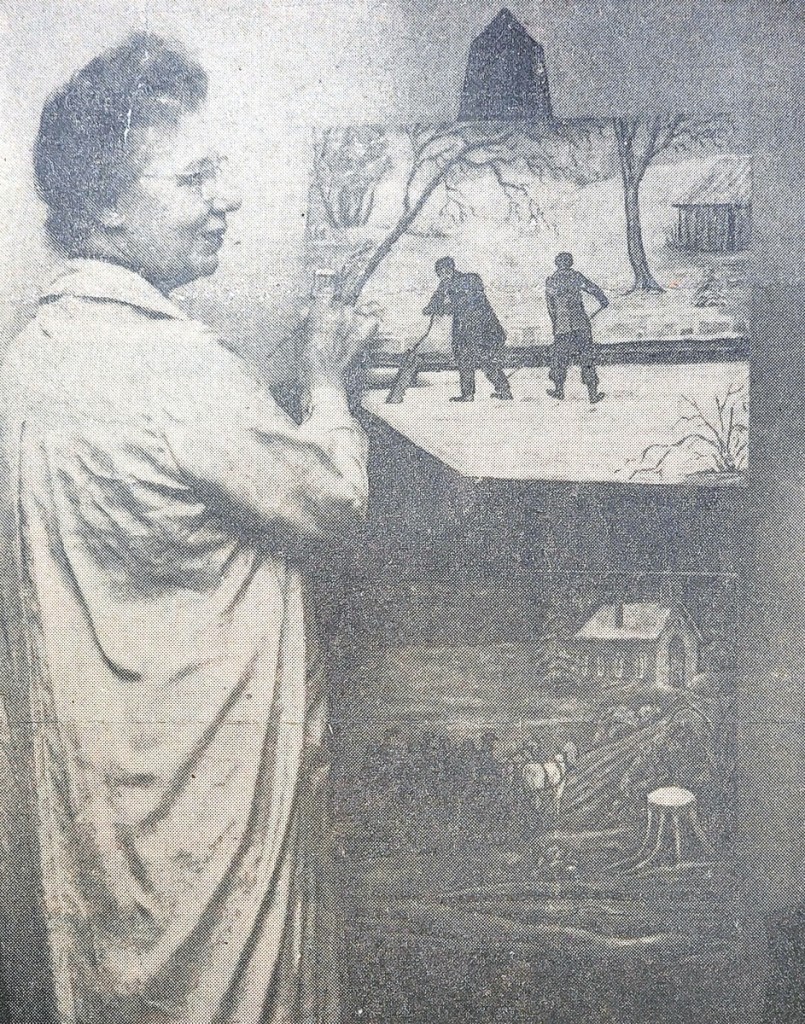

Photograph of Manahan at work painting “Cutting Ice,” which was published in the Columbus Dispatch on June 20, 1955, in an article about an exhibition she had in New York City. She has yet to add the small child, dog or figure throwing the snowball.

“Someone applied the [‘Grandma Moses of Ohio’] moniker to Leuty at some point; Paul Patton is referred to as the ‘Grandpa Moses,'” Richmond says. “I suspect the name gets bandied about quite a bit, but we wanted to get an actual ‘Grandma Moses’ because it’s the name everyone knows.”

Beyond their contemporaneous lives and shared inspiration rooted in rural memory, the two artists and their works are quite different. Robertson focused on the New England landscape, while Manahan’s works typically depict interior views, or perhaps exterior views, but in a much more intimate manner. Humor is also a critical component to Manahan’s works, a characteristic seen less frequently in Robertson’s paintings.

The exhibition poses questions meant to prompt the viewer to consider one’s earliest memories, how memories are preserved, how memories change over time or how they differ from those of other people, and who one shares memories with. No two viewers will have the same museum experience.

Rocking chairs and spinning wheels are two iconic emblems of early American history. This late Nineteenth Century example combines both. Private collection.

Props to prompt a trip down memory lane come in the form of three-dimensional pieces – referred to as “memory objects” – that provide a physical embodiment of past times. Photographs of colonial-style interiors and gardens taken by the early Twentieth Century New England minister Wallace Nutting. Colonial revival furnishings designed, if not made, by Nutting and his wife. From a rocking armchair made in the late Nineteenth Century from parts of an early Nineteenth Century spinning wheel to a memory jug that has been mounted as a lamp, these tangible objects will certainly encourage the viewer to recall similar objects from their own past or make mental comparisons with different objects in one’s personal history.

This story was written against a backdrop of the Christmas and New Year holidays, which, because of the pandemic, have looked markedly different than they once did. One wonders what the Ohio memory painters, had they lived through this time, might have remembered and how those memories would manifest.

“Hindsight: The Art of Looking Back” will be on view through April 24.

The Decorative Arts Center of Ohio is housed in the Reese-Peters House at 145 East Main Street. For additional information, www.decartsohio.org or 740-681-1423.