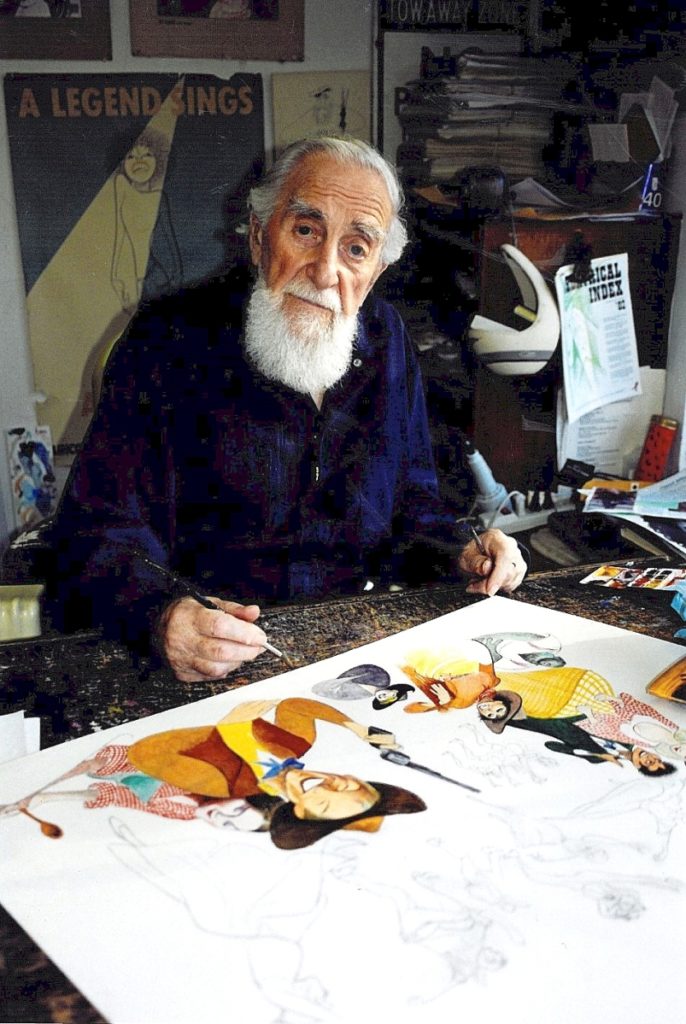

Al Hirschfeld photographed by Louise Kerz, former president of the Al Hirschfeld foundation, 2001.

By Z.G. Burnett, Images Courtesy of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation

NEW YORK CITY — The special exhibition featured in the Museum of Broadway, “The American Theatre as seen by Hirschfeld,” curated by David Leopold, creative director of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation, is now on display through April 30. Created exclusively for the Museum of Broadway, the exhibition takes visitors through nine decades of Hirschfeld’s iconic images of theater in the United States with 25 drawings and prints from 1928 to 2002. Visitors will be brought face to face with original production illustrations as well as a selection of sketchbooks that he used to record his initial impressions of shows in out-of-town tryouts and previews. There are also photographs of Hirschfeld on display throughout the exhibition, as befitting the man who historians have called “the logo of the American Theatre.”

Al Hirschfeld (1903-2003) was declared a Living Landmark by the New York City Landmarks Commission in 1996, and a Living Legend by the Library of Congress in 2000. Just before his death in January 2003, he learned he was to be awarded the Medal of Arts from the National Endowment of the Arts and inducted into the Academy of Arts and Letters. The winner of two Tony Awards, Hirschfeld was given the ultimate Broadway accolade on what would have been his 100th birthday in June 2003: the Martin Beck Theater was renamed the Al Hirschfeld Theater.

Hirschfeld’s drawings stand as some of the most innovative efforts in establishing the visual language of modern art through caricature in the Twentieth Century. A self-described “characterist,” his signature work is defined by a linear calligraphic style, and appeared in virtually every major publication of the last nine decades, including a 75-year relationship with The New York Times, numerous book and record covers and 15 postage stamps. He also authored several books and ten collections of his work. Hirschfeld said his contribution was to take the character, created by the playwright and portrayed by the actor, and reinvent it for the reader. “No one ‘writes’ more accurately of the performing arts than Al Hirschfeld,” playwright Terrence McNally wrote. “He accomplishes on a blank page with his pen and ink in a few strokes what many of us need a lifetime of words to say.”

Barbara Streisand in Funny Girl sees the reflection of the real Fanny Brice in the mirror, 1964.

The exhibition coincides with the publication of The American Theatre As Seen By Hirschfeld 1962-2002, the largest collection of Hirschfeld’s theater work that has ever been released. When a first volume of The American Theatre As Seen By Hirschfeld was published in 1961, Hirschfeld himself organized the book, featuring 250 works from the first 40 years of his career. Edited by Leopold, the creative force behind both the new book and the exhibition, this edition features a foreword by Michael Kimmelman and chapter introductions by Brooks Atkinson, Brendan Gill, Maureen Dowd, Terrence McNally and Jules Feiffer. Nearly 300 Hirschfeld drawings both show and tell the story of nearly a half century of the American theater, many of which have not appeared in previous collections. The American Theatre presents Hirschfeld’s greatest theater work from five decades, including some of the most important productions from the last 60 years, and takes you backstage with portraits of playwrights, directors and figures from all levels of production. Just before Hirschfeld died in 2003, he planned a sequel that would cover the other 40 years of his career, but the project was shelved with his passing until now.

Beginning his career in what would become the Golden Age of entertainment, illustration and print media, Hirschfeld was flush with opportunities in the 1920s when the art for theater and movie posters was still a hand-drawn business. His first caricature appeared in 1925 and Hirschfeld began his long collaboration with The New York Times in 1928. According to Leopold, “When Hirschfeld did his first theatrical drawing in 1926, he was already doing illustrations for two other newspapers, six film studios, as well as many books and magazines. He had an almost limitless capacity for work. It’s not that the drawings came easy, he was just very disciplined. He thought that talent was a drug on the market, and that discipline was what separated those who you knew about from those who you didn’t.” Leopold notes that when Hirschfeld was drawing Broadway, the “Arts & Leisure” section was still the “Drama” section. Hirschfeld was active at the advent of screen-based entertainment, illustrating for film and later television productions. “The first half-century of television is all recorded by Hirschfeld,” added Leopold. “He drew more covers of TV Guide than any other artist.”

Leopold has spent more than 30 years studying Hirschfeld’s work, the first 13 as his archivist, visiting him in his studio once or twice a week, and is now the creative director for the nonprofit Al Hirschfeld Foundation. Leopold has earned rave reviews from audiences around the country for his illustrated presentations. Leopold shared with Antiques and The Arts Weekly how he first encountered Hirschfeld and his world of entertainment while growing up in central Pennsylvania, “I discovered Hirschfeld like many people did… my parents showed me his drawings in The New York Times and told me about the hidden ‘NINAs.’ I did this for a couple of years before I asked myself who was in the drawing and what were they doing, and I think it’s an initiation rite into the world of show business and American art… For so many of us at the time, you felt like you knew something, even though everyone understood it.”

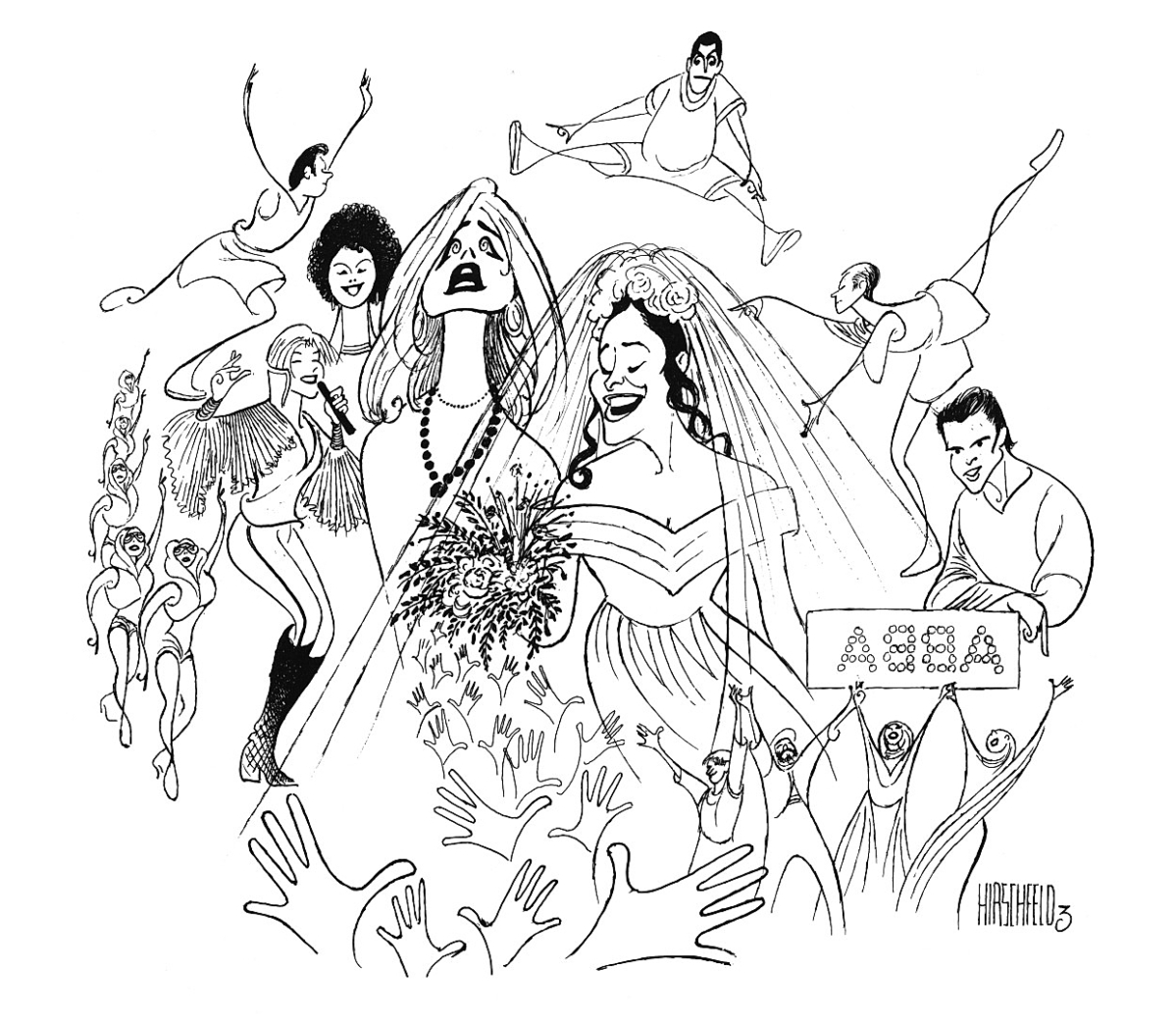

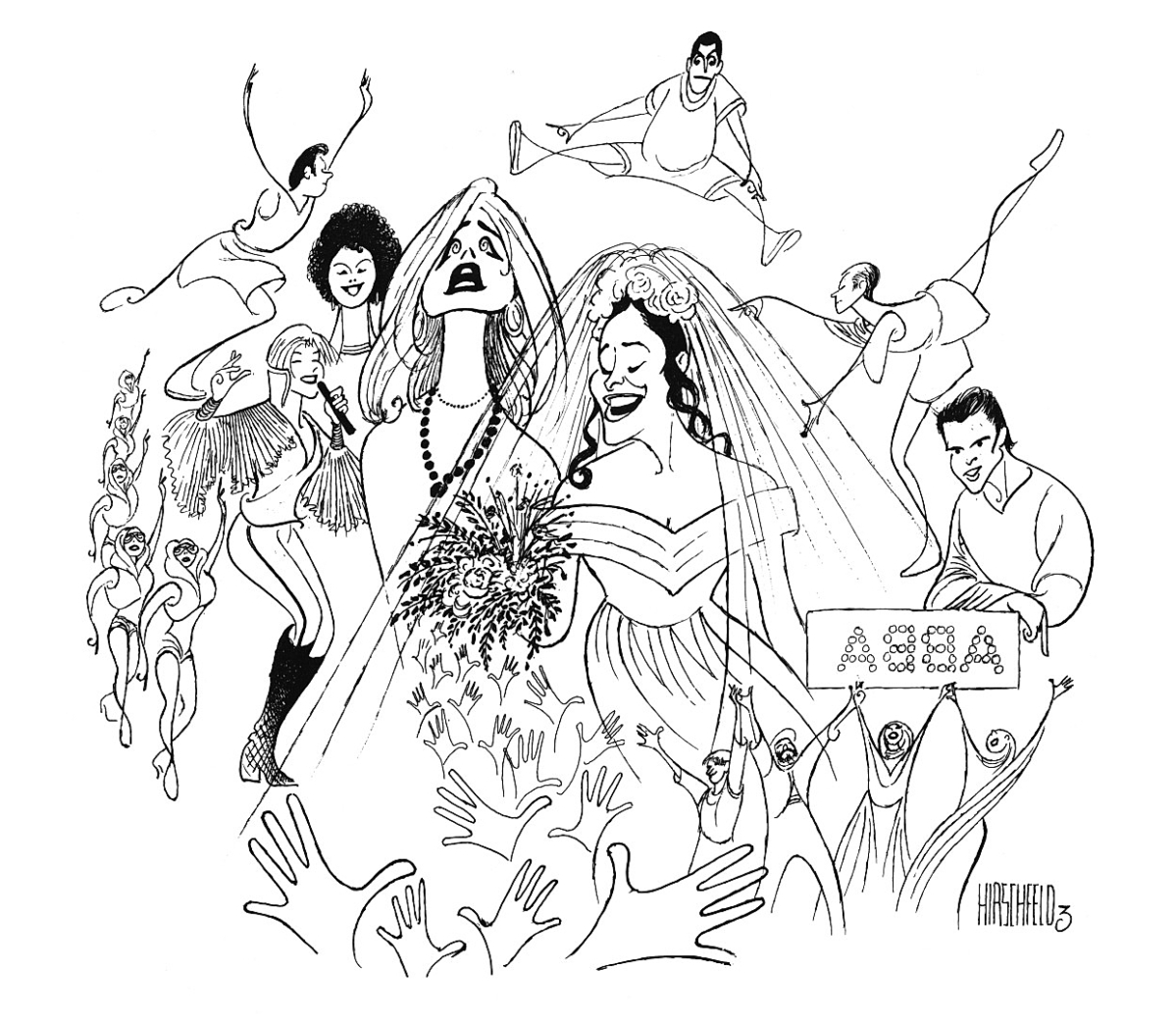

Mamma Mia! with Louis Pitre and Tina Maddigan, 2001.

Leopold’s preliminary encounter with Hirschfeld himself is cinematic in its own way. He first contacted the artist while researching one of Hirschfeld’s contemporaries after finding his information in, where else, the phone book. “I was too shy, I was 23 years old, and I thought, ‘One doesn’t just call Al Hirschfeld,’” recounted Leopold. “So I wrote him a letter, and he responded with probably the warmest letter I’ve ever received from [a non-family member]. He invited me the next time I was in ‘Fun City’ to come up and ‘quaff some tea,’ so I did!” Leopold later became Hirschfeld’s archivist, organizing his drawings and working with other researchers on the artist’s behalf. Hirschfeld would refer eager scholars to Leopold, joking, “He’s put everything in order now, and I can’t find anything.” Dry sense of humor aside, Leopold says, “Hirschfeld never treated me as anything other than a peer, despite the fact that he was three times older than me.”

Hirschfeld and Leopold developed a personal and professional relationship up until the artist’s death, working alongside one another through major events in both of their lives. Leopold shared, “Hirschfeld lived completely in the present, what was opening later that week or later in the season. But his past was just something that happened, stories to tell… I met him when he was 86 years old, so when you’re at that age and you’ve been doing the work he’s doing for 66 years, everybody wants to ask, ‘What’s your favorite of this or that?’ He didn’t think that way. So, he hired me to think about his past.”

Hirschfeld believed that “caricature” was the wrong way to describe his work. “When we think of caricature, it’s rarely in a positive way. It’s pejorative, it’s a put down, you’re laughing at the person,” says Leopold. “Hirschfeld’s work doesn’t use anatomical distortion, big heads, little bodies, he uses exaggeration for emphasis rather than denigration. You’re really laughing with the subject rather than at the subject. Hirschfeld saw himself as taking the character created by the playwright and portrayed by the actor, and he would reinvent it for the viewer. He was looking for the character of the show or the character they were trying to portray. I think he preferred the word ‘characterist’ because that’s what he was really doing, he was drawing the character,” Leopold continues. “You can look in the new book and, even if you don’t know any of the people, you see a parade of characters that might have only been possible in the theatre.”

At first glance, Hirschfeld’s drawings seem simple, but become more and more sophisticated the longer one spends time with them. Leopold describes Hirschfeld’s work as a reflection of the artist, himself, “Hirschfeld studied human beings like very few people have, and he had this wonderment of his fellow man [that he never lost], and certainly of the theater. He was as excited as anybody when the curtain went up.”

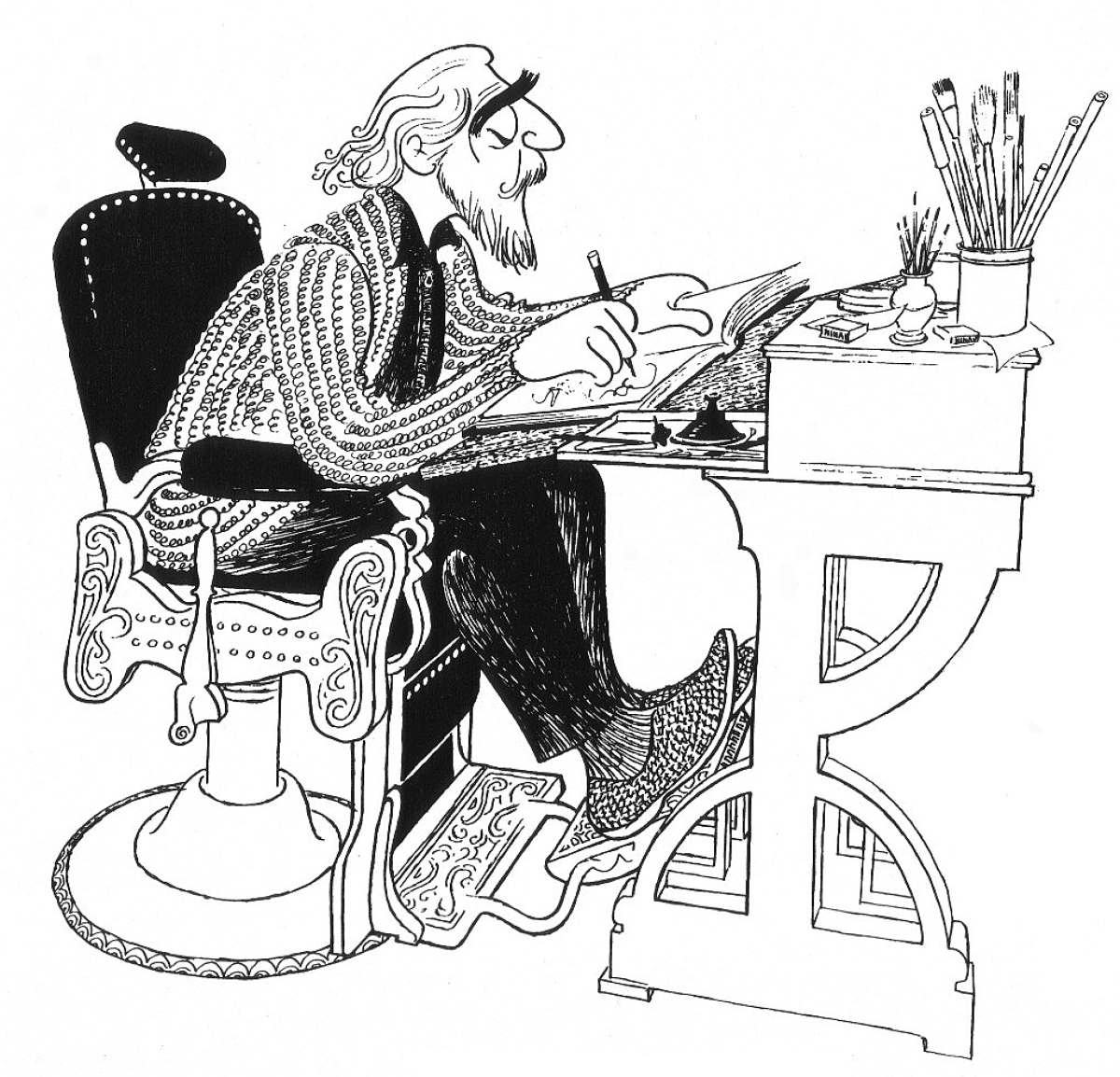

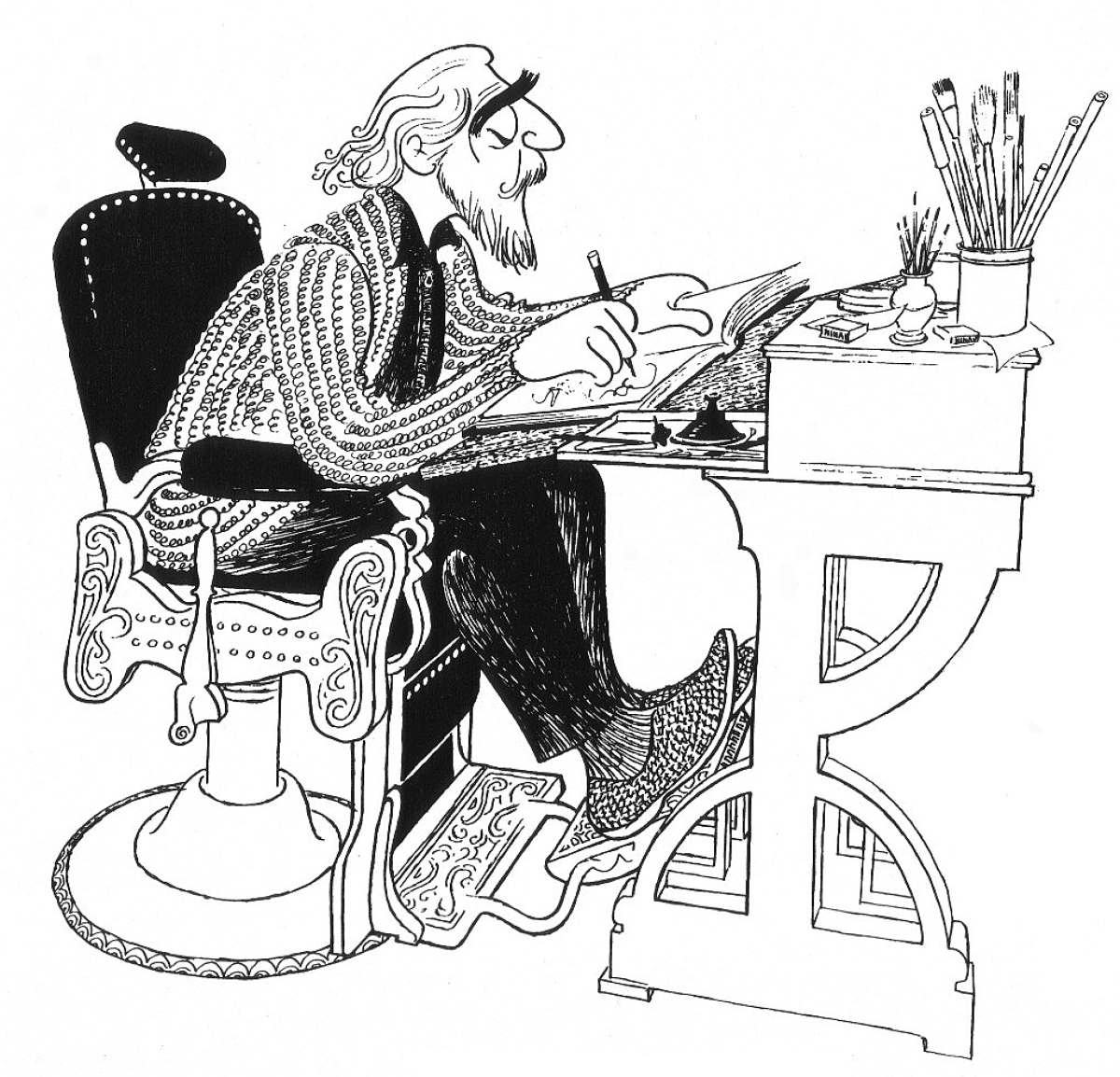

Self-portrait in barber chair, 1989. “Hirschfeld thought that the barber chair was the last functional chair in America,” Leopold shared with a smile. “It could go up and down, swivel, and when you wanted to take a nap, it could turn into a chaise longue.”

The world of entertainment has changed significantly since Hirschfeld’s last illustration, but this does not in any way render his work irrelevant as new generations are learning about the theater and the arts through the efforts of the Al Hirschfeld Foundation. Leopold has had a front-row seat to the ways in which the perception of Hirschfeld’s work has changed, and how viewers appreciate the artists and figures that he chronicled. “I actually think young audience members today see Hirschfeld’s work much more like he saw it than you or I see it. He was looking to create a drawing that could stand on its own two feet, that could withstand its topical news value. We’re not privy to that because we bring so much other experience to the drawings, whereas young people are not encumbered by that, so they’re reacting to the drawing itself,” he explains. “What we’re learning is that young people love Hirschfeld for the same reason we all do, that is because they’re compelling. The reason why he was so popular is because you feel compelled to look at them.”

The Al Hirschfeld Foundation has digitized more than 7,000 files of Hirschfeld’s work on its website with about 30 percent of his catalog remaining, excluding undiscovered works that remain in private collections. The foundation also created an app for the exhibition that allows visitors to “draw their own Hirschfeld.” Leopold explains, “Hirschfeld drew thousands of people throughout his career, and we created a palette of eyes, noses, mouths, so now you can ‘draw’ your own Hirschfeld and send it to yourself. In that sense, there’s a whole new generation of ‘Hirschfeld’ drawings coming out.” He continues that Hirschfeld had a “small D” democratic approach to his art. While Hirschfeld’s colleagues were trying to be featured in the most sophisticated publications, his work was five stories high in Times Square outside the Astor Theatre, giving joy to the public at large. The foundation also produces and performs shows in smaller-sized museums across the country and created an arts education program with the New York City Board of Education that has since become accessible online for underfunded school districts.

“I always say that everything we do should be like a Hirschfeld drawing and leave a smile on people’s faces, because you look at them and can’t help but smile,” Leopold said. “Maybe because you recognize the performer, and you love the way that he’s drawn them or the funny way that he’s done it. But mostly it’s like any great drawing, it makes you feel better. And his drawings do that.”

The Museum of Broadway is at 145 West 45th Street. For information, 212-239-6200 or www.themuseumofbroadway.com.