Beauport’s Belfry Chamber with Zuber’s 1832 Décor Chinois wallpaper. Built 1911-1912.

By Madelia Hickman Ring,

MILTON, MASS. — Emily Post wrote, in Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home (New York, 1922), “A bachelor’s house has a something about it that is very comfortable but entirely different from a lady’s house, though it would be difficult to define wherein the difference lies.”

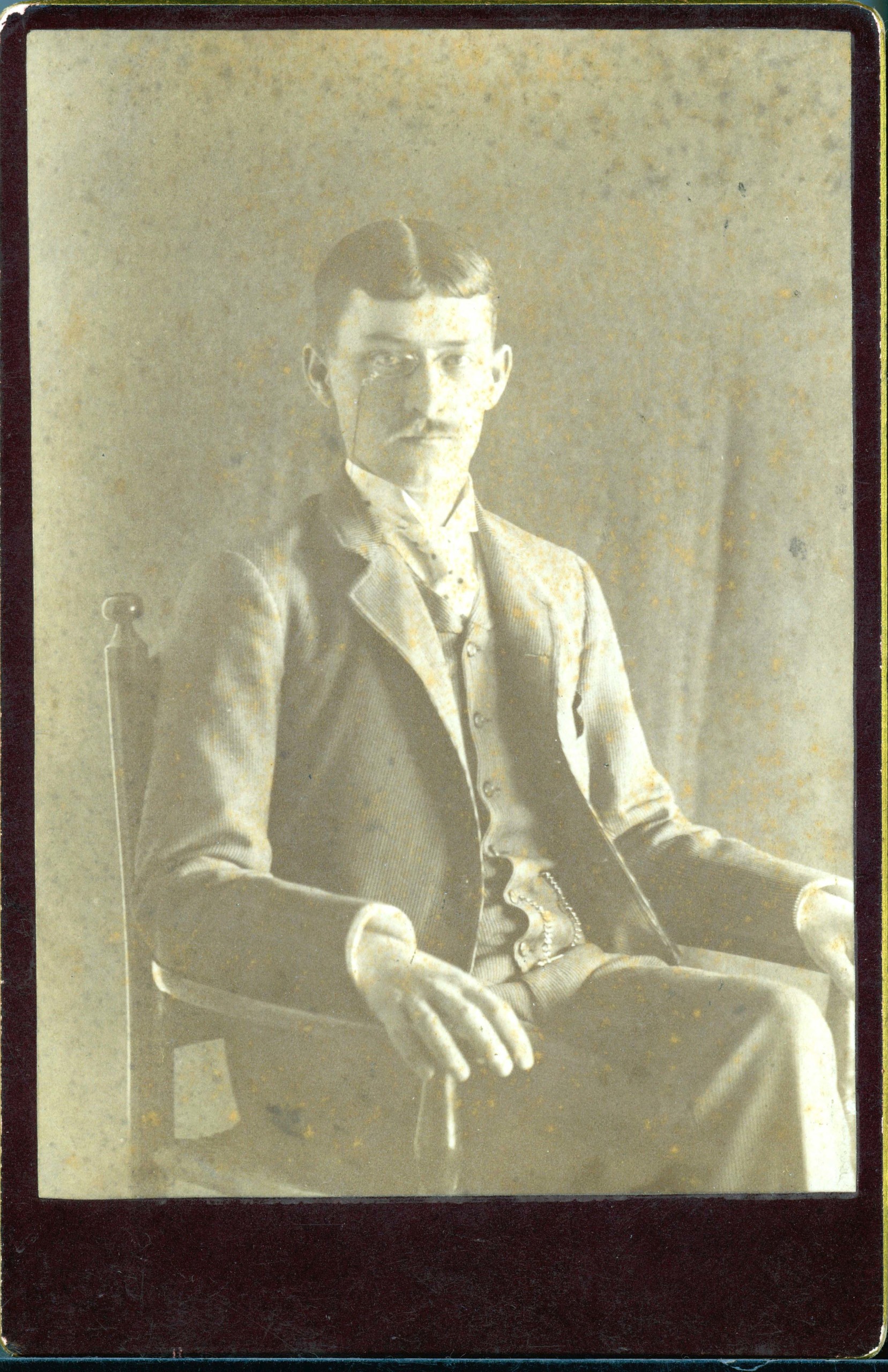

A new exhibition at Historic New England’s Eustis Estate, “The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home” takes up Post’s quote almost like a challenge. In the exhibition, which is on view through October 27, the lives — and lifestyles — of four largely contemporary Nineteenth Century New England bachelors are examined. Exploring not only stories of four historic homes and their creators — Charles Leonard Pendleton (1846-1904), Ogden Codman Jr (1863-1951), Charles Hammond Gibson Jr (187-1954) and Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934) — the exhibition also takes a deep dive into the evolution of American interior design and the role each played in developing the burgeoning field of American interior design. In the process, contemporary assumptions and historical inaccuracies are corrected.

The exhibition is curated by R. Tripp Evans, professor of Art History at Wheaton College in Norton, Mass., whose book by the same name was the basis for the exhibition. Evans shared with Antiques and The Arts Weekly that the idea for The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024) was inspired by a series of imaginary “family portraits” by contemporary artist Hannah Barrett at the Gibson House Museum in 2011.

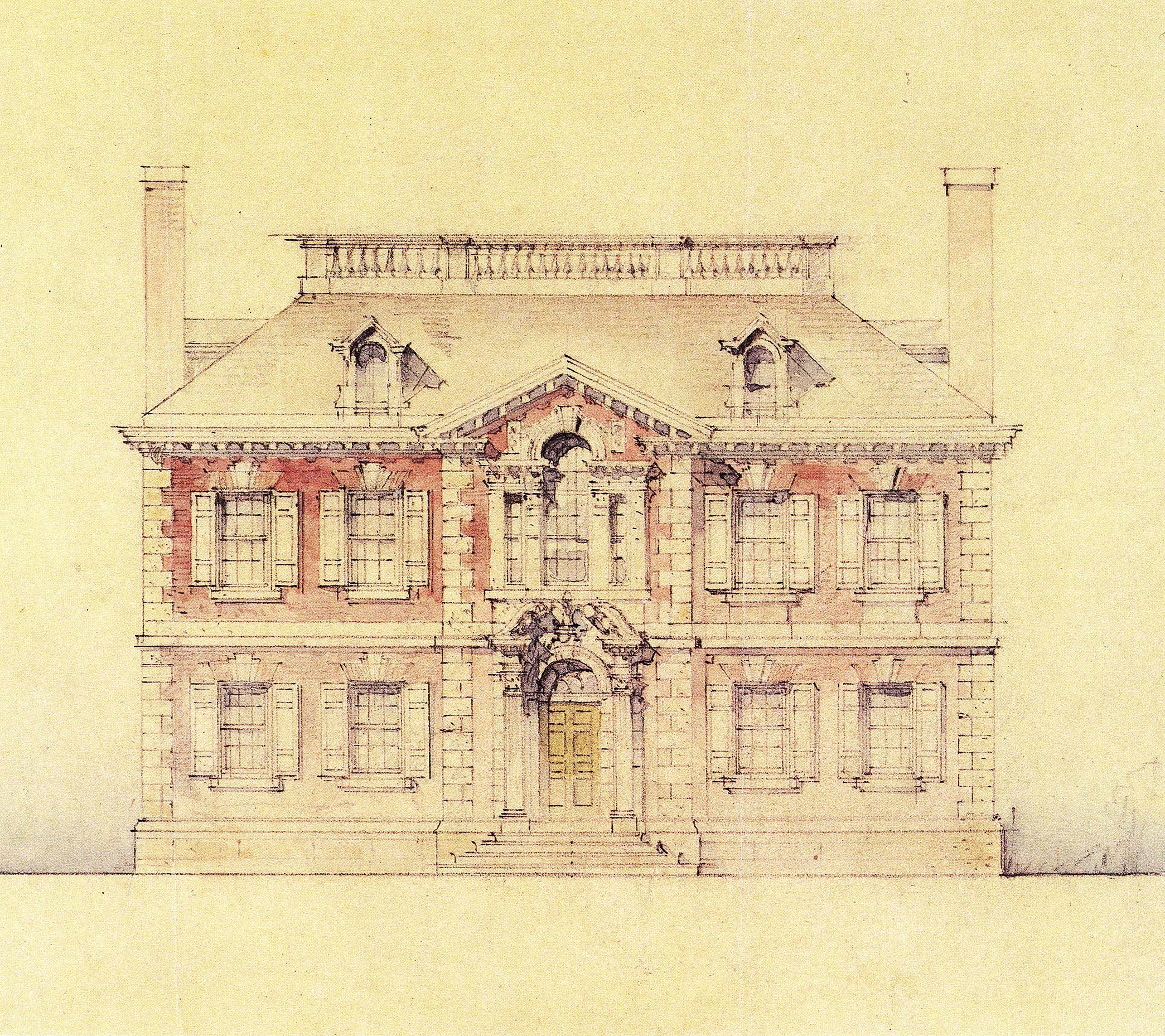

Charles Hammond Gibson Jr’s 1859 residence at 137 Beacon Street, Boston. Courtesy John Woolf, Gibson House Museum, Boston.

Evans writes in his introduction, that despite there being other men who fit the mold, he chose these four men because they all share the same period, region, class, social networks and vocation — all were involved, to lesser or greater degrees, in professional interior decoration.” For this reason, he “was able to cast their dazzling range of styles in higher relief.”

His intent was “to demonstrate that the era’s insistence on individual expression defied even the potentially leveling influence of their shared profiles.” In each case study, he writes, “We encounter a man whose story speaks to the period’s bachelor house phenomenon more broadly.” He defines the “bachelor house phenomenon” as “a convergence of factors — historical, literary, economic and sexual — that, for the first time in the modern era, established the single man’s household as an aspiration domestic model.”

Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), who spent much of 1882 on an American lecture tour, was, in Evans’ view, a critical driving force espousing the “art for art’s sake” message of the Aesthetic Movement, which also upheld the idea that “beauty” was an end to itself rather than as a vehicle for moral purpose. This was in direct contrast to the earlier Victorian ideal of the home as the place to nurture the Christian ideals of family and the purity of marital love. In fact, marriage was considered anathema to any bachelor who wanted to live comfortably.

The Red Study at 137 Beacon Street. Courtesy John Woolf, Gibson House Museum, Boston. Gibson House, Boston.

Evans explains further: “These houses were aspirational in the sense that, for many critics, a (well-heeled) bachelor’s home represented the purest form of individual expression. Without spouses or children, these bachelor-decorators had the freedom to create homes that reflected a singular artistic vision, which, according to Wilde, was the ultimate goal in home decoration.”

Visitors to the exhibition may be curious if there was a corresponding feminine aesthetic but Evans is clear to note that he found no evidence of how single women decorated. Additionally, he points out undertones of misogyny in period accounts that justify the bachelor aesthetic by attesting to the inability of women to create sensual or comfortable environments.

Does it matter that all four men were gay, or presumed to be so? Evans makes a strong circumstantial case in the book and exhibition, saying, “It would be irresponsible to ignore the points where the men’s decorating and sexuality coincide as it would be to suggest this alignment was experienced similarly by them all. However varied their experiences might have been, the choices they made as designers and collectors greatly depended upon their relationships with those who crossed their threshold — and not least with those who shared their hearts and beds.”

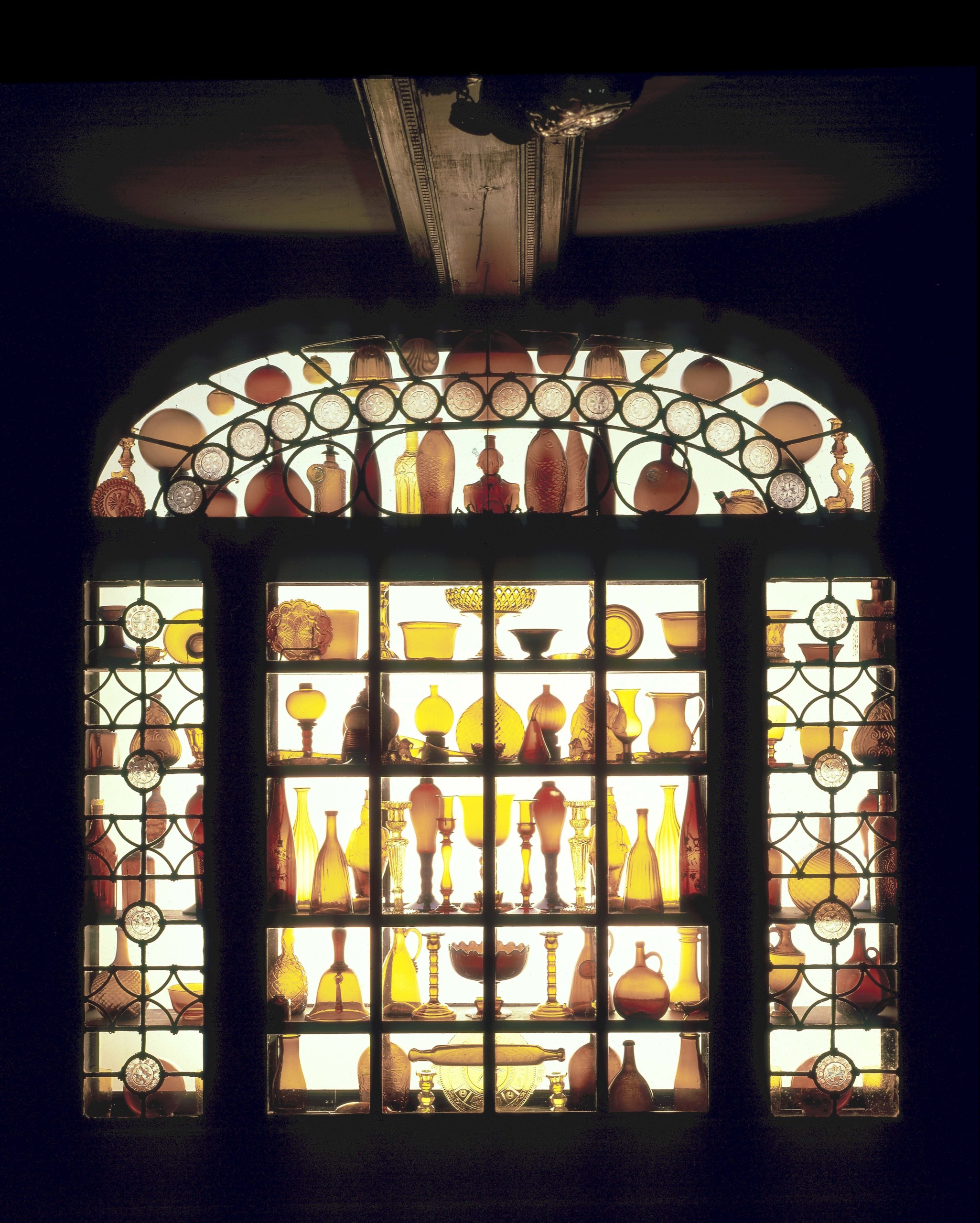

The Codman Estate, circa 1740, Lincoln, Mass. David Bohl photo courtesy Historic New England.

Of the four bachelor studies, Codman stands out the most for his contributions to the field of interior decorating. As a professional decorator and occasional architect, he had several Gilded Age and Edwardian-era clients from the 1890s to 1920, including his early commission for the Vanderbilt family in 1893-95. He co-authored The Decoration of Houses (1897) with Edith Wharton, a hugely popular treatise that Evans notes established Codman as “one of his period’s greatest tastemakers.” Codman’s friend, the architect Arthur Little, encouraged Sleeper’s interests in decorating; Sleeper would go on to work for the Vanderbilt family in the 1920s and 30s, Henry Francis du Pont and Hollywood clients such as Joan Crawford. Among aesthetic contributions would be Sleeper’s practice of mixing high- and low-valued works and collecting American folk art.

The exhibition features many never-before-exhibited pieces from the men’s homes, as well as historic photographs, paintings, drawings and ephemera. Together, these works illuminate the private worlds of Codman, Gibson, Pendleton and Sleeper as well as those they created for clients.

The book and exhibition contest the idea that collecting is either a form of suppressing unwanted or unacceptable urges, or the hoarding response to a loss. The homes of Pendleton, Codman, Gibson and Sleeper are celebrated for their expressions of creativity and joy and without negative connotations. Evans interprets the concept of being “at home” in several ways. Not only did bachelors derive pleasure and comfort from their surroundings but also the social status and power one achieved by being able to receive visitors. Having the means and impressively designed space in which to do so and being able to dictate who could visit were other ways one could be at home, but perhaps most importantly, it gave the bachelor a semi-public space to be “his most private self.”

“Henry Davis Sleeper” by Wallace Bryant, 1906, oil on canvas, 60-7/8 by 66¼ inches. Gift of Stephen Sleeper, 1941.1703. Courtesy Historic New England.

Given the evolution of the field of interior design and the near assumption that many current male interior designers are gay, one cannot help but wonder what Codman, Gibson, Pendleton and Sleeper would think of the world today.

“The Importance of Being Furnished: Four Bachelors at Home” will be on view at the Eustis Estate, at 1424 Canton Avenue in Milton, through October 27.

For information, 617-994-6600 or www.historicnewengland.org.