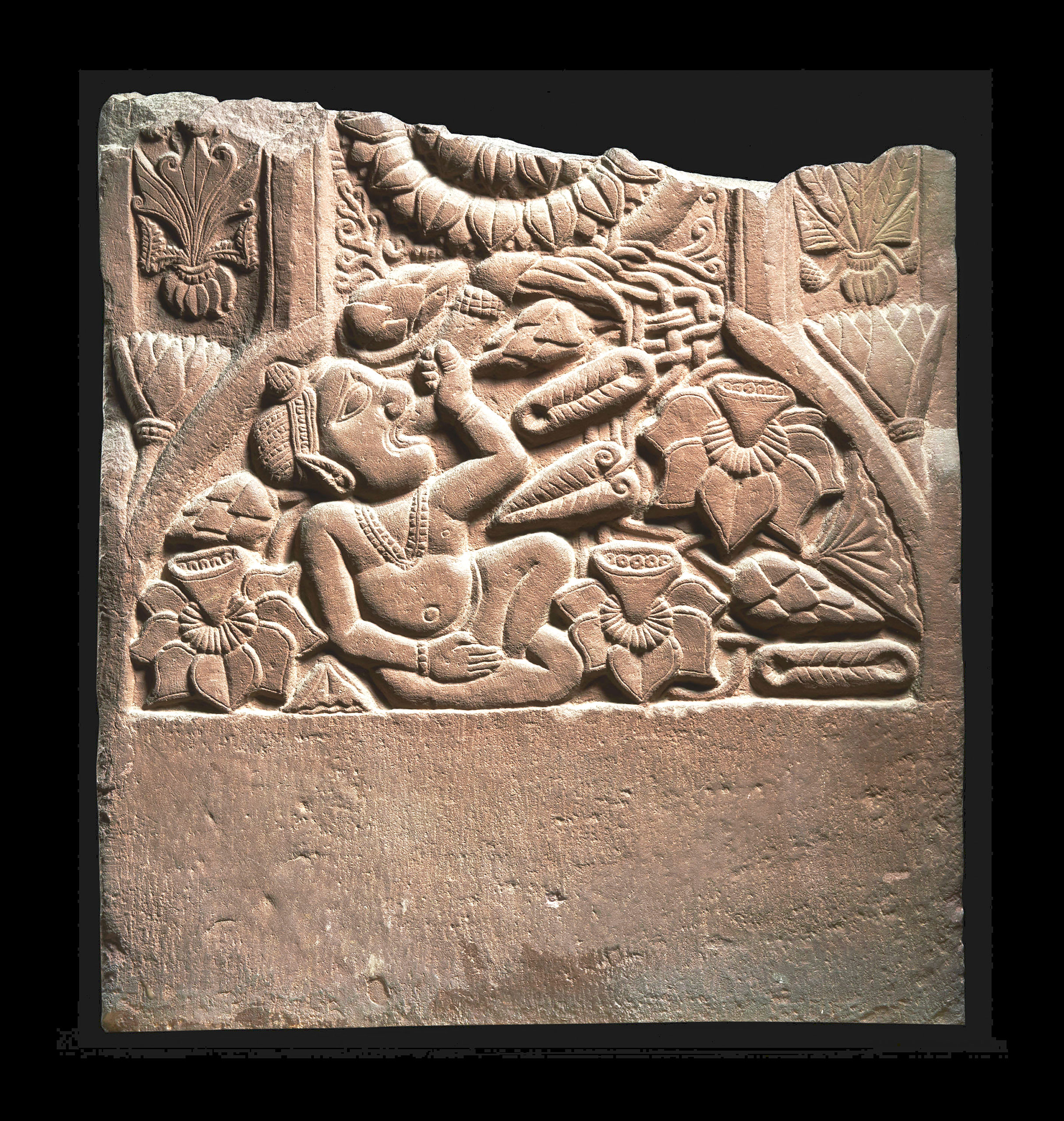

King Puluvami surrenders the city of Ujjain, Kanaganahalli stupa, Karnataka Satavahana, early Second Century CE, limestone. Collection: Kanaganahalli Site Museum, Archaeological Survey of India.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY — The relationship between ideology and art, between visual culture, the spread of doctrine and the assertion of power is well-documented. Rome, for example, assimilated the deities of conquered peoples conquered into its imperial theogony. What makes “Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE-400 CE,” the new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, so intriguing is that the first great flowering of Buddhist art occurred not in the north of the Indian subcontinent, in the foothills of the Himalayas where Buddha lived and where the faith that bears his name was born, but further south, in what is called the Deccan, which lies roughly between the Godavari and Krishna Rivers. Beautiful limestone monasteries (viharas), elaborately carved with Buddhist narratives, deities and symbols sprang up, surmounted by elegant, imposing funerary mounds (stupas), beehive- and bell-shaped structures housing relics of the faith. The sheer number of viharas and the beauty of the objects in the exhibition — despite the many gaps in the record and in our understanding of the historical dynamic — suggests that Buddhism dominated the Deccan with relative ease. Yet, as the catalog text asserts more than once, “in India; the sacred landscape has always been contested.” Buddhism had to contend with fully developed faiths such as Brahminism (which we often call Hinduism) and Jainism, as well as scores of local traditions, each with its own gods and practices.

Gateway architrave with makara, Bharhut stupa, Satna district, Madhya Pradesh, Sunga, circa 150-100 BCE, sandstone. Collection: Indian Museum, Kolkata.

The works in the exhibition as well as the essays in the comprehensive catalog ask us to imagine a network of viharas, not only as sites of Buddhist ceremonies and meditation but as rest stops and hostels for travelers and merchants — who often became converts and donors — and as marketplaces for the thriving commercial trade between southern India and — to circle us back to the first sentence in this essay — Republican and Imperial Rome. Indeed, the dates of Buddhist flourishing in the Deccan correspond neatly with Rome’s power at its height. But its beginnings really lie with the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka (268-232 BCE), who supported not only Buddhism but other faiths as well and initiated scores of edicts designed to encourage respect for all living things. He also endorsed the construction of viharas and stupas, which became crucial way stations for travel and trade. Ashoka’s interpretation of Buddhist Dharma, or Dhamma, adapts the faith’s “Middle Way,” that is, a path to enlightenment between strict asceticism and renunciation of the world and a materialistic view. His symbol, the wheel, derives from the Dharma-wheel, a symbol “shared by mythological universal emperors (cakravartin), who cause the wheel of justice and good governance to roll, just as Buddhas set in motion the wheel of the Dharma” (cat., p. 79), that is, his teachings and manifestations in the world. Linking of Buddhism with good governance and right action radiating from a central hub extends even further into the world, and into trade, where the wheel — originally a wagon wheel — signifies the merchants’ carts that rolled from community to community, finding shelter in the viharas that dotted the way. The wheel is often seen inside carved footprints that mark the Buddha’s path and the spread of his teachings. Peripatetic monks and traveling traders found common cause; grateful traders often made hefty donations that maintained the viharas and their inhabitants as well as funding new construction.

“Panel with devotees honoring the Dharma-wheel and nagas protecting the relics at Ramagrama stupa” tells the story of the serpents (nagas) who watch over a Dharma-wheel that floated down to them after a flood, while “Stupa drum panel with protective serpent,” from one of the most important viharas at Amaravati, offers an elegant, schematic overview of one of these massive, bell-shaped reliquaries, adorned with the serpent and set against a tree, the two images that form the core of idea of the exhibition.

Stūpa panel with nāgarāja Mucalinda protecting the Buddha footprints, Dhulikattā stūpa, Karimnagar district, Telangana, Early Sātavāhana, First Century BCE, limestone. Inscribed in Southern Brāhmī Prakrit: “Gift of Samā, mother of the notable gahapati.” Collection: Karimnāgar Archaeology Museum

In his catalog essay, John Guy describes “the religious landscape of early India” as “already densely populated with spirits and demigods. They resided in all the natural forms — trees, rocks, rivers and ponds — in which they were understood as omnipresent and phantomic presences, able to reveal themselves at will. Buddhist canonical texts speak of places sacred to yaksas and yaksis, the male and female nature deities, along with those of deified snakes, nagas and naginis, and of platforms and shrines dedicated to their veneration, suggesting that their icons and places of worship existed in the Buddha’s lifetime” (cat. p. 19). What the exhibition reveals is Buddhism’s adaptation to — and appropriation of — the existing religious landscape. Nagas become guardian spirits in the stupas, while the yaksas and yaksis, demonic local deities that required constant appeasement, evolve into gargoyle-like male figures that generate the lotus, as in “Railing pillar fragment: yaksa with lotus vine emerging from mouth” and voluptuous female entities such as “Yaksi, nature spirit celebrant.” Each of these impish nature demons now serves the Buddhist wheel of life as positive symbols of fertility and the bounty of the natural world. On the other hand, the transition of the tree from local, animist symbol to representation of the Buddha was much easier. Buddha was born beneath a tree, enlightened beneath a tree, and achieved nirvana at the base of a tree.

One of the most astonishing aspects of the exhibition is the correction of the popular notion of Buddhism as antithetical to commerce. Buddha himself knew that each sangha, or community of monks, needed to sustain itself, and that the buying and selling of staples, such as rice, was allowed as long as profit was not the only motive. Each sangha appears to have had a business agent who kept records of purchases, sales, and donations. Rule were strict, but monks must be fed and monasteries and stupas must be maintained and built. As with so much in the exhibition, this is a new area of investigation, one that will surely fascinate as it continues to be explored.

And so will our understanding of the relationship between India and Rome in this period.

Poseidon (after Lysippos), Alexandrian Roman, First Century CE, copper alloy, 5-7/8 by 11-5/16 inches. Excavated at Brahmapuri, Kolhapur, Satara district, Maharashtra, 1944-45. Collection: Town Hall Museum, Kolhapur, Maharashtra.

For a very long time, our understanding of the trade between India and Rome concentrated on the land route known as the Silk Road, but in recent decades, scholars have learned a great deal more about the robust maritime exchange between ports in Southwest India and Rome, which began in earnest during the reign of Augustus Caesar. Spices, especially Malabar pepper, cinnamon, ginger, clove and cardamom became staples in Roman kitchens and were carried by Roman legions. Wealthy Romans wore Asian jewels fashioned from Asian onyx and ivory. In India, Italian “ceramics, glassware and bronze statuettes like the miniature Poseidon discovered in Kolhapur” (cat. p. 160) abounded. Coins of the empire have been excavated all across the subcontinent. As for Buddhist involvement in the Rome-India trade, Roman names appear as donors in inscriptions on viharas but the field of inquiry remains relatively new. What is true is that trade made Indian merchants wealthy and that their wealth made the network of viharas and stupas possible and that Rome’s decline, which signaled the eventual end of commercial and cultural exchange, coincides with the decline of Buddhist influence in the Deccan.

Before this, however, and perhaps as a result of the cultural cross-pollinations that accompanied brisk trade, scenes from the life and lives of Buddha become more prominent in statuary and on the carved reliefs in the viharas. The figure of Buddha himself, seen at first only symbolically, through the wheel, footprints and other images, is now represented as a human being, gradually assuming the aspect of the figure we have come to know — robe draped over one shoulder, small smile, hand raised in benediction. For instance, there is something familiar about the “Standing Buddha” from the Third Century CE, as if the sculptor has combined the stylized stillness of Egyptian and Persian figurative sculpture with the draperies of Classical Greece and harmonized them in a South Asian facture that survives to this day.

Standing Buddha Nelakondapalli, Khammam district, Telangana Iksvaku, Third Century CE, limestone. Collection: State Museum Hyderabad. Department of Heritage Telangana.

As with so many civilizations and cultural flowerings around the world, the viharas and stupas were gradually abandoned and fell into disrepair. The limestone structures and sculptures succumbed to time, weather, and the needs of newcomers for building materials — which were readymade. So much was broken up, lost, repurposed. One wonders what the future will unearth of us and our times. Perhaps history is very much like the reliquaries that remained unopened and unobserved at the heart of the stupas. Visitors had to imagine them. One such reliquary, however, was excavated in 1898. “Relics from the Piprahwa stupa” includes little pieces of gold, glass, stone, crystal, pearl and shell — all associated in ways obscure to us at this remove. And so, while we can take in their delicacy and appreciate them, their meaning is as distant from our reality as their presence was to those who walked the stupa when it was bustling. Perhaps, in order to begin to understand history, we have to imagine our way into history first.

Extend the metaphor of the tree and serpent, give them a more modern spin, and one sees in them — and the Buddhist Deccan — the great compromise that always obtains when systems of belief that advocate renunciation of the world simultaneously require engagement with the world in order to broadcast and propagate those beliefs. Extend this idea just a little further and one sees that it lies at the heart of the arts as well, where the compromise can be found between the artist’s intention and message and the need for some form of patronage to express and convey that message. To those of us who are not Buddhists, the “Middle Way” in Buddhism is nonetheless a powerful metaphor for the compromises — the balancing acts, if you will — that life compels us to make, even as we keep our eyes and minds on the spiritual wholeness we seek in our own identities. Still, if a compromise must be made, “Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE-400 CE” offers the image of a harmonious place to do so: strolling in a garden by a river beneath an umbrella, beside a bell-like stupa, or walking the path on the outside of the stupa, looking over the railing, breathing in the breathtaking landscape of creation.

“Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE-400 CE” will be on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 13.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For additional information, 212-535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org.