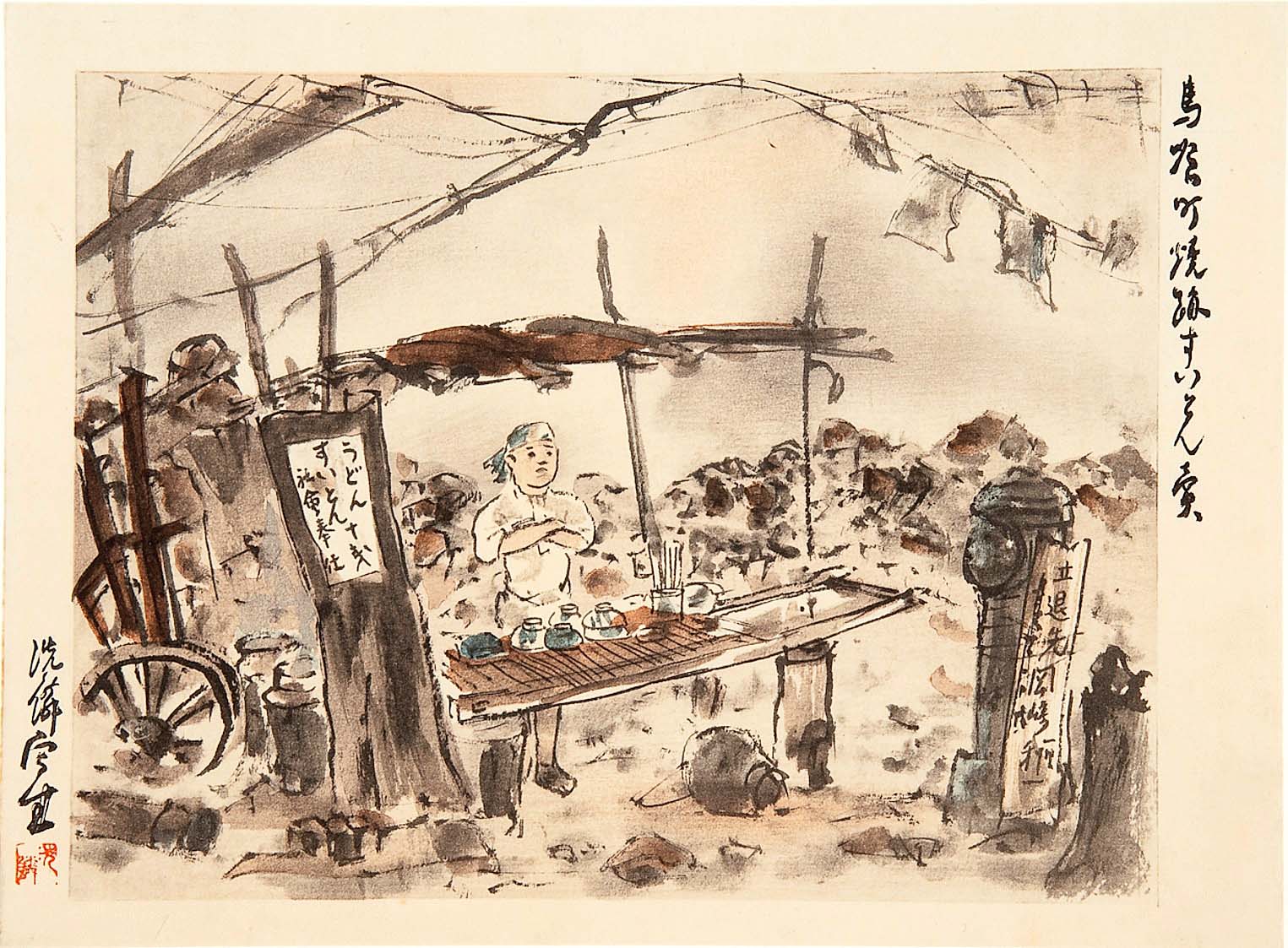

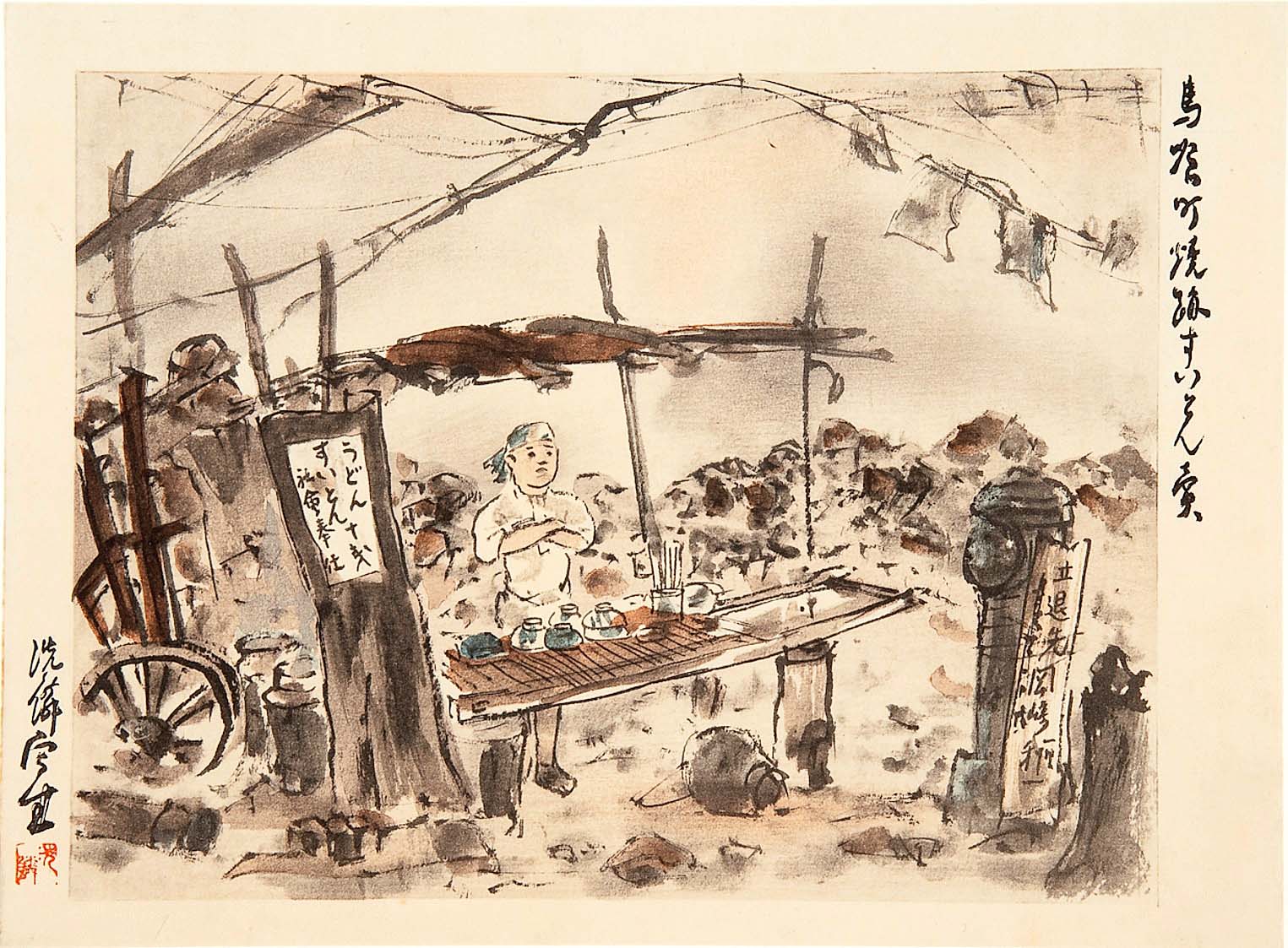

“Suiton Seller at Bakuro District (#20),” from the series “Pictures of the Taisho Earthquake” by Kiriya Senrin (1877-1932), Japan, 1926, woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Gift of Philip H. Roach, Jr, 2010 (31753).

By Kiersten Busch

HONOLULU — With its popularity in the US market only growing, it’s hard to find someone who hasn’t heard of the Japanese storytelling art form of manga, or its animated counterpart, anime. Even if you think you’re unfamiliar, I’m sure you or your children grew up catching a stray episode here or there of Pokémon (1997-) or Dragon Ball Z (1996-2003) on television networks like Nickelodeon on a Saturday afternoon; both are anime series that began airing in Japan in the late 90s.

It’s common to assume that anime such as these are solely marketed to children. They’re just as colorful and goofy at times as the average American cartoon (think Avatar: The Last Airbender or Voltron: Legendary Defender), they teach similar lessons and have a plethora of merchandise in the toy aisles of retailers nationwide.

This, however, is a common misconception about the anime and manga industry as a whole. In the last two decades or so, shōnen (a sub-genre of manga with a target audience of young boys and teenagers) has grown increasingly popular in the western market, with such series as Attack on Titan (Hajime Isayama, 2009-2021), My Hero Academia (Kōhei Horikoshi, 2014-2024), Jujutsu Kaisen (Gege Akutami, 2018-2024) and Demon Slayer (Koyoharu Gotouge, 2016-2020) flying off the shelves of major booksellers like Barnes & Noble and Books-A-Million. The clever, thinly-veiled societal commentary represented by fictitious nations, fantastical powers, bloody fights and meaningful sacrifices are a much-needed comfort to many teenagers and young adults in an increasingly tumultuous social and political climate.

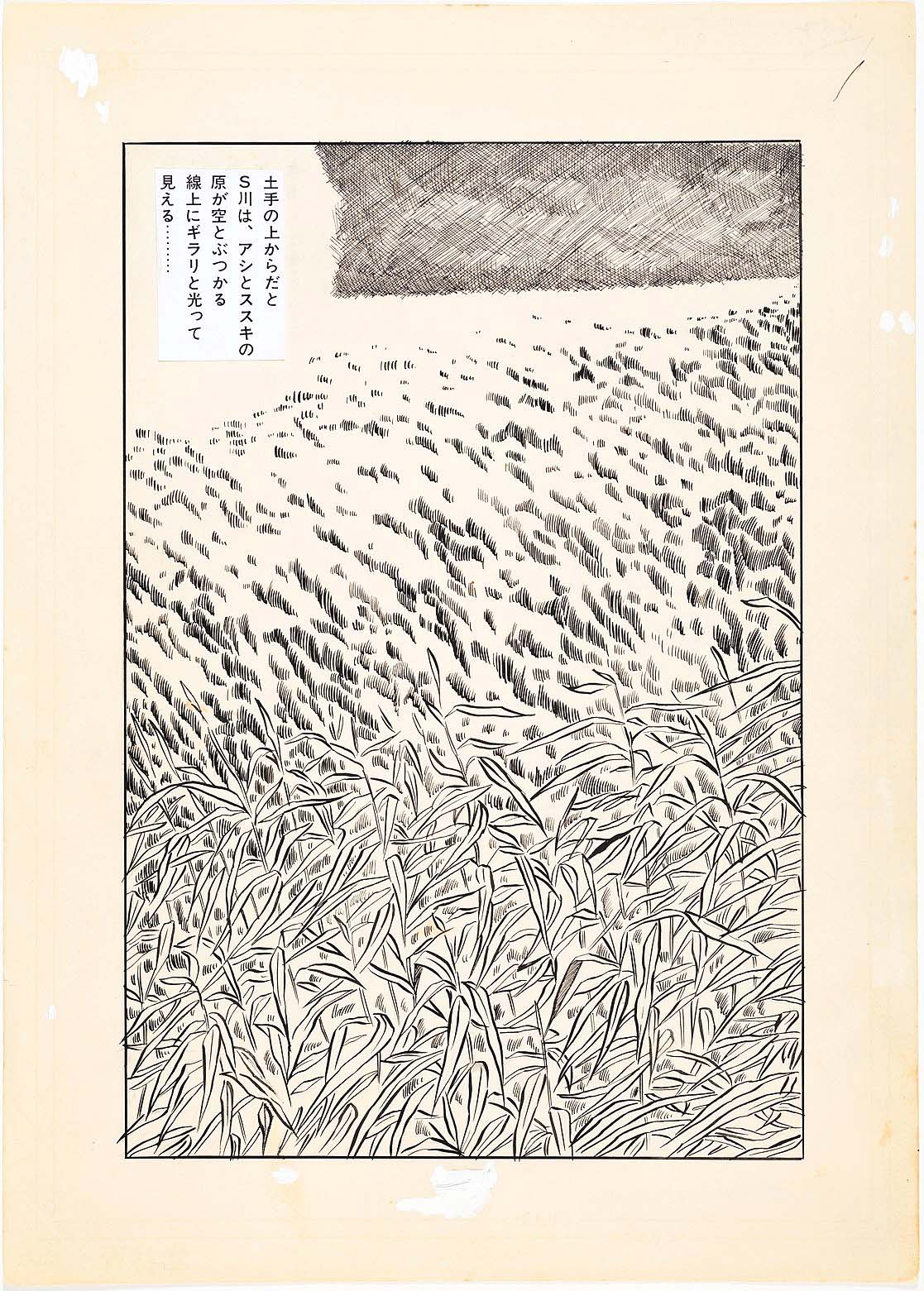

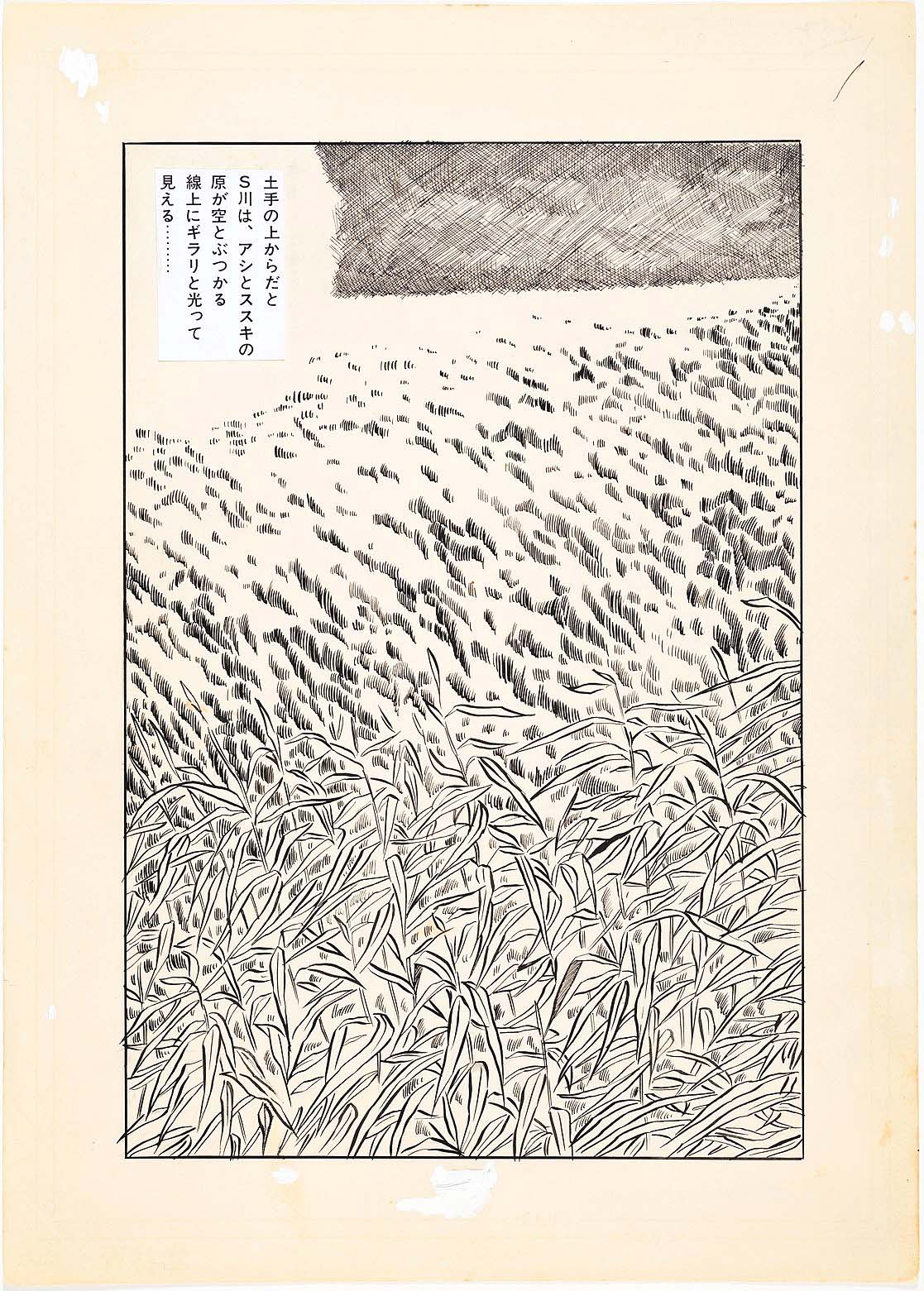

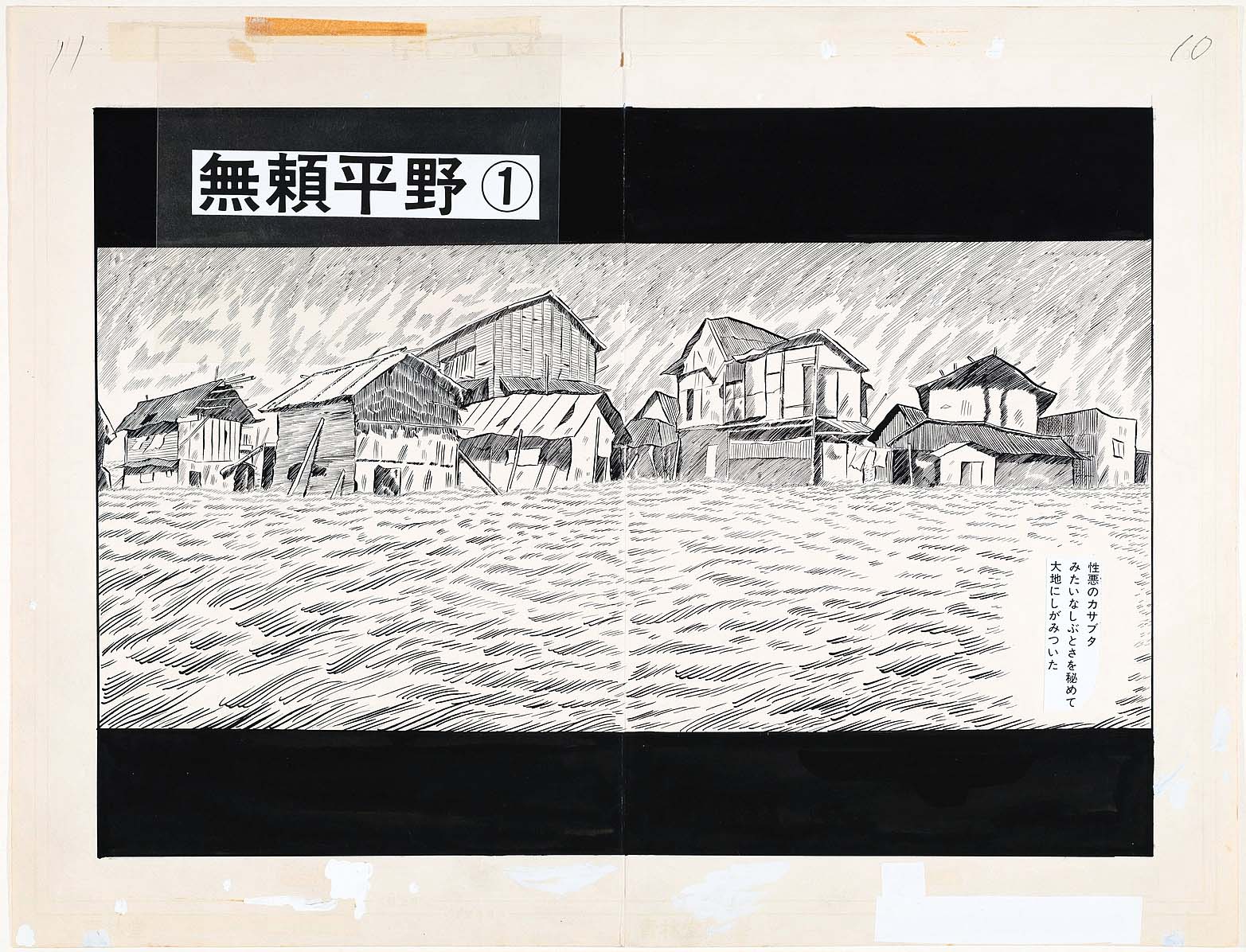

Page 1 from Vagabond Plain (Burai heiya) by Tsuge Tadao (b 1941) Japan, October 1975, hand-drawn comic art (genga); ink on paper. Purchase, 2019 (2019-5-01). Honolulu Museum of Art.

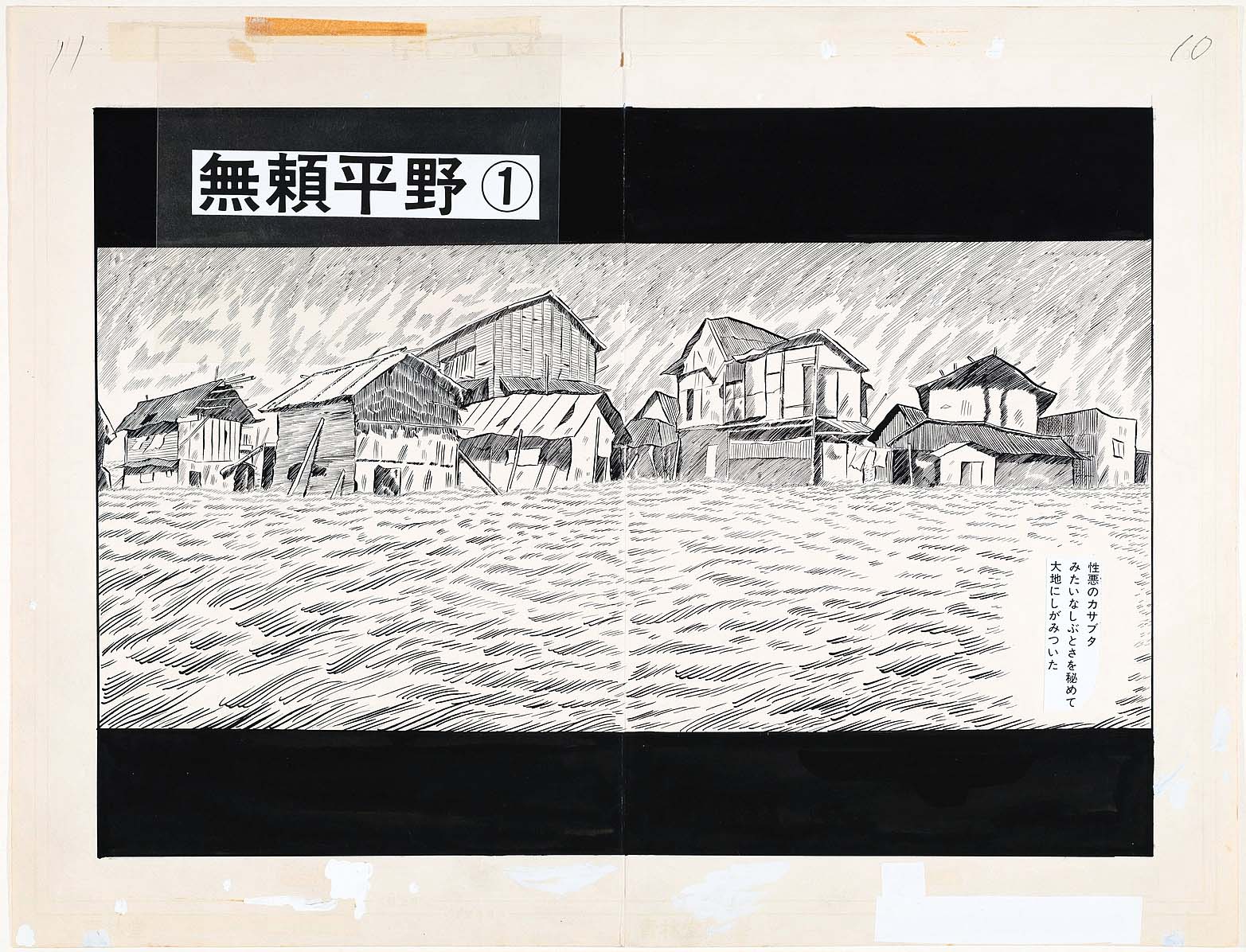

While fictional worlds are depicted quite frequently in manga, it is significantly rarer to find a body of work set in real-life Japan that offers that same type of societal criticism. This absence, and its few outliers, are what The Honolulu Museum of Art (HoMA) sought to explore with “Drawn from the Street: The Politics of Poverty in Postwar Manga.” The exhibition, which centers around 14 excerpts from the short story Vagabond Plain (Burai heiya) by Tadao Tsuge (b 1941), was organized by the HoMA’s Robert F. Lange Foundation curator of Japanese art, Stephen Salel.

Salel is a veteran when it comes to all things manga, having curated five previous manga-oriented exhibitions at the HoMA, all “addressing varied social issues,” he explained to Antiques and The Arts Weekly. The first, which ran from November 2014-March 2015, was titled “Modern Love,” and “discussed the contemporary legacy of early modern Japanese erotic art (shunga),” he shared. This was the catalyst for a follow-up exhibition, “Vision of Gothic Angels” (August 2016-January 2017), which spotlighted manga artist (or, mangaka) Takaya Miou. Then came “The Disasters of Peace: Social Discontent in the Manga of Tsuge Tadao and Katsumata Susumu” (November 2017-April 2018), where Salel “shifted [his] focus to political comics,” and, most recently, “Navigating a Minefield: A Manga Depiction of Japanese Americans in the Second World War,” which was a collaboration with local artist Stacey Hayashi and was on view from October 27, 2022-March 5, 2023.

The inspiration behind “Drawn from the Street,” according to Salel, was the museum’s acquisition of Vagabond Plain in 2019. The story highlights what the museum called “the problems of urbanization and socioeconomic disparity in Japan during the Allied Occupation (1945-1952), a story that was largely overshadowed in the media by what is known as the ‘economic miracle.’”

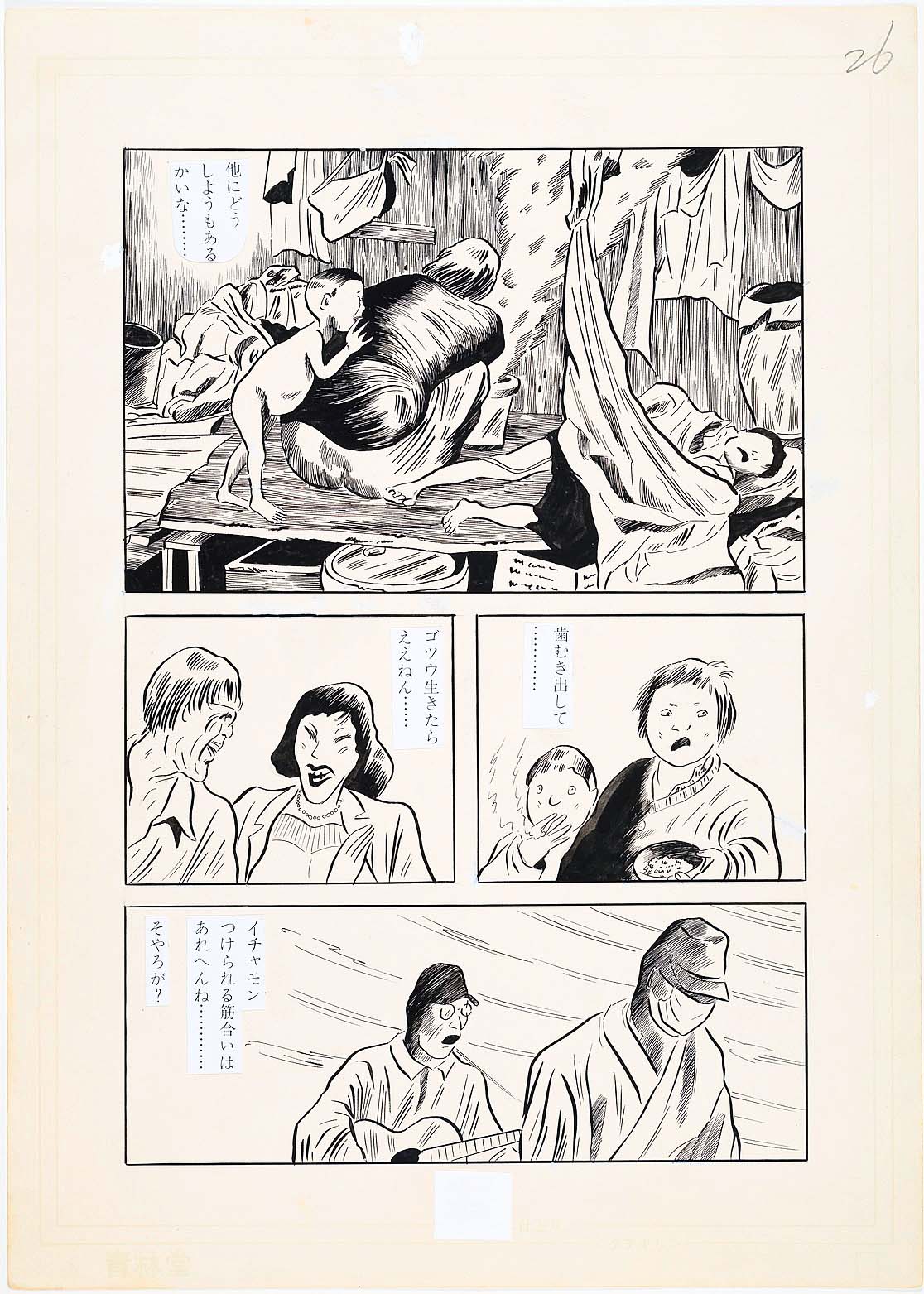

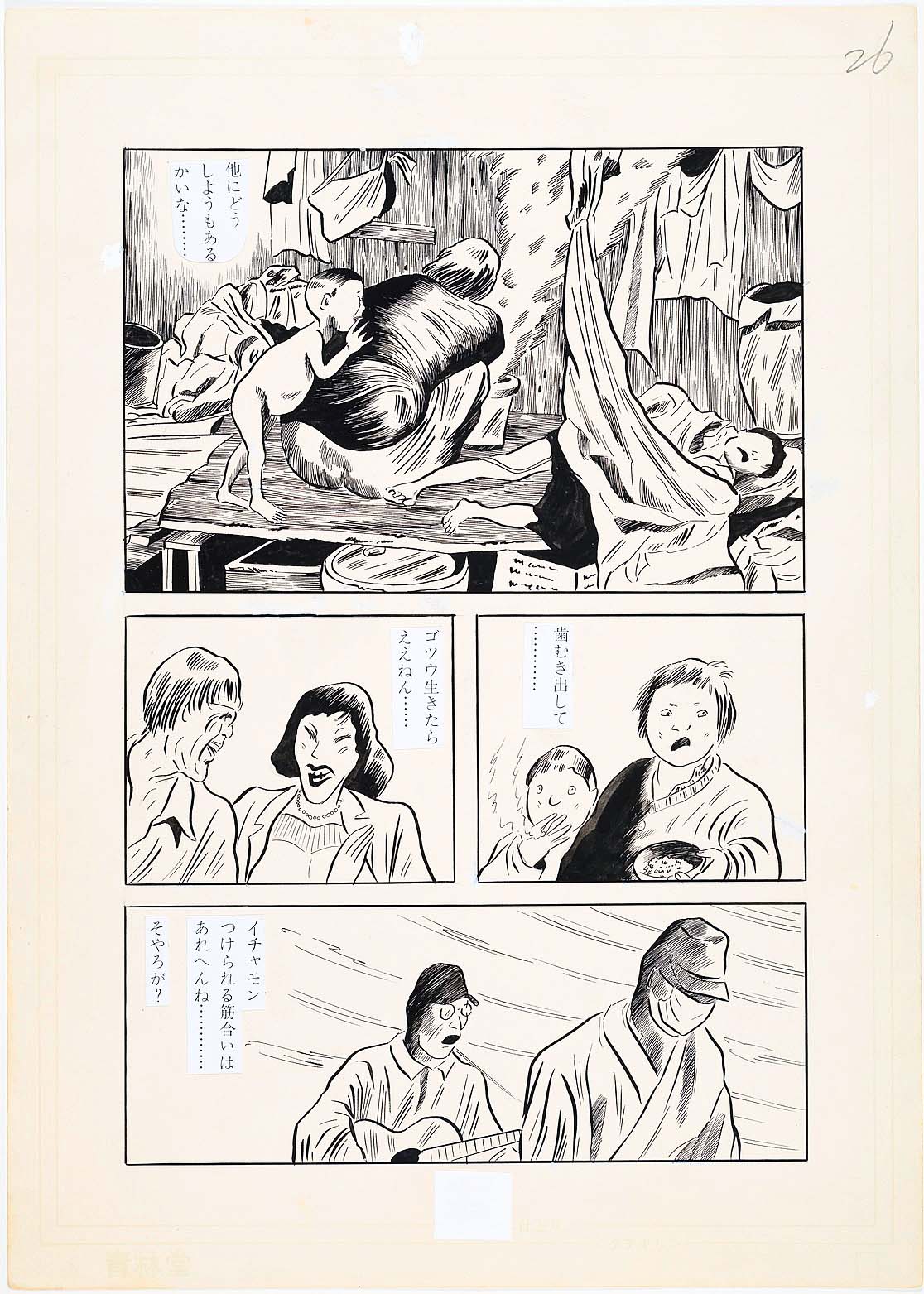

Page 26 of Vagabond Plain (Burai heiya) by Tsuge Tadao (b 1941), Japan, October 1975, hand-drawn comic art (genga); ink on paper. Purchase, 2019 (2019-5-25).

While the museum wanted to share this artwork with its visitors, it was also a personal curiosity for Salel. “I’m intrigued by the way in which the genre of alternative manga and this story by Tsuge in particular challenge many people’s current understanding about the medium of comics. It’s often thought of as a cheap, disposable form of visual entertainment for children, but in fact it has as much potential as any other artform. In this case, we have a story that seriously discusses current social issues. It employs a visual style that reflects a keen understanding of contemporary visual culture, particularly modern photography and iconic images of Western modern art.”

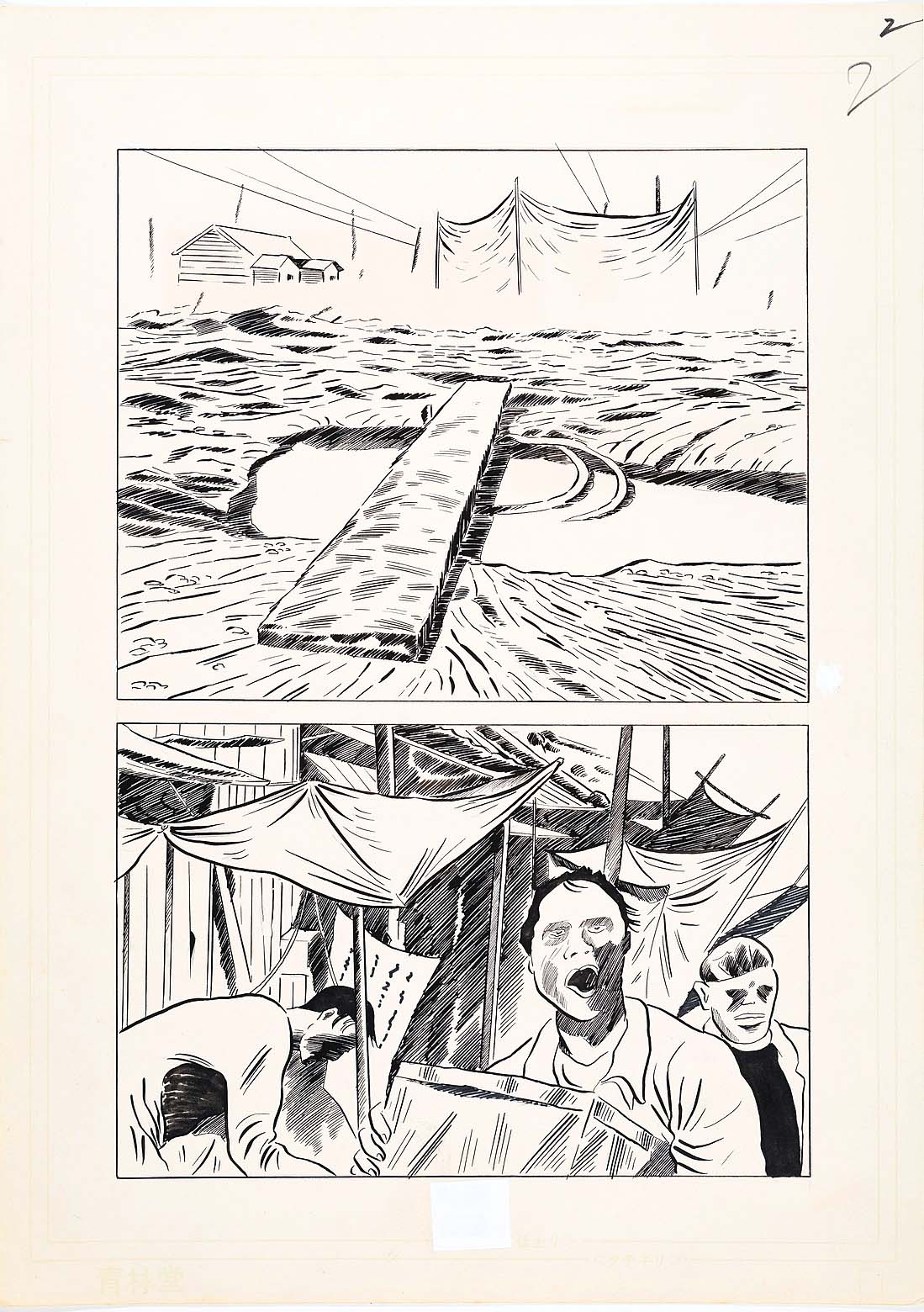

Tsuge, born and raised in Tokyo’s Katsushika Ward — one of several areas of the capital city that were excluded from the country’s economic recovery — wrote Vagabond Plain in 1975. It is a semi-autobiographical story that “focuses on a lower-class neighborhood, making art historical allusions to early European Modernism (the paintings of Vincent van Gogh) and postwar Japanese photography by artists such as Moriyama Daidō (b 1938).”

A description of page 17 of Vagabond Plain, displayed alongside the page, explains the subtle ways in which Tsuge addressed through imagery the struggles that many Japanese people have faced since the Allied Occupation: “Tsuge’s work avoids overtly political commentary. However, considering the overarching theme of his stories — the poverty and social chaos of some urban districts in postwar Japan — the harm caused by the Allied forces during the Pacific War and its mismanaged Occupation is difficult to overlook.”

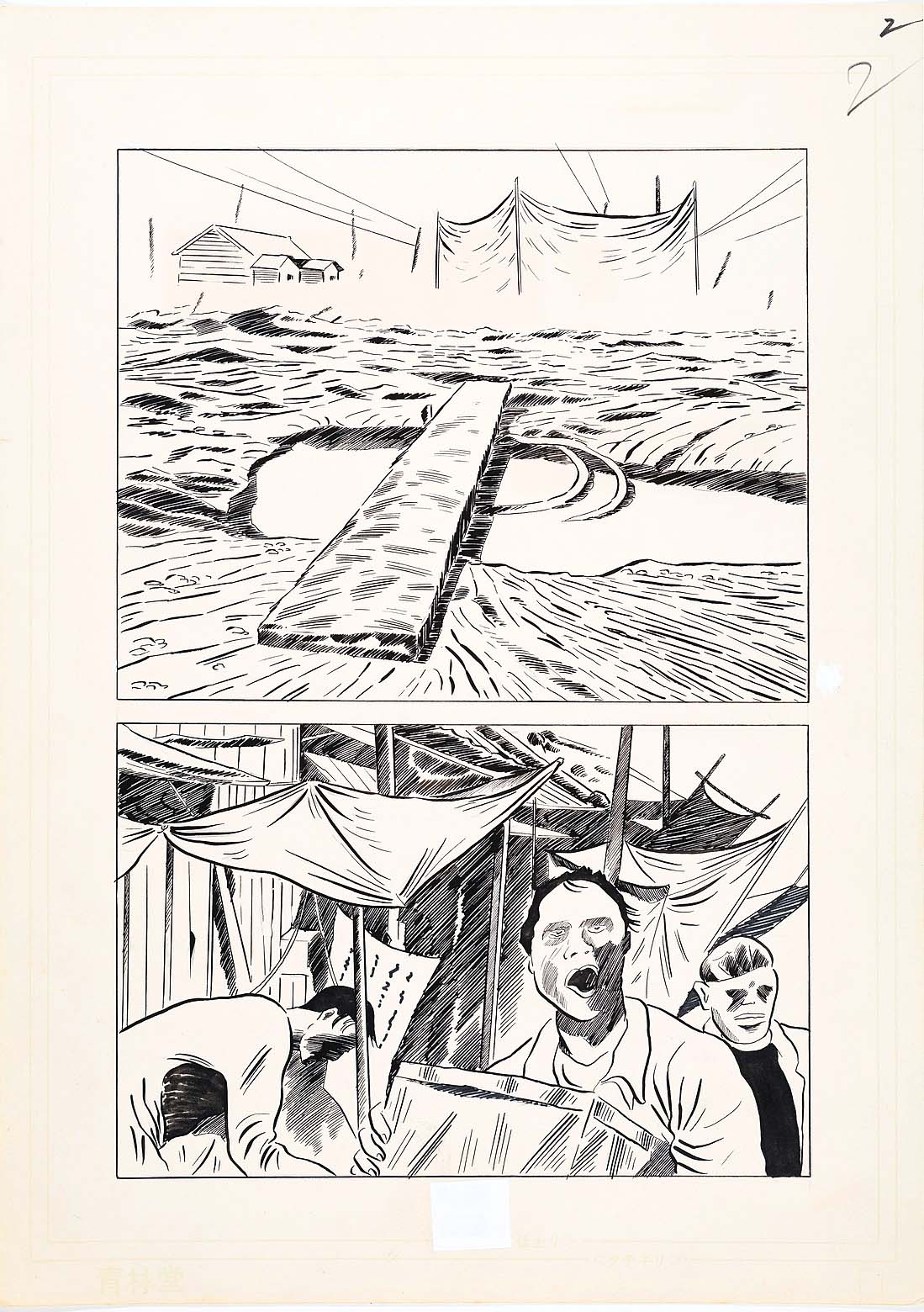

Pages 10-11 of Vagabond Plain (Burai heiya) by Tsuge Tadao (b 1941), Japan, October 1975, hand-drawn comic art (genga); ink on paper. Purchase, 2019 (2019-5-10).

The influence of photography is especially prevalent throughout Vagabond Plain, beginning with the depiction of the American GIs who traverse the shantytown where the story is set. Editorial descriptions accompanying page 22, which depicts a single GI soldier in the background of a busy street, reads, “Tsuge sought inspiration for his imagery in postwar Japanese photography, and in the lower panel on this page, he cunningly depicts one of the soldiers with aviator glasses and a cigarette, satirically referencing a portrait of General Douglas MacArthur — Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces during the postwar Occupation.” This very portrait of MacArthur, taken by Carl Maydans, is displayed next to page 22 as a point of comparison.

Japanese “beggar photographs” (Kojiki Shashin), a style created by Domon Ken (1909-1990), particularly influenced Tsuge’s work in Vagabond Plain. Page 29 offers a harrowing depiction of survivors of the atomic blasts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki whose faces have been distorted. By using crosshatching, Tsuge makes “the figures appear not only alienated from one another but also physically and psychologically wounded.” The work of Ken’s contemporary, Tōmastu Shōmei (1930-2012) is also prevalent here, demonstrated by a comparison to the photographer’s portrait of a nuclear blast survivor, titled “Hibakusha Senji Yamaguchi, Nagasaki” (1962), which is displayed alongside page 29.

Moriyama’s photographs serve as the character-driven and atmospheric inspiration for Vagabond Plain. A label accompanying another page offers insight into the photographer’s work: “During the Pacific War and the subsequent Occupation, Moriyama became fascinated with neon shop-signs, motorized vehicles, Western fashion and the visual chaos of urban entertainment districts. In his photographs, he combined this imagery with a grainy, high-contrast, amateur-like approach to the medium.”

Page 29 of Vagabond Plain (Burai heiya) by Tsuge Tadao (b 1941), Japan, October 1975, hand-drawn comic art (genga); ink on paper. Purchase, 2019 (2019-5-28).

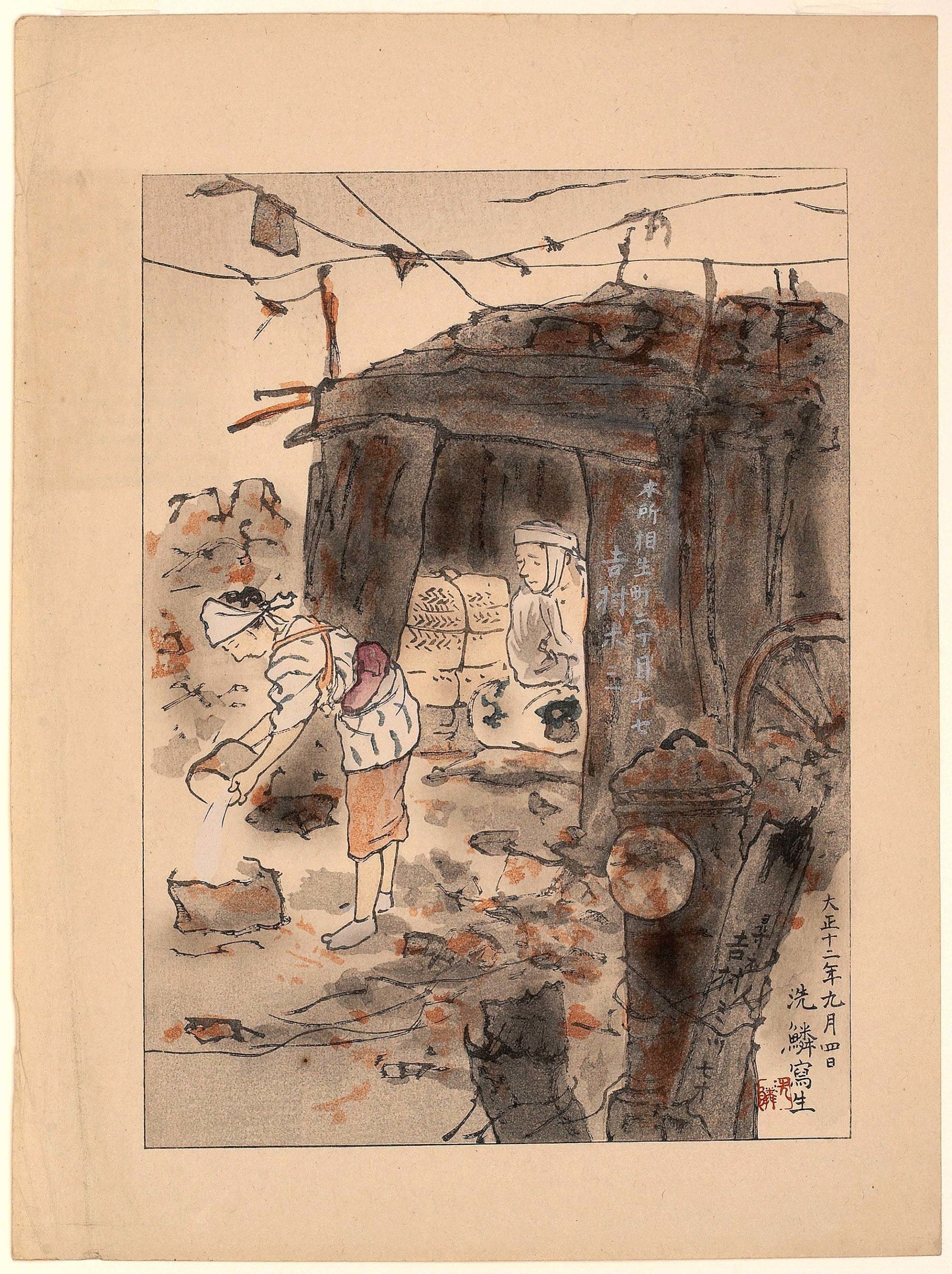

Through the course of the exhibition, viewers come to discover that Vagabond Plain is just one of many examples of Japanese storytelling that offers social commentary on the systemic problems the nation has suffered. The burdens of systemic poverty in Japan have been addressed through art and literature for centuries, said Salel: “In addition to drawing public attention to the artwork of Tsuge Tadao and emphasizing the art historical significance of alternative manga, we emphasize the fact that systemic poverty has been addressed by Japanese artists for centuries. Alongside excerpts from Tsuge’s Vagabond Plain, ‘Drawn from the Street’ includes woodblock prints and woodblock-printed books that depict marginalized members of Japanese society as far back as 1658. I believe that by looking at the history of this problem, we can understand its dynamics a bit better and perhaps find clues that lead to a sustainable solution.”

Socioeconomic challenges have not ceased for Japan since the end of the Allied Occupation; however, despite what the average social media post from a travel blogger or influencer might portray. Changing the Western misconceptions surrounding Japanese poverty and houselessness was another one of the goals Salel hoped to achieve through the exhibition and one of the points of research that was newer to him throughout its development. He observes, “Occasionally, I come across someone who claims that Japan has eradicated the problems of poverty and homelessness entirely. Traveling through Japan, it’s easy to believe this myth. Certainly, the Japanese government provides economic assistance and affordable services to the public in its efforts to minimize severe poverty. However, the nation’s shrinking economy and the discrimination that particular social groups face result in financially distressed communities like the Airin district in Osaka (formerly known as Kamigasaki).”

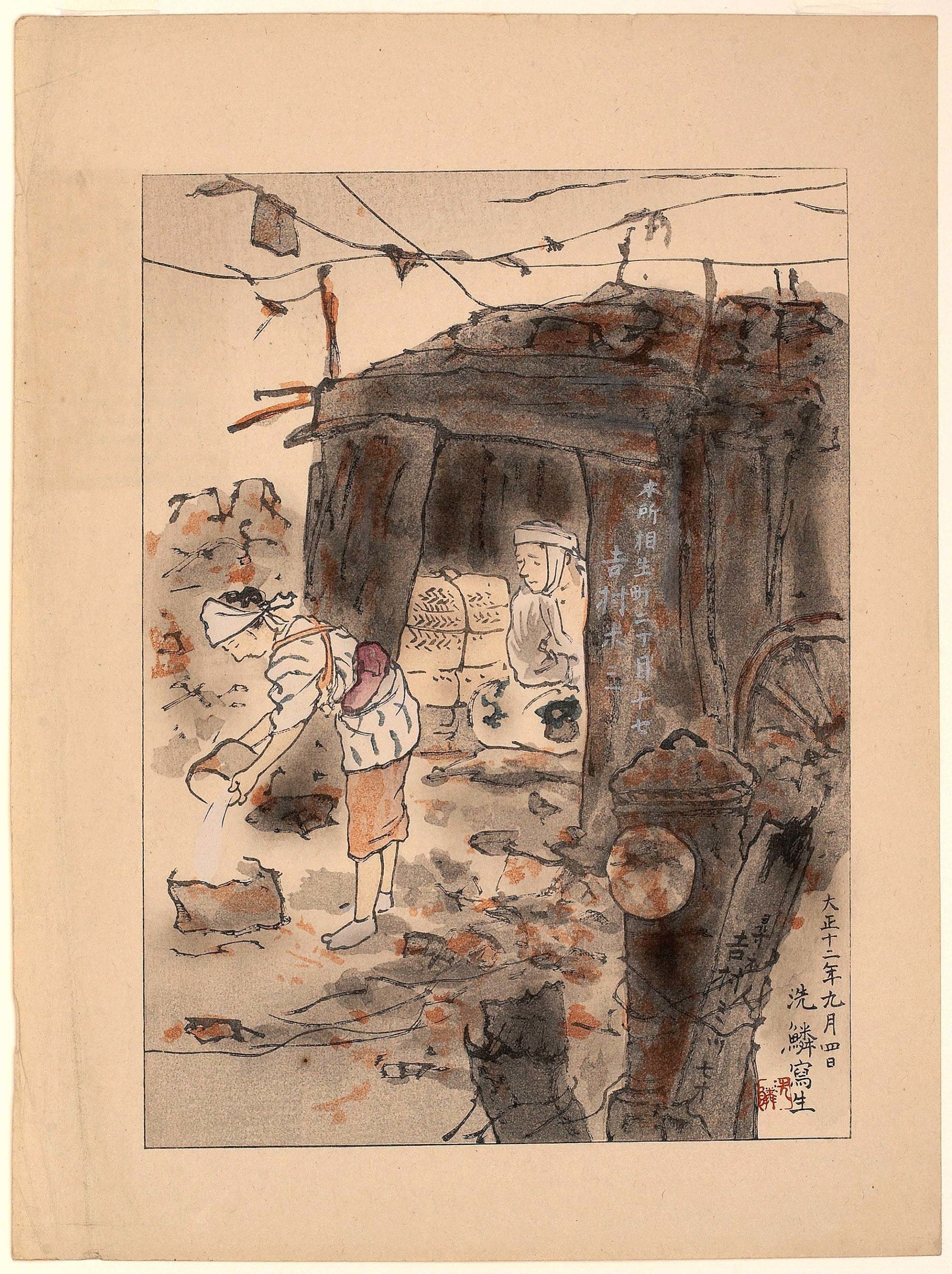

“Temporary Refuge Near Honjo,” from the series “Pictures of the Taisho Earthquake” by Kiriya Senrin (1877-1932), Japan, 1926, woodblock print; ink and color on paper. Gift of Philip H. Roach, Jr, 2010 (25867).

One question that may come to mind when traveling through this exhibition is: Why does Tsuge’s work, and its societal impact, matter to me, as an outsider to this nation and its hardships? Salel is able to bridge this connection, explaining to the hypothetical Western skeptic, “Ever since the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011, which saw people sleeping in tents in city centers across the country, I’ve been thinking about how our social system is failing many of us. The availability of affordable housing was a very important topic in the recent election. In that context, the work of Tsuge Tadao is a good opportunity for all of us to consider the socioeconomic disparity evident in our community and to discuss possible remedies.”

In addition to pointing out universal commonalities, Salel mentioned a few takeaways he hopes that exhibition -goers leave with on their minds. He’d like them “to understand a bit about the popularity of alternative manga in Japan during the decades after the Pacific War. I’d like them to understand how Tsuge, a leading figure in the alternative manga movement, employed a rough style of draftsmanship to create stories about social issues like systemic poverty. Most importantly, I hope they think about cases of systemic poverty in and beyond Honolulu, as well as about how those problems can be most effectively addressed. The first step in solving a social crisis is to encourage public discussion about it — and Tadao Tsuge’s social commentary is a visually engaging, accessible means to that end.”

What’s next for manga at HoMA? Salel shares that he and his colleague, Kiyoe Minami, hope to present “a large-scale exhibition about girls’ comics (shōjo manga) and its contemporary offshoot, women’s comics (josei manga)” in the near future. For now? We’ll have to enjoy all that “Drawn from the Street” has to offer.

“Drawn from the Street: The Politics of Poverty in Postwar Manga” is on view through April 13. The Honolulu Museum of Art is at 900 South Beretania Street. For information, 808-532-8700 or www.honolulumuseum.org.