-1024x742.jpg)

The Dietrich American Foundation assembled a team of scholars to produce In Pursuit of History: A Lifetime Collecting Colonial American Art and Artifacts and its companion exhibition, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from February 1 through June 7. In the museum’s galleries are, center, from left, Dietrich American Foundation curator Deborah Rebuck; foundation president H. Richard Dietrich III; Kathleen A. Foster, Robert L. McNeil Jr. senior curator of American Art and director of the Center for American Art at the PMA; and David L. Barquist, the museum’s H. Richard Dietrich Jr curator of American decorative arts.

By Laura Beach

PHILADELPHIA – A standing-room-only crowd gathered at Sotheby’s on January 31, 1987, to watch auctioneer John L. Marion knock down what would soon be known, at $2.75 million including premium, as the world’s most expensive piece of furniture. Lavishly carved by Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, the hairy-paw foot chair made by Thomas Affleck in 1770 for Philadelphian John Cadwalader went to New York dealer Leigh Keno on behalf of a client.

Keno’s buyer was H. Richard Dietrich Jr (1938-2007), a discreet collector of mainly pre-1820 American fine and decorative arts. All the more remarkable for its candor, the collector’s story is told with affection and insight by his son H. Richard Dietrich III and a team of scholars in In Pursuit of History: A Lifetime Collecting Colonial American Art and Artifacts. In relaying the tale, the ensemble has fashioned the most vivid portrait yet of what some call the Americana movement, that late Twentieth Century moment when scholarship and the marketplace aligned to produce landmark exhibitions, pivotal publications and record prices.

From her office at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), Dietrich’s curator of 37 years and book co-editor Deborah M. Rebuck, whose meticulous recordkeeping and long memory underpin In Pursuit of History, is staging a companion exhibition, “A Collector’s Vision: Highlights from the Dietrich American Foundation,” on view in Gallery 219 of the PMA’s main building from February 1 to June 7. The 55-object show – on which Kathleen Foster, the museum’s Robert L. McNeil Jr, senior curator of American art and director of its Center for American Art, and David Barquist, the PMA’s H. Richard Dietrich Jr curator of American decorative arts, consulted – will open with a vignette evoking the living room at Dietrich Jr’s Chester County estate before moving to focused displays reflecting Chinese influence in the decorative arts, highlights from New York and New England, and masterworks from Philadelphia and nearby Lancaster and Chester Counties. Other groupings will evoke Dietrich Jr’s interest in Pennsylvania German culture, George Washington and whaling artifacts and marine art. Dietrich III and Rebuck anticipate an exhibition of books, manuscripts and documents from the Dietrich collection at the Museum of the American Revolution in the fall of 2021.

Not widely known until now was the breadth of Dietrich Jr’s collecting activity and the degree to which he influenced the market for a half-dozen related specialties. Even PMA curators, with whom Dietrich Jr worked closely from the 1960s on, were startled by his prowess. Writing to the collector in January 1969 regarding his silver holdings, curator Louis C. Madeira IV exclaimed, “I had no idea you had so much and must say you are to be congratulated.”

“I’ve always been interested in family history but it takes a project like this one to focus on it. I’ve included in the book stories my father told but hadn’t written down and culled accounts from newspaper clippings in his files. While we didn’t originally intend a biography, it became clear that the story of the collection is very much about the collector,” Dietrich III said over lunch at Stir, the PMA’s Frank Gehry-designed café.

Loss and opportunity arrived for Dietrich Jr in 1962, when the death of his father prompted the recent Wesleyan University graduate to quit Columbia Business School to assume the presidency of the Dietrich Corporation. His father Henry Richard Dietrich (1908-1962) and uncle Daniel W. Dietrich (1903-1956) were industrial wunderkinds, only 19 and 24 when they financed the $6.5 million purchase of cough drop and candy manufacturer Luden’s.

Dietrich Jr was already collecting when he began his professional life. “He especially loved American history, and not surprisingly when he turned to collecting in his teens his focus was on books, carefully assembling favorite authors and eventually buying first editions of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Melville and others,” his son writes.

Marriage in 1966 to Cordelia Frances Biddle (b 1947) — a union that produced Dietrich III; his sister, Cordelia; and his brother, Christian – and the couple’s renovations to the estate they named Arkadia, a 1721 fieldstone house set on 100 acres of rolling Chester County landscape, provided further inspiration. The property was part of a 187-acre tract Dietrich Jr cobbled together as part of his lifelong interest in land conservation.

His son writes, “This somewhat meandering house with its huge barn and garage space offered Richard a repository and testing ground for his collecting and curatorial methods. He had a knack and a love for reconnecting items from the past. He felt that, in the proper context, objects tell fascinating stories about their time…He also just loved the idea that these reunions of objects may have been hundreds of years in the making, after going their separate ways.”

Easy chair, Thomas Affleck (frame) and Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez (carvers), Philadelphia, 1770. Mahogany, white oak, yellow pine and yellow poplar; new upholstery; height 45 by width 31½ by depth 34 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of H. Richard Dietrich Jr. This easy chair is from a suite of parlor furniture commissioned by John Cadwalader in 1770 and is notable for its elaborate carving.

Dietrich Jr shared a love of history with his older friend and mentor Robert L. McNeil Jr, who left his important collection of American art to the PMA and nudged his protégé onto the PMA’s American Art Advisory Committee in 1969 and onto its board of trustees soon thereafter. He chaired the American Art Advisory Board for 35 years, beginning in 1971.

Dietrich Jr created the Dietrich American Foundation (DAF), a model for collection-based philanthropy that has inspired others, in 1963. His son writes, “He settled on a vision that endures today, and that is one of a collection that supports institutions through loans. The largest beneficiary of this support over the decades and today remains the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The pieces within the collection are made available for loan to institutions around the country. They are also available for scholarly research.” The foundation’s first acquisitions, purchased from Pennsylvania dealer Elinor Gordon, who with her husband, Horace, was one of Dietrich Jr’s longest serving advisors, were a Chinese export porcelain plate and platter from the Society of the Cincinnati service owned by George Washington. The foundation collection now numbers 2,385 objects.

The idea for a book honoring Dietrich Jr arose at a meeting of the DAF board around four years ago. “The collection was 50 and my father had passed a few years before. It seemed like a good time, both for a retrospective look back and as a launching point for the future,” Dietrich III says.

With his essay on the foundation’s collection of books, manuscripts and maps, written with Philip C. Mead, the consummate bookman William S. Reese (1955-2018) created a template used by the volume’s other contributors. Rebuck observes, “Bill came up with the idea of tracking Richard’s interest in objects by when and how he acquired them.” As the contributors compared chronologies across disciplines, clues to Dietrich Jr’s evolving enthusiasms emerged.

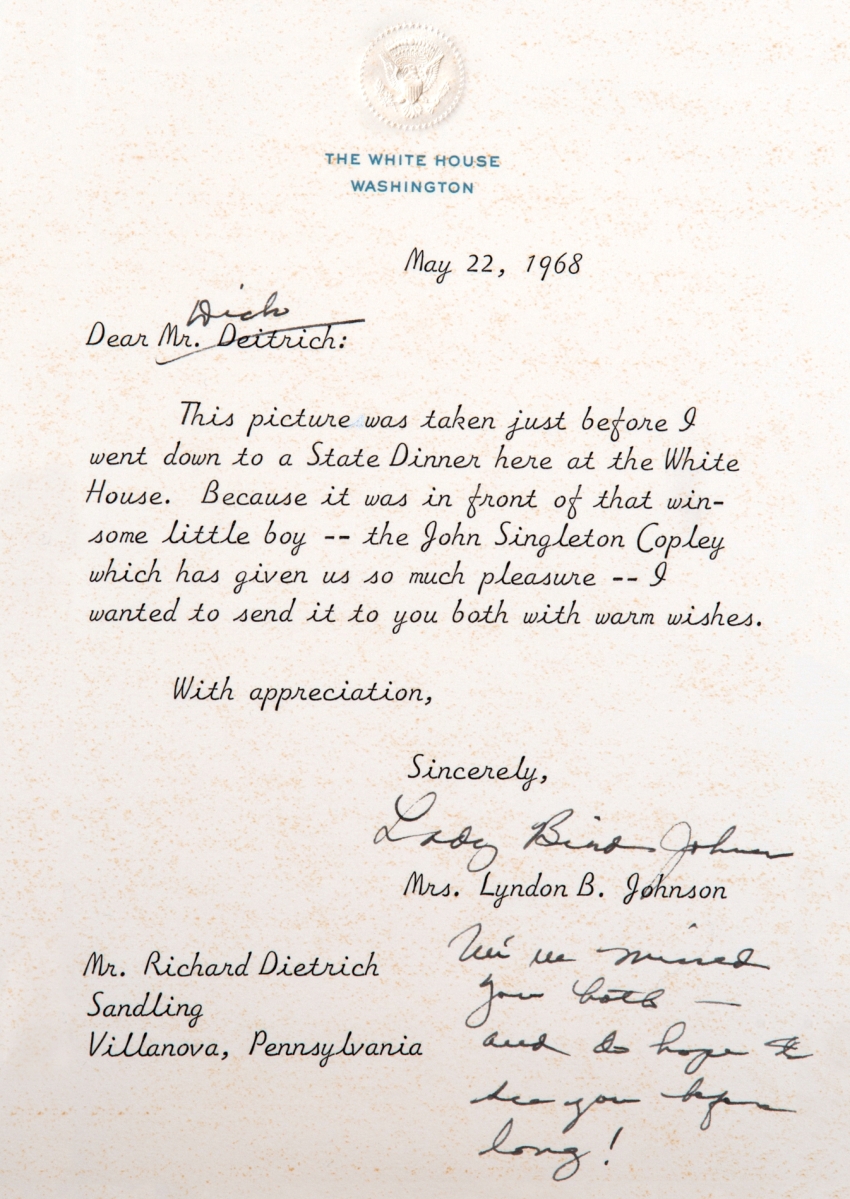

“By any estimation, Dietrich assembled one of the greatest collections of Americana books and manuscripts brought together in the second half of the Twentieth Century. He pursued material with vigor and passion,” Reese and Mead, chief historian and director of curatorial affairs at Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution, write. Dietrich’s pursuit began in 1963 with his acquisition of a 1776 Washington letter, escalated with purchases from collections formed by Henry Flynt and Thomas Streeter, and reached a pinnacle in 1994 when he landed the Eliot Indian Bible at Sotheby’s.

We think of the 1980s as the beginning of the bull market in Americana. In fact, as Yale professor Edward S. Cooke Jr illustrates in his essay on the evolution of the DAF furniture collection, the 1980s were the culmination of much that had been set in motion in the 1950s and 1960s. Dietrich Jr, Metropolitan Museum curator emeritus Morrison H. Heckscher notes, “was lucky to begin in the 1960s when so much material was on the market at reasonable prices. He was busiest with acquisitions early on, but he continued to buy, and in the case of paintings and furniture quite often sell, throughout his lifetime.”

H. Richard Dietrich III in an undated photograph. His love of the sea and maritime history resulted in an exceptional collection of marine, China trade and whaling art and artifacts.

Dietrich Jr’s first major furniture acquisition, from dealer John Walton in 1963, was an elegant bombé desk with a carved shell pendant on its skirt. Thanks to recent research by Kemble Widmer and Joyce King, we now know it to have been made circa 1765-75 by Salem, Mass., cabinetmaker Nathaniel Gould. The collector made two key additions of Boston furniture in the late 1970s, a serpentine bombé chest and a japanned high chest. Working closely with Keno between 1987 and 1996, he acquired roughly 20 important pieces of furniture, among them a Connecticut painted joined chest with drawer that had been in the 1982 exhibition “New England Begins: The Seventeenth Century” and in 1987, a Philadelphia piecrust tea table and a rare marble slab table once owned by the Penn family. In the last decade of his life, perhaps prompted by the 1999 PMA exhibition “Worldly Goods,” Dietrich Jr focused on early Philadelphia and Chester County pieces, works that paired well with his collection of early Pennsylvania German fracktur and furniture, described in a chapter by Lisa Minardi.

“I’d take the Benjamin Wynkoop (1675-1751) brandywine bowl,” Barquist, a silver authority and catalog essayist, responds unhesitatingly when asked which Dietrich treasure most appeals to him. The circa 1698-1710 relic of Dutch New York is from the DAF’s small collection of mostly pre-1800 silver, much of it Philadelphia made. Dietrich Jr bought his first piece of silver, a War of 1812 beaker accompanied by a logbook kept aboard the USS Peacock, in 1967 and proceeded just two years later to win a sauceboat by Paul Revere for a record price. He set another auction record with his acquisition of the Wynkoop bowl in 1981. Barquist concludes, “Over time Dietrich’s interests shifted, from later Eighteenth Century objects in the Neoclassical style to earlier Eighteenth Century examples, but he never wavered in his quest for silver of exceptional beauty and historical importance.”

Dietrich Jr, who loved paintings as evocative accompaniments to furniture and objects, acquired only about 50 oils and 130 watercolors and drawings still in the foundation’s collection. Roughly 25 percent of his flat art documented sea battles. Foster writes that his finest marine painting was Ambroise Louis Garneray’s (1783-1857) War of 1812 commemorative “Engagement of the Constitution and the Guerriere.”

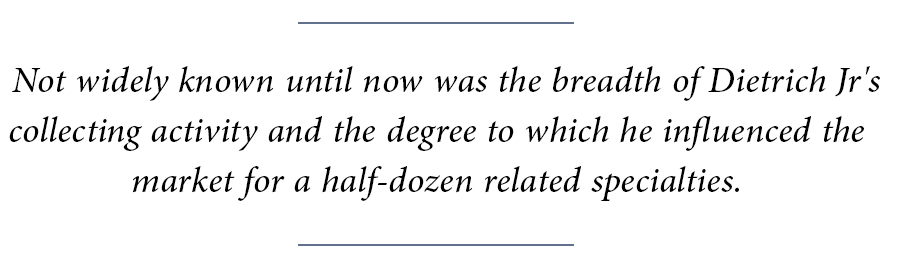

The collector’s choices were often exceptional, as demonstrated by his 1964 purchase of John Singleton Copley’s (1738-1815) 1766 portrait of the 6-year-old John Bee Holmes with his pet squirrel. After lending the painting to the White House, the collector installed it in Arkadia’s living room above his Gould desk, on which he displayed silver by Paul Revere. Nearby was Revere’s 1770 engraving, “The Bloody Massacre.” Foster observes, “…the painting reads as a witness to their interwoven history, less about Copley’s individual story as an artist, and more about the human context of the ensemble.” The DAF’s best painting, says Foster, is Copley’s 1767 portrait of Josiah Quincy, purchased in 1971.

The foundation’s first pieces of export porcelain, from Washington’s Society of the Cincinnati service, “connected decorative art to Richard’s keen interest in Washington. He ended up purchasing many George Washington letters and books owned by the first president, as well as paintings of Washington, including a James Peale miniature on ivory,” Rebuck writes. Much of the porcelain he bought, especially in later years, “came from services made for specific families or ones with strong American connections and that had passed down through families.”

Dietrich Jr’s acquisition of a house on Fishers Island, N.Y., in 1969 coincided with his growing interest in marine art and artifacts, particularly whale-trade objects, an area evaluated by Michael P. Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. After storming a Richard Bourne auction in 1966, Dietrich Jr proceeded to buy, among many other trophies, two whale’s teeth engraved by Frederick Myrick onboard the ship Susan of Nantucket in the 1820s. Today they are on loan to Mystic Seaport.

Dietrich Jr’s loans to the PMA began in 1966. Though dozens of institutions from Maine to California currently benefit from the foundation’s largesse, it is with the PMA that the DAF works most closely. “From very early on Richard’s loans to the museum were key,” says Foster, mentioning John Singleton Copley as one artist not represented in the PMA’s holdings before Dietrich Jr filled the void.

The record sale of the Cadwalader easy chair a little more than two centuries after it was made brought the reticent collector unsought attention while also stimulating new research on and escalating prices for American decorative arts. Five years before his death, Dietrich Jr donated the chair to the PMA in honor of the museum’s 125th anniversary. It resides there amid other items from a once great suite, a fitting symbol of a collector and the era he did much to shape.

In Pursuit of History: A Lifetime Collecting Colonial American Art and Artifacts will be highlighted at Sotheby’s Americana Symposium on January 21. Dietrich III is speaking as part of the day-long program featuring talks by more than a dozen experts. He will also participate in a book signing at Christie’s January 22 preview reception in conjunction with the Wunsch Award presentation. Additional programs, including private tours of the exhibition led by Rebuck, are anticipated.

Published by the Dietrich American Foundation in association with the Philadelphia Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press, In Pursuit of History: A Lifetime Collecting Colonial American Art and Artifacts is edited by H. Richard Dietrich III and Deborah M. Rebuck. With photographs by Gavin Ashworth and Cliff Sahlin, the hardcover edition sells for $50.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is at 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For information, www.philamuseum.org or 215-763-8100.

Photographs courtesy Dietrich American Foundation unless otherwise noted.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)