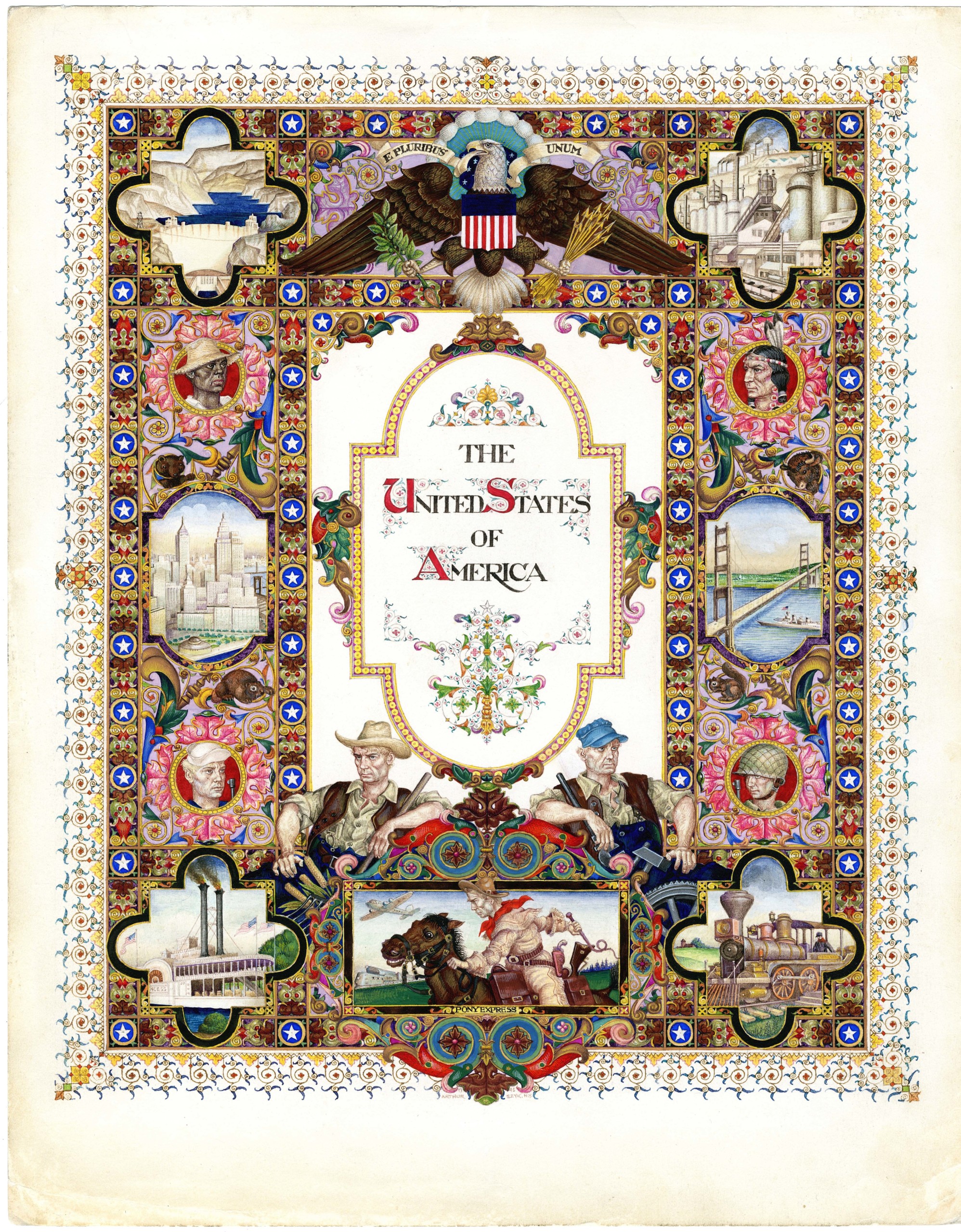

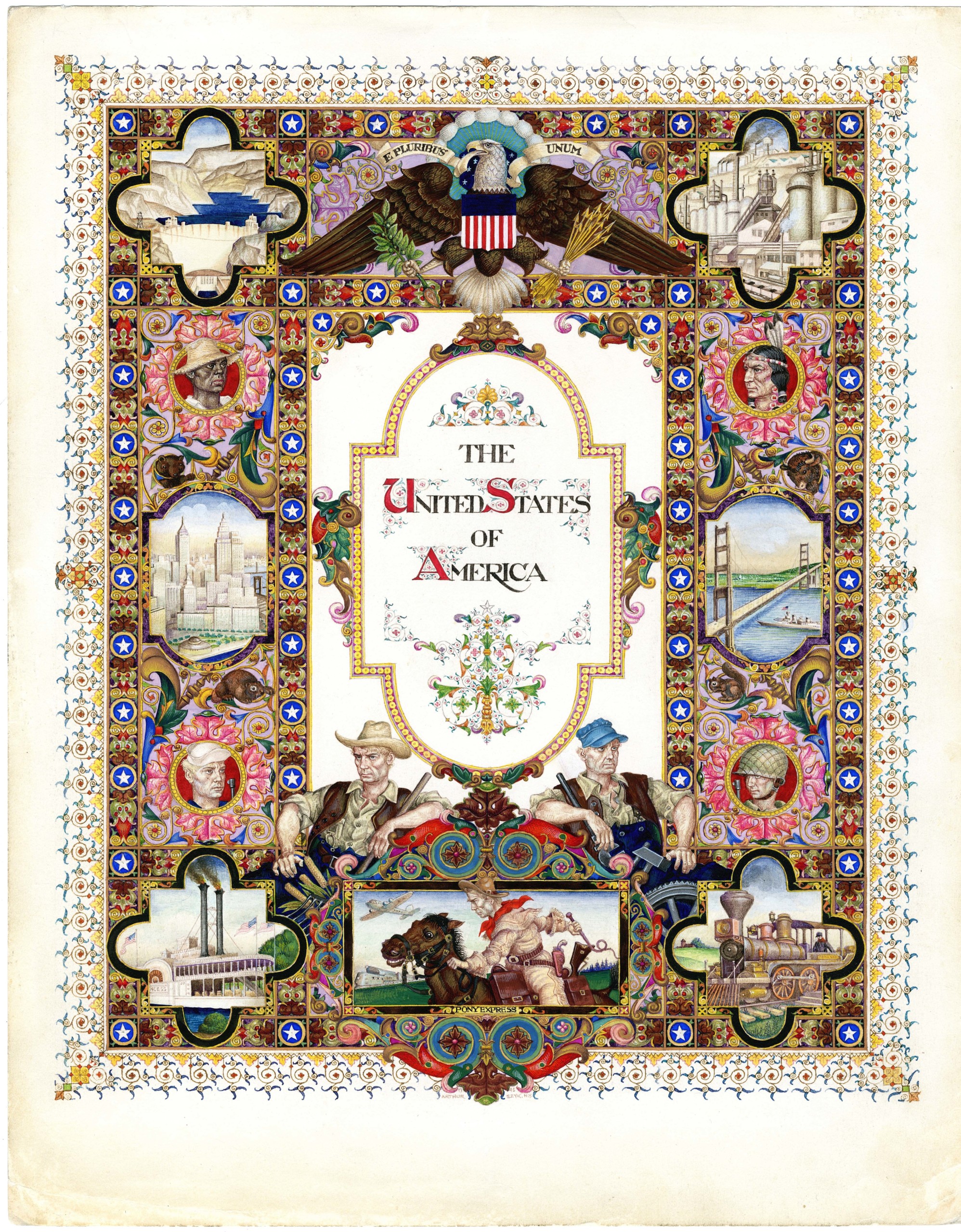

“The United States of America” (Heritage of the Nations series), New York, 1945, watercolor and gouache, pen and ink and pencil on board. Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection.

By Kristin Nord

All images courtesy the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art & Life, University of California, Berkeley.

FAIRFIELD, CONN. — What can be said of the meteor that was Arthur Szyk? He was a proud Jewish Pole, an American and a Zionist. His art can require both a magnifying glass and the wherewithal to grasp his biblical and historical references. And his extensive body of work ranges from brilliant, illuminated manuscripts and book illustrations to explosive political cartoons.

According to Ori Z. Soltes, who teaches at the Center for Jewish Civilization at Georgetown University, Szyk was, without a doubt, “one of the more extraordinary individuals to arrive on these shores during the catastrophe of the Second World War and the Holocaust — and to turn his hatred of injustice into brilliant visual expression.” His art synthesized “the most extraordinary of medieval and renaissance illumination concepts with a modernist sensibility,” he adds.

Arthur Szyk’s miniatures are breathtaking. But so, too, are his political cartoons. “In Real Times, Arthur Szyk: Artist and Soldier for Human Rights,” on view through December 16 in the Bellarmine Hall Galleries and Walsh Gallery at Fairfield University Art Museum, is an exhibition for our times.

“The response has been tremendous. People cannot get over the detail in his work, and the power of his cartoons,” Carey Mack Weber, the museum’s Frank and Clara Meditz executive director, said recently. “We have had more than 2,000 in-person visitors to the galleries and programs over the past three weeks and over 15,000 virtual visitors to view the video tour and the opening night lecture.” Organized by the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at UC Berkeley and curated by the Magnes’ curator Francesco Spagnolo, the exhibition has been enriched by new scholarship and efforts by established and emerging Szyk scholars.

“Madness, New York,” 1941, watercolor, gouache, ink and graphite on paper. Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection.

Syzk was born in 1894 in Lodz, Poland, in what was one of Europe’s largest Jewish population centers. Lodz was a major textile manufacturing city, and his father ran one of its factories. Szyk showed an early aptitude in art, and some have pointed to his easy access to the decorative pattern books of the trade as a significant early influence.

At the same time, he was no stranger to violence: when he was still a young boy, he saw his father blinded by acid during a workers’ strike. He was also aware of increasing acts of antisemitism. The ground was shifting, and yet people had not fully awakened to the dangers posed by Germany, Italy and Japan.

Syzk was just 15 when his father sent him to Paris to pursue art studies at the Academie Julian. There, he learned how to make illuminated texts and began creating miniatures that referenced art from the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. One of the great pleasures of the exhibition is the opportunity to linger in front of individual works and consider their intricate elements. They were created with only cursory preparative sketches.

“Almost all his artworks were designed to be reproduced by the printing press,” the art historian James Kettlewell notes, “but in a medieval manner, with the artist seated at a table, employing the opaque watercolor (gouache) techniques of manuscript illumination. It is not a coincidence that this technique was similar to that of a sofer, a calligrapher of sacred Jewish texts,” he adds.

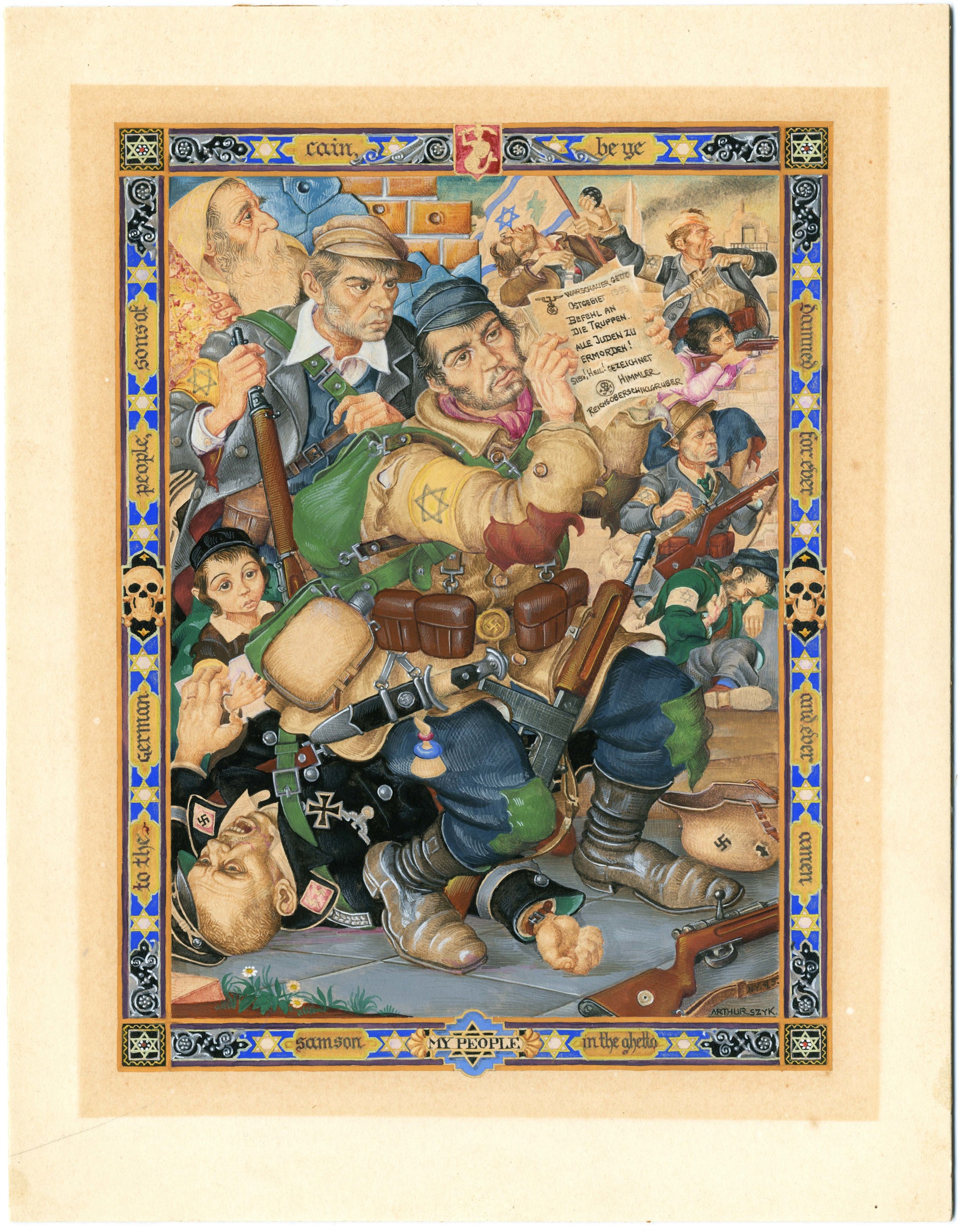

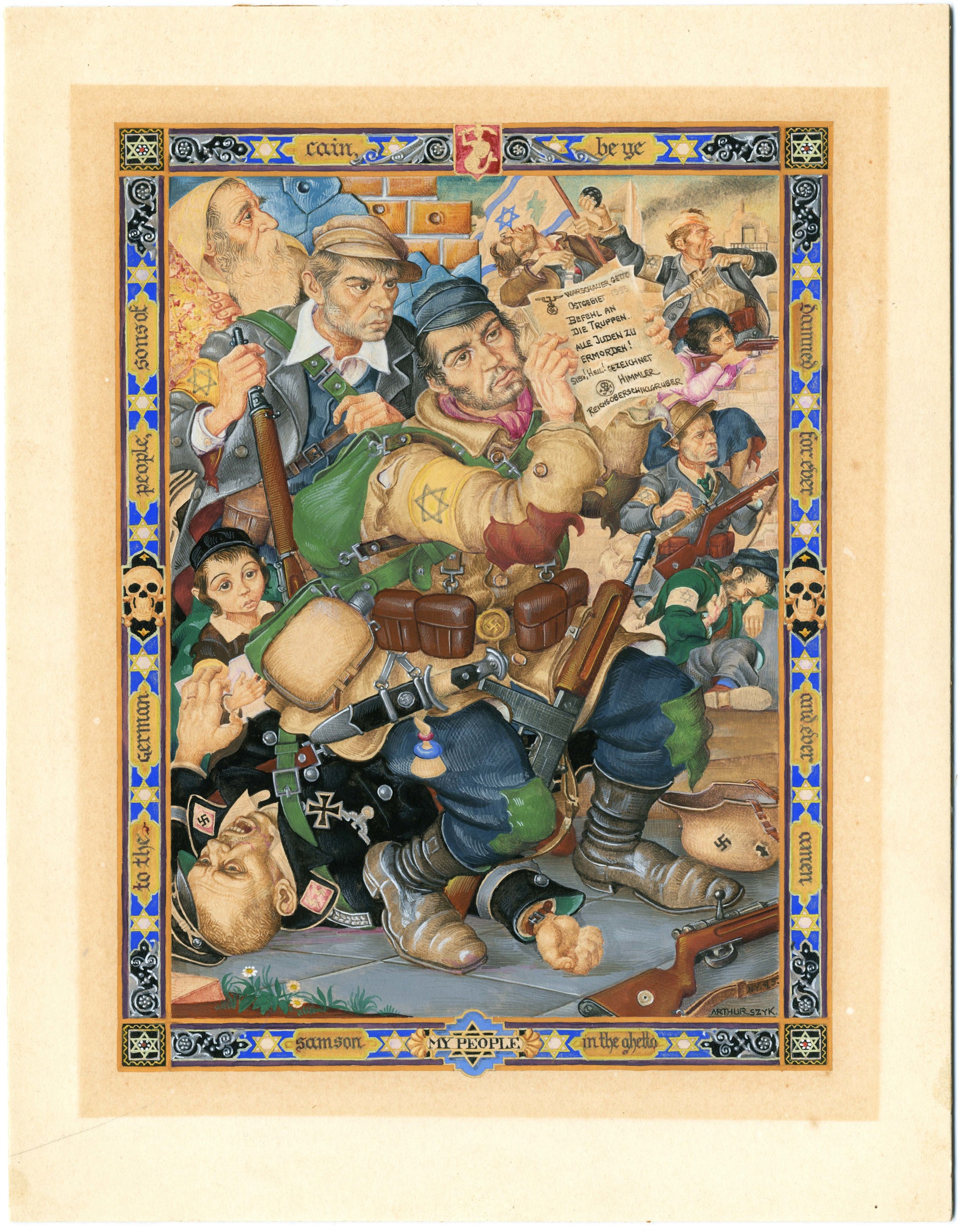

“My People, Samson in the Ghetto (The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto),” New York, 1945, watercolor, gouache, ink and graphite on board. Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection.

Szyk worked on 48 paintings of the Haggadah — the story of the Israelites leaving Egypt, traditionally retold at Passover — in the 1930s, and they were gathered into book form and published in London in 1940 to tremendous acclaim. At the time, it was the most expensive new book in the world, with limited-edition copies selling for $520 apiece (or the equivalent of nearly $11,000 today). The Times of London proclaimed it “worthy to be placed among the most beautiful of books that the hand of man has ever produced.”

But just a year earlier, Germany had invaded Poland and the rumors of Hitler’s assault had become all too real. Szyk initially felt duty-bound to warn his adopted country — he’d immigrated to America in 1940 — of the dire and imminent threat posed by what is now referred to as “The Evil Axis.” With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Szyk’s art took on ever-greater urgency. He was bearing witness, and calling for action, in covers like the one that appeared in the January 17, 1942, issue of Collier’s magazine. Titled “Madness,” Szyk forewarned, “All hope abandoned ye who enter here,” as he stations Hitler and Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler and Joseph Goebbels around a globe that is pierced by swastikas.

Throughout the 1940s, Szyk self-identified as a soldier in art and became the country’s leading anti-Nazi artist. Some 1,000 of his political cartoons were published and they showed up seemingly everywhere: on the covers of major magazines, as posters on the walls of 500 USO recreation centers, as postcards, in production campaigns for US Steel. GIs purportedly favored his cartoons over pin-ups of Betty Grable.

Szyk’s cartoons also appeared in the Polish Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York and in some 25 exhibitions. After encountering Szyk’s work at Seligman Galleries in New York City, Eleanor Roosevelt was prompted to write, “In its way it fights the war against Hitlerism as truly as any of us who cannot actually be on the fighting fronts today. This war is personal for Mr Syzk. I do not think he will lose it.”

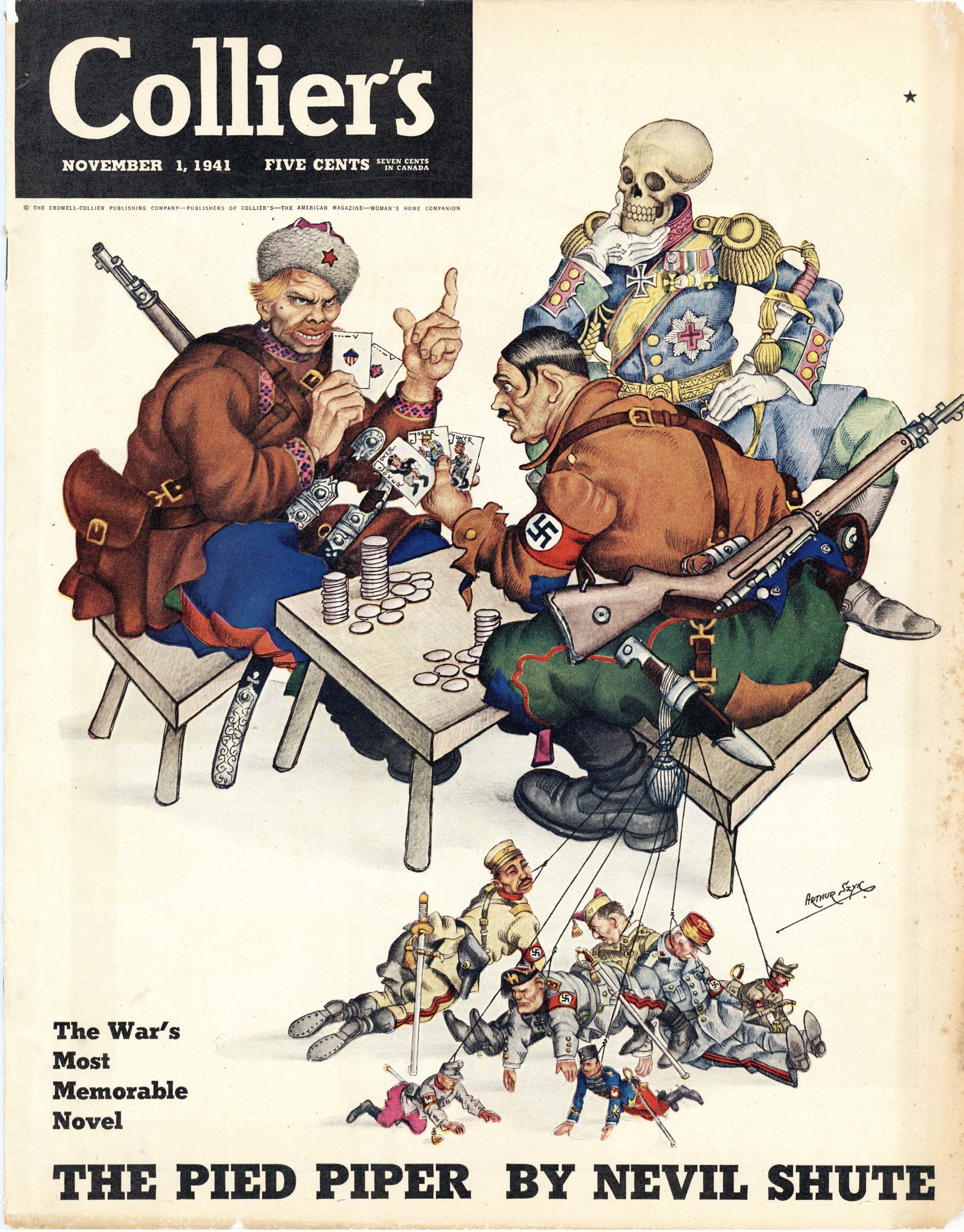

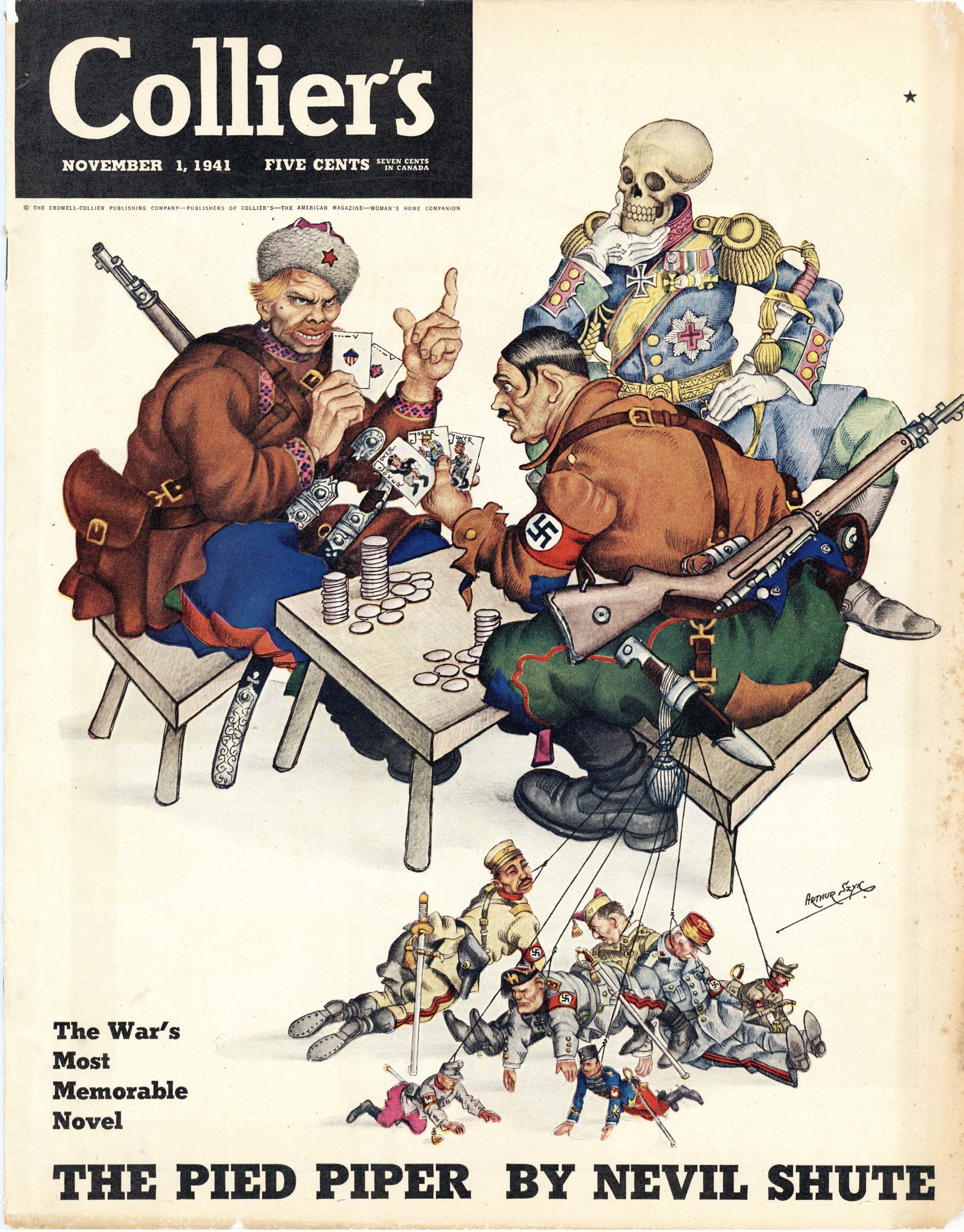

The Silent Partner. “In this game, Adolph [sic], Two Aces is More Than Three Kings,” Collier’s (front cover) New York, November 1, 1941, offset lithograph. Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection.

Steven Luckert, PhD, longtime senior program curator at the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, says Szyk wore the mantle of propagandist proudly. “While such an epithet seems anathema to contemporary audiences, for Szyk it meant he consciously created artwork that carried a message. His causes varied, from forging a strong heroic self-image of the Jews to negating antisemitic stereotypes to calling out American racism against Blacks when he encountered them.” Then, as now, there was no shortage of material.

Szyk took care to incorporate the comic, the vain and the soon-to-be vanquished. “Such variety is purposeful on the part of the cartoonist since audiences not only had to fear the enemy, they had to believe he was not invincible,” writes Luckert, who has overseen permanent and special exhibitions at the museum writes in the exhibition’s accompanying catalog. “Laughter and ridicule served as the cartoonist’s weapon to mock one’s foe by exposing his weaknesses.”

Hitler appears as the anti-Christ in any number of Szyk cartoons: holding his bible, Mein Kempf, aloft, or marching forward under the symbol of the Nazi swastika. He rants and raves and stamps on skulls labeled “Jude.”

It’s impossible to grasp the power of this work — whether “Madness” or “The Silent Partner, Don’t Believe a Word of It” or “Ink and Blood” or “Parade of Mighty Warriors!” — without seeing it in person. Szyk’s corpulent villains will haunt a viewer long after a visit to the art museum’s Bellarmine Galleries. Interactive features of the show, and video of the artist, help to fill in Szyk’s story and provide further historical context.

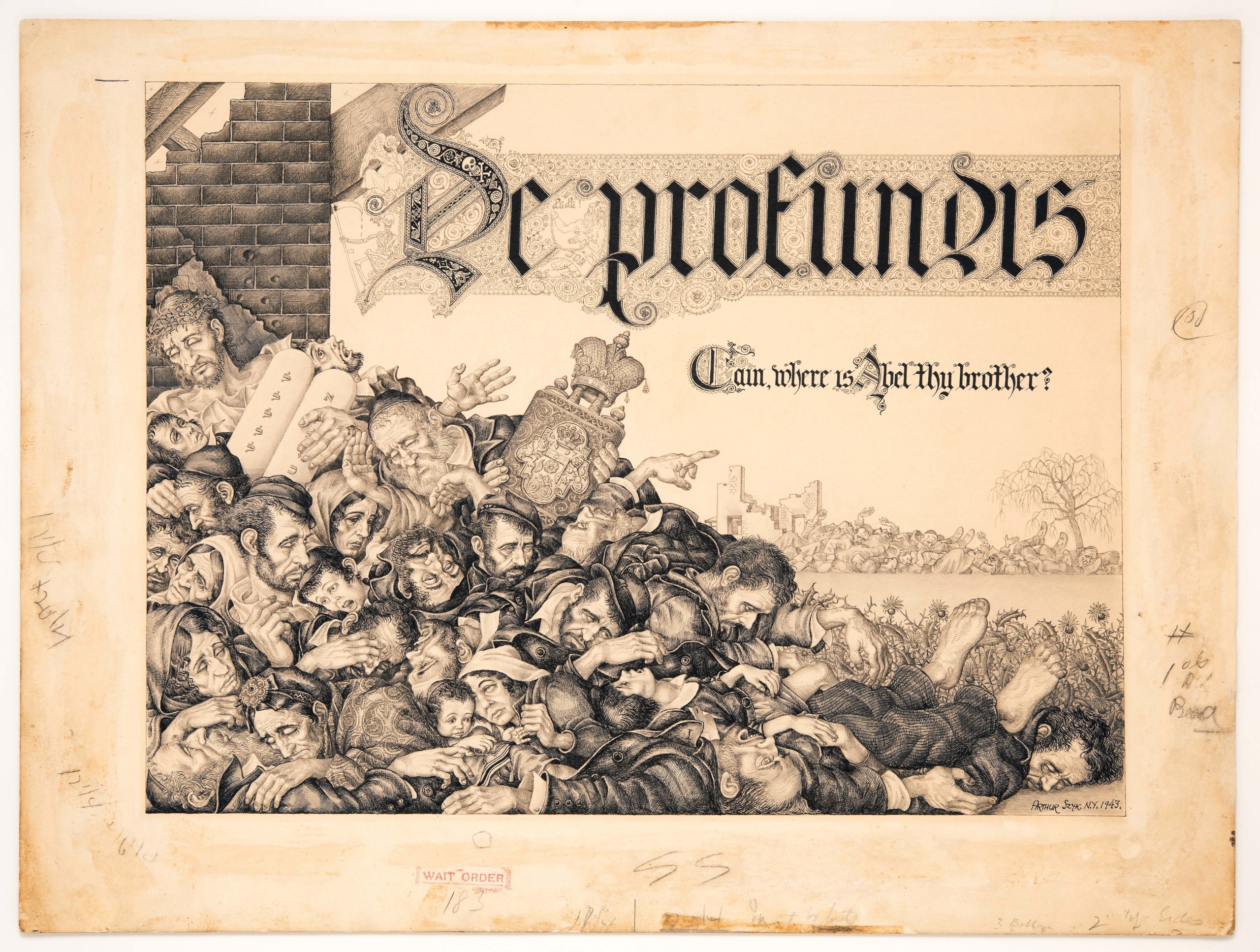

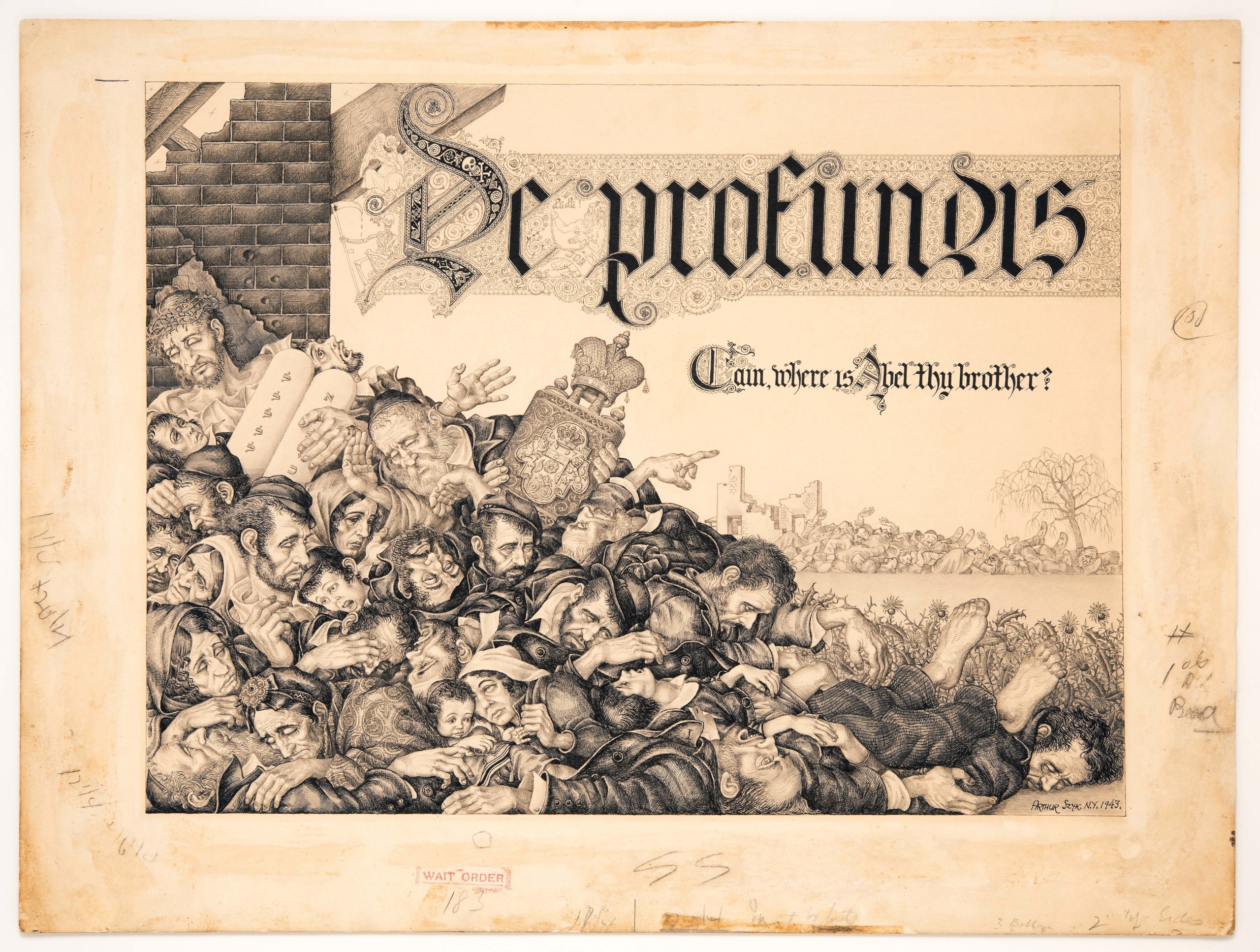

“De Profundis. Cain, Where is Abel Thy Brother?,” 1943, ink and graphite on board. Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection.

In “De Profundis: Cain, where is Abel! Thy Brother?,” which appeared in The Chicago Sun-Times in February 1943, Szyk invokes Psalm 130 to issue this plaintive cry: “Out of the depths they speak…2,000,000 sensitive beings tortured, starved, butchered, in an orgy of hate reaped by Hitler but sown in the very soil of Christian civilization, sown in the texts of intolerance.”

“And We are Running Short of Jews,” the cover illustration of the July 20, 1943, issue of Collier’s, conjures a scene in which Hitler is reviewing the latest Gestapo reports. “2,000 Jews Executed-Heil Hitler,” Hitler announces with satisfaction. An updated death toll would include Szyk’s mother and brother, who were rounded up in the Lodz ghetto in 1943 and 1944 and believed to have perished en route to the Chelmno Killing Center.

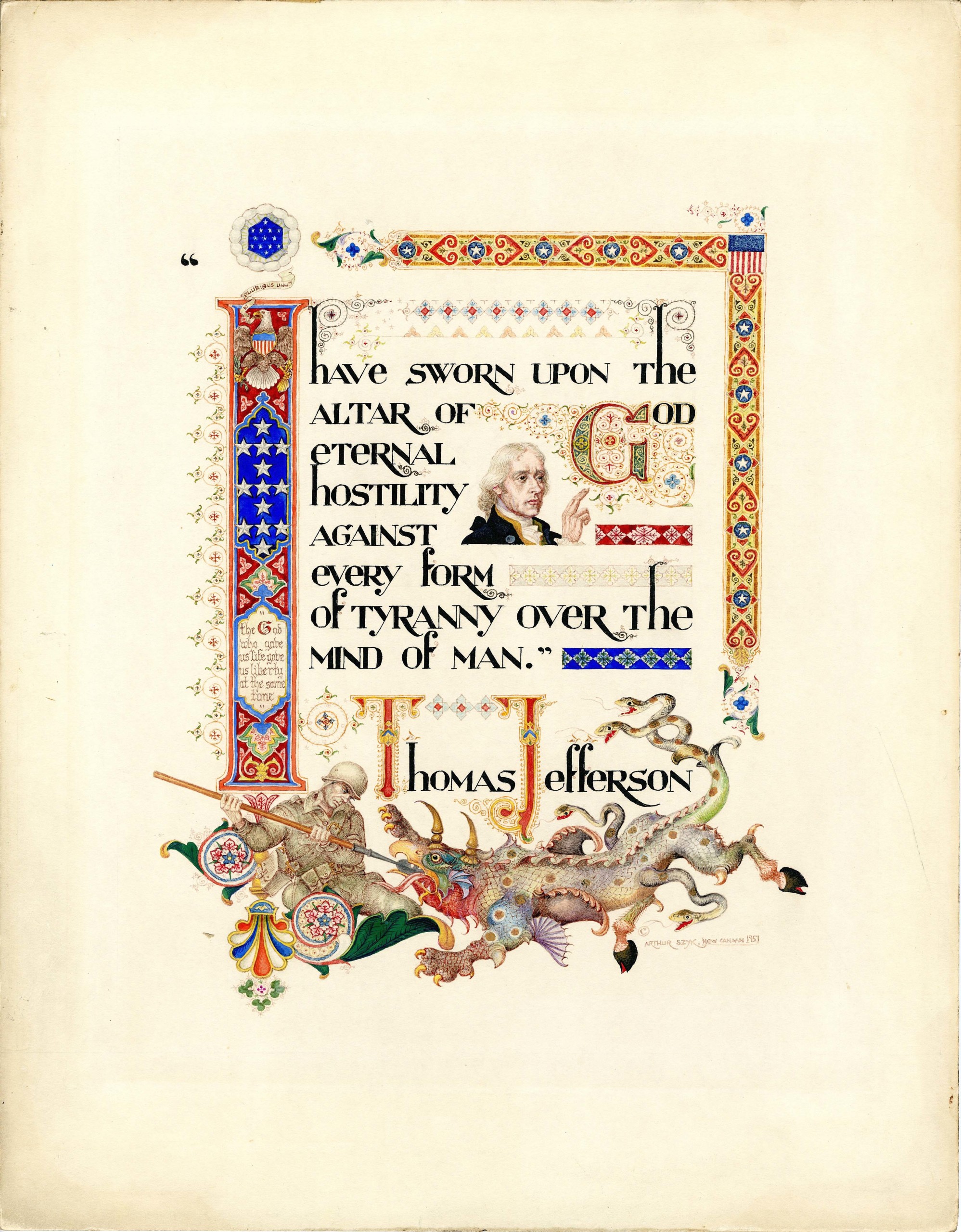

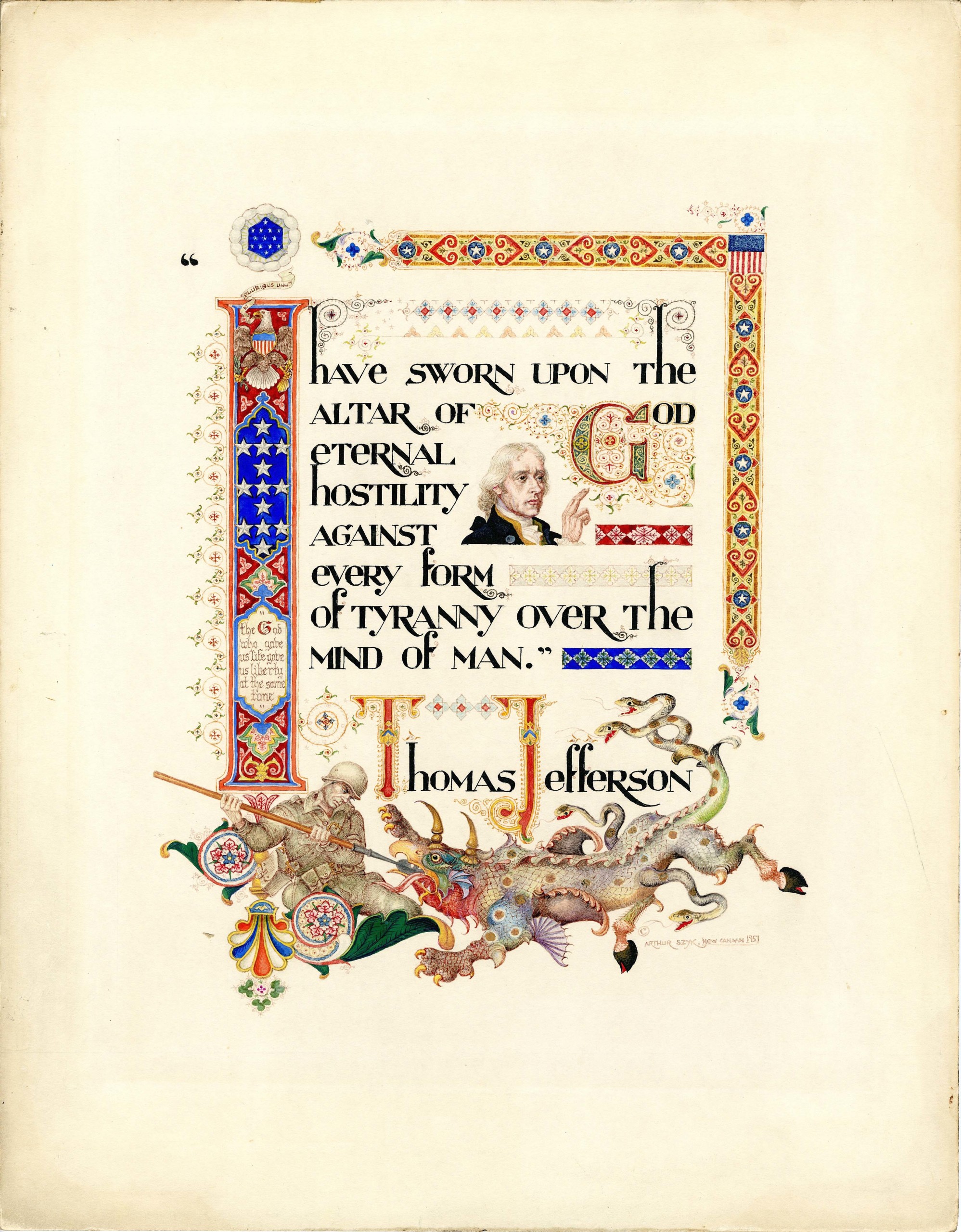

Throughout these dark and terrifying times, the artist persevered. Living out the last years of his life in New Canaan, Conn., where he died in 1951, he believed in America despite its faults, and he championed the ideals of its founders. He continued to illustrate books — including Omar Khayyam’s The Rubaiyat and Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales. He produced his paean to America in his Four Freedoms, inspired by FDR’s 1941 State of the Union address.

“Thomas Jefferson’s Oath,” 1951, watercolor, gouache, ink and colored pencil on board. Taube Family Arthur Szyk Collection.

Philip I. Eliasoph, Fairfield University’s professor of art history and the visual arts and the exhibition’s coordinator, has worked assiduously with Weber to mount not only the opening symposium but a semester’s worth of lectures that can be streamed at home. Eliasoph has also overseen the catalog, Arthur Szyk: Art-Propaganda-Memory, with new scholarship that enriches the conversation. Tragically, Eliasoph notes, the threats to humanity that Syzk perceived 70 years ago remains terribly real today.

Whether it is Putin justifying mass killings and kidnappings in Ukraine as a noble effort to restore the russkiy mir, or the catastrophic war that has been unfolding between Israel and Hamas, pundits of the fourth estate are writing about the emergence of a new world order. The world has not rid itself of dictators yet, nor escaped the devastating costs of war.

Syzk had been overjoyed when Israel came into existence. Of himself and his work, he said, simply, “I am but a Jew praying in art.” One can’t help but wonder what the illuminator would say to us now.

The Bellarmine Hall Galleries at the Fairfield University Art Museum is at 1073 North Benson Road. For information, 203-254-4046 or www.fairfield.edu/museum.