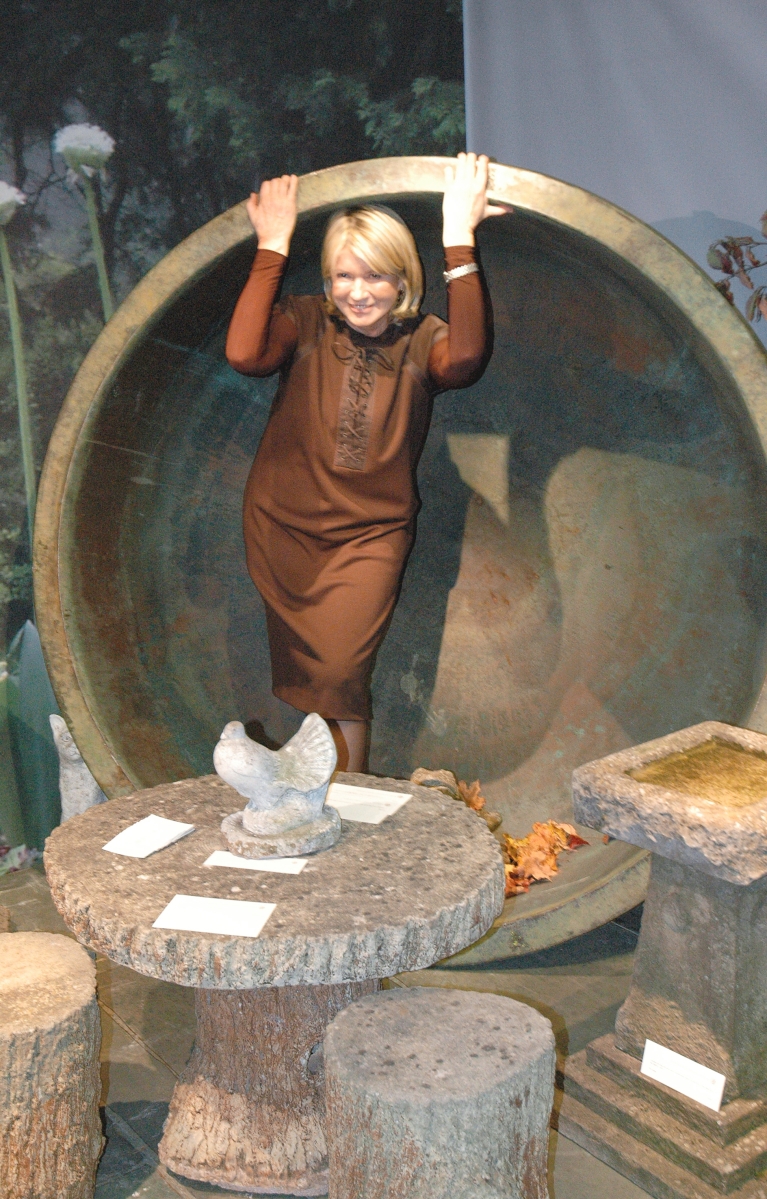

The Winter Show’s executive director, Helen Allen, introduces the press corps to the 2020 loan show, curated by designer Peter Marino and former Metropolitan Museum of Art chairman Philippe de Montebello. The loan show promotes American institutions and the fair’s American identity, while also underscoring the connection between private collecting and public patronage. Photo courtesy Winter Show.

By Laura Beach

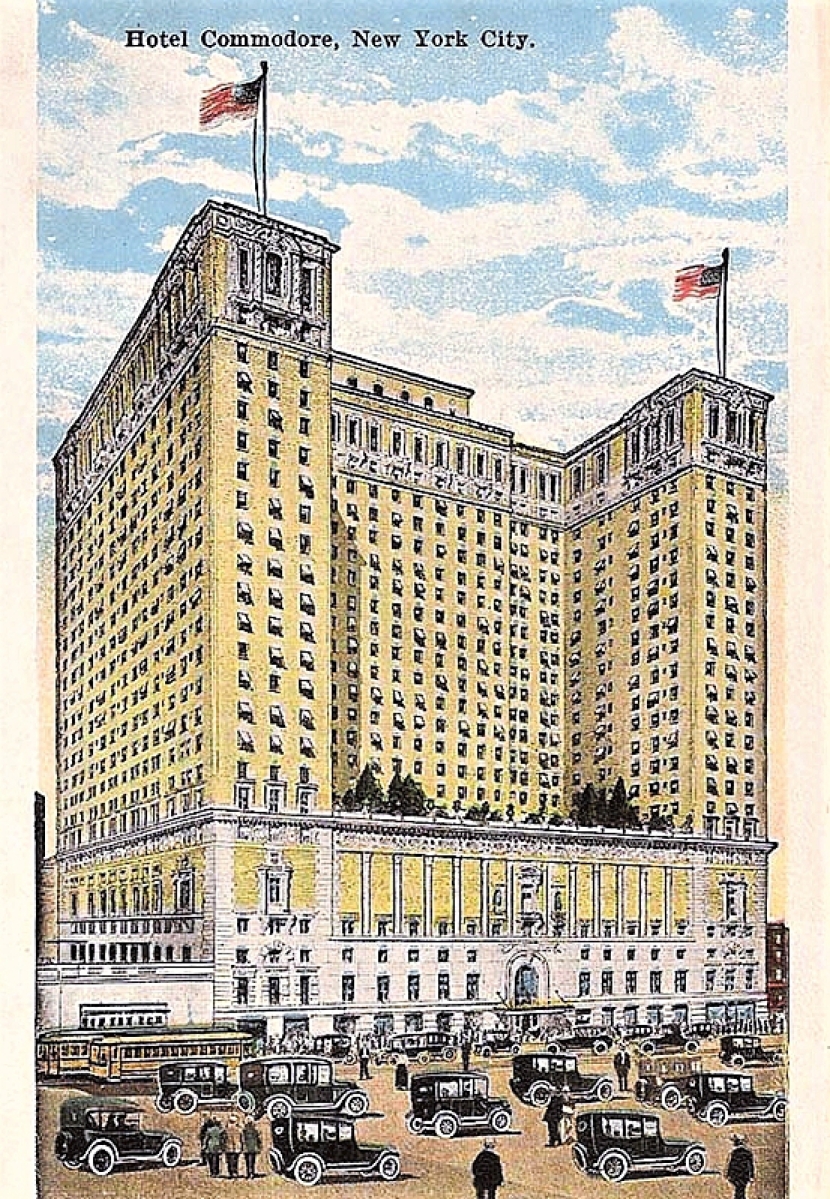

NEW YORK CITY – By the time the First International Antiques Exposition opened in the Grand Ballroom of the Hotel Commodore on March 25, 1929, the prototype of what much later would be called Americana Week, Antiques Week or now simply Winter Week – the progression suggesting something of the market’s evolution over the years – was already taking shape.

Organized by the Antiques Exposition Company in cooperation with The Antiquarian magazine, the show featured dozens of dealers from Kennebunk, Maine, to Lancaster, Penn., and beyond. It looked surprisingly like shows of today, with room-setting booths for the most ambitious vendors, glass showcases for others, and exhibitors’ names posted overhead. Heavyweights of the business, from the Americanists Charles Woolsey Lyon, Inc., and Israel Sack to English furniture purveyors Norman R. Adams and Charles of London, took part. The Petersburg, Va., dealer Mrs B.L. Brockwell offered a rare Seventeenth Century Virginia court cupboard, now a cornerstone of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts’ collection.

Spotting an opportunity, the American Art Association planned an auction of American furniture from the collection of Judge McAlpin to coincide with the fair. This simple pairing contained a kernel of what January in New York has come to mean to collectors who annually make the rounds to the Winter Show, postponed for later in 2022 as we went to press, and the sparkling assortment of satellite events that traditionally surround it.

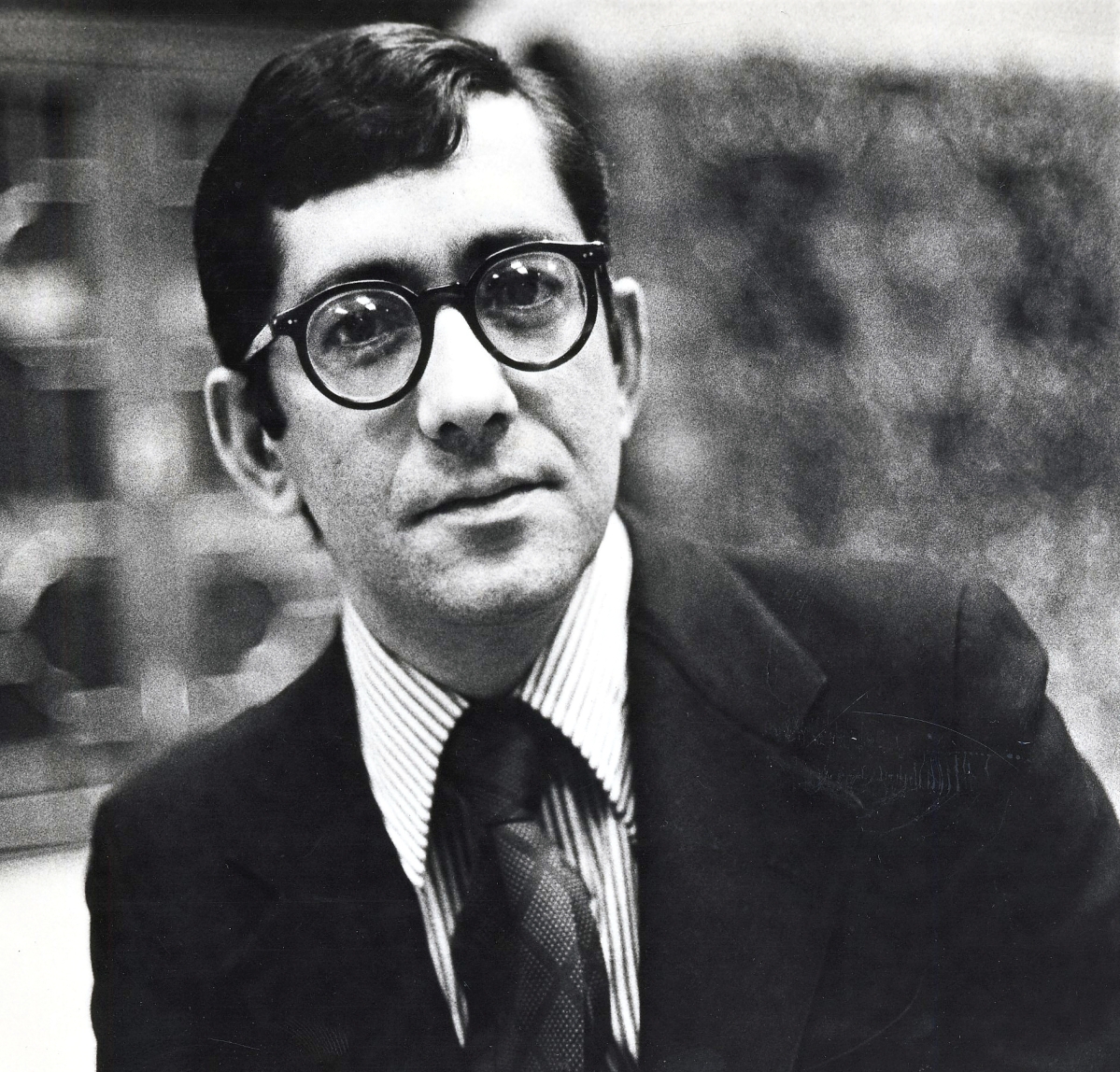

January did not always figure so prominently in New York’s antiques calendar. Acquired by the London auction house Sotheby’s in 1964, the local Parke-Bernet Galleries hosted sales throughout the year. Competition for top consignments increased after Christie’s in December 1965 announced plans to open a New York office, to be headed by the 41-year-old Picasso authority John Richardson (1924-2019). Initially looking for property to ship back to its London headquarters, Christie’s did not organize a sale in New York until 1977.

“Christie’s looked at Sotheby’s and thought, we can do that, too. London had something of a ‘wait and see’ attitude initially, but New York really took off,” says Jay Cantor, who was offered a job with Christie’s in 1977 and started with the firm the following year. “The competition created by a second major house in New York put the spotlight on auctions. The auction houses, which until then were largely a trade market, began going after private clients.”

Collector Jerry Lauren established a new record price for American folk art at auction when he acquired this J.L. Mott weathervane for $5.84 million at Sotheby’s in 2006. Specialist Nancy Druckman, here, presided over one landmark sale after the next in her 43-year career with the firm.

What most collectors think of as Americana Week emerged in the 1970s, as Sotheby’s and Christie’s staffed their New York offices with ambitious young specialists competing for domestic market share. Nancy Druckman joined Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet, then at 980 Madison Avenue, in July 1973. “We were cataloging the estate of Edith Halpert. I remember sitting in Terry Dintenfass’s gallery with my fingers plunging between the keys on a manual typewriter, pretending I could actually type,” says Druckman, who shaped the market for American folk art over the next 43 years.

Initially supervised by Ronald A. DeSilva (1937-2020), who joined in 1970 and later did a stint at Christie’s, William Stahl Jr, started at Sotheby’s in 1974. He had attended Sotheby’s sales as a college student. Once, a book dealer from Philadelphia collapsed mid-sale and was carried into an anteroom. After a polite pause, auctioneer John Marion resumed selling. “There was only one phone in the salesroom and it was for calling 911,” Stahl says wryly.

Stahl rose from a junior position cataloging American furniture to department head and finally vice chairman before leaving the company to become a consultant in 2009. Together with colleagues not mentioned, along with counterparts at other houses, Stahl presided over an extraordinary four decades of landmark sales and record prices at auction for American fine and decorative arts.

“I was on my way to graduate school when Sotheby’s hired me. I was bright green in terms of knowledge, but I knew the basics. DeSilva would come up to the warehouse and take a hard look with me or, in those days, Albert Sack (1915-2011), with whom I spent a lot of time. Kevin Tierney was on silver, Armin Allen and Tish Roberts did ceramics, and Jim Lally and Martin Lorber had Asian art. Barbara Deisroth, who was DeSilva’s assistant, decided to make Tiffany and Art Nouveau her bailiwick. We were all children.”

The first sale Stahl remembers working on was the American Heritage Society Auction of Americana. Beginning around 1971 and continuing for roughly a decade, the American Heritage sales, always in November, prefigured January’s big Americana auctions. Sotheby’s collaborated with the history magazine American Heritage to build a retail client base. As Stahl recalls, “It was a big leap of faith. The November 1974 sale was the first one where every lot was illustrated in black and white in the catalog.”

-963x1024.jpg)

Beginning around 1971 and continuing for roughly a decade, the American Heritage sales, always in November, prefigured January’s big Americana auctions. Sotheby’s collaborated with the history magazine American Heritage to build a retail client base. According to William Stahl, the 1974 sale was the first to feature a fully illustrated catalog.

Druckman adds, “The American Heritage catalogs were half the size of a phone book. We were photographing everything, even the most inexpensive cup plate. These weren’t single-owner sales of any kind of stature, just a constant flow of material. There was so much material coming through and the client base was so huge that someone at some point must have said, ‘This is crazy. We’re spending a fortune warehousing, trucking and photographing all this material.'”

American arts at Christie’s enjoyed the support of, among others, the former financier Stephen Lash, who joined in 1976 and headed trusts and estates before rising to chairman of Christie’s Americas, and DeSilva, who started in 1977. In 1978, Christie’s added the consultant and business getter Ralph E. Carpenter Jr (1909-2009), an American decorative arts enthusiast who was close to other collectors, and Cantor, who headed Christie’s American paintings department until 1989. Cantor recommended fellow Winterthur graduate Dean Failey (1947-2015) to lead American decorative arts. Failey, who started in 1979, in turn hired John Hays, with Christie’s since 1983 and a deputy chairman since 2003.

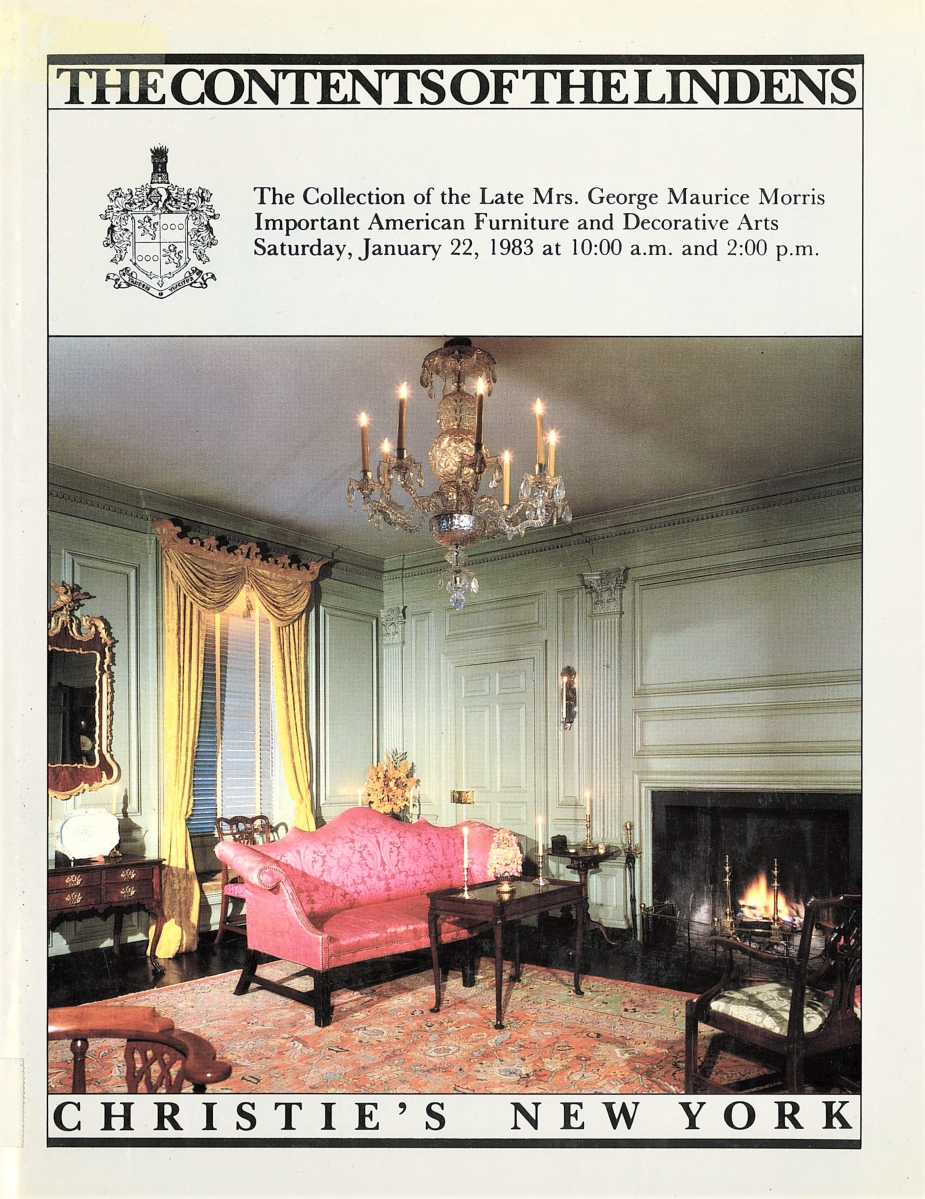

Not long after arriving, Failey and Carpenter embarked on an East Coast tour to woo consignors. One of their first visits was to Mrs George Maurice Morris, whose famous house, The Lindens, contained a foremost collection of Eighteenth Century American furniture. Christie’s pulled out all the stops to win the Morris trove, which it auctioned in January 1983 for $2.3 million, then a record for a single-day sale of Americana.

“It was our first major piece of business and it established us as players,” Failey later said.

Nobody remembers exactly when Americana Week began. As Druckman explains, “If there was an important collection out there, the client or the executor wanted it sold in January. Conversely, if Sotheby’s was going after the best, we’d say, ‘It’s for January.’ January was the top-of-the-line, the limousine sale in which you could guarantee your seller an inordinately wide group of people coming in to see and compete for the stuff. It was self-perpetuating. People wanted to be present, and you wanted them there.”

The Winter Antiques Show, rebranded the Winter Show in 2019, was the great engine driving Americana Week. The New York Times, whose lavish coverage of the 1970s and 1980s did much to build attendance, dubbed it “the Great American Show.” But American by exhibitor or by specialty? The tagline left room for interpretation.

Launched in 1955 as a fundraiser for East Side House Settlement, the Winter Antiques Show of 1965 was unequivocally American – and “early American,” at that – with urban and rural furniture, paintings and accessories offered by city and country dealers from around the United States. Perusing the catalog of the eleventh fair we find John E. Bihler and Henry S. Coger, the Massachusetts dealers said to have suggested the fundraising venture to the charity; a very young Ronald Bourgeault, at the time a dealer in Salem, Mass.; the Tillous, both Peter and his brother, Dana, in separate booths; Marguerite Riordan, then with shops in Stonington, Conn., and Watch Hill, R.I.; plus Lillian Blankley Cogan, William Guthman, Harry Hartman, Gerald Kornblau, The Old Print Shop, Maze Pottinger, Timothy Trace and other Americanists now less well known.

Exhibitors Lillian Cogan and Kenneth Hammitt at the 1965 Winter Antiques Show. The fair had a strong American flavor for much of its first three decades.

The Winter Show of today is a carefully balanced ensemble performance, with 69 exhibitors, most of whom have an international following and more than a third of whom maintain an overseas address. Its “best of the best” ethos emphasizes a stunning range of merchandise, from ancient to contemporary, all of the highest quality.

The Winter Show’s evolution, and that of the market itself, was hastened by the London promoters Anna and Brian Haughton, who debuted the first major vetted antiques fair in New York, the International Fine Art and Antique Dealers Show, in 1989, and by Sanford L. Smith, the impresario most responsible for popularizing a host of new collecting categories, from folk art to modernism, self-taught art and contemporary studio design.

In his privately published memoirs of 2010, Recollections: A Life in New York, Smith recounts his first foray into antiques after marrying in 1964. On weekend visits to Connecticut to see family, the young couple began frequenting country auctions. Their haul – “for $25 you could fill up a whole station wagon” – became inventory when they rented a stall at a New York City flea market. After graduating to the National Antiques Show at Madison Square Garden – described by New York Times antiques columnist Rita Reif as “the most diverse bazaar around, offering a bonanza of mostly vintage wares from about 290 dealers, exhibits of collectibles from about 30 other sources, an ‘appraisers’ clinic’ and a stamp and coin corner” – Smith got better acquainted with the producer of both events, Nathan H. Mager (1912-1986). Mager agreed to help him secure the Seventh Regiment Armory at 66th Street and Park Avenue, on New York’s Upper East Side, for a new show of Smith’s own if the fledgling manager agreed to work with Mager’s daughter, Alison. It was a short-lived partnership.

Sanford Smith’s Fall Antiques Show debuted at the Seventh Regiment Armory on September 11, 1979, with a fundraising preview catered by Martha Stewart, then all but unknown, for the Museum of American Folk Art, whose director, Robert Bishop, also dabbled as a dealer. New York City mayor Ed Koch declared a Folk Art Festival through September 16. Much like future Americana Weeks, the Folk Art Festival was a cornucopia of events meant to draw collectors to the city. It featured an exhibition and symposium on Shaker art at the museum, plus an auction at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet organized by Stahl, by then a Sotheby’s vice president, and Druckman, the house folk art specialist.

In its second year the Fall Show moved to the New York Passenger Ship Terminal, a venue Smith helped popularize for promoters who followed him in that space, most notably Irene Stella, whose Triple Pier Antiques Show was a smash hit. Stella Management also organized Antiques at the Other Armory, for years an integral part of January’s Americana Week.

First at the armory, then at the piers, then back at the armory, the Fall Antiques Show made prominent many of the aspiring young dealers who soon became the pinnacle of the trade in American country antiques and folk art. After it folded in 1999, the Fall Antiques Show regrouped as the American Antiques Show, managed on behalf of the American Folk Art Museum by Keeling Wainwright Associates, followed by Karen DiSaia. The American Antiques Show was a vital feature of January’s Americana Week calendar until it too closed.

The Fall Antiques Show was an important influence on the developing market for American country furniture and folk art. This 1995 photo shows shoppers lined up around the corner to enter the fair at New York’s Seventh Regiment Armory. Photo courtesy Sanford L. Smith & Associates.

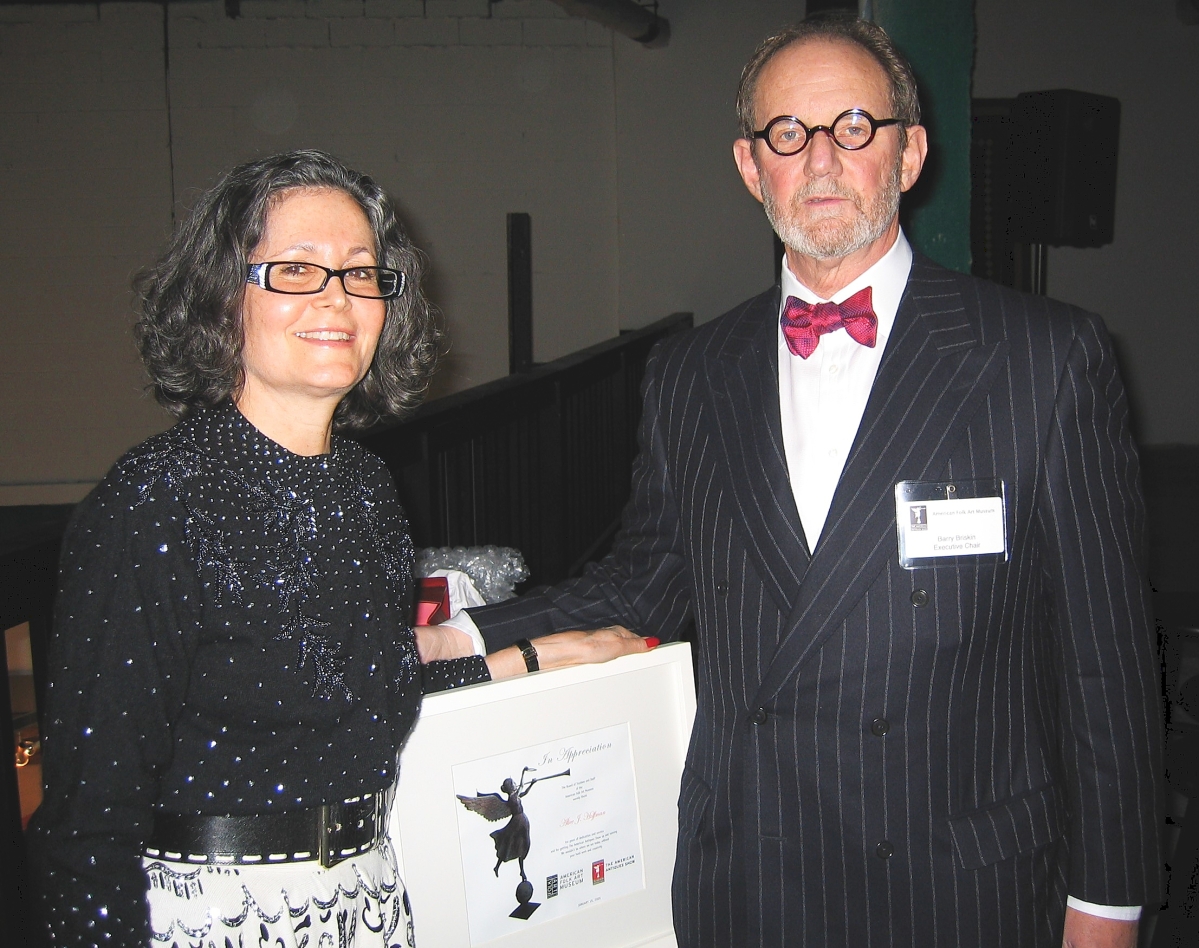

Smith continued to innovate, both anticipating and influencing collecting trends. According to his website, he introduced Modernism in 1985; Works on Paper in 1986; the Photography Fair in 1989; the Outsider Art Fair in 1993; the National Black Fine Art Show in 1994; Art 20 in 2001; PAD NY in 2011; and PAD’s successor, the Salon Art + Design in 2012. In 2010, the American Folk Art Museum presented Smith and the Outsider Art Fair with its Visionary Award.

As Smith recalls, the Outsider Art Fair began with a suggestion from his son, Colin, and an assistant, Caroline Kerrigan; and took shape over a lunch with dealers Aarne Anton, Roger Ricco and Frank Maresca; and is today owned by gallerist Andrew Edlin. Now 30 years old, the fair returns to New York’s Metropolitan Pavilion March 3-6 after it announced last week that it would reschedule the event one month after it was originally planned out of concern for the rising spread of the omicron variant. Like the Fall Antiques Show before it, it anchors its own constellation of events, normally including Christie’s auction of Outsider art organized by Cara Zimmerman, which will take place as originally planned on February 3. The Christie’s specialist and Americana department head has turned Outsider and self-taught art into a marquee specialty for the New York house, which holds record prices for artists Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, William Edmondson and Thornton Dial, among others. In January 2016, Christie’s auctioned Edmondson’s “Boxer” for $785,000, demonstrating the dramatic growth of the field since the Outsider Art Fair’s debut nearly 30 years ago.

Changing tastes, market downdrafts, evolving technology and a prolonged public health crisis have altered what we once thought of as Americana Week, threatening it again this year. But Americana Week’s features, if faded, are still distinct to those long attuned to them.

“Quite honestly, I love the idea and excitement of Americana Week,” says Erik Gronning, a Sotheby’s senior vice president who joined the company in 2004 and heads its Americana department. Even as he acknowledges broad changes in the way audiences consume both art and media, collectors of Americana remain a breed apart, he says. “In a way, we are all disciples of Henry Francis du Pont or Wallace Nutting. People who love Americana don’t collect in a vacuum. They want to be surrounded by the culture, by beautiful handmade objects. If they buy andirons, they also want everything else in and around the fireplace and the room it warms.”

“A diverse sale attracts a wide audience and excites bidders’ imaginations,” continues Gronning, a master of ambitious, single-owner sales. This year is no different. On January 22, Sotheby’s is offering, in four sessions, 650 lots from the collection of William K. du Pont. Gronning notes, “Bill was a larger-than-life character who loved a great story and was fascinated by many things. As a collector he was always adapting and changing. We’re selling pieces that haven’t seen the light of day in 45 years, some with excitingly low estimates.”

“Through the 1980s, we were the little guys,” says John Hays. Entering his fifth decade at Christie’s, Hays sees evolution in the marketplace for Americana even as many of its core values remain. “There is some rethinking about how we position all pre-modern art. American, English or French, we think of it as classic. But after decades of tradition, the passion for the American experiment and the art that it produced still has, without sounding jingoistic, huge appeal for many collectors.”

Hays’ approach to selling Americana has long been evident to market watchers. Christie’s Americana department is known for highly tailored sales emphasizing high-value properties. On January 20, the company is offering American folk art from the collection of Peter and Barbara Goodman, discriminating buyers with an eye for color, form and pattern. The star of its January 20-21 Various Owners sale is a circa 1755 Philadelphia Queen Anne armchair from the collection of the late Martin Wunsch (1924-2013). Albert Sack (1915-2011) regarded it as the foremost example of its kind. Hays says simply, “Americana Week changes over time, but Christie’s continues to find and offer pearls.”

Technology has transformed the way art is bought and sold, especially for international giants with capital to invest. As Hays notes, “We prefer live audiences, but we had to pivot. Our salesroom now looks like the Starship Enterprise, with television cameras and multiple screens. We’ve become very good at selling online. It took time and money, but we did it.”

Even as technology upends old ways of trading, the urge to gather as a community, to experience art’s tactile dimensions firsthand, has never been greater. Gronning and Hays cite as examples the packed galleries and general exuberance of Sotheby’s and Christie’s blockbuster fall 2021 sales of contemporary art.

Helen Allen, executive director of the Winter Show, notes, “While our online show in 2021 was a success, people are yearning to return to the show and to see the works in person. Prior to Covid, the Winter Show had been working to engage with expanded audiences, seen through initiatives such as special access hours for designers and ongoing collaborations with young, leading voices in art and design at Young Collectors Night.”

After more than half a century of experimentation, all parties agree that a lively calendar brings buyers to New York, even in the deep of winter. For the Winter Show – which was set to debut on January 20, but, disrupted by omicron, is seeking new dates in early 2022 – collaboration is the watchword. “It makes life much more enjoyable and creates more dynamic programming,” says Allen, who partnered with Master Drawings New York, Asia Week New York, Sir John Soane’s Museum Foundation, the American Friends of the Louvre and New Vessel Press, among others, to provide an array of in-person events at the show, most of which will now move online. (Scheduling details for all will be provided at www.thewintershow.org as they become available.

For a bit of perspective on recent events, the Winter Show’s disruption in 2021 and 2022 is historic, but not unprecedented. Forced to vacate the armory in 1957 and 1958, the fair returned to Park Avenue in 1959, as vibrant as ever. After the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, the armory’s drill hall was requisitioned by the National Guard. The Winter Show took refuge at the Hilton New York. A set up that normally took a full seven days was accomplished in just three and a half. The crew was still moving ladders when the show opened at 5 pm on Saturday, January 19, 2002, with Mayor Michael Bloomberg in attendance.

Allen spent Christmas weekend calling exhibitors to relay the unhappy news of the show’s postponement. She told dealers, “The Winter Show and East Side House Settlement are completely committed to you and to giving you a space in which to present.” The overwhelmingly positive response she got from her dealers moves Allen to say, “What really strikes me about this show is that we are family.”

And that is the essential point. The great community of collectors, curators and commercial art experts who gather in New York in January will continue to do so, so as long as there are great sales, important objects, not-to-be missed shows and the fellowship of other enthusiasts to draw them there. Long live Americana Week.

.jpg)