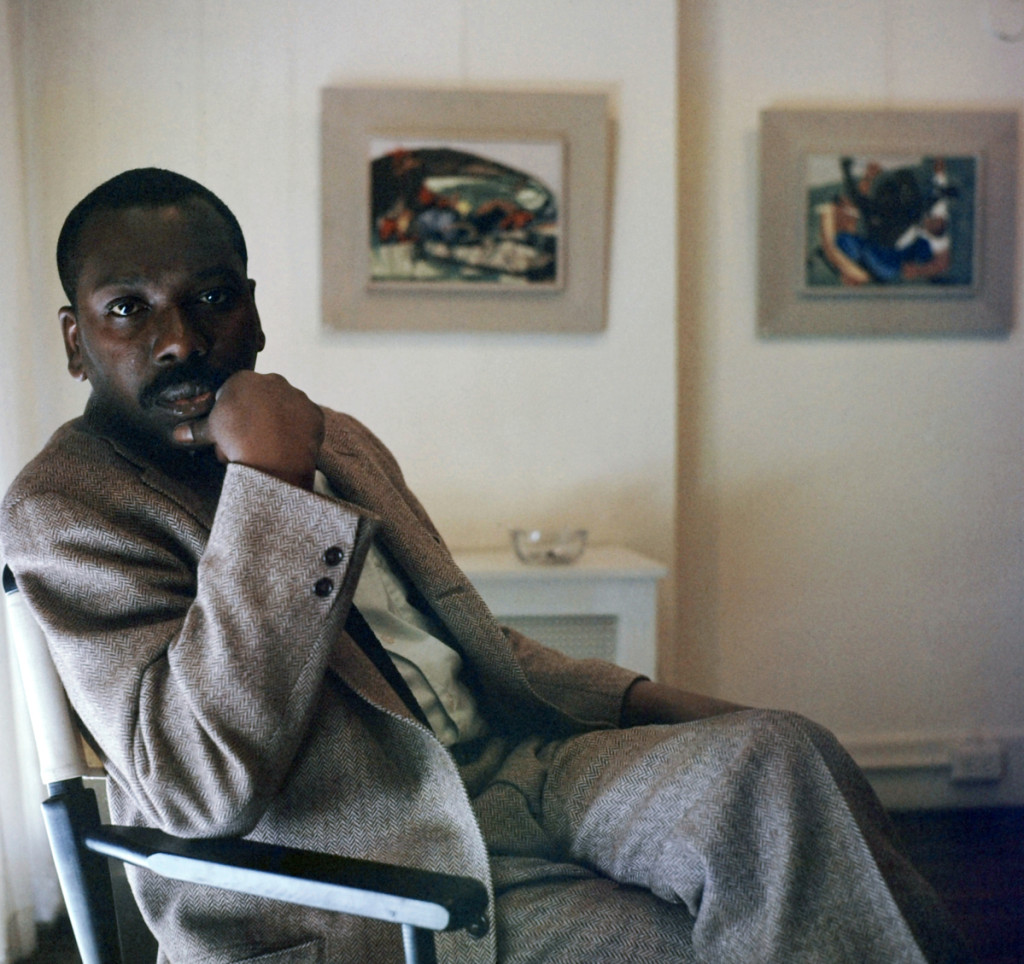

Artist Jacob Lawrence with Panel 26 and Panel 27 from “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” 1954–56. ©Robert W. Kelley/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SALEM, MASS. – A prodigy of the Harlem Renaissance, Jacob Lawrence has long been recognized as one of America’s premier artistic chroniclers of African American life and history. His mid-career painting series, “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” was something of a departure for him: on first glance, a whiter, more standardized, schoolbook version of the founding of the United States. Sold to a private collector and broken up over time, the series is less known and less studied than many of his other great historical cycles; the temptation is to assume that it somehow was or is less successful. But a new exhibition that brings 25 of the 30 original paintings together for the first time since 1957 argues that Struggle attempts and, in some respects, achieves at least as much as, if not more than, other more acclaimed works in Lawrence’s oeuvre. “Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle” is on view at the Peabody Essex Museum January 18 through April 26.

Lawrence was already a rising star, having painted acclaimed historical series on the lives of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and Toussaint L’Ouverture, when he staked his permanent claim on American art history with his much-lauded “Migration” series. Completed and exhibited in 1941, when he was just 23 years old, the series has introduced many an American to the historical phenomenon of the Great Migration, during which second- and third-generation descendants of enslaved people moved en masse from the American South to northern cities in the early Twentieth Century, in search of both economic opportunity and relief from Jim Crow apartheid. With the series’ acquisition by the Museum of Modern Art, Lawrence broke the color barrier of the famously white-dominated New York art world, and he did it with work that spoke directly to the African American experience.

There was little opportunity for Lawrence to immediately follow up on this early, brilliant success. Within two years, he was drafted into the US Coast Guard, serving in that branch’s first integrated crew, one of the earliest integrated regiments in the US armed forces. In the role of combat artist, it was part of his job to document the daily lives of the soldiers aboard his ship, and he put that experience to use after his return from World War II. By 1947, he had completed his “War” series, completed with the support of a Guggenheim grant and quickly acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art. In this, as in his preceding series, he refreshed and reenvisioned the traditional genre of history painting with his elemental modernist style and with the choices he made about scale, presentation and subject matter.

The present exhibition’s curators – Elizabeth Hutton Turner of the University of Virginia, formerly of the Phillips Collection, and Austen Barron Bailly of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, formerly of the Peabody Essex Museum – argue that Lawrence’s wartime experience engendered not only the “War” series but also “Struggle,” which he began researching in 1949 and completed over a three-year period from 1954 to 1956. The triumph of the Allied victory was cause for celebration in America, but there were also the realities of the toll that the war had taken, reflected in “War” series canvases like “Depression” and “The Letter.” It is no coincidence, then, that so much of the “Struggle” series also deals with war, primarily the American Revolution and the War of 1812, and similarly tries to balance rejoicing with loss.

“Rally Mohawks! Bring out your axes, and tell King George we’ll pay no taxes on his foreign tea… — a song of 1773” by Jacob Lawrence, Panel 3, 1955, from “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. ©The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Bob Packert/PEM.

“He’s definitely wanting to celebrate people that were there, and the eyewitness accounts and the struggle,” says Turner. “These are people in the midst of struggle that don’t know the outcome, aren’t sure of what the future may hold, but they know what they’re ready to fight for, lay down their life for…. The lengths that people will go to get their freedom really underscores the principles underlying the American nation.” Turner also notes that the “Struggle” paintings were produced during a time when American life was fractured by fears of possible nuclear holocaust, by McCarthyism, and by growing racial strife, all topics in which Lawrence was personally invested. In the “Struggle” series, Turner says, “he found a mechanism for the way art can intervene and for it to begin to speak to the heart and mind of the viewer.”

He did this, in part, by resisting the fantasist, heroizing impulses that had characterized history painting in previous generations. His soldiers, statesmen and other patriots do not embody the chiseled ideal of ancient statuary, nor do they strive for a dazzling, flesh-and blood verisimilitude -all are depicted in the flat, semi-abstract style of the artist’s earlier series, with an added element of fractured cubism that makes the paintings seem kaleidoscopic and hectic. They go about their business with grim determination: dirty, bloody, exhausted, heads down and jaws set. Even in compositions that focus primarily on a single figure – the one dedicated to Margaret (“Molly Pitcher”) Corbin, titled “And a Woman Mans a Cannon,” is a key example – the protagonist does not stand as if on a stage but is fully integrated into the surrounding action, just one figure in a much larger struggle.

Focusing on real people and real first-person accounts is another way in which Lawrence makes history feel real to viewers. Choosing people and passages that occupy the margins of conventional history ensures that the sense of realness goes beyond the standard narratives that center the contributions of white colonists and settlers. “I think that he is laying claim to mainstream American history,” says Bailly, “by imagining what he as an American artist, as a black man and a black artist, what his version of American history would be.” He does this, it is crucial to point out, not through revisionism but through meticulous research, digging deep into the stories of Crispus Attucks, Sacajawea, Tecumseh, the unnamed enslaved people who petitioned for their freedom in 1773 and rebelled in 1810, the immigrants who left all they knew, the workers who built the canals and many others. He also distilled lesser-known phrases and moments from iconic events and speeches – the closing lines from Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” speech and the Declaration of Independence; a forgotten passage in Henry Clay’s address to Congress in which he imagines the tribulations of a single sailor impressed into involuntary servitude; the moment when Sacajawea, stolen from her family as a child, realizes that the Shoshone chief she is translating for is her brother, Chief Cameahwait – even as she provides a point of entry to her homeland that would eventually end in genocide.

“He had such a capacity of synthesizing and also the ability to read history,” said Turner of Lawrence. “These narrative cycles start in the library, and he’s reading these passages, and then he’s visualizing it, and then he’s codifying it and putting words with images…to propel you through the narrative.” Indeed, most of the 25 known paintings in the series – the five paintings missing from the show are currently unlocated – are inscribed with the text upon which they are based, usually on the back of the canvas. One of the great contributions of the present exhibition has been to identify the sources and the historical events to which each painting is connected, and to codify their titles to reflect those sources. The result has been to underscore the intellectual and historical rigor of the series, and to allow it once again to be read as a continuous – if not strictly progressive – narrative, with each canvas blending word, image and historical fact to parse an aspect of the evolving struggle for freedom in the United States.

“. . . for freedom we want and will have, for we have served this cruel land long enuff . . . —a Georgia slave, 1810” by Jacob Lawrence, Panel 27, 1956, from “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” 1954–56. Egg tempera on hardboard. Private collection. © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Given that rigor, given the reverence with which Lawrence clearly regarded the founding stories of America and the principles under which they were founded, and given the wide public and institutional respect that he enjoyed, why should this series have gone so underrecognized? How can it be true that the Peabody Essex Museum’s installation is its very first museum showing? The curators parse this question thoughtfully. Some of it has to do with how it was produced and funded, Turner notes. Whereas Lawrence had the support of the Guggenheim Foundation for the “War” series, “Struggle” was made essentially on spec, with the hope of funding it as a continuing project through sales. And while those first 30 paintings did sell, as both Turner and Bailly are quick to point out, the purchaser, perhaps seeing it as an investment, relatively quickly turned around and resold the paintings individually. “The whole coherence of the project got eroded early on,” Bailly observes, “and Lawrence himself moved on,” giving up on creating more works in the series. Thus, among the other misfortunes, the series has suffered is the lingering presumption that it is “incomplete.”

The hesitant public reception may also have had something to do with the aesthetic tastes of the time. Turner notes that the series’ debut coincided with the rise of Abstract Expressionism, which had eroded the popularity of the kind of narrative, figural art that Lawrence was doing. Bailly also notes that Lawrence was “pushing his style in some pretty intense directions” with “Struggle” – “more angular, prismatic expressions” that may have been outside the comfort zone of some collectors. But it could also be that the history itself, Lawrence’s take on the cherished origin stories of the United States, was also outside viewers’ comfort zones. He was a black artist, known for painting black history (with the partial exception of the “War” series), and “the idea that he was moving into American history writ large…. I think that people weren’t quite sure what to do with that,” says Bailly.

Lawrence’s attempts to tell American history as a history of struggle, and to center the voices of those directly engaged in that struggle, is deeply reminiscent of a recent, similar attempt, the New York Time’s “1619 Project,” a special section in 2019 focusing on how those who suffered under chattel slavery, and their descendants, have served and yearned for the American promise of freedom, independence and democracy. In an introductory essay in the catalog for “Jacob Lawrence: An American Struggle,” scholar Stephen Locke articulates how Lawrence’s series is a similar exercise in truth-telling, breaking from earlier, more rose-colored histories. “Not another history of winners and losers or another history presented by the people on the top at the expense of folks on the bottom,” Locke writes, “his is a more productive way to image America because it shows that the country is conceived in conflict and combat, debate and divisiveness. And in developing a new form to talk about struggle, Lawrence gives us a new framework to understand the American experience.”

It makes a certain amount of sense that this framework is, to some extent, incomplete – the full series, as imagined, was never realized, and only 25 of the completed paintings have been identified, located and are on view today. In acknowledging these gaps, the exhibition allows for the possibility that new histories are yet to be written and envisioned; in fact, the Peabody Essex Museum has invited three contemporary artists – Bethany Collins, Hank Willis Thomas and Derrick Adams – to create artistic and written responses for the exhibition.

“It’s not finished in the way that America is not finished,” says Turner of Jacob Lawrence’s “Struggle” series. “If it’s not finished, then the unfinished business is ours. It’s up to us to keep deeply thinking this through.”

The Peabody Essex Museum is at 161 Essex Street in Salem, Massachusetts. For information, www.pem.org or 978-745-9500.