Jim Julia presided over a $3.65 million auction of fine and decorative arts in August 2017.

The lion, a crowd-pleaser, found a new home with Pennsylvania dealer Diana Bittel.

By Rick Russack

FAIRFIELD, MAINE – Late last year, after a decades-long career as a leading auctioneer, Jim Julia announced that he was stepping away from the podium. Effective December 14, the James D. Julia firm merged with Morphy Auctions. Operations will be transferred to Morphy’s Denver, Penn., headquarters after James D. Julia’s final sale March 21-23.

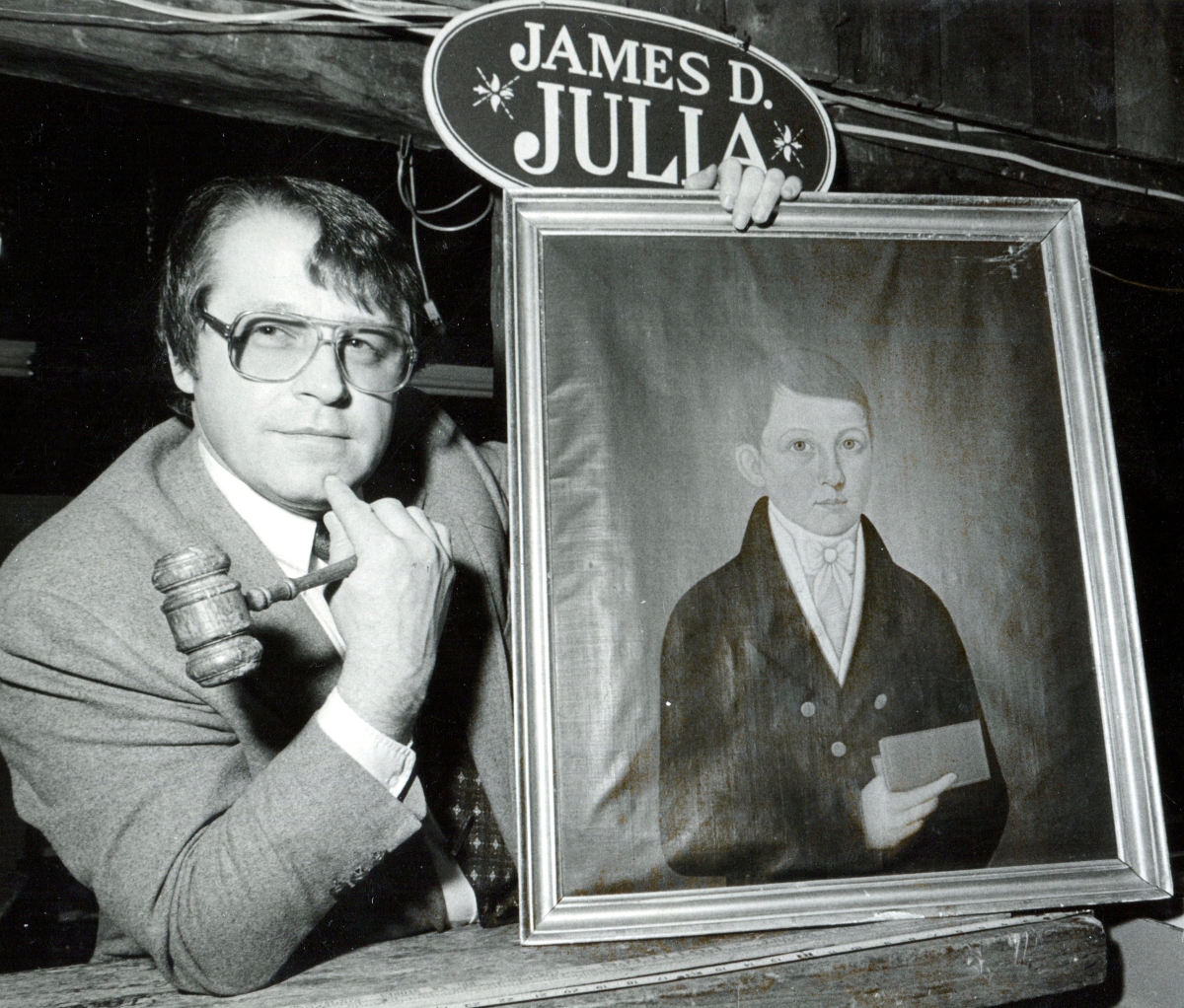

Jim, as he is called by colleagues and friends, recently reminisced about his highly successful tenure, describing the changes he saw and innovations he introduced. Over the years, James D. Julia sold defining remnants of American history: the only Colt revolver positively identified as having been used at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, a rifle that shot Bonnie and Clyde, Al Capone’s pocket watch, a powder horn that may have been used at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and many more.

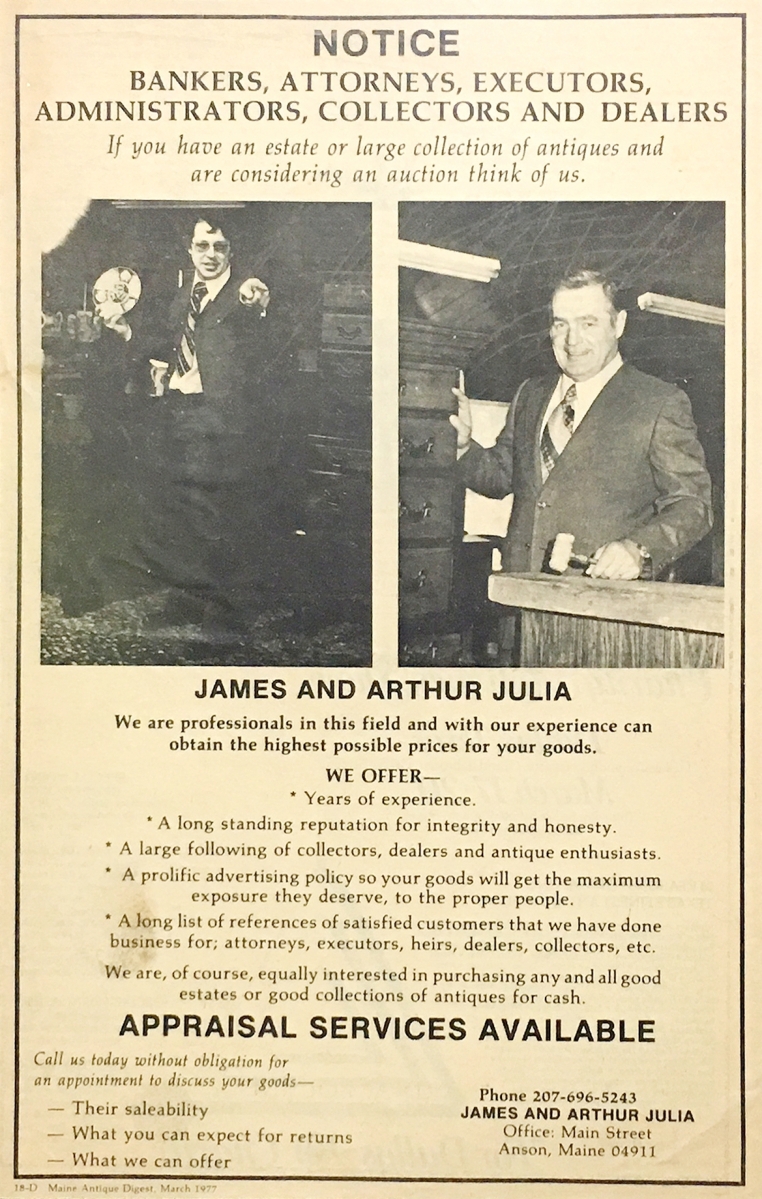

Jim’s first exposure to the auction business was in the mid-1960s when he helped his father, Arthur Julia, at his Saturday night auctions, affairs that typically grossed around $1,000. Fast-forward 50 years. Julia’s December 2017 firearms sale grossed more than $15 million. His 2017 sales overall exceeded $45 million. But the Jim Julia story is not about dollars. It is about a goal of becoming one of the top auction houses in the United States. With growth in mind, Jim instituted guarantees, introduced a competitive commission schedule that goes as low as zero based upon the value of consignments and employed recognized experts to describe and catalog the material he offered.

The auction business Jim grew up in was a family affair. He was one of seven children, all of whom helped any way they could. At his father’s second sale, Jim took over the podium, giving Arthur Julia a break. As Jim recalls, “It was a challenge for me. My very first night, I didn’t know how to control my voice. As the bids got higher and the excitement grew, my pitch increased like the Vienna Boys Choir. It was rather humorous.”

Once Jim was involved with the business, his father would give him some money and send him out “picking,” knocking on doors to buy as much as he could. “I loved rummaging through barns and attics full of old things, and the family stories fascinated me. I’d often encounter families whose roots went back to the Revolutionary War, or even earlier,” he says.

There was an art to being a picker and each picker developed his own approach. He says, “It was like being in the Klondike in the 1890s. Gold nuggets were everywhere in the form of Victorian and earlier furnishings, folk art and an incredible array of other antiques. A unique phenomenon had taken place after World War II. Traditionally, farms and homes were passed on to the oldest son. Now many of these young men, having had exposure to the wider world during the war, were choosing a different way of life, moving off the farms into the cities. Many old homes and farms were in the hands of those who would likely be the last generation of that family to own the property. The children often had no interest in the old stuff in their parents’ homes and attics.

There was an art to being a picker and each picker developed his own approach. He says, “It was like being in the Klondike in the 1890s. Gold nuggets were everywhere in the form of Victorian and earlier furnishings, folk art and an incredible array of other antiques. A unique phenomenon had taken place after World War II. Traditionally, farms and homes were passed on to the oldest son. Now many of these young men, having had exposure to the wider world during the war, were choosing a different way of life, moving off the farms into the cities. Many old homes and farms were in the hands of those who would likely be the last generation of that family to own the property. The children often had no interest in the old stuff in their parents’ homes and attics.

“The major challenge as a picker was to get into the house,” he continued. “When I knocked on the door, I gave the homeowner a business card identifying myself and described what I was interested in buying. The important thing was to somehow purchase the first item. I asked for items that were likely to be found in the attic, cellar or sheds. Sometimes, if I was standing in the doorway, I could see a piece of furniture that had some value and I’d make an offer far in excess of the true value of that piece. If I was able to buy the first item, the likelihood was that I would be able to purchase other items, making up for my loss on the first one.”

Jim graduated from college with a degree in biology and taught high school for three years. A teacher’s work schedule left him time to continue picking and helping his father. In the early 1970s, after his father declined a particularly good collection, Jim arranged to buy his father’s business and become an auctioneer.

“It was always my intention to build a business that would extend beyond the state of Maine, but there was a lot to learn,” he said. “It was an exciting period, meeting with dealers, heirs and collectors about consignments. I worked hard at organizing quality, onsite auctions. Onsite sales were absolutely the best way to sell in the 1970s and 1980s. For buyers and sellers, it was a unique experience. Last-minute discoveries, items soaring far above what you had anticipated and bidding battles erupting between moneyed players resulted in some truly exciting moments. There was plenty of money to be made.”

He adds, “I had taken a Dale Carnegie sales course and it taught me some important lessons. First, decide what you want. Second, think in terms of your customer. I learned to practice the old Avis slogan – ‘We Try Harder.'”

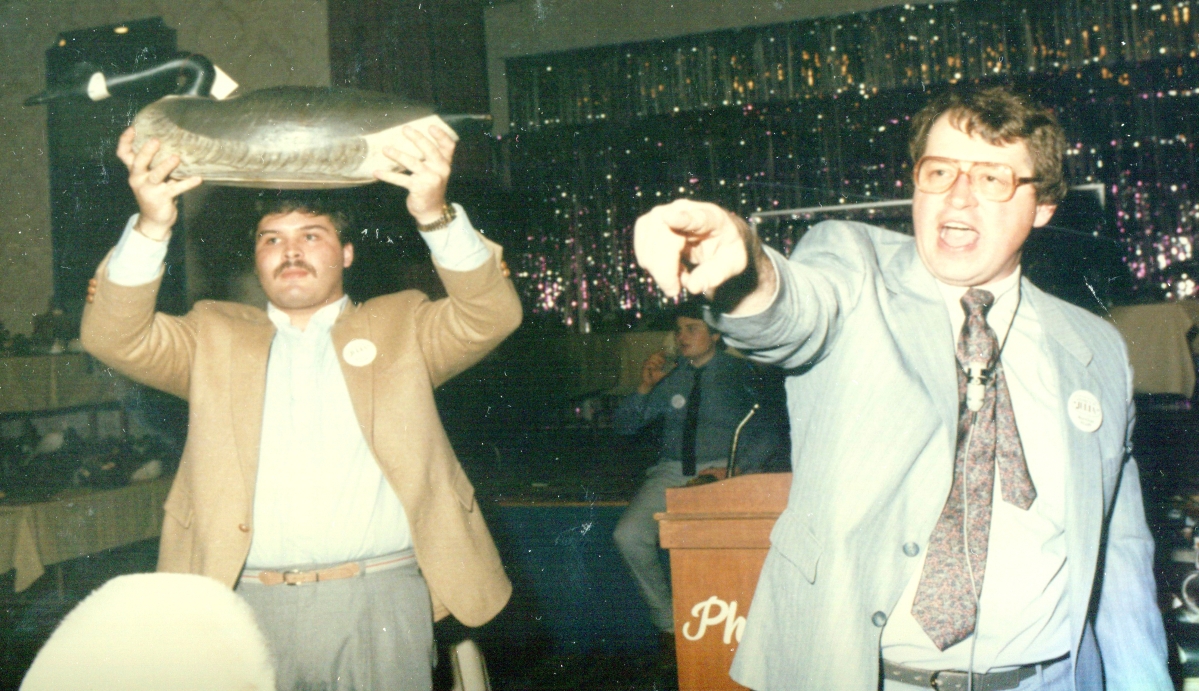

Jim, right, teamed up with decoys authority Gary Guyette, left, in 1984. They auctioned the Joseph Lincoln hissing goose for a record $90,200 in April 1985. Jim sold Guyette his share of the decoys business seven years later, but still calls sales for Guyette & Deeter.

Jim soon realized that it was easier to convince owners to sell at auction rather than to a dealer. “As a dealer, I wanted to buy at the lowest possible price. That put me in an almost adversarial role with the seller. But an auctioneer is paid a percentage of what he gets for something. The higher the selling price, the more we’d both make, and that changed the dynamics. I always talked in terms of the seller’s best interest. I explained that the auction process would generally result in the item bringing its fair-market value. More and more of my energies focused on auctions. I knew that getting strong results for sellers would get me more quality goods and estates. That was important to me. I poured as much money as I could into advertising and marketing. From the very beginning, the objective was to get bigger and better at what I was doing. I was always on the lookout for marketing techniques or things I could do to improve results.”

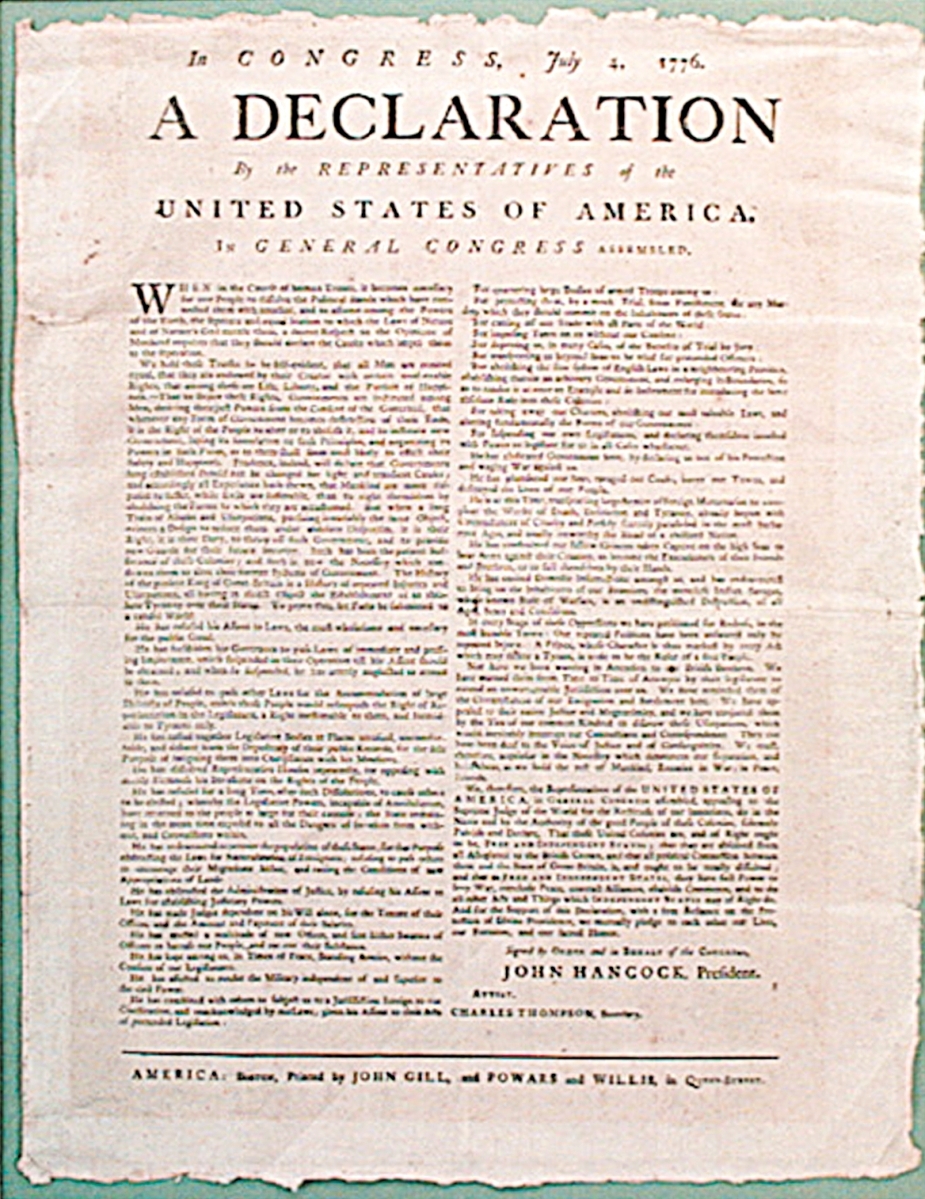

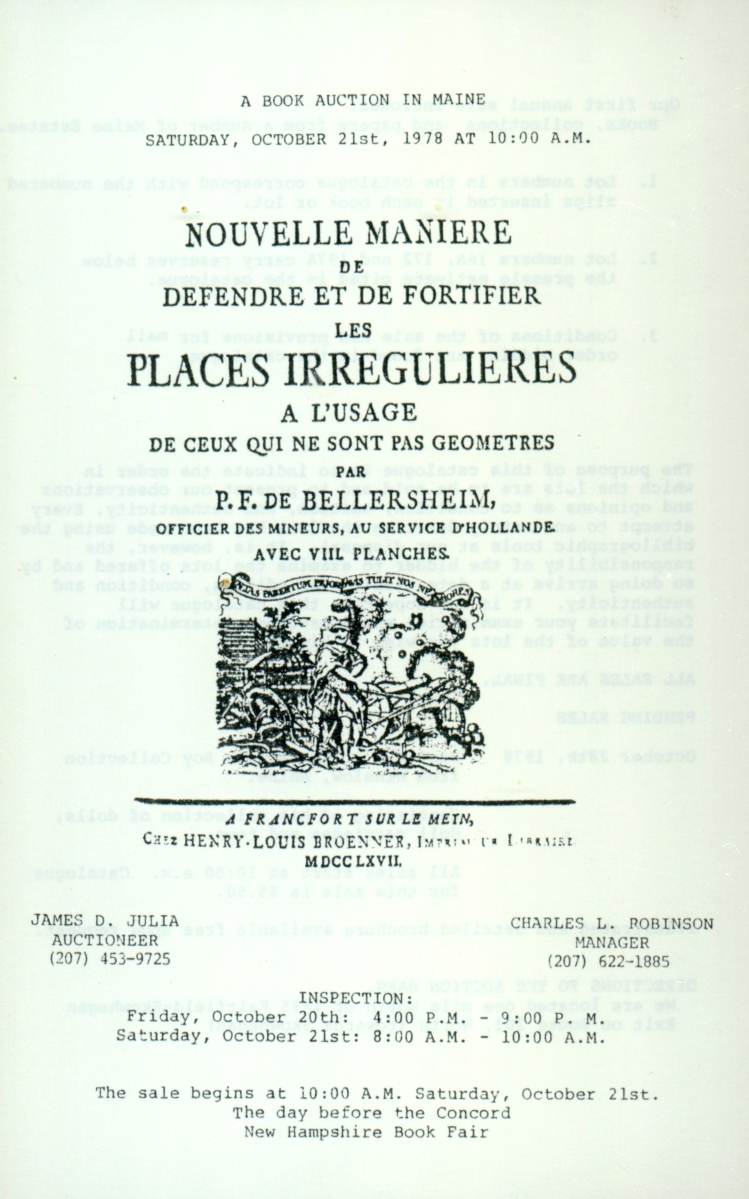

Despite early successes, many potential consignors were skeptical that Julia could get top dollar for their goods in a rural venue. One tactic was to conduct sales in rented facilities, closer to major markets. Catalogs were of more lasting value. Jim explains, “I needed to take my client’s goods to a larger audience. That would give my consignors an advantage and give more people a reason to do business with me. I realized that if I sent catalogs all over this country and to other parts of the world, I would increase the number of bidders, effectively upping the return for me and my consignors. My first catalogs were for rare books. With the help of Dr Charles Robinson, a knowledgeable bibliophile, we conducted a number of successful auctions.”

Jim reflects, “I learned several things about catalogs from those early book sales. An honest catalog describing each item, with condition reports, increased the number of absentee bids and, therefore, the final prices. Catalogs needed to be produced by recognized experts. The more catalogs I could distribute, the higher final prices would be. Specialty auctions, as opposed to general auctions, were definitely the way to go. Catalogs were important in convincing consignors to do business with us, and the postsale prices realized list was very important. It not only became a source of knowledge, it showed potential consignors exactly how successful our auctions could be. Here was the item, here was our description, here was the condition report, here was the presale estimate and here was the selling price. It worked.”

The next time Julia used comprehensive catalogs was when Jim started dispersing a large glass collection. He retained as a consultant Louis O. St Aubin Jr, a noted expert in American glass who died in 2006. “Louis’s involvement in my auctions drove home other points that I consider critical to my success. Whenever you utilize outside experts, you must ensure that they really know their stuff, that they have a great reputation in the community and, hopefully, that they are in the trade and know current prices. I have to be certain to publicly use the expert’s name in addition to my own. As long as I selected great catalogers and consultants, my company became accepted almost overnight each time I entered a new specialty,” he says.

Julia advertised these specialty sales in specialty publications. As a side benefit, the cataloger often promoted the sale to his contacts in the field.

Sandy and Jim Julia pause for a photo during their final fine and decorative arts auction in February 2018.

James D. Julia produced catalogs for books, lamps and glass, toys and dolls, advertising, decoys and firearms. Jim says, “I saw that multiple, high-quality photographs were essential. We utilized professional photographers who, over the years, honed their skills. The photography in our catalogs, particularly the firearms catalogs, is, I’m told, the finest in the trade. Color is important in everything, but particularly important in firearms. If a gun retains some original finish, it’s worth a premium. If it has a fabulous original finish, then the price can be extraordinary. Subtle differences in color, wear and bluing have a tremendous effect on value, so quality images really help the buyer, the seller and the auctioneer.”

Getting into the decoy business was also a shrewd move. A local picker wanted to sell a group of decoys from Canada’s Maritime provinces. “He had been buying the decoys for a bit and had put together a nice group. He said that if I would create one of my catalogs and include a few photographs, he would give me the entire consignment. I thought that the decoy world had potential and I wanted to try this experiment. I needed someone to do the catalog. The only person I knew at the time was Gary Guyette, who had written a book on Maritime decoys. He loved decoys, was very knowledgeable and had a good reputation in the field. He did the catalog and helped potential buyers. The sale was very successful. After the auction, I spoke with Gary and told him I thought there was tremendous potential in this field. I asked if he would like to work together doing specialty decoy auctions.”

That was the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship. In 1991, Jim sold his interest in the decoy company to Guyette but continued to call Guyette’s sales.

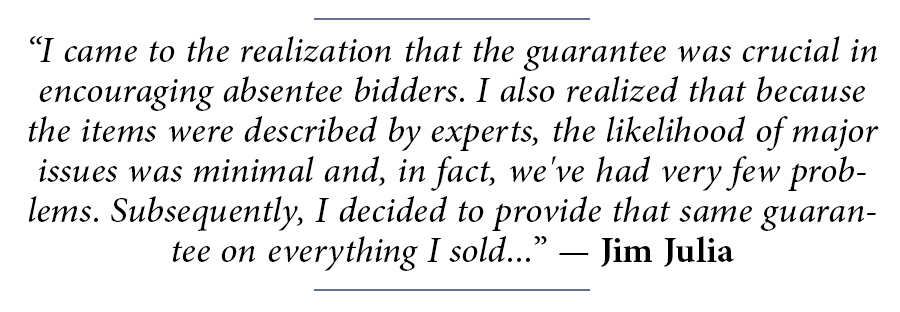

A key lesson learned from the decoy auctions added another important element to Julia’s way of doing business: a full guarantee that items in the catalog were exactly as described. Jim says, “The decoy sales introduced me to another important sales tool that helped set my company apart from most others: the guarantee. There were only a couple of decoy auctioneers, and it was standard to guarantee the decoys. So Gary and I guaranteed everything we sold. After doing that for a few years, I came to the realization that the guarantee was crucial in encouraging absentee bidders. I also realized that because the items were described by experts, the likelihood of major issues was minimal and, in fact, we’ve had very few problems. Subsequently, I decided to provide that same guarantee on everything I sold, not just decoys.”

Julia’s soon added another protection for buyers. Jim notes, “We worked hard to develop a reputation for honesty and fair dealing, so we also elected to take a very open approach to problems noted by potential buyers. We made it clear that if you examined anything at our auction and found a major problem that had been overlooked during the cataloging process, we wanted to know about it. If a problem was brought to our attention, we double-checked. If we agreed, we made certain to amend the catalog description and notify anyone who had arranged to bid. We also put a note beside the object so anyone viewing it onsite knew about the updated report on the item. My goal was to create the greatest amount of confidence for potential absentee bidders. The guarantee and how we handled problems went a long way to developing the confidence and following that evolved over the years.”

At about the time Jim decided to step back from the decoy business, he had begun to get involved with selling firearms. The division runs two sales per year. Over the last few years, Julia’s rare firearms division has grossed between $30 million and $40 million annually and has become the firm’s largest division. Jim’s comments on the success of that division will appear in a future article.

Jim’s approach to the auction business differs from that of many of his competitors. In the mid-1980s, he hired Paul LePage, a business consultant who is now Maine’s governor, to structure his business so it would run more like a corporation. Jim says, “I followed his advice. I was the company’s president but each major division had a head assisted by an administrative staff. By setting up a chain of command and corporate structure, I created a situation in which the business was not totally dependent upon me. If something happened to me and I was out for six months, the business could continue to run smoothly.”

Having been a teacher, the affable auctioneer knows how to command a crowd. If the audience becomes listless or inattentive, Jim resorts to a fast hammer or alters the volume of his voice. On at least one occasion, he tossed a damaged piece into the trash to wake up bidders.

Jim admits that there was a good deal of trial and error. He notes, “Eventually, as I changed my approach, transitioned to better trained department heads and brought in more expert consultants, things began to change. For the past 18 years, the business prospered, doing well for consignors, buyers and auctioneer alike.”

He also credits some of his success to his seller’s commission schedule. “I created a sliding-scale commission rate based on the average sales price per lot consigned, or ASPPLC. As the ASPPLC of goods consigned decreased, my commission rate increased. On the other hand, as the ASPPLC increased, my commission rate decreased all the way down to zero percent. So, if a client had a great collection or group of fine items worth a considerable amount of money, whose ASPPLC was reasonably high, they could get it sold for nothing. About ten years ago, we began to market this commission structure for all departments. The offer of the zero percent rate plus the sliding scale commission attracted an increasing number of high-value consignments. The average sale price per lot of our firearms division and most of our other divisions was either the highest or one of the highest in the industry for that specific category.”

A few years ago, Jim and his wife, Sandy, had begun to think about how they might handle the business going forward. Jim says, “I still loved the business and hoped that I would continue, as my father did, to the age of 89. In 2012, Mark Ford sold his share of a jewelry company he had been involved with. I had known Mark for nearly 25 years and respected his business acumen. We discussed structuring my company for the future and Mark joined us as CEO. After about four and half years, we had gotten to the point where Mark was running most of the business when Sandy was diagnosed with brain cancer in November 2016. The day after Sandy’s diagnosis, I basically went home and spent my time caring for her. The business was in great hands and I could do exactly what I wanted to do, which was to devote my entire attention to my wife.

He continues, “One day I received a call from a friendly competitor, Dan Morphy. During the course of a conversation about my wife and her health, he asked if I would consider selling my business. I had sold Dan my toy and advertising division in 2015 and I respected him. I thought about it for a while and, after a couple more discussions, I shared with Dan that if I could accomplish three goals, I would consider selling. First, the sale amount had to be enough to take care of me and my wife for the rest of our lives. Second, I wanted to be certain that I generated enough from the sale so that I could give any employee who did not receive a good job with Morphy’s a severance pay equivalent to a year’s salary. Finally, if I were to sell my business or merge with another company, I really hoped the new company would continue the commission structure, guarantee, etc. Dan was agreeable to all these things. It was as simple as that. We cut a deal and I merged my business with the Morphy Auction Company. Once we have completed our last auction, we will close the operations in Fairfield and I will sell the facilities. I won’t be conducting auctions for myself, although I may continue to buy and sell things.”

Jim says he is happy that the company he worked so hard to build is going to an individual who shares his enterprising approach to the auction business. He notes, “I feel the business is in fine hands. I believe Dan Morphy and his team will continue to provide a great level of service to consignors.”

The maestro of the Maine admits to feeling a tad wistful about dropping the gavel on his long, exemplary career at the helm of James D. Julia Auctioneers, noting, “I will miss the people, the collections and the excitement of my own auctions.”

It is a safe bet that Jim Julia will be missed, as well.

James D. Julia’s final sale in Fairfield, Maine, is planned for March 21-23. For information, visit www.jamesdjulia.com. A list of Morphy Auctions’ upcoming sales may be found at www.morphyauctions.com.

Rick Russack, an Antiques and the Arts Weekly contributing editor, is a retired books dealer. He created and maintains three websites devoted to the history of New Hampshire, where he resides.