“Still Life with Flowers (Tulips),” circa 1925–30. Oil on canvas, 24 by 31 inches. Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University; Morton and Marie Bradley Memorial Collection. —Kevin Montague photo

By Arlene Nichols and Cynthia Roznoy

STONY BROOK, N.Y. – When Jane Peterson (1876-1965) graduated from Elgin High School in Illinois in 1894 she had already identified a course of study and had a notion of a career. In 1893, she took aptitude tests at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago that pointed in an artistic direction. While there, Peterson would have seen the then avant-garde paintings by American Impressionists, including Childe Hassam and Edmund Tarbell. Most persuasive, however, were the exhibits at the Woman’s Building, which featured women’s fine arts, crafts and industrial products in a Hall of Honor.

Also exhibiting in the Woman’s Building were female students and alumnae from Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. Pratt offered strong support for women and Peterson felt an immediate affinity with the school. As well, the lure of New York City, already recognized as the center of the American art world, could not be denied. Seeking social mobility, experience of the world and interaction with exciting people, Peterson put Elgin behind her, moving to New York to attend Pratt Institute.

She became a dedicated student and, even with her limited funds, managed to survive in the unfamiliar city. Peterson augmented those funds by giving painting lessons to other students. She was a gifted artist even in those early days, but painted in a limited color palette and in an academic style.

During this period, Peterson met several art patrons who attended the annual student exhibitions at Pratt. One, Alexander Hudnut, became a lifelong friend and eventually shaped her future. He funded her first trip to England and Europe enabling her to continue her studies with renowned artists of the time.

When Peterson left the United States in 1907 she was Jennie C. (for Christine) Peterson, a Scandinavian Midwesterner building a career as an art teacher in New York and Baltimore. When she returned to the United States in 1909 to supervise the hanging of her first solo show, she was, jubilantly, Jane Peterson, artist. Peterson carried home from Europe a large selection of paintings from which to choose among for this exhibition, presented at Boston’s St Botolph Club.

The favorable review she earned from the Christian Science Monitor marked the beginning of the artist’s long exhibiting career and set the pattern for her way of life, which was marked by extensive, adventuresome travel followed by successful exhibitions upon her return to the United States.

The materials donated by Peterson biographer J. Jonathan Joseph to the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, offer fascinating anecdotes of Peterson’s encounters as a world traveler. Still, the best testament to Peterson’s experiences in Europe, North Africa and Turkey are the pictures she painted.

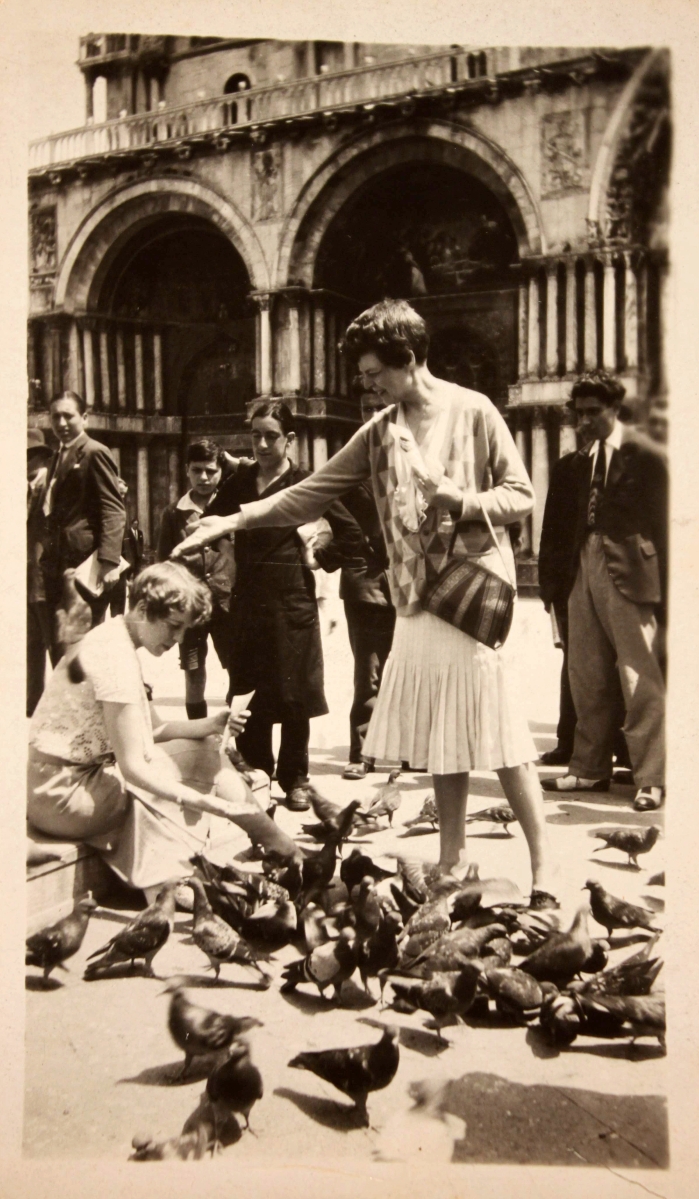

Peterson’s experiences in Europe at the end of the first decade of the Twentieth Century set the pattern for the European trips she made regularly until the outbreak of World War I and frequently in the following decades. The picturesque locales that she chose to paint reflected the favored locations of artists of her generation. Her work is celebratory, reflecting the palpable delight she experienced in having the opportunity to paint.

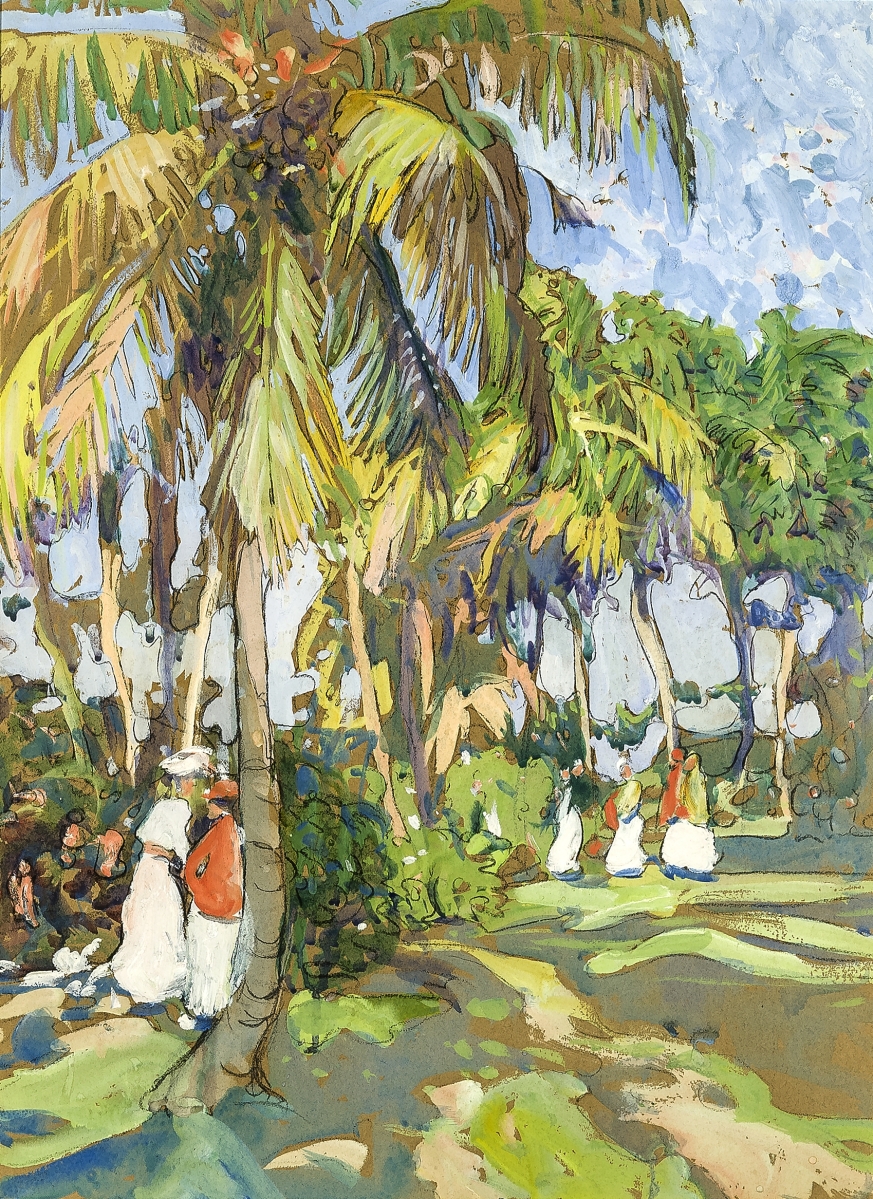

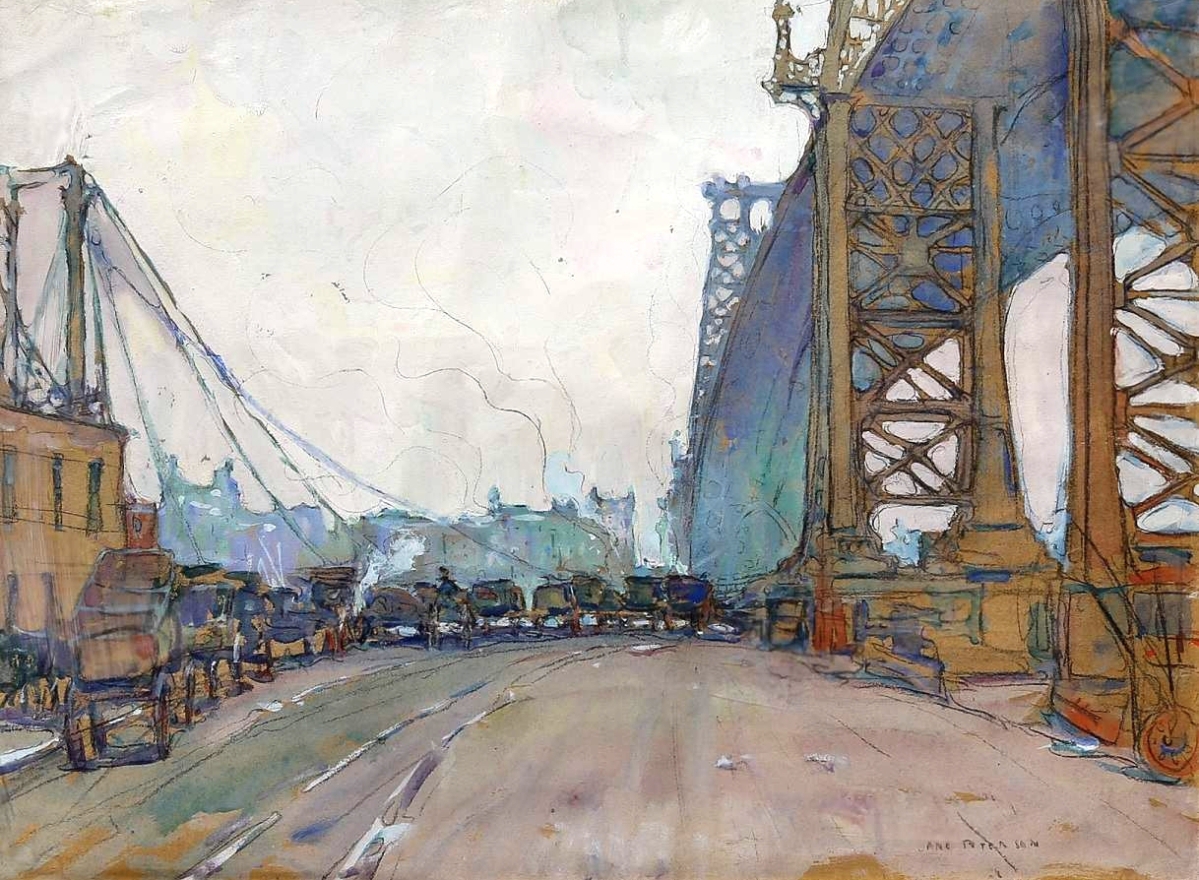

Peterson’s European scenes received positive critical reaction and established her in the public’s mind as a professional artist. In the second decade of the century, Peterson worked hard to establish herself in New York. She traveled, taught and took an active role in arts organizations. As World War I began to break in Europe, Peterson’s trips there were put on hold. Beginning in 1915, Peterson lived at Sherwood Studios, 58 West 57th Street, the first apartment house built specifically for artists. From this midtown setting Peterson would cover the city, painting its streets, monuments and celebrations.

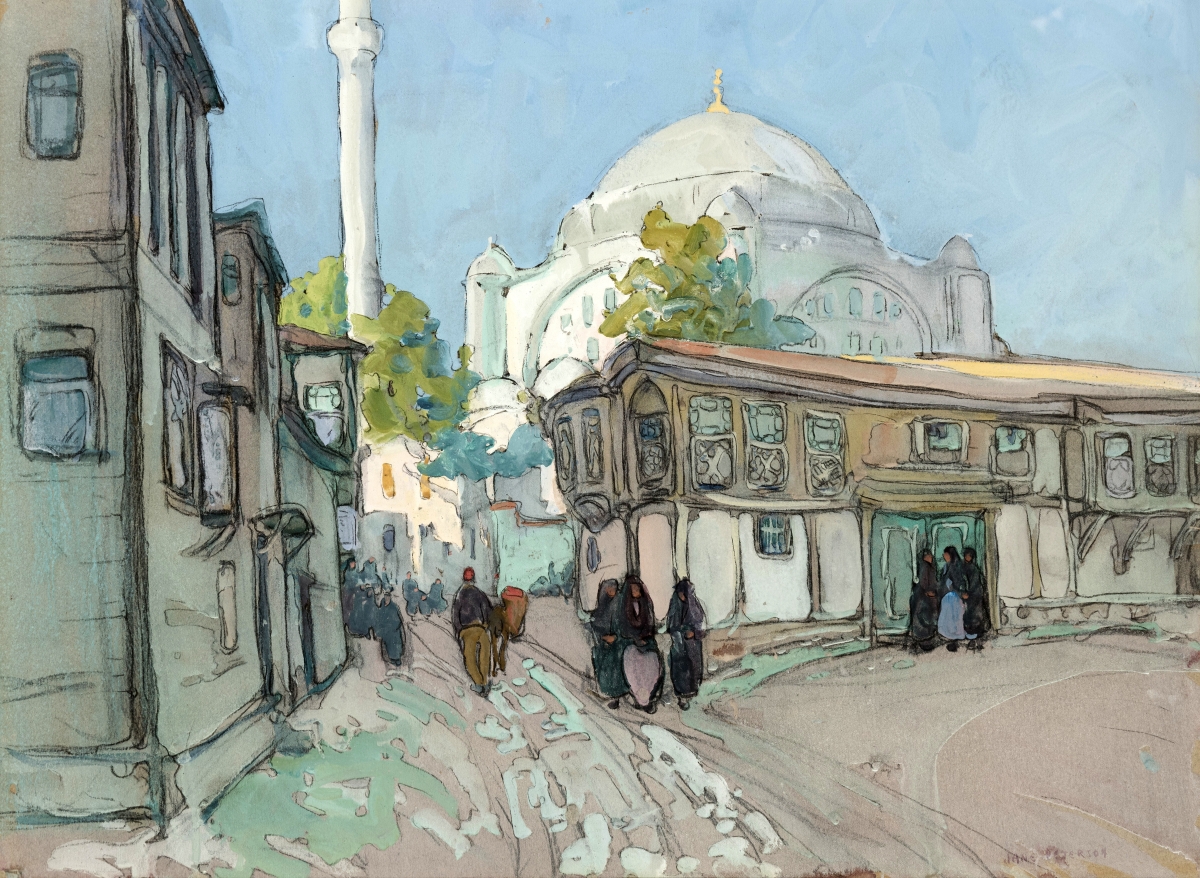

When World War I ended, Peterson’s penchant for travel was no longer throttled back. In the summer of 1924, she decided to go to Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey. The context of that trip was far more fraught than her 1910 visits to North Africa and Egypt, when, armed only with a Baedeker’s guide book, a traveler could experience all the exoticism of a world accessible to Western currencies.

“The Accused and Her Dog (Woman with Umbrella),” undated. Oil on board, 16¾ by 12¼ inches. Collection of Dominique Riviere. Photo courtesy Doyle New York.

Back in New York in late 1924, Peterson resumed her friendship with Moritz B. Philipp. Peterson’s longtime patron Hudnut had introduced her to Abby and Moritz B. Philipp a few years earlier. The group shared a love for opera, art and world travel. Moritz was recognized as a patron of music and literature, a scholar of Latin and Greek and a pillar of New York society. Abby, mother of their two children, died in 1922. Philipp and Peterson maintained their warm relationship and, in 1925, Philipp asked her to marry him. Peterson was then 49, Philipp was in his late 70s, a point not missed in a brief article about the wedding to appear in The New York Times. But in 1925, Peterson was also well-recognized – she was celebrated as one of the city’s foremost painters; in some circles she was better known than he, as attested in a society article printed in the Norfolk Dispatch with the headline, “Retired Lawyer emerges as Husband of Noted Artist.” This relationship of equals attests to Peterson’s success.

Philipp’s wealth allowed the couple a lavish lifestyle. In 1926, Philipp, determined to move from the home at 11 East 57th Street, purchased a five-story house on Fifth Avenue, across from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Though New York remained her home, the city scenes for which Peterson had been known for were no longer part of her subject matter. Her husband did not support the Ash Can style. As Peterson biographer Joseph has identified, Philipp was a conventional man of the period who insisted his wife’s artmaking would continue only if it did not interfere with his established routine. Philipp’s preferred subject matter was apparently flowers – a subject befitting a genteel society woman. The married Peterson acquiesced, focusing on painting the subjects that would become synonymous with her name in later years.

Peterson was not totally dismayed with the restricted subject choice. She had loved flowers since a child when she worked alongside her mother in the garden. As well, she had enjoyed and benefited from the patronage of Louis Comfort Tiffany, who offered artist residencies at Laurelton Hall, his Oyster Bay, N.Y., estate. Her painting of a garden at Laurelton Hall, “Lure of the Butterfly,” was exhibited in the Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Connecticut Academy of Fine Arts in Hartford where it won the Charles Noel Flagg prize for best painting. With its brightly colored depiction of a young woman in pursuit of an elusive butterfly, this composition demonstrates the degree to which Peterson had developed her distinctive style.

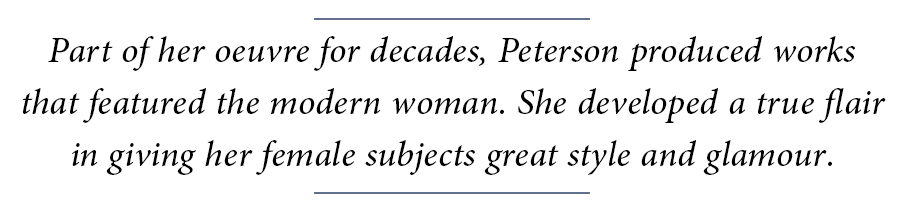

Part of her oeuvre for decades, Peterson produced works that featured the modern woman. She developed a true flair in giving her female subjects great style and glamour. In “Accused with Her Dog (Woman with Umbrella),” a modern dressed woman directly gazes toward the viewer.

Peterson once told the press that “no matter where I go I always want to come back to New York.” But she had other home cities that were close to her heart. Gloucester, Mass., an art colony at Cape Ann, was among them. The Philipp country home, Rocky Hill, was in nearby Ipswich, Mass. Some of Peterson’s finest painting was done at Gloucester, colorful pictures filled with the light of day. She utilized a bright, prismatic palette and strong outline in robustly structured compositions. Peterson delighted in the picturesque town and reveled in capturing the rippling effects of light on its coast.

Peterson had to cut back on exhibition participation during her marriage. In 1929, she exhibited only in the National Academy Annual and its watercolor show, probably because Phillipp was in poor health. That September he underwent abdominal surgery from which he did not recover. He died two days later. Newspapers made much of Philipp’s estate, which, according to The New York Times, was appraised at more than $10 million. Peterson received a life annuity, a trust fund, and the Fifth Avenue and Ipswich homes with all furnishings, collections and personal effects. The will also provided for the construction of a studio at Ipswich for her use.

“Tiffany’s Garden,” circa 1913. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 28 by 22 inches. Long Island Museum of American Art, History and Carriages, Stony Brook, N.Y.

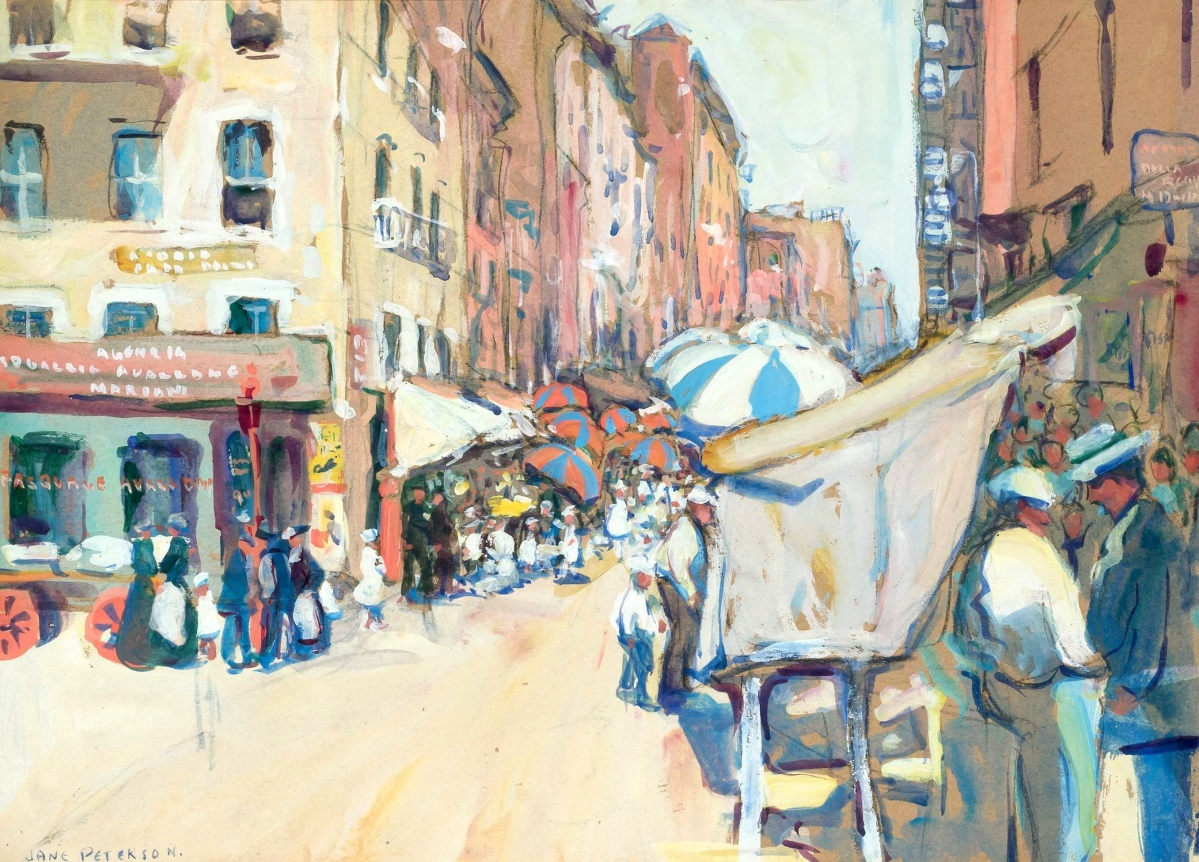

Free to resume her independent ways, Peterson returned to Europe in the 1930s. By 1938, however, global travel began to pale for Peterson, then in her early 60s. Returning from an extended trip through France, Spain and Egypt that year, she told a reporter for the New York Sun that she had “seen most of the fascinating crannies between the poles,” but “today, Palm Beach is the garden spot of the world.” Peterson spent many 1930s and 1940s winters in that winter retreat and tourist destination.

Peterson’s first visit to Florida was probably in late 1915 or early 1916, given that she exhibited a painting of Palm Beach in the 1916 Annual Exhibition of the New York Water Color Club. Searching for summer in the winter seems to have appealed to her because she soon became a regular visitor to that city. Several years later, while in Palm Beach for several weeks, Peterson was among several artists – including Cecelia Beaux, Robert Henri and John Sargent – who organized an exhibition for a local charity to support a hospital. It was reportedly a great success with many stylish patrons. This mingling of art and society was very much the Palm Beach style, one Peterson found immensely to her liking.

Floridian landscapes and flora and fauna scenes created in the 1930s are among the most Modernist of Peterson’s art. Sea grapes in red and green are the glory of one of Peterson’s late paintings. They fill the canvas from edge to edge with curvaceous flat leaves, spiky veins and spots of berries. Peterson has zoomed in, to provide a minimal distance between viewer and subject.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Peterson maintained her busy social life, moving between New York, Palm Beach and Ipswich. Exhibition opportunities lessened as critical acceptance and popular endorsement of 1950s pure abstraction left her behind. Age and illness also claimed a cost. The admired and talented woman, once an active society matron, was no longer remarked upon in the social columns. By 1960, when she retired to her niece’s home in Kansas, Peterson was lost to the contemporary art world. She spent the last five years of her life there until her death at age 88 in 1965. There was a two-day auction at Rocky Hill the following year. The contents of the house were sold, as well as more than 1,500 of her paintings. By that time, Peterson’s art was virtually forgotten.

Beginning in the 1970s, Peterson’s work came under scrutiny as an interest in Modernism and women’s art converged. However, it was not until 1981 that Peterson’s life and art became better known. In that year, J. Jonathan Joseph published the first monograph, joining Peterson’s biography and artistry. Beginning in the 1990s Peterson was represented in group exhibitions. Until 2017 and this exhibition, no museum had arranged an assessment of her work. “Jane Peterson: At Home and Abroad” presents more than 80 works revealing how Peterson’s vibrant paintings provided a vital link between the Impressionist and Expressionist movements in American art. It reveals an independent woman, an American artist seeing the world through fresh eyes and interpreting it for an American audience.

“Jane Peterson: At Home and Abroad” was organized by the Mattatuck Museum, where it was on view through January 28. Following its close at the Long Island Museum on April 22, it travels to the Columbia (S.C.) Museum of Art May 13-July 22, and to the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, N.Y., August 5-October 12.

The Long Island Museum is at 1200 Route 25A in Stony Brook. For information, 631-751-0066 or www.longislandmuseum.org.

Arlene Katz Nichols is senior researcher at Hirschl & Adler Galleries in New York City.

Cynthia Roznoy is curator of the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury, Conn.