“The Virgin and Apostle,” early 1170s. Limestone, 24½ by 28 by 13 inches. Terra Sancta Museum, Basilica of the Annunciation, Nazareth. Photo ©Marie-Armelle Beaulieu /Custodia Terræ Sanctæ

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY — Just before “Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven” opened to the public at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in September, I was standing in the rain at the corner of 55th Street and Sixth Avenue, trying to hail a cab uptown. The United Nations General Assembly was convening. Delegations from around the globe packed the city’s hotels. Turkey had taken over the Peninsula. Brazil was across Fifth Avenue at the St Regis. Ill-tempered in their ill-fitting suits, secret service agents from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe were everywhere. Midtown traffic was snarled.

Diplomacy. Terrorism. Power. Standing in line outside the Metropolitan Museum, still in the rain, I held my umbrella over a wet couple who turned out to be French. “Trop tard,” the woman said, thanking me. Too late. And then I was in the museum’s Great Hall, taking in the sprays of fresh flowers in the gigantic vases and feeling the susurrant waves of dozens of languages echoing off the ribbed vaults and domed arches of this cathedral of art. It struck me then: New York is a modern Jerusalem.

On view through January 8, “Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven” examines the myriad cultural traditions and aesthetic influences that enriched and enlivened the medieval city. The unprecedented display assembles nearly 200 objects from 60 sources. More than four-dozen key loans come from Jerusalem’s diverse religious communities, some of which have never before shared their treasures outside their walls.

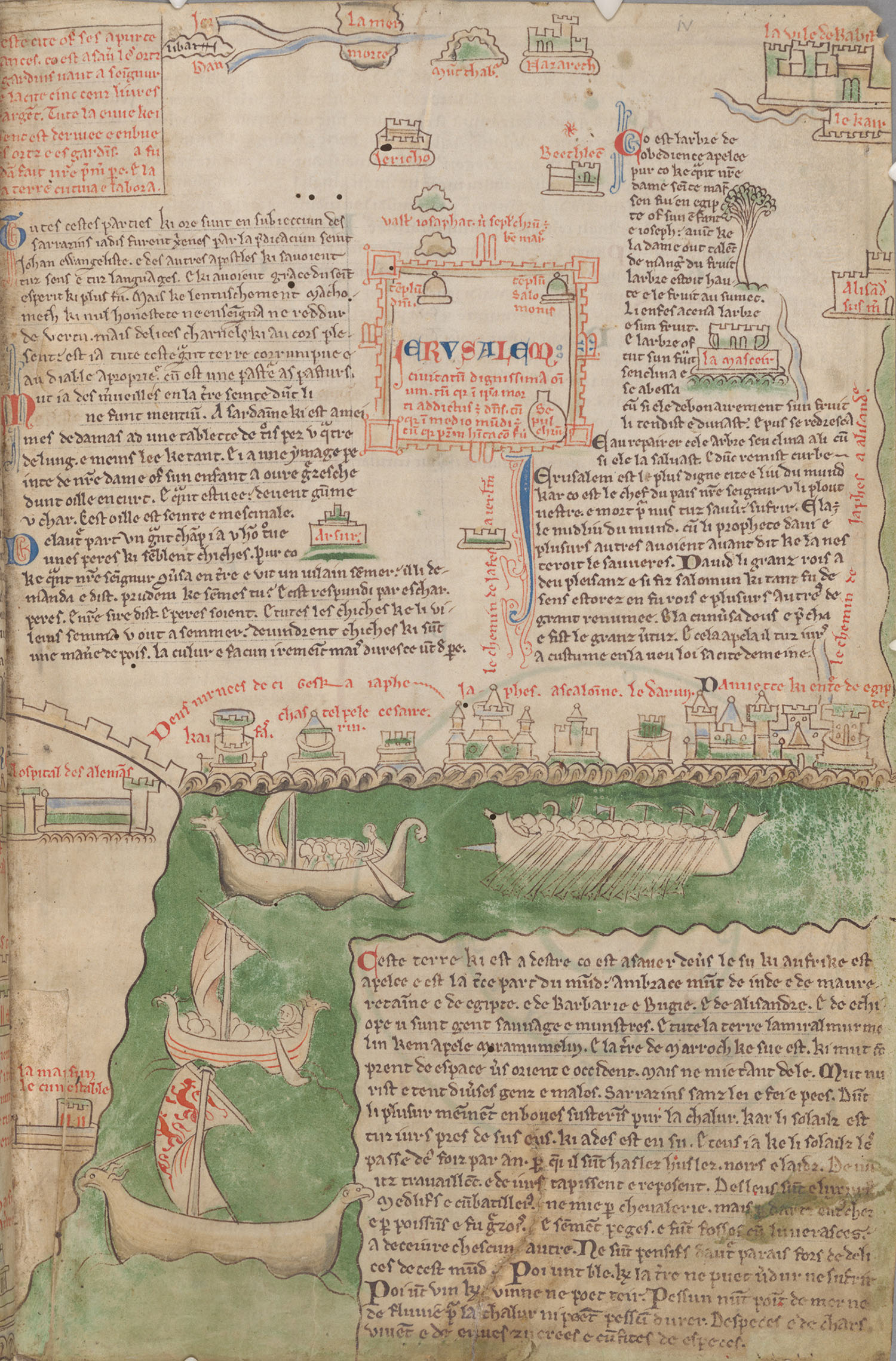

The first work in the exhibition and catalog is British monk Matthew Paris’s “Map of the Holy Land,” written and illustrated sometime between 1240 and 1253. The plan is packed with “can’t miss” places to visit and things to see. One place to avoid is the stronghold of “The Old Man of the Mountain,” where the dreaded Assassin sect of Islam, the stuff of Crusaders’ nightmares, was headquartered. Paris’s map calls to mind the guidebooks that tourists around Manhattan unfold, jab at, argue over. That the city of Acre looms larger in Paris’s Jerusalem testifies to the truth that cartography is politics. In Paris’s time, Acre was the largest Crusader-held city in the Holy Land, while Jerusalem was in Muslim hands. That Paris never left Britain, that this remarkable parchment is the work of an eager armchair traveler, makes it all the more arresting.

The first work in the exhibition and catalog is British monk Matthew Paris’s “Map of the Holy Land,” written and illustrated sometime between 1240 and 1253. The plan is packed with “can’t miss” places to visit and things to see. One place to avoid is the stronghold of “The Old Man of the Mountain,” where the dreaded Assassin sect of Islam, the stuff of Crusaders’ nightmares, was headquartered. Paris’s map calls to mind the guidebooks that tourists around Manhattan unfold, jab at, argue over. That the city of Acre looms larger in Paris’s Jerusalem testifies to the truth that cartography is politics. In Paris’s time, Acre was the largest Crusader-held city in the Holy Land, while Jerusalem was in Muslim hands. That Paris never left Britain, that this remarkable parchment is the work of an eager armchair traveler, makes it all the more arresting.

“Jerusalem, 1000–1400” makes a number of salient points, but the essence of the show is this: the battles of the Crusades punctuated long stretches of time when Jerusalem enjoyed relative peace, coexistence, exchanges of ideas and trade, and — to use a word that has gone out of fashion lately — tolerance.

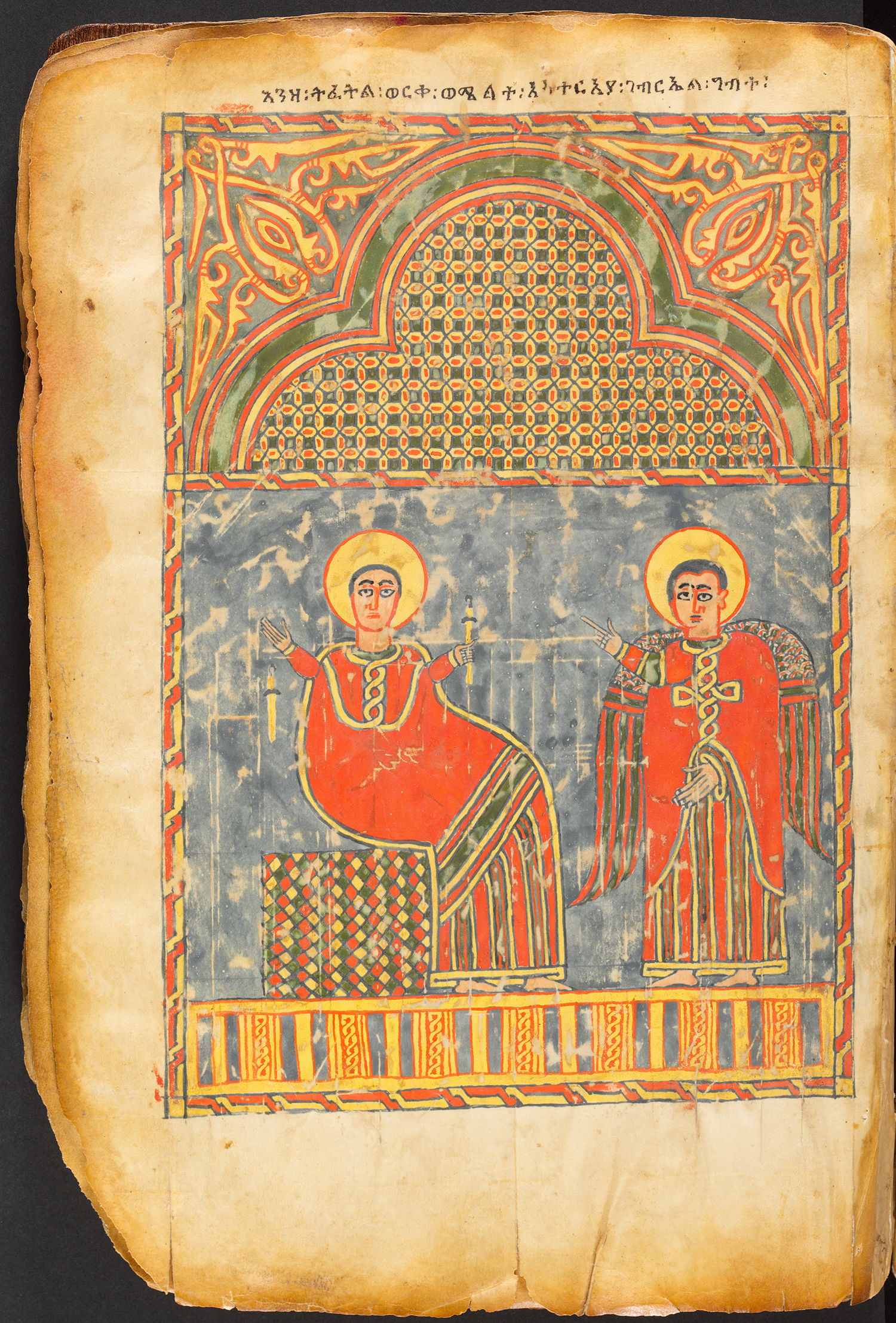

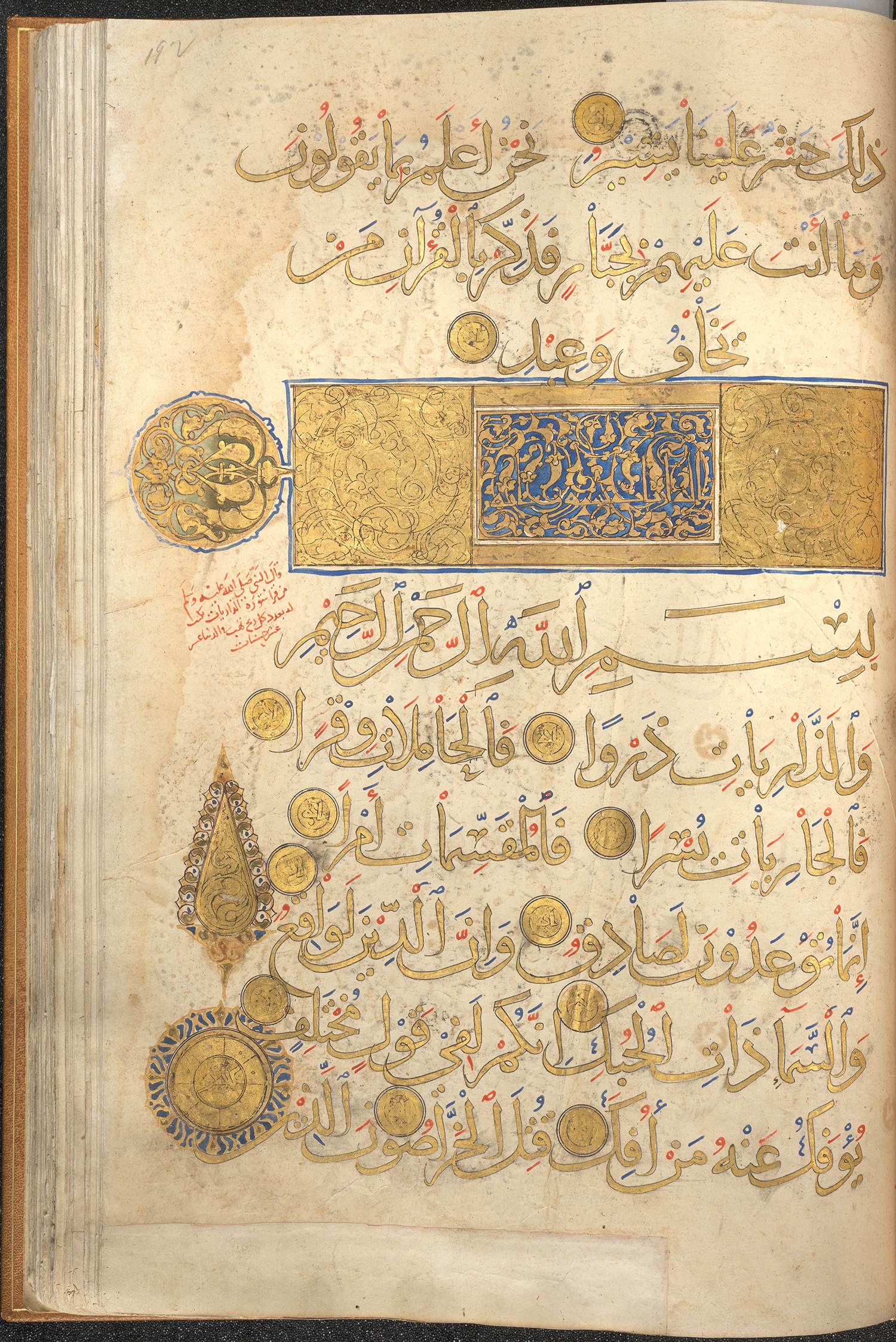

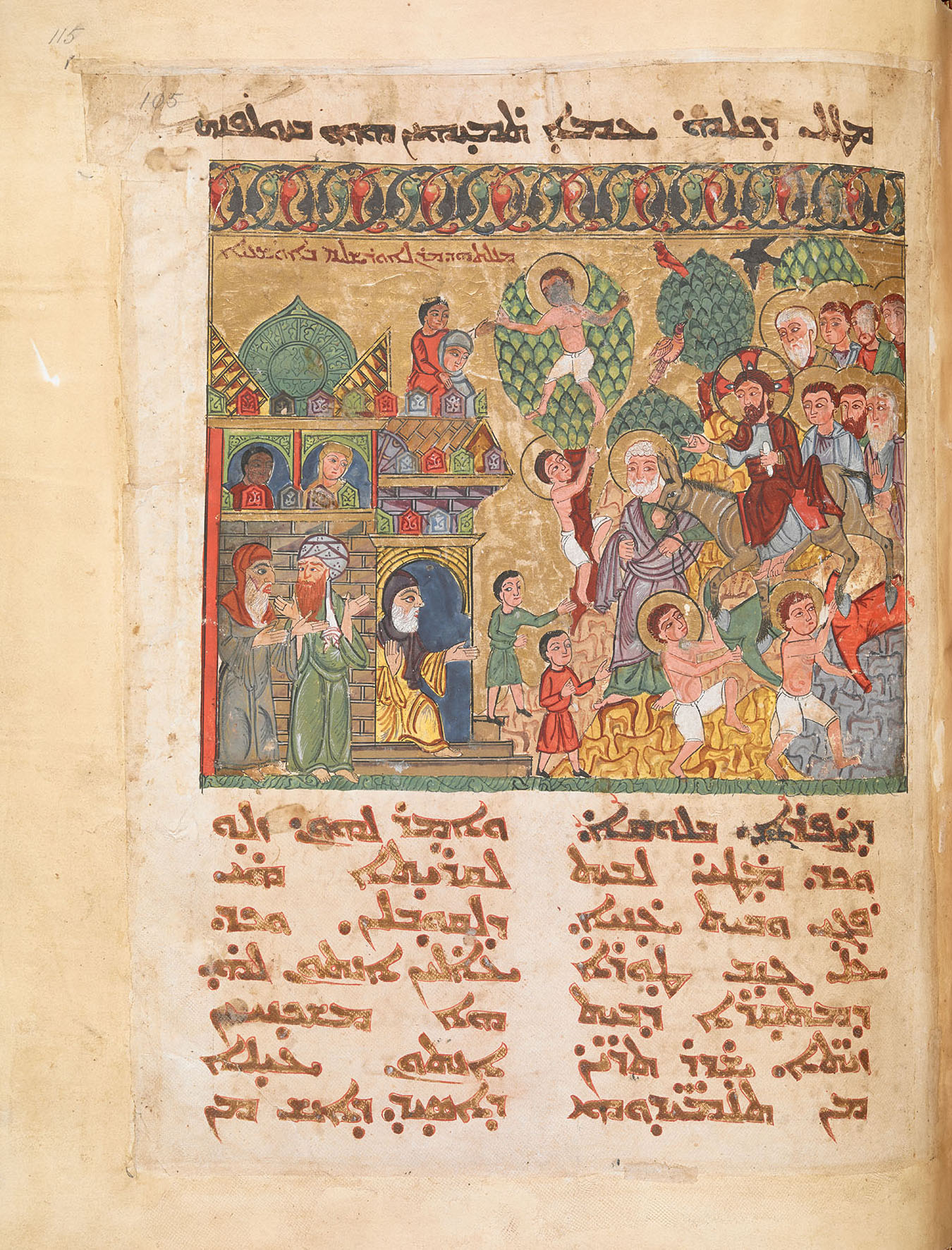

Illuminated, gilt-adorned Gospels, Qur’ans and Torahs, as well as orders of service, letters, prayer books and theological commentaries in Latin, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew and medieval Ethiopian Ge’ez, speak to one another across the galleries, the din of their dialogue and disputation unquenched across the centuries.

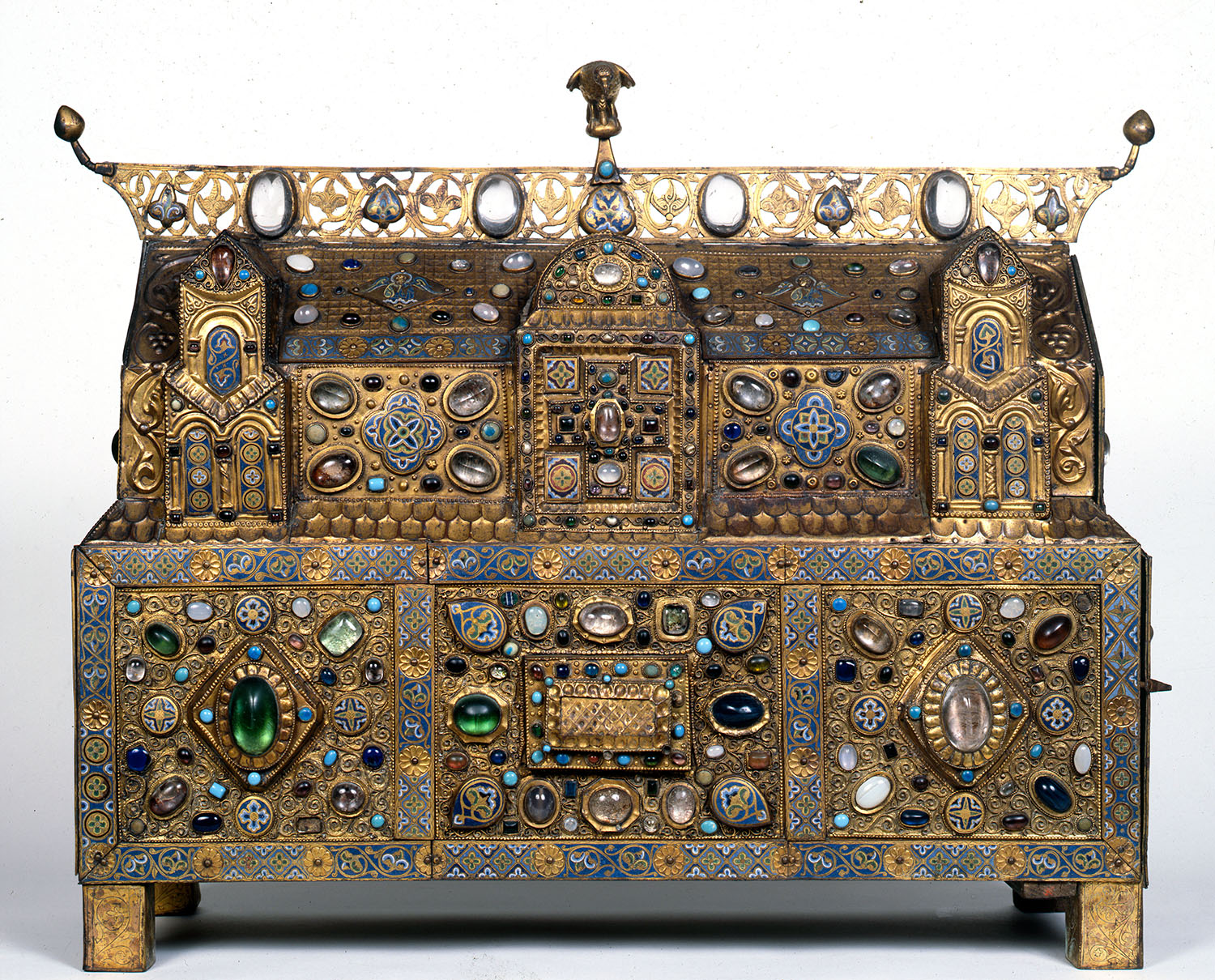

Chasse of Ambazac, from the Treasury of Grandmont, Limoges, circa 1180-90. Gilded copper, champlevé enamel, rock crystal, semiprecious stones, faience and glass; 23 by 31 by 10¼ inches. Mairie d ‘Ambazac. Image ©Region Aquitaine-Limousin-Poitou-Charentes, Service de l’Inventaire et du Patrimoine Culturel; photo Philippe Rivière

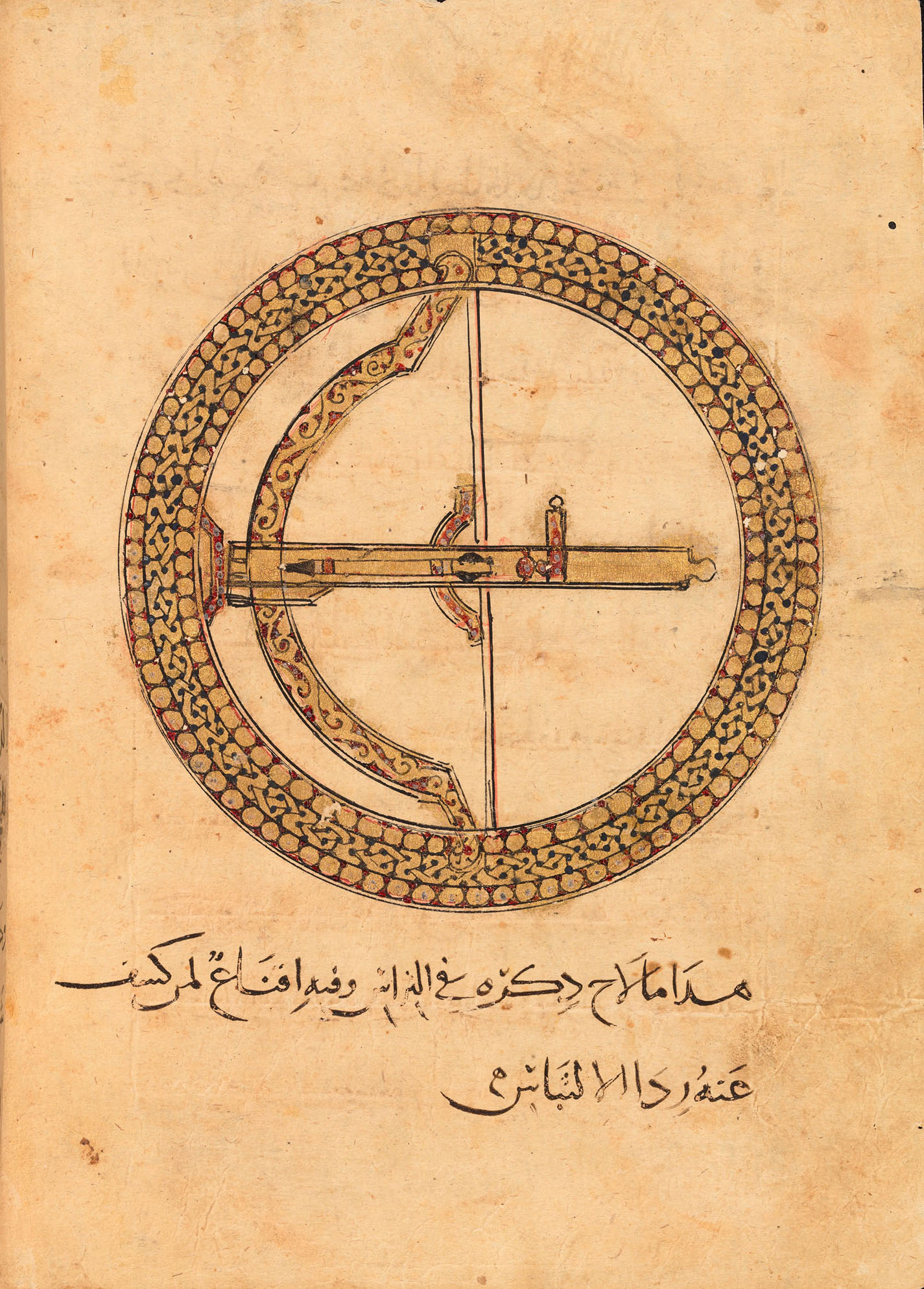

I am drawn to the objects that reflect points of cross-cultural contact, the intersections, clashes, moments of coexistence and even, on occasion, understanding. Shared interest in mathematics, navigation, astrology and astronomy shine through in three extraordinary Andalusian planispheric astrolabes. One has numbers and letters in Arabic, one in Hebrew, one in Latin. Each, tellingly, features the city of Jerusalem as a lodestone point on its complex metal map.

A celestial globe that belonged to Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil evokes his correspondence with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and the consequences of their communication. Scholarly exchange formed the basis for mutual respect. As a result, the emperor and the sultan managed within a matter of months and without bloodshed to forge a temporary truce. The Treaty of Jaffa of 1229 was an imperfect agreement, but it opened the Holy City to the subjects of both rulers for a decade.

Some of the objects in the exhibition are amazing survivals. Having been expelled with many Jews from Moorish Spain, the great Jewish physician, philosopher and arbiter of Talmudic law Maimonides (1135–1204) visited Jerusalem before becoming the spiritual leader of the Jews in Egypt. His “Plan of the Temple in Jerusalem,” a project twice ruined, and his poignant letter asking for donations to ransom Jews captured by the Crusaders, both in his own hand, are a tactile connection to this period and to the tightrope that Jews had to walk between Christians and Muslims.

Detail, “The Archangel Israfil,” from The Wonders of Creation and Oddities of Existence (‘Aja’ib al-Makhluqat) by al-Qazwini (1202–1283), Egypt or Syria, late Fourteenth to early Fifteenth Century. Opaque watercolor and ink on paper, 15 by 9 inches. British Museum, London

Balancing the ornate wedding rings, pilgrims’ certificates and souvenir glasses — tourists, right? — are the reminders of the bloody episodes of total war that Jerusalem endured. But among the captured swords, hung near the carved stone effigy of “A Knight of the d-Aluye Family,” not far from the magnificent Treatise of Armor that belonged to Saladin, one small, simple, anonymous watercolor leaps out. In “Scene of Carnage,” pierced and severed limbs and heads are strewn about. The eyes of some are open, others are closed. Even the horse at bottom left has paid a savage price. Friend cannot be distinguished from foe. The almost journalistic view is peaceful, but only in the silence of death. Jerusalem, the beginning, is also the eschatological end.

As if to symbolize the elusiveness of harmony, the goblet of Charlemagne, with its name and story straight out of Indiana Jones, sits there, Syrian enameled glass atop a French gilded-silver foot. The goblet has assumed mythic status. According to tradition, it represents Charlemagne’s gift to the Abbey of the Magdalene at Châteaudun, to which it once belonged — an extraordinary feat given that Charlemagne lived some 400 years before the work was made. Its inscription, likely not understood by its first European owner, is a formulaic expression of good wishes.

In short videos of Jerusalem as it is today, various scholars and residents describe the delicate ballet between and within the four quarters of the Old City: Christian, Jewish, Muslim and Armenian. In one, a proud Kurdish tailor who supplies stunning ceremonial robes to clerics of all religions laughs, relishing the fact that people of different faiths are often compelled to engage with one another in his shop. His shop brings to mind mercantile New York City. To do business here, it is best to get along.

Like the catalog that accompanied “Pergamon,” the exhibition in the Met’s Tisch Galleries that preceded this one, the book Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven, edited by Barbara Drake Boehm and Melanie Holcomb,is gorgeous and scholarly while still eminently readable.

The rain let up by the time I left the museum. The traffic had not. As we inched down Fifth Avenue, I asked the driver how his week was going. “It’s a week for kings and presidents, not for the likes of us,” he answered. Back at the gallery where I work, I imagined a retrospective exhibition on New York a century from now. Would curators unearth evidence of a new beginning, of a collective will to right humanity’s wayward course?

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For further information, 212-535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org.

Jim Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City. A playwright and author, he writes frequently about the arts.