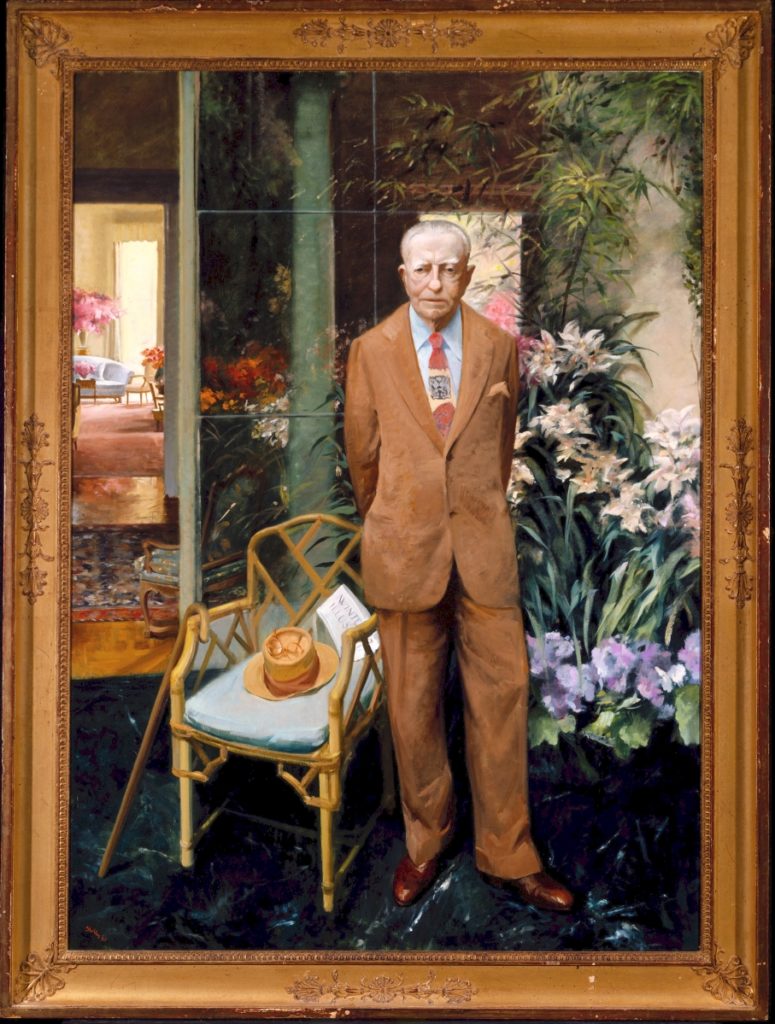

Jacqueline Kennedy asked Henry Francis du Pont to chair her Fine Arts Committee, charged with helping select and acquire historically appropriate furnishings for the White House. He is seen here, a year before his death, in his conservatory in this 1968 oil on canvas portrait by Aaron Shikler. Winterthur Museum, photo Jim Schneck.

By Laura Beach

WINTERTHUR, DEL. – In a fragmented media landscape riven by political rancor, it is hard to imagine an event as unifying as Jacqueline Kennedy’s televised White House tour, broadcast by three major networks in February 1962 and ultimately viewed by 80 million people. The San Francisco Chronicle hailed it as “a splendid patriotic hour,” writing that America had “reason to be proud…of a new First Lady who has revitalized an old house.”

According to Elaine Rice Bachmann, Maryland State Archivist and guest curator of “Jacqueline Kennedy and Henry Francis du Pont: From Winterthur to the White House,” the fashionable First Lady with a finishing-school voice not only stimulated interest in collecting and preservation, but also introduced a wide swathe of the American public to Winterthur Museum and its founder, Henry Francis du Pont, for the first time. The story of their collaboration is told as never before in a colorful new exhibition on view at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library through January 8.

Jacqueline Kennedy in the Du Pont Dining Room at Winterthur, May 8, 1961. Winterthur Archives, photo Robert Hunt Whitten.

Surprised that no one had yet mined the museum’s rich archives, Bachmann began researching her topic as a graduate student at Winterthur in the early 1990s. Former Winterthur curator John A.H. Sweeney, who had a ringside view of the restoration, introduced her to fellow graduate student James Archer Abbott, an authority on the French decorating firm Maison Jansen, whose role in the White House project was decisive, if, for political reasons, largely hidden from the public. Merging their expertise, Bachmann and Abbott collaborated on the 1997 book Designing Camelot: The Kennedy White House Restoration, a substantially updated version of which was reissued in 2021 by the White House Historical Association, founded by Jacqueline Kennedy to formalize accessions and collections management.

“In many ways, both private and public, my mother straddled two eras, the one when women stayed home and had few opinions that differed from their husband’s, and the coming age when women broke free and became independent. She lived fully in both,” Caroline Kennedy writes in the book’s foreword, observing with pride that her mother – 31 years old, with a 3-year-old and a newborn baby when her husband took office – “transformed the White House into one of the nation’s most important museums of American art, decorative arts and history, and created a stage for the greatest performing artists of the day.”

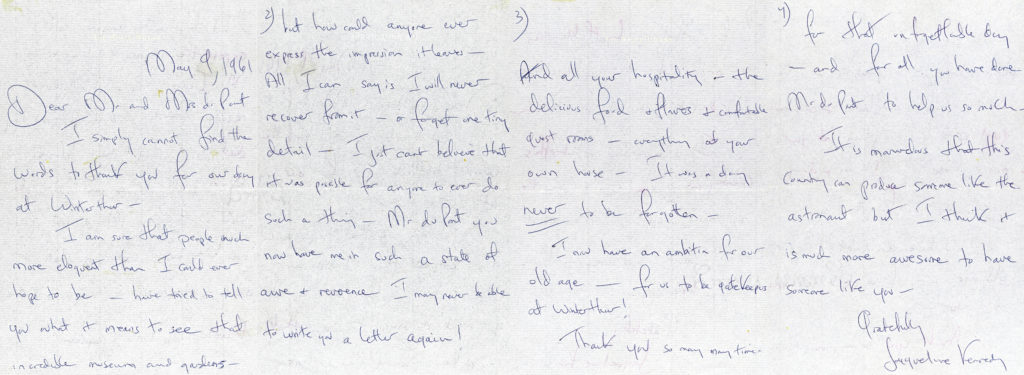

The day after her Winterthur visit in May 1961, the First Lady wrote du Pont thanking him for the lunch and tour. Her four-page, handwritten note concluded, “It is marvelous that this country can produce someone like the astronaut but I think it is much more awesome to have someone like you.” Winterthur Archives.

The First Lady began refurbishing the White House within days of moving in. “I know we’re out of money…but never mind…we’re going to find some way to get real antiques into this house,” she wrote after she and society decorator Sister Parish, hired by the Kennedys to redo the family’s private quarters, exhausted sums set aside by Congress. As Sweeney told Bachmann, after Winterthur declined to loan antiques to the White House, someone – possibly museum director Charles F. Montgomery, though others have been mentioned – suggested making du Pont chairman of the Fine Arts Committee, charged with soliciting donations of appropriate furnishings for the mansion.

In his role as committee chair, du Pont toured the White House for the first time in April 1961. Keen that the new furnishing plan be historically plausible – few original White House decorations survive – du Pont asked two distinguished historians to draft a guiding statement of principal. “Everything in the White House must have a reason for being there. It would be sacrilege merely to redecorate it – a word I hate. It must be restored…,” Kennedy wrote, even if privately she took a softer line.

Eager, as du Pont put it, for Kennedy to see that “you can have a really swell house with American furniture,” he hosted the First Lady for lunch and a tour of Winterthur on May 8, 1961. Among the exhibition’s treasures is a series of rediscovered snapshots – du Pont nixed press coverage of the visit -including one showing Kennedy, gazing heavenward, on Winterthur’s famous Montmorenci staircase. Progress was such that by September 1961, Kennedy was able to share her plans for the revitalized White House with Life magazine. CBS approached her the following month regarding the televised tour, filmed at the White House, January 13-15, 1962.

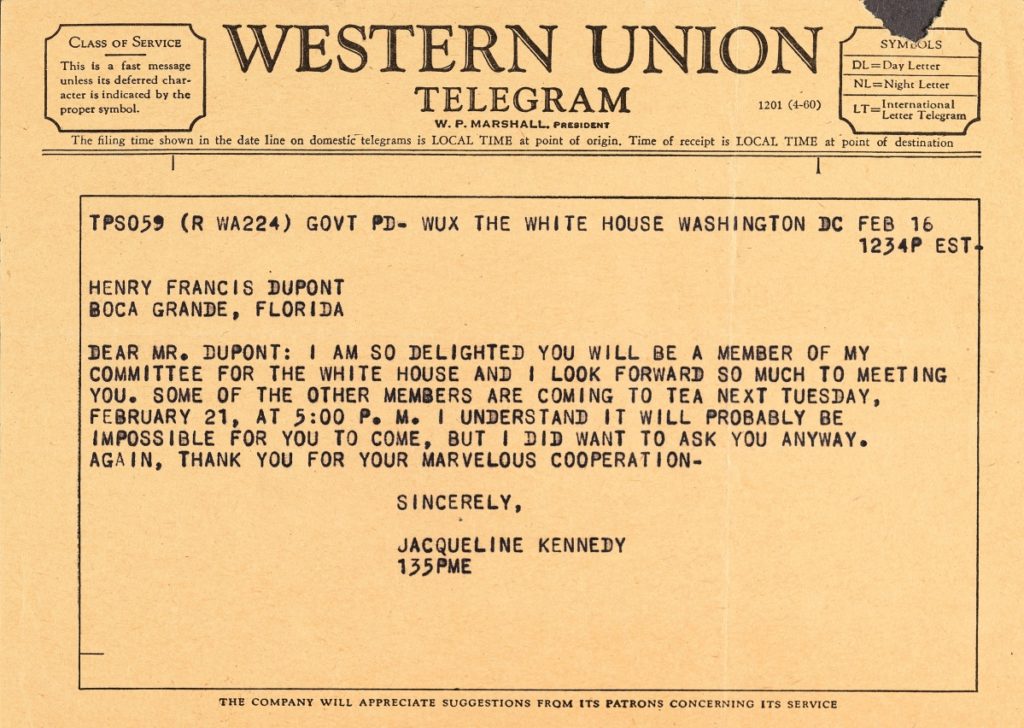

The first correspondence between Jacqueline Kennedy and Henry Francis du Pont is this telegram of February 16, 1961, acknowledging his commitment to chair the Fine Arts Committee. Du Pont was at his winter home in Florida at the time. Winterthur Archives.

The rest of the story is well known. President Kennedy was assassinated the following year. Du Pont visited the White House periodically as an advisor to the Johnson administration, which honored the spirit of the project. Jacqueline Kennedy returned to her former home only once, during the Nixon years. In her last letter to du Pont as First Lady, she wrote, “I told you in the very beginning that I never wanted any contribution from you but your heart, and your time – and, you have given of those so much more than one ever could have hoped for.”

The show opens in the South Gallery with the First Lady herself, represented by a mannequin wearing a red dress replicating the American-made copy of the Christian Dior design Mrs Kennedy wore for her televised tour. Trained on the figure are broadcast cameras borrowed from the National Museum of Broadcasting. Purchased from CBS, video clips of the tour play nearby.

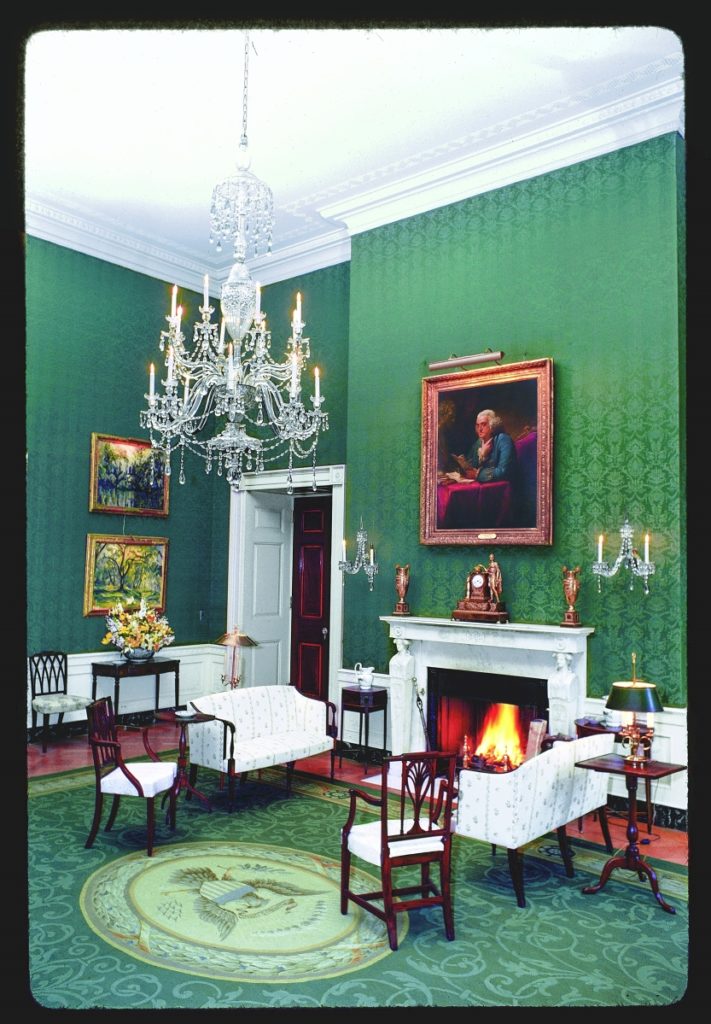

After sketching the project’s origins, progress and principal participants, the exhibition proceeds to a series of vignettes representing the evolution of the White House’s three main reception rooms. Du Pont’s influence was most pronounced in the Green Room, conceived as a Federal parlor. He wrote Kennedy, “As I see it, the room is a charming, intimate little room, and everything should be kept in low scale.”

Du Pont and his chauffeur, Dana Taylor, escorted Jacqueline Kennedy to a waiting car during her May 8, 1961, visit to Winterthur. Winterthur Archives, photo Robert Hunt Whitten.

For the Red Room, debate centered on whether to feature American Empire (as Classical design was then called), Phyfe or French Empire furnishings. Du Pont favored Phyfe, but Empire – French and American – won out. Attempting to allay du Pont’s concerns, Kennedy wrote, “…as long as it has the eagle, it doesn’t matter if it’s French.”

The Blue Room, designed around rediscovered pieces of furniture from a suite ordered for the room from French cabinetmaker Pierre-Antoine Bellangé by President James Monroe in 1817, was more controversial still. Paid for by Charles and Jayne Wrightsman – the latter a Kennedy confidante, committee member and Jansen client – it was entirely the work of Jansen president Stéphane Boudin. Now executive director of Wright’s Ferry Mansion in Pennsylvania, Abbott says, “Boudin was the true arranger of all the rooms, the supplier of most period textile remnants for copying, and the colorist – the tastemaker who redefined the familiar and not-so-familiar White House rooms as stylish, historically inspired backdrops for the Kennedy presidency.”

Bachmann asked the textile manufacturer Scalamandré to reach deep into its archives to retrieve samples of the documentary fabrics it recreated for the Kennedy White House. The curator worked with Natalie Larson, a specialist in historic textile design and fabrication, and fabric painter Lucretia Moroni of Fatto a Mano to recreate the look and feel of the sumptuous treatments made to match the White House’s palatial scale. Swayed by Boudin, the First Lady chose unconventional shades of the Truman White House colors, selecting, among others, a mossy green verging on chartreuse; a hot, pinky-cerise red; and, contrarily, white walls for the Blue Room.

Conceived as a Federal parlor, the Green Room most illustrates du Pont’s influence as chairman of the Fine Arts Committee. In this photograph of March 1962, David Martin’s 1767 portrait of Benjamin Franklin hangs above a marble mantel purchased by James Monroe for the State Dining Room in 1817. Courtesy White House Historical Association.

Behind the scenes, the Fine Arts Committee was never as influential as the White House encouraged the public to believe, nor was du Pont ever thoroughly in charge. As Kennedy herself wrote him in 1962, “…we are a lot of cooks now and the broth gets rather complicated.” But according to Bachmann – whose sources include both Sweeney and du Pont’s daughter Ruth Lord – the rivalry between du Pont and Boudin has been overstated.

“Mrs Kennedy manipulated a great many people, and du Pont was one. But far from resenting Boudin, he was enormously honored by the appointment and embraced his role as chairman. The First Lady validated his life’s work. Her televised tour was a material culture lesson for the country, bringing the concept of Winterthur’s period rooms to a wide audience,” Bachmann says.

Of the many individuals the curator reconsiders, one who puzzles is Lorraine Waxman Pearce. The Winterthur graduate became the White House’s first curator upon du Pont’s recommendation. Though she approached her work with professional vigor, her brief White House tenure was fraught. Mrs Kennedy openly preferred her self-effacing successor, William Voss Elder III. Pearce resigned after completing the first White House guidebook, now in its 25th edition, in 1962.

Henry Francis du Pont and his wife, Ruth, in the Red Room of the White House, April 14, 1964. Left is a gueridon by Charles-Honoré Lannuier. Du Pont later regretted not buying this table when it was offered to him. Winterthur Archives.

Jacqueline Kennedy insisted on privacy during and after her White House years. Bachmann explains, “She abhorred the press but realized if she was going to get the story of the restoration out there, it had to be her narrative. Hugh Sidey’s September 1961 article in Life thus became the seminal piece of contemporaneous reporting on the project.”

The fiercely controlling First Lady was not able to suppress all controversy, some of it driven by Washington Post reporter Maxine Cheshire, who wheedled sensitive details out of Jansen and Scalamandré. Unable to track down the infamous lady’s writing desk initially accepted for the Green Room but later found to be a late Nineteenth Century reproduction, the curator borrowed a comparable replica. Bachmann also revisits a contretemps involving the Diplomatic Reception Room, where the acquisition of historic wallpaper by Zuber et Cie drew criticism for its cost. Du Pont defended the $12,500 purchase of the 1834 “Views of North America” panels from antiques dealer Peter Hill.

Refurbished by subsequent occupants, little of Jacqueline Kennedy’s decoration survives. What lingers is her respect for the past and the mechanisms she created to safeguard it. As Caroline Kennedy explains, “My mother believed that living in the White House was the greatest privilege one could have and worked hard to be worthy of the house.”

Jacqueline Kennedy turns to speak with H.F. du Pont in the Green Room of the White House on December 5, 1961, during a meeting of the Paintings Committee. James W. Fosburgh, seated next to the First Lady, chaired the committee. Robert Knudsen, White House Photographs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum; courtesy White House Historical Association.

Bachmann observes, “The great legacy of what Mr du Pont and Mrs Kennedy did was to establish a permanent collection. Every administration makes choices about what it places on public view, but no longer are furniture or works of art simply discarded.” Kennedy’s Fine Arts Committee survives as the Committee for the Preservation of the White House. As listed in the new edition of Designing Camelot, gifts to the White House have continued, swelling under the Nixon and Ford administrations, slowing during the Obama and Trump years. Kennedy’s project set a standard still strived for by governor’s mansions nationwide.

Abbott reflects, “As the public face of the often highly scrutinized Kennedy restoration of the White House, du Pont validated any and all changes Mrs Kennedy introduced, and, clearly, the White House project afforded du Pont and his beloved Winterthur national recognition as the authority on period American decorative arts.”

“Piecing history together is difficult, even when it is only 60 years removed. Personal insights do much to enhance the archival record,” says the curator, grateful for the support she received over the years from Sweeney, Pearce and others. One of the few direct witnesses to the project still alive is Charles F. Hummel, who chased down Secret Service agents after the First Lady left her handbag at Winterthur. In a video loop playing in the galleries, Bachmann may be heard interviewing the Winterthur curator emeritus, proof that Camelot endures, if glimmeringly.

Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library is at 5105 Kennett Pike. For information, 800-448-3883 or www.winterthur.org.