This case piece, ornamented in a traditional Punjabi style, bears the inscriptions “NLMATULLA” (referring to the decorator) and “J. L. KIPLING ESQUIRE.” It was shown at the 1888 Glasgow International Exhibition. Wedding chest by Niamut Ulla of Delhi, circa 1888. Wood, paint and brass.

Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

NEW YORK CITY – “This is a colorful and multilayered, not monochromatic, exhibition. The public will see a richness in Kipling’s achievement.” Martin Levy, the London-based dealer in furniture and works of art and Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century design expert, warmly praised “John Lockwood Kipling: Arts & Crafts in the Punjab and London,” which graces New York’s Bard Graduate Center (BGC) Gallery September 15-January 7. A supporter of this exhibition as well as other initiatives at BGC, Levy characterized Kipling (1837-1911) as “ripe for reappraisal as an educator, designer and proselytizer of Indian arts.”

Julius Bryant, keeper of word and image at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, and Susan Weber, the founder and director of the Bard Graduate Center, have co-curated the first major initiative to explore the life and artistic contributions of John Lockwood Kipling. In conversation, Weber told how the initial idea for mounting an exhibition on Kipling was Bryant’s. It grew from his involvement, some years before, with the reinstallation of the Indian-inspired dining room at Queen Victoria’s residence Osborne, a space designed in part by Kipling. Weber and Bryant also co-edited the nearly 600-page catalog containing 17 essays and an array of sumptuous illustrations befitting its subject.

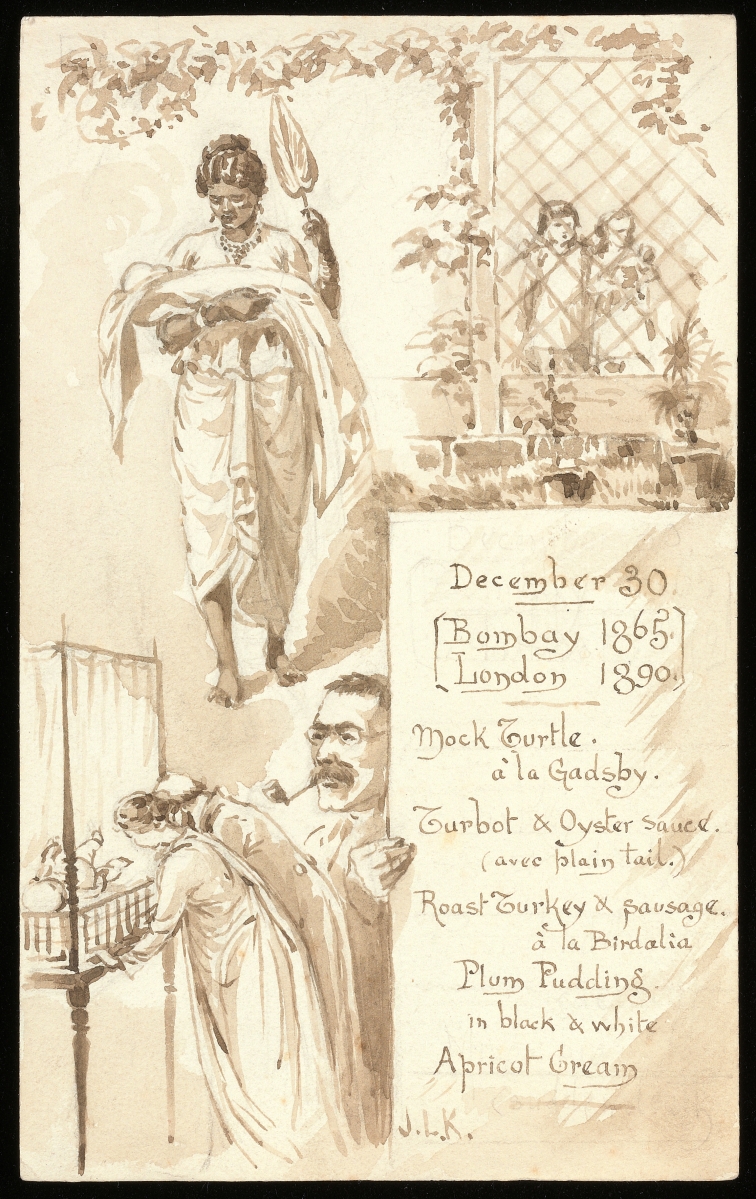

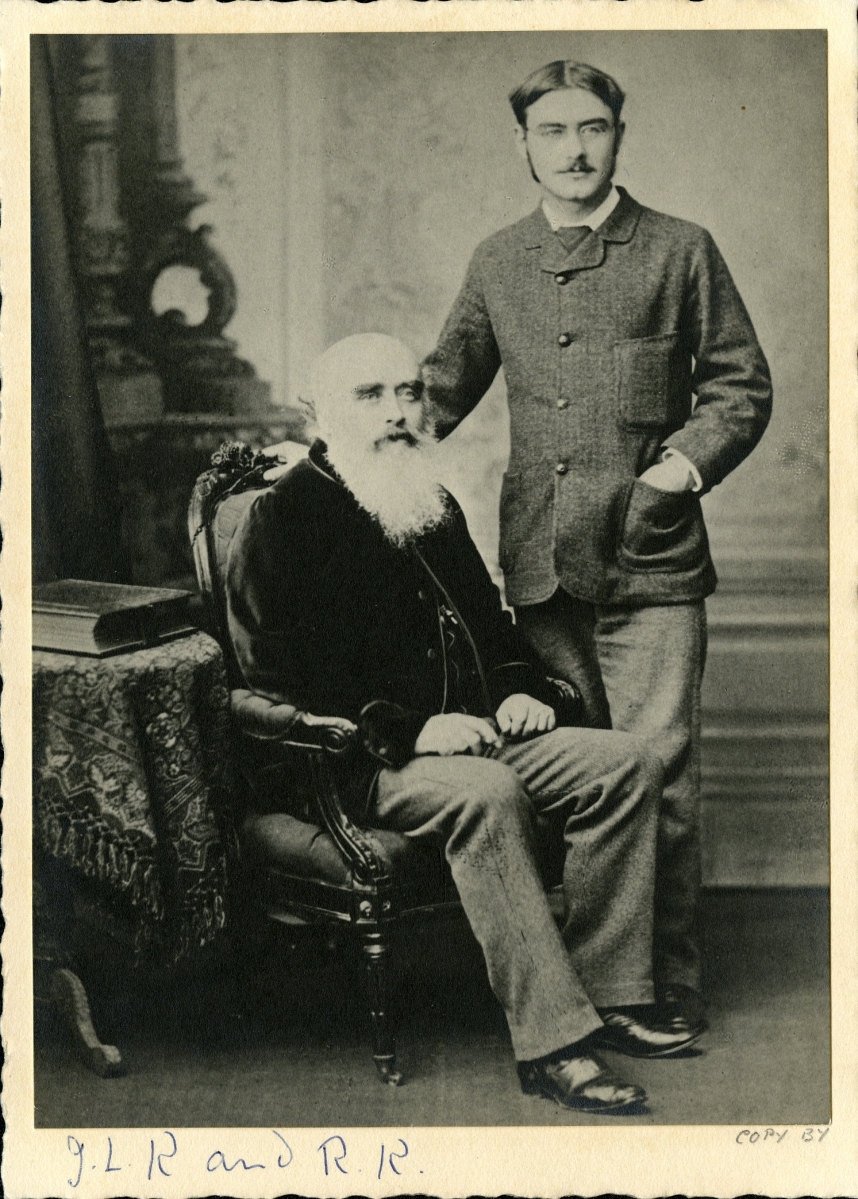

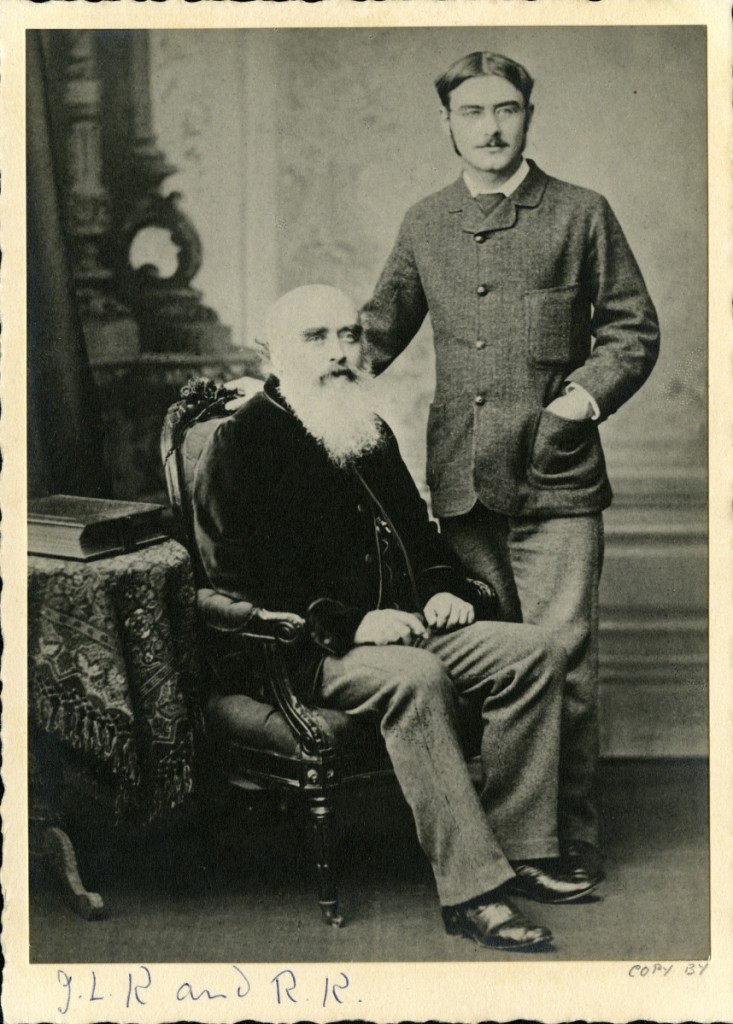

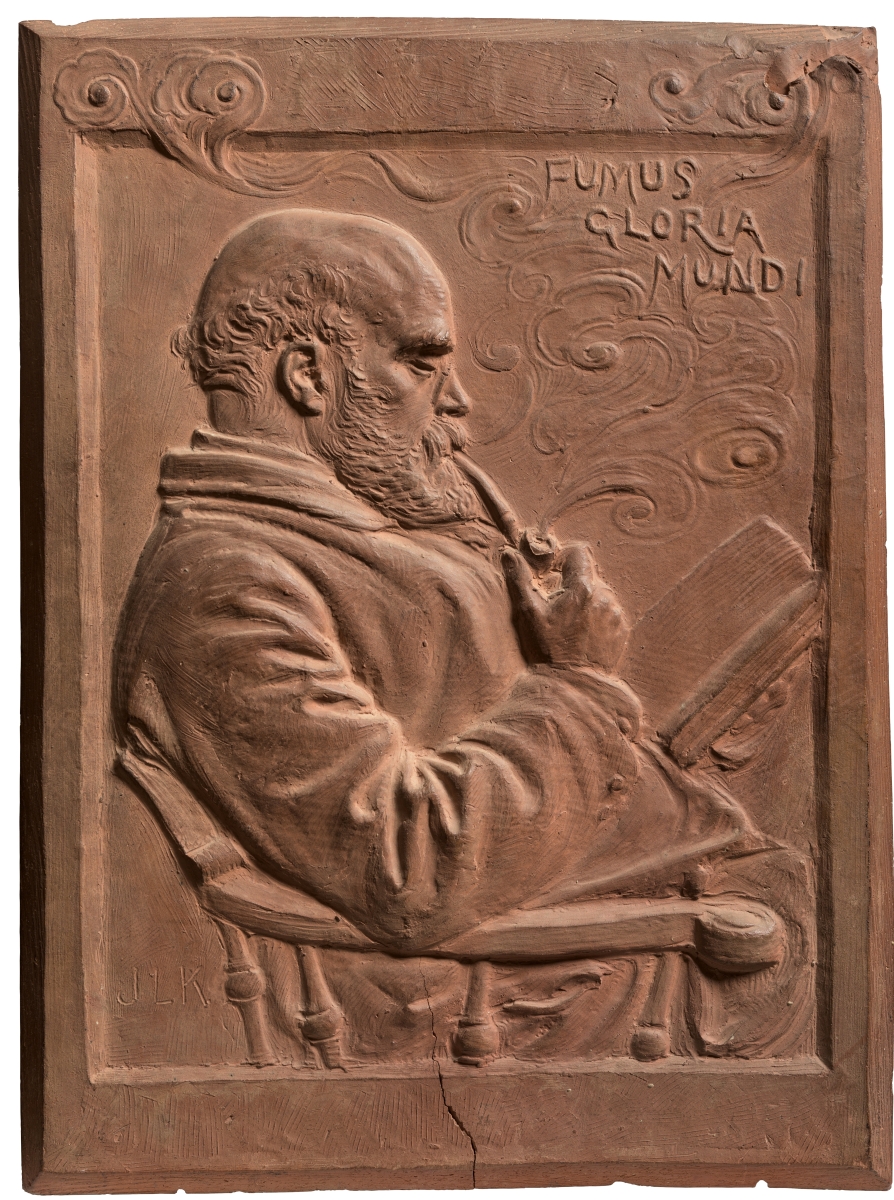

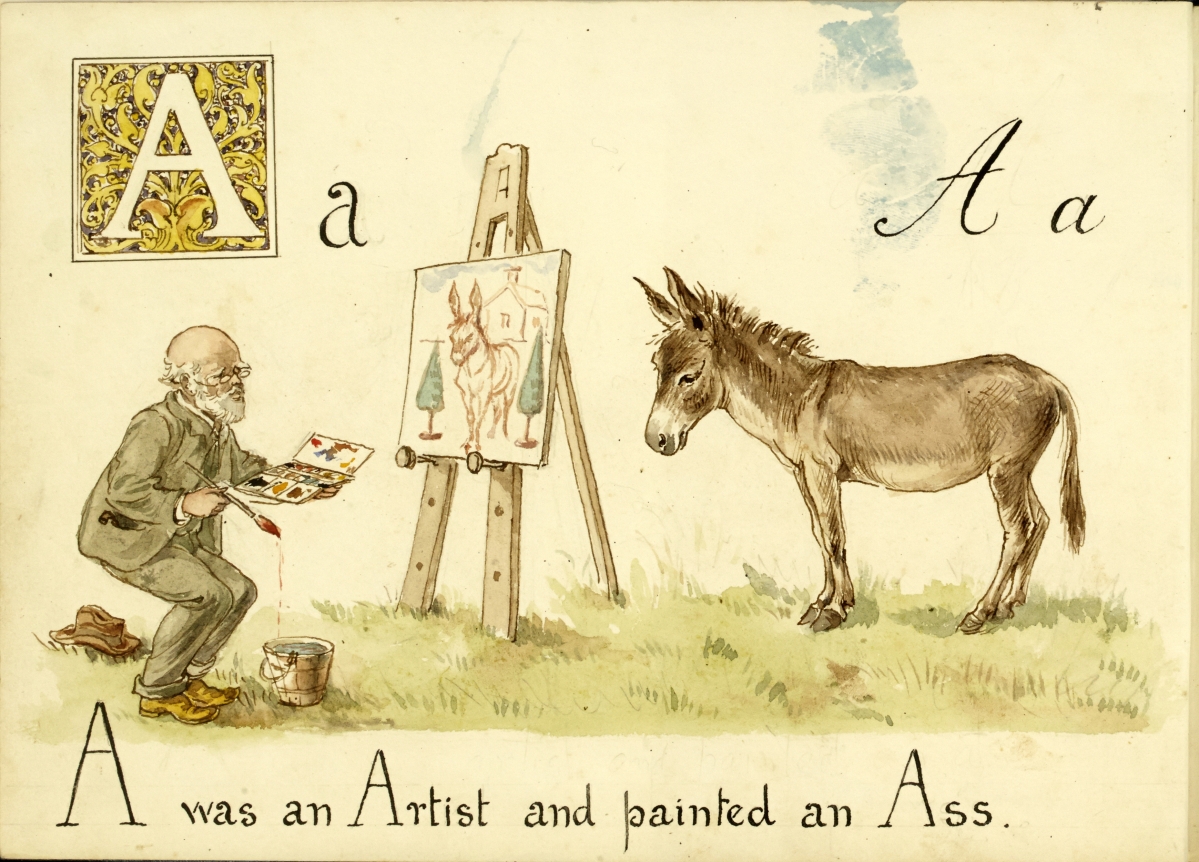

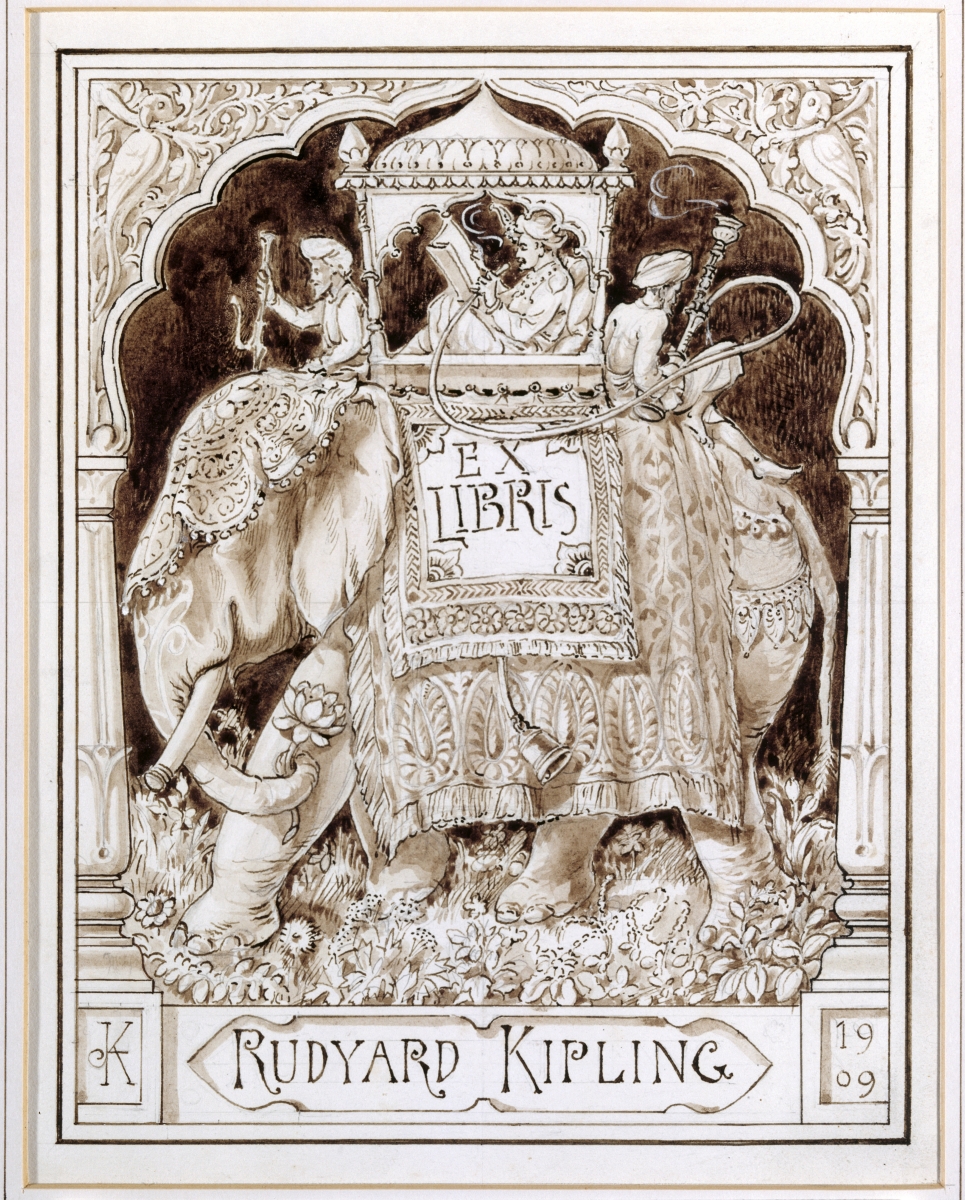

It is only a bit of an exaggeration to say that the genius Lockwood Kipling pursued some sort of artistic endeavor nearly every waking hour. Perhaps best known as the father of the writer John Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), he demonstrated prowess as a ceramicist, sculptor, arts educator, crafts promoter, curator, exhibition designer, architectural preservationist, editor, art commentator, journalist, illustrator and interior designer.

This son of a Methodist minister started his career as an apprentice at the pottery manufacturer Pinder, Bourne & Hope in Stoke-on-Trent. He advanced to become a designer and modeler while attending local branches of national design schools. He moved to London about 1859, and there took on various jobs, including sculptor of architectural ornament at the South Kensington Museum (rechristened the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899).

This son of a Methodist minister started his career as an apprentice at the pottery manufacturer Pinder, Bourne & Hope in Stoke-on-Trent. He advanced to become a designer and modeler while attending local branches of national design schools. He moved to London about 1859, and there took on various jobs, including sculptor of architectural ornament at the South Kensington Museum (rechristened the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899).

Kipling married Alice Macdonald in 1865 and the couple traveled to Bombay (Mumbai) so he could assume the post of ceramics and architectural sculpture instructor at the Sir J.J. School of Art and Industry. During their years in this city, Lockwood and Alice became parents to surviving children John Rudyard and Alice. They both also began to work as freelance journalists at this time. In 1870, the Indian government commissioned Kipling to execute a series of drawings documenting craftspeople laboring in the North Western Provinces and in the Punjab, part of a broader fact-finding mission to ascertain the economic possibilities India offered. This journey, and others made beyond Mumbai, made him more keenly aware that Indian art was not simply Hindu art, but also encompassed Buddhist, Islamic and Sikh artistic traditions.

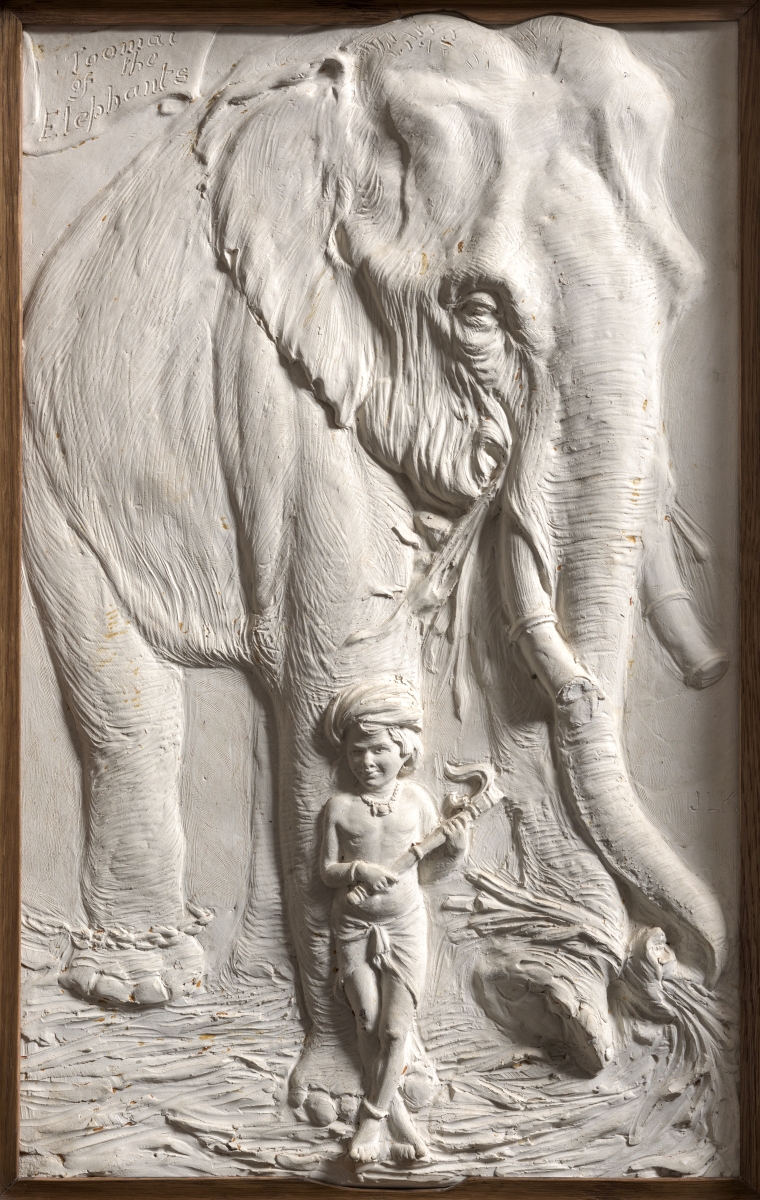

Between 1875 and 1893, Kipling served concurrently as the principal of the Mayo School of Industrial Art in the city of Lahore (now in Pakistan, but then part of India) and as the curator of the Lahore Museum. The latter position’s duties included creating displays of local crafts for expositions and exhibitions mounted in Asia and Europe. He teamed with Bhai Ram Singh (1858-1916) – an architect, designer and fine woodworker who had been an outstanding student and later master at the Mayo School – in the creation of the Indian Billiard Room for the Duke and Duchess of Connaught at Bagshot Park in Surrey (circa 1884-90), the aforementioned state dining room at Osborne on the Isle of Wight (1890-92) and building and related projects in Lahore. Kipling’s retirement in 1893 took him back to England, where he practiced the art of illustration, specializing in the India-focused books written by his son.

Through his own talents and connections, combined with those of Alice – herself a Pre-Raphaelite muse – Kipling had been received into the British Arts and Crafts coterie. Like other proponents of this movement, Kipling strove to preserve hereditary craft practices under threat from the Industrial Revolution and its swell of factory-produced goods. Weber explained that Kipling came to the realization that some of India’s crafts would have to be modified for success in the West, and so he directed students at the Mayo School to examine traditional work and then adapt it to assure market viability.

That said, Kipling’s support of Indian handicraft was not driven purely by artistic, cultural and economic considerations. He saw political benefit as well. As quoted in the catalog, the historian Peter Hoffenberg characterized Kipling and his compatriots as “confident that they were shoring up the British Raj by shoring up India’s artistic, social and political traditions: that is, their authentic India, in contrast to the India of cities, factories and machines.” Similarly, in the catalog introduction, Weber and Bryant describe how some believed that India’s traditional crafts and their associations with deep-rooted cultures and constancy could help ameliorate Britons’ horror-filled reaction to India’s Revolt of 1857-58, a violent and widespread insurrection, and ensuing resistance to Britain’s greater governmental participation and investment in India.

Kipling and the Mayo School of Industrial Art chose these ornaments, among other traditional craft objects, to represent the Punjab region at the 1888 Glasgow International Exhibition. Pair of armlets, Hazara, Punjab (now Pakistan), circa 1888. Silver and enamel. Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections.

When queried why the brilliant Victorian had not received much attention until now, Weber gave several reasons. As a public figure, Lockwood Kipling was overshadowed by his son Rudyard, an author widely read but also marked by controversy due to his politics of empire. The decades the elder Kipling spent in India, at the far reaches of the British Empire and away from England, lessened his appreciation. From a historiographic perspective, scholars have been somewhat stymied by Kipling’s wealth of proficiencies, which defy easy categorization. Weber asked rhetorically, “What to do with a polymath – a teacher, a potter, what is he?” She also declared that Kipling is not singular in his neglect. “So many people of his time are being rediscovered.”

In her catalog essay, Weber focused on Kipling as an active and in-demand exhibition curator and designer. This subject authority selected, and sometimes arranged, handcrafted objects from the Punjab and environs for international and regional display at a time when expositions were important places for public art education.

Weber pointed to objects reflective of this aspect of the multifaceted Kipling. They include a floral-painted wedding chest made at the Mayo School for the important 1888 Glasgow International Exhibition of Science, Art and Industry. She related that Glasgow, one of the centers of British manufacturing during the Nineteenth Century, was both a trading partner and a competitor of India’s. Through the Glasgow Exhibition, organizers hoped to raise funds for the establishment of a museum, school and art gallery in the city and, in fact, the wedding chest and some other objects from the Indian Pavilion became part of the founding collection of the resulting Glasgow Museum. Weber noted the historical value of these items as actual examples of the kinds of crafts Kipling wanted to highlight through the 1888 world’s fair.

Weber then turned to another “showpiece” from about the same time, but rendered in a completely different spirit, a set of dessert plates that Kipling had individually decorated and put on view at the 1881-82 Punjab Exhibition of Arts and Manufacturers. What is surprising is the subject matter, with most of the scenes mocking Indian servants and their ways. Kipling undoubtedly created his “one just can’t get good help nowadays” china-painted lament for the perceived amusement of the British expatriate community.

Weber stated that it was essential to include such challenging objects in the current exhibition to illustrate that Kipling “was sympathetic to Indian craftsmen yet he was also an agent of British imperialism. These plates with their negative underlying messages are representative of the perspective of the British ruling class during the Raj. We needed to show them to put him in his time and place.”

Until this exhibition, which premiered at the V&A earlier this year, most people knew little to nothing about Rudyard Kipling’s highly accomplished father. “John Lockwood Kipling and Rudyard Kipling,” 1882. Albumen print. Kipling Papers–Wimpole Archive, University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep.

Drawn from collections in Great Britain, Pakistan and the United States, the 250 art, artifact, library and archival treasures in the Kipling exhibition exemplify the range of the man’s creative expression as well as his professional and personal passions. Many items are on loan from the V&A, an institution remarkable for forming the first major Indian art collection in the West and for spearheading public appreciation of traditional Indian arts and crafts, according to Weber. She added that the V&A acquired a portion of the contents from the Indian Court installed at the 1851 “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.”

A few of these objects have been included in the BGC show, appropriately enough since young Kipling’s excursion to the Great Exhibition is credited with igniting his lifelong infatuation with India. Levy brought the V&A’s strong connection with the Nineteenth Century up to the present, observing, “The field is very excited that a scholar of the Victorian era, Tristram Hunt, is the new head of that institution.”

With an influence and an oeuvre spanning cultural, continental, media and academic divides, Lockwood Kipling defies traditional art-historical pigeonholing. In their analysis, Weber, Bryant and their colleagues have located and interpreted the diverse, the hybrid, the complex and the nearly forgotten. The result is a virtuoso exhibition and catalog, proof positive that there are still mind-blowing figures and collections to be resurrected by receptive and determined researchers. Martin Levy summed it up thusly, “BGC has once again rescued lost material, not for its own sake, but because it has a story to tell.”

The accompanying catalog of the same title was edited by Julius Bryant and Susan Weber and published by Bard Graduate Center Gallery and Yale University Press, 2017.

The Bard Graduate Center Gallery is at 18 West 86th Street. For more information, 212-501-3000 or www.bgc.bard.edu.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.

.jpg)

.jpg)