“Juan de Pareja” by Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, 1599-1660), 1650, oil on canvas, 32 by 27½ inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876-1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971. Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY — How do we know the name Juan de Pareja? Is it because he was a renowned painter of Seventeenth Century Spain? Or is it because he was the subject of a portrait by an even more famous painter of the same time and place? “Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from April 3 through July 16, seeks to recover the artist’s work and personal history on his own terms, with a broad look at what it meant to be Spanish, African, an artist and enslaved in what is still sometimes problematically called Spain’s “golden age.”

Famously, Juan de Pareja (circa 1608-1670) is the subject of an exceptional portrait by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), his teacher and enslaver. The portrait was purchased by the Met in 1971 from a private British collection for a “price that at the time was considered to be outrageous,” says David Pullins, the Met’s associate curator of European Paintings and the present exhibition’s co-curator, with Vanessa K. Valdés of The City College of New York. In many ways, the portrait by Velázquez provides a framework for the show — a visible document of the intersections that defined these two artists’ complex relationships with Spain and Seville, with Rome (where the portrait was painted), with art and with each other. But the exhibition does not begin there. Instead, visitors will approach the exhibition not through Velázquez’s eyes, or the eyes of the Met’s curators in the 1970s, but through the writings and photographs of renowned Afro-Puerto Rican scholar Arturo Schomburg.

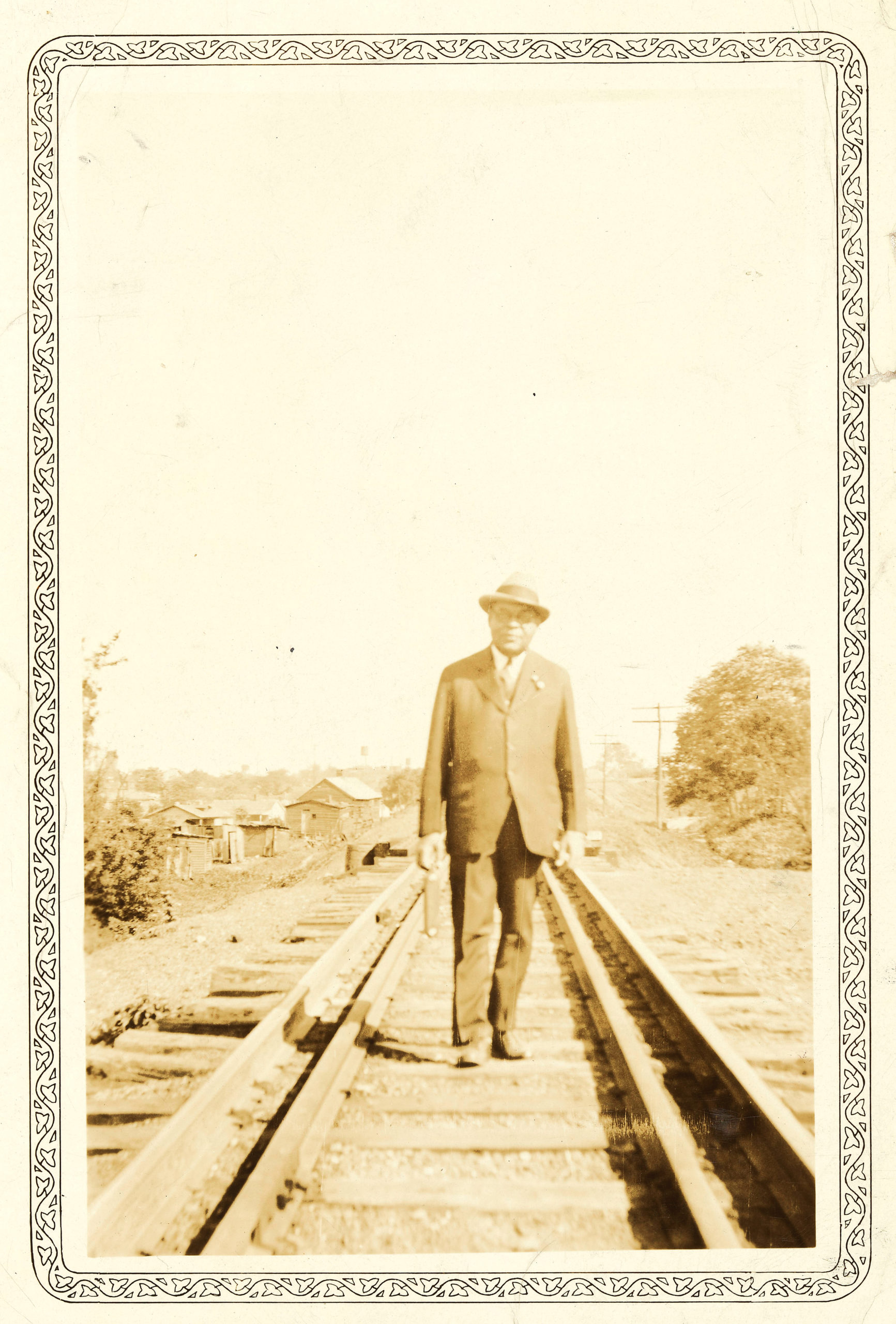

Pareja was a special project of Schomburg’s, explains Valdés, whose book, Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, was published in 2017. In 1926, Schomburg sold his private collection of books, archives and material culture to the Carnegie Corporation (the Carnegie then donated it to the 135th Street Branch Library in Harlem, where it became the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture) to fund a trip to Europe, beginning in Spain.

“His whole reason for being was to excavate, to recover, to recuperate all evidence of not only global Black excellence but also just Black presences in spaces where the narratives were saying that they were not,” says Valdés. Pullins notes that, after some rather romanticized treatment in the Nineteenth Century, scholarship of Pareja largely vanished by the Twentieth, but Schomburg was an exception, writing seriously about Pareja in the 1920s. It was important to both curators to acknowledge that the act of recovery they attempt with the present exhibition is not the first such effort.

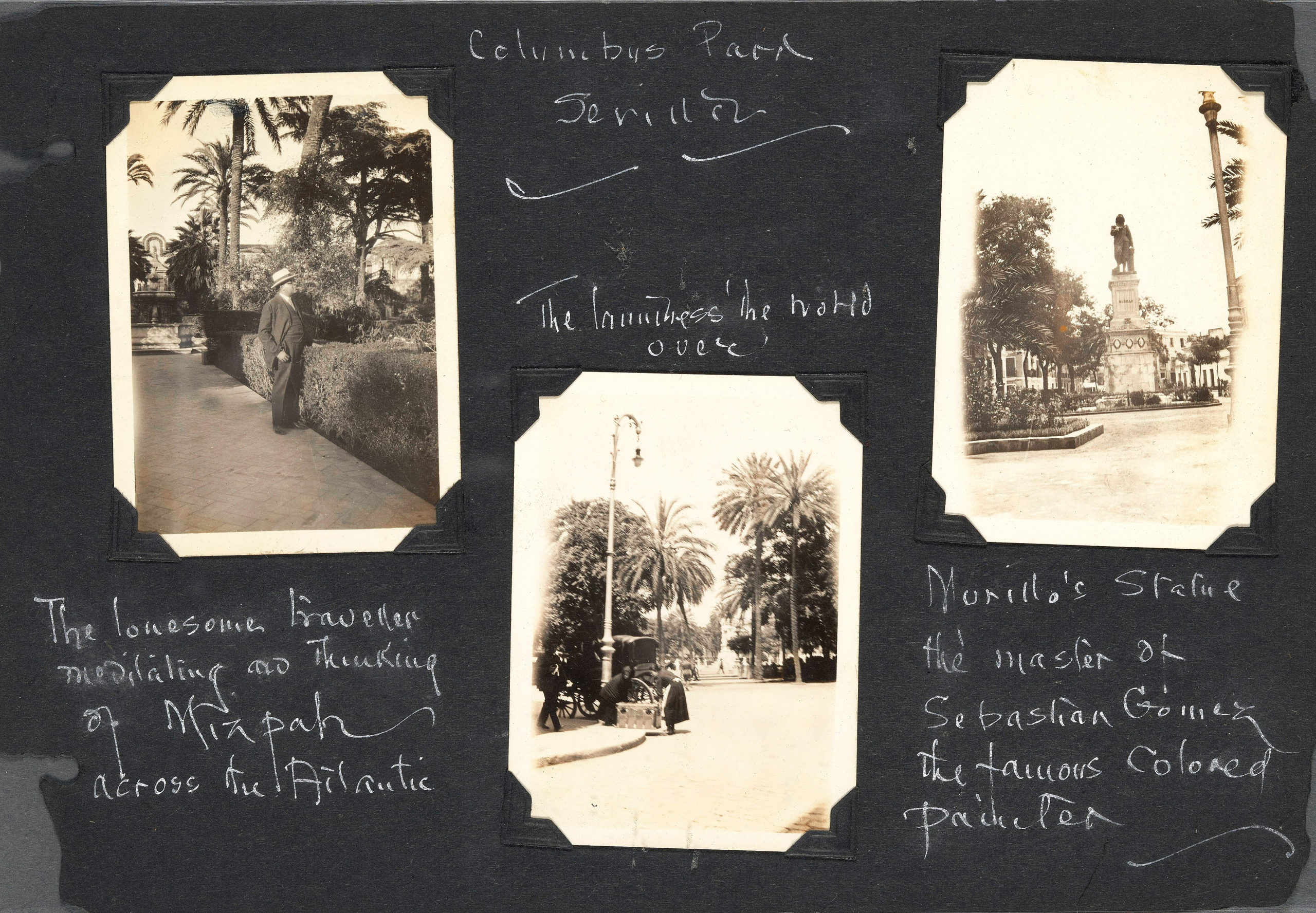

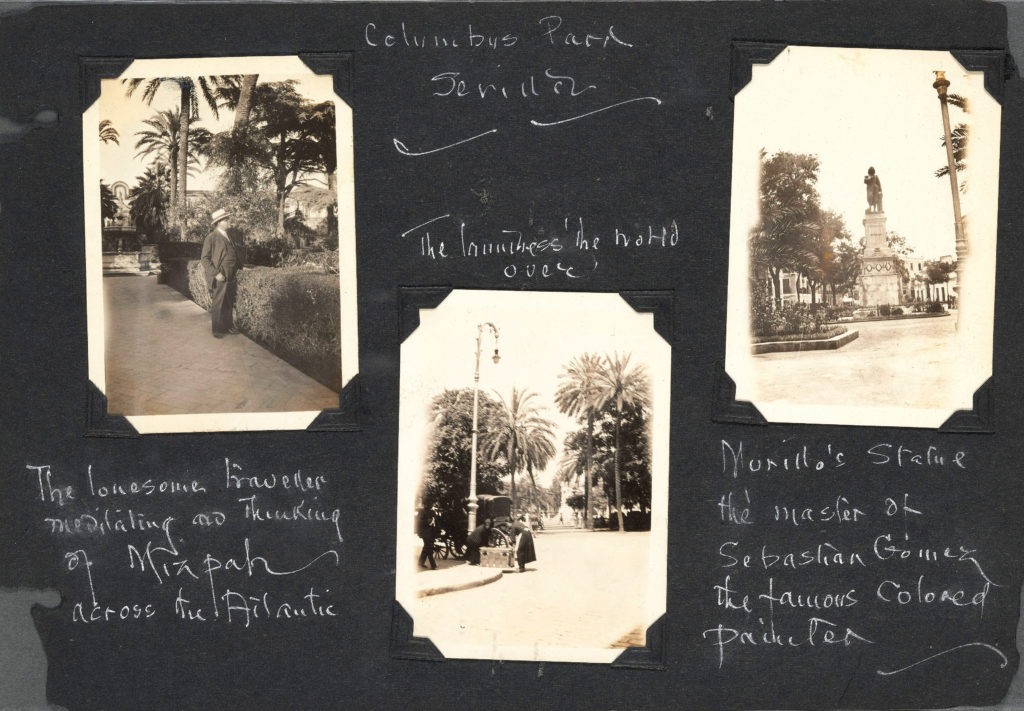

Mounted photographs from Arturo Schomburg’s travel to Spain, 1926, photographs mounted on paper, 6¾ by 9¾ inches. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Schomburg’s writings, photographs and collections fill the first gallery, providing context for what follows. The photos, on public view for the first time, are the kind of small, black and white snapshots that anyone in the 1920s might have taken on vacation, yet they are a valuable record of what Schomburg was interested in researching. Importantly, some show Schomburg himself, a Latino man of color and an intellectual, walking in the footsteps of others who came before him. Among Schomberg’s featured writings are his work not only on Juan de Pareja but also other important figures of African descent in Seville, including the Sixteenth Century poet Juan Latino — who became a professor at the University of Granada after, like Pareja, being born into enslavement. The volume by Latino that Schomburg collected and is now part of the Schomburg Center — “perhaps the first text written by a person of African descent on the European continent,” says Valdés — is here in this opening to the show.

Those whose introduction to art history began in the latter Twentieth Century might be forgiven for thinking of Pareja as a sort of rarity, a footnote to history; it may come as some surprise, then, to learn just how unremarkable his situation was in Seventeenth Century Andalusia. As contemporaneous works by painter Bartolomé Estéban Murillo and sculptor José Montes de Oca show — as well as additional paintings by Velázquez — people of African descent were a significant part of the cultural landscape; Valdés notes that some 10 to 15 percent of Seville’s population was enslaved, including artists and artisans who had reached a certain level of success. “This was quotidian,” she says. “Every single piece of art that we look at, every piece of silver, there were more often than not enslaved people who did that work.” (An essay by Luis Méndez Rodríguez in the accompanying exhibition catalog covers this important territory.) A variety of silver and other Spanish decorative objects from the Met’s collections are included in the exhibition, evidence, Valdés says, of the “intellect and skill” of these unrecorded makers.

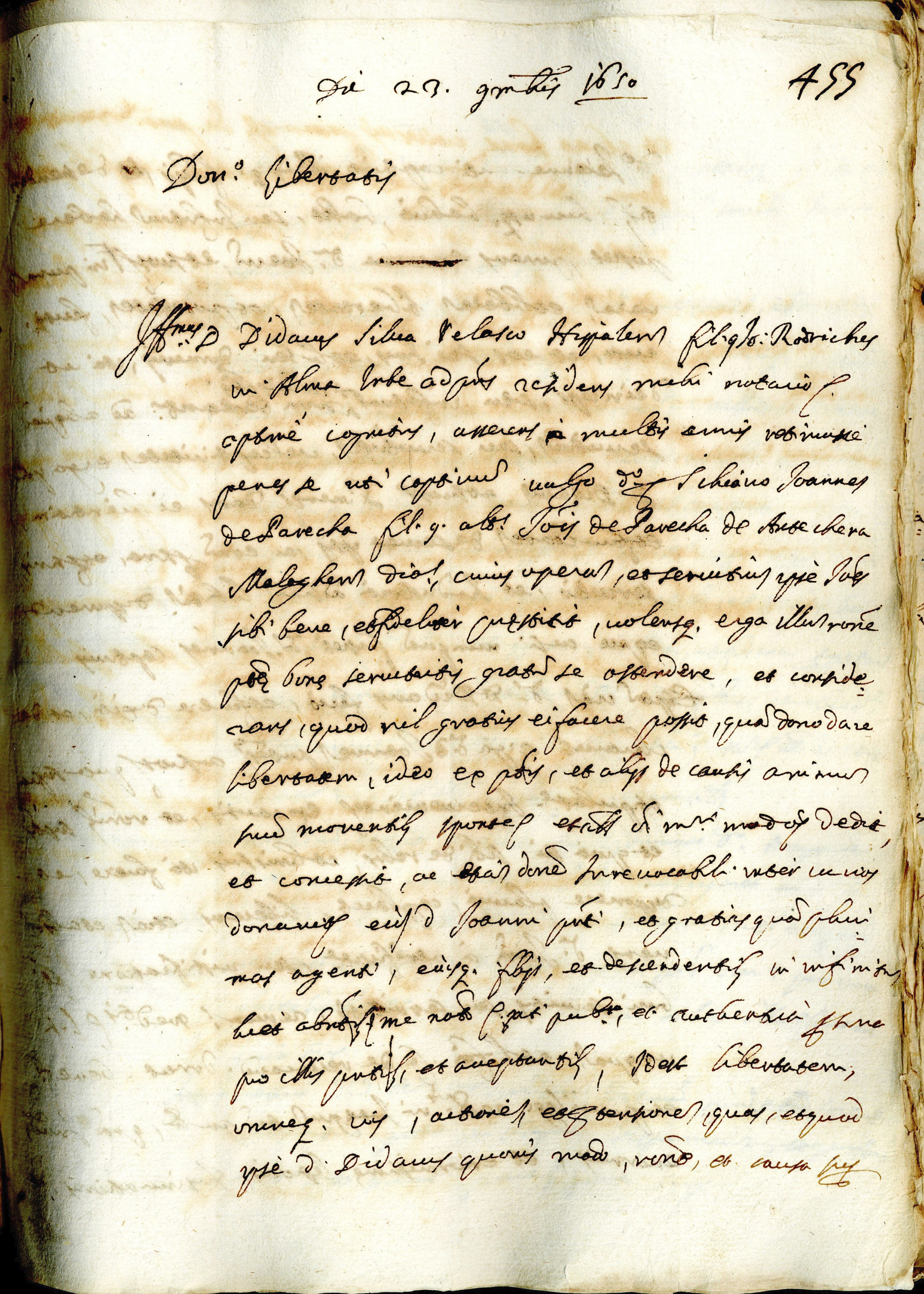

Key moments of this story actually take place not in Seville but in Rome, where Velázquez traveled in 1649 to secure commissions and to flesh out his own development as an artist. Three important things happened in Rome, possibly all in the same year: Velázquez painted a highly acclaimed portrait of Pareja, his enslaved assistant. In practically the same moment, he also painted a portrait of Pope Innocent X, an individual on the far opposite end of the spectrum of power and social standing. Finally, Velázquez signed a certificate of manumission for Pareja, which would release him from his condition of enslavement in four years’ time and enable him to strike out on his own as an artist. All three objects are on view. Pullins notes that the Juan de Pareja and Innocent X portraits are a “sort of classic art history pairing,” but the manumission document — translated and presented in a publicly accessible way here for the first time — broadens and grounds the investigation into this historic moment. Semi-apocryphal myths abound about the relationship between Velázquez and Pareja — that it was friendly and familial rather than that of enslaver/enslaved — but the manumission document is a stark statement of reality. “Nothing could be more factual than the transfer of property,” says Pullins.

“Calling of Saint Matthew” by Juan de Pareja, 1661, oil on canvas, 88-9/16 by 127-15/16 inches. Museo Nacional del Prado. Photo: ©Photographic Archive Museo Nacional del Prado.

In fact, Pareja’s personal history is not all that unusual, says Valdés. To the extent that, after 1654, he went on to have a flourishing career and make a significant name for himself is exceptional, to be sure, as it would be for any artist of the time, but neither his condition of enslavement nor his later manumission are exceptional. “What’s wonderful about Pareja’s story is that he gives you the nuance and depth of a biography, of an individual story that we essentially don’t have for any other individual maker,” says Pullins. In most cases, “there’ll be one moment, a glimpse: ‘So-and-so sold from so-and-so’s silver shop to another silver maker; he’s very good at gilding.’ You maybe have a first name, maybe not; he has a price. Otherwise, nothing.” No doubt due in large part to his association with Velázquez, Pareja’s unexceptional story has at least somewhat evaded that erasure of history.

It is true that Pareja is present in the written record in a way that other enslaved artisans of Seventeenth Century Spain are not; still, his story is most powerfully expressed through his paintings themselves. While some works convey his training with and influence from Velázquez — Pareja’s portrait of the architect José Ratés Dalmau echoes Velázquez’s numerous portraits of Spanish royalty and hidalgos, with their dark clothes, blank backgrounds, and haughty expressions — others show a conscious breaking away from what he learned in his enslaver’s studio. As a free man, he aligned himself with the so-called Madrid School, whose paintings had a lighter, chalkier palette than those of Southern Spain and who experimented with new forms of iconography.

It was possible to get many, though not all, of these works for the show. Beyond the complications of the pandemic and war in Eastern Europe — where two important works are held — many are in poor condition. The decision was made to focus on the strongest works, both in terms of their condition and their ambition, and to use the catalog to document the full scope of Pareja’s oeuvre, including works that either did not travel to New York or whose attribution to Pareja is somewhat up for debate. “I know that that will be an ongoing process,” says Pullins, “but it felt crucial that we get that foundational work out there.”

“Saint Benedict of Palermo” attributed to José Montes de Oca (Spanish, 1668-1754) circa 1734, polychrome and gilt wood and

glass, 49 by 34-5/8 by 16½ inches. Minneapolis Institute of Art. Photo courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art.

In the show, two 11-foot-wide paintings from the Prado, both with personal calling cards from the artist, are profound statements of artistic authority. In “Calling of Saint Matthew,” Pareja inserts his self-portrait as the face of one of the tax collectors on the far left (the figure holds a piece of paper with Pareja’s signature and the date). The face itself is so like the one in his portrait by Velázquez — the same tilt of the head, the same sidelong glance, the same magnificent mustache — that it is tempting to see it as almost the same painting, just with additional window dressing. But, in fact, the context matters a lot. Inserting himself into a New Testament scene, just as so many other Seventeenth Century painters did, is a “demonstration that he has attained a certain status, economically, financially,” says Valdés, that “he is in conversation with his contemporaries.” She adds that the opportunity to contrast Pareja’s self-portrait with his portrait by Velázquez is “too good to be true”; in fact, the two paintings provide the front and back covers of the exhibition catalog.

Pullins sees a similar authorial flourish in the second of the monumental Prado works, “The Baptism of Christ.” Pareja’s signature, which appears in the lower left as if carved into a rock crushing a serpent, is a “super-adamant claim to authority,” he says. The painting itself, made for a convent in Toledo, is markedly ambitious: a fully realized landscape, a cast of thousands on earth and in the heavens, fluttering draperies and angels’ wings. In these two works — both of which Schomburg saw in person and studied extensively — the curators see a kind of announcement of having arrived, a sense of, “I’m Juan de Pareja; I made this; look how accomplished I am,” in Pullin’s words. In doing so Pareja aligned himself with an elite group of Spanish, Catholic artists and intellectuals, people with a justifiable confidence that their names and their work would withstand the ravages of time.

In the end, Valdés says, neither the exhibition nor the catalog is “a revisionist text.” While there is an attempt to redress some of the omissions and mischaracterizations of earlier historians and art historians — the term “golden age” is avoided, for instance — the goal has not been to create a new history for Pareja but instead to pare the story down to what we know to be true. Pullins connects this to an overall idea of recovery that he roots in Schomburg’s work, observing that to treat him simply as an accomplished Seventeenth Century painter was “one of the most radical things we could do.” Valdés agrees, adding that with the exhibition and catalog “we recognize the skills of a person who lived in this moment, who actually garnered fame in his own right… Let us accord him that respect in the same way we do a number of people in that same era.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For information, 212-535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org.