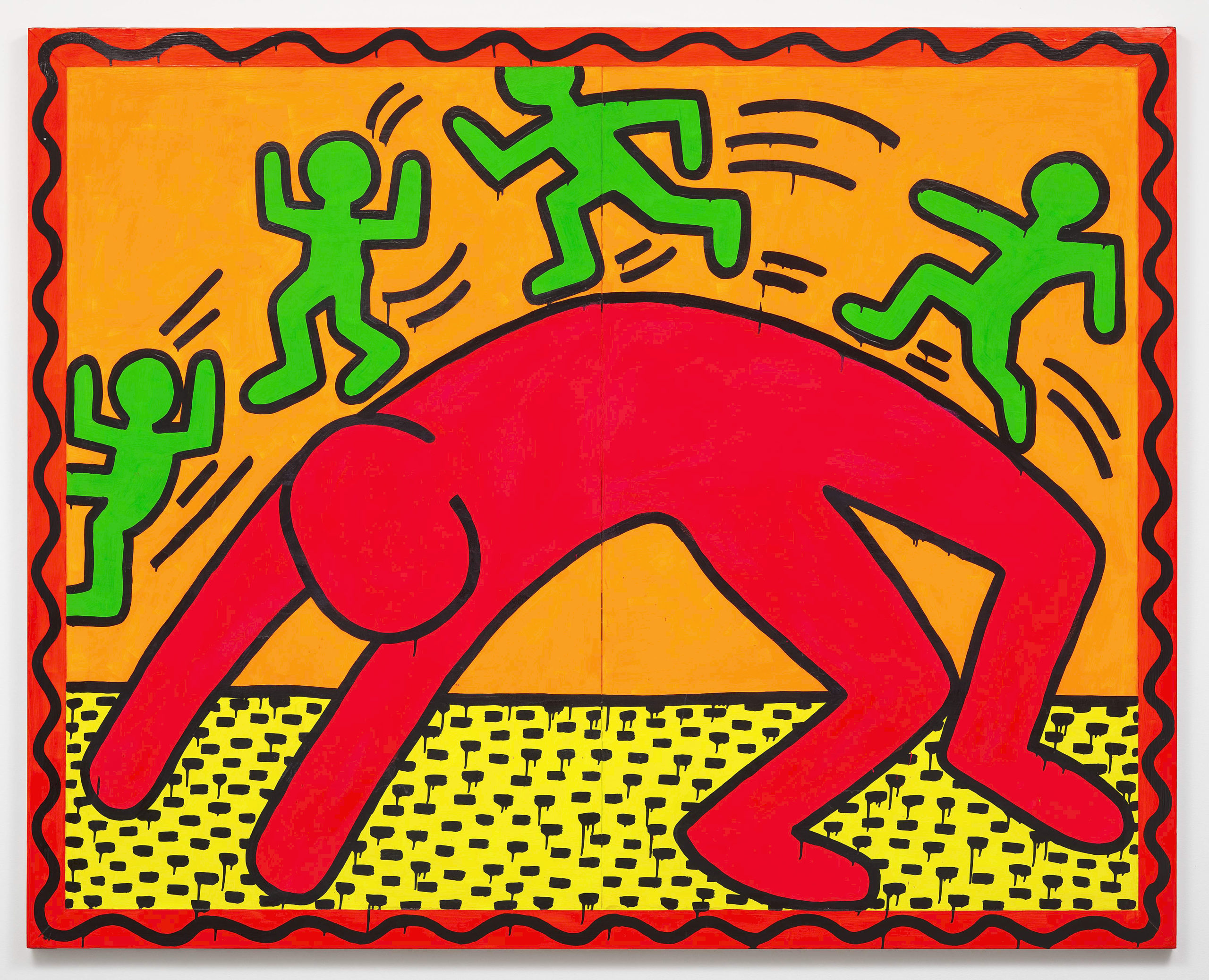

Untitled, 1982, baked enamel on metal, 43 by 43 inches. Photo: Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles. ©Keith Haring Foundation, courtesy of The Broad Art Foundation.

BY Kristin Nord

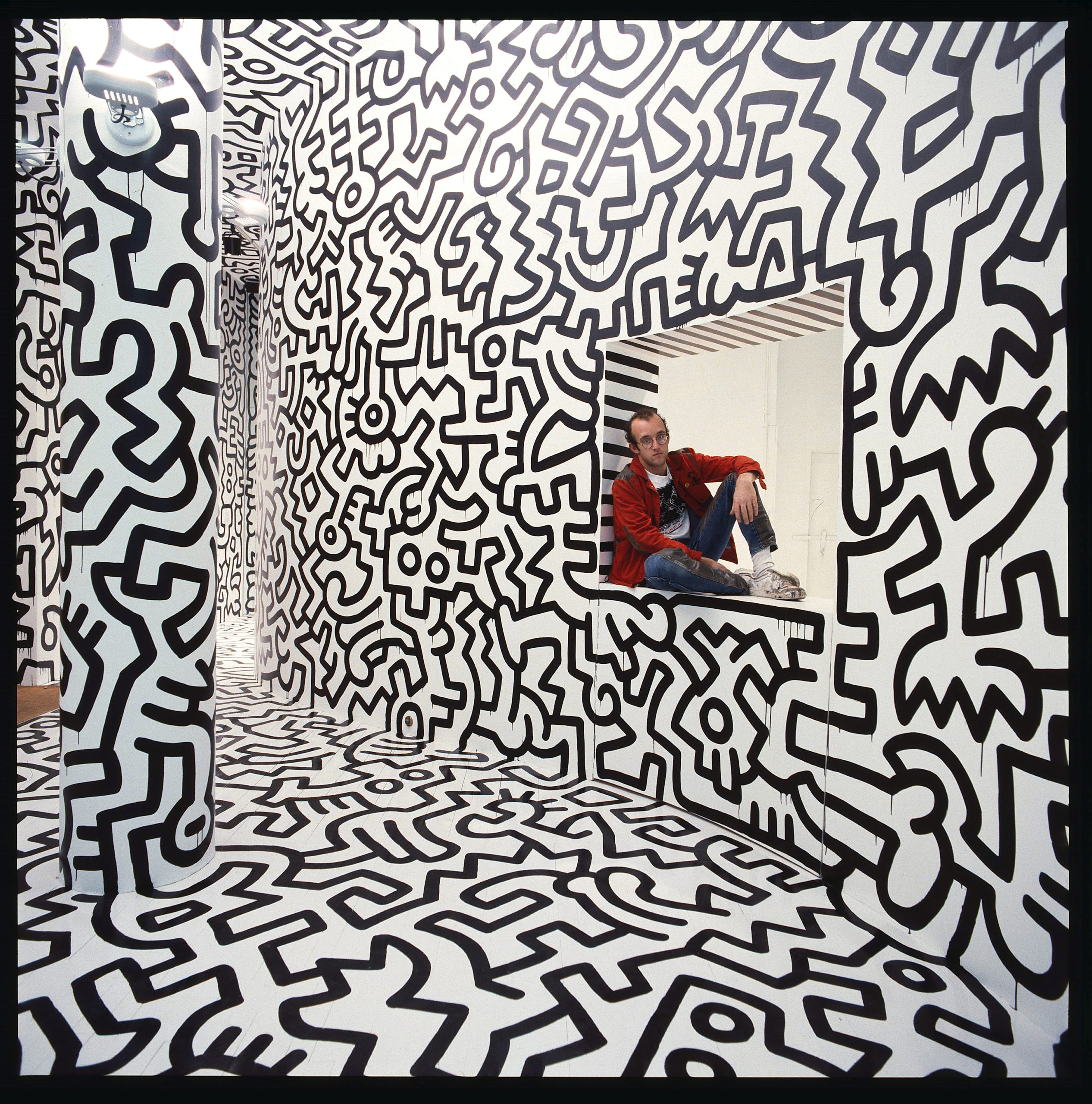

LOS ANGELES — “The Radiant Baby.” “The Barking Dogs.” “The Break Dancers.” And the power of his line. Keith Haring had just a decade in which to make his mark. And he succeeded. Some 33 years later people who do not know his name know his imagery.

Now in “Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody,” which is on view at The Broad museum through October 8, Angelinos have been invited to take a spirited deep dive into the artist’s life and practice. The exhibition, curated by Sarah Loyer, is the first stop of a three-leg tour that will include the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis as well.

“Though Haring was a young artist still developing his artistic style, the early assertion that ‘art is for everybody’ remained a belief and ambition that drove his practice for the rest of his life, along with the conviction that artists have the obligation to make work that reaches as many people as possible,” Loyer asserts, in the exhibition’s catalog.

“Defying the odds, Haring’s work accomplished this, reaching a wide and varied audience during his lifetime and into the present, through traditional mediums like painting and sculpture as well as unconventional methods like making work in public spaces and without advance permissions giving away promotional buttons and selling merchandise,” she adds.

Untitled, 1983, enamel and Day-Glo paint on incised wood. ©Keith Haring Foundation, Courtesy of Edward Tyler Nahem.

His ascent had begun humbly enough, with his dad offering him a lift from the family home in Kutztown, Penn., to Manhattan, where he had been accepted as a scholarship student at the School of Visual Arts. Haring brought with him a “certainty about making himself an artist, uncertainty about everything else — and a lively shot of talent,” the writer Ingrid Sichey, notes, in a poignant profile of the artist seven years after his death.

As a boy, he had learned cartooning from his father. By his teenage years, he had been inspired by the public art of Pierre Alechinsky, Jean Dubuffet and Christo. When he encountered the poet Brion Gysin’s “cut up technique,” he grasped intuitively the ways in which he might create a visual equivalent. His pictographs of the radiant baby, barking dogs and writhing break dancers would become his answer, functioning as fundamental elements in the visual language he was building. They could take on “new, ever-evolving meanings,” and would pop up in recurring combinations. And pop up they did, first in the subway stations of New York City, and later all manner of surfaces and media. Haring chose the empty spots on walls of subway stations first, and his feverish pace often accompanied by his own music soon attracted a public following.

“Drawing with chalk on smooth black paper was a completely new experience for me,” he reported later, in an interview that appeared in Arts Magazine. “It was one continuous line, no interruptions needed to be made, as with a brush or whatever else was already dropped in the paint. I had to work as fast as I could. And nothing could be corrected. So, mistakes could not even be allowed, as they were. I had to be careful not to get caught.”

“Pop Shop, New York” by Tseng Kwong Chi, 1986. Photograph: ©Muna Tseng Dance Projects Inc. Paintings: ©The Keith Haring Foundation.

“The subway drawings were, as much as they were drawings, performances. For me, it was a whole sort of philosophical and sociological experiment.

“When I drew, I drew in the daytime which meant there were always people watching. There were always confrontations, whether it was with people that were interested in looking at it, or people that wanted to tell you you should not be drawing there.…” And Haring interacted “with every range of person you could imagine, from little kids to old ladies to art historians.”

It was also a time when he embraced his sexuality as a gay man and reveled in the city’s club culture. He swiftly became a celebrity in his own right, who created more than 50 public art works between 1982 and 1989, many of which carried social messages, and many of which he completed with the aid of children.

Haring’s advocacy — for safe sex, for AIDS awareness, and for a world in which tolerance and diversity is accepted and apartheid in South Africa has been dismantled — was impassioned and heartfelt. He took on political corruption and the excesses of capitalism in such works as Untitled (1984), installed on The Broad’s third floor skylit gallery. In his mural “Crack is Whack,” still visible on the FDR Drive in Manhattan, he addressed the crack cocaine epidemic that was decimating poor neighborhoods in New York boroughs. His posters promoting safe sex and warning of the perils of the AIDS crisis remain haunting images from that tragic era. And Haring’s articulations could also pop up in smaller vessels, as in a vase-as-funeral-run in which Haring’s break dancers are marked as casualties.

Three-piece leather suit by Keith Haring with LA II (Angel Ortiz), 1983, leather and paint. The Keith Haring Foundation. ©Keith Haring Foundation.

Throughout the 1980s, Loyer notes, “whether in the subway drawings, the street murals, or later the goods he sold in pop shops in New York and Tokyo, his decisions on scale, site and the work’s physical vehicles are informed by a populist desire for accessibility. His decision to produce his ink drawings on tarpaulins in the early 1980s came out of a related impulse, a resistance to the elitism he thought implicit in oil on canvas,” she added.

Haring’s figures at times shimmer with joy; and no doubt continue to shake conservative rafters with his homages to penises and orgiastic gay encounters. There were, however, increasingly, works that declared that all was not right with the world. There were his serpents and monsters, nuclear radiation towers and falling angels, his cannibals, omnivorous worms, bloody daggers and skeletons. Much as his friends Andy Warhol and Jennifer Bartlett had tapped into the undercurrent of death and violence of the 1980s, he fashioned works with tabloid-style headlines which he posted around New York City.

David Galloway, who contributed an essay to the book, Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell, noted that Haring’s early career was “neither so innocent nor so giddily affirmative as it is sometimes made out to be. His media-savvy generation, exposed at an early age to sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll” had been quickly disabused of childhood’s illusions. At the tender age of 19 he had confided in his journal: ‘Through all the shit shines the small ray of hope that lives in the common sense of the few. The music, dance, theater and the visual arts: the forms of expression, the arts of hope. This is where I fit in.’”

Like the Beat poets Haring admired, Galloway continued, “he was intensely aware of the dangers of nuclear war and the precedent his country had set in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The notorious meltdown at Three Mile Island occurred 50 miles from the Haring home in Kutztown. Spaceships projecting rays onto earthlings often hover over his works, and his famous ‘radiant’ baby may suggest radiative contamination, as well as spiritual glow, the key to his work found in the mingling, the marriage of innocence and experience, good and evil, heaven and hell.”

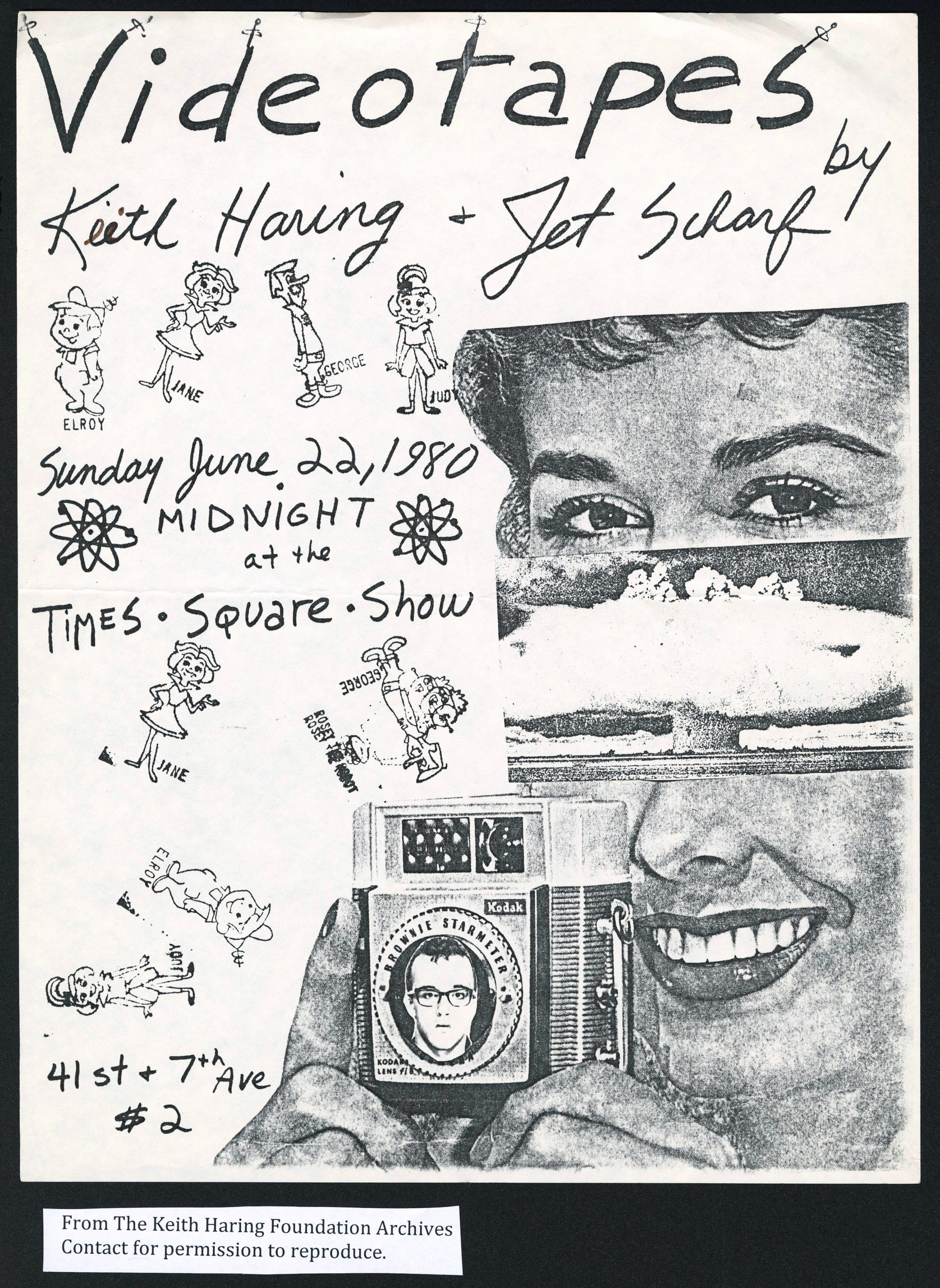

Videotapes by Keith Haring and Jet Scharf, n.d., flyer. The Keith Haring Foundation. ©Keith Haring Foundation.

While Haring is known mostly for his paintings, he also made sculptures, videos, prints, drawings, works on paper and graphic materials. The exhibition taps into the breadth of his output, from the poster Haring distributed at a 1982 nuclear rally, and a bus shelter advertisement for an AIDS hotline, to his significant public works and videos of his collaborations with dancers and musicians.

Eli and Edythe Broad were early Haring aficionados, and eight works from their permanent collection, including “Red Room,” his homage to Henri Matisse, are among the 120 works that figure prominently. A black-lit gallery simulates the 1980s club scene with a Haring playlist unfolding on a spool.

The art critic David French observed, “Like many of his 1980s contemporaries, Haring consumed earlier visual forms, but he was less an appropriator than a terrific synthesist. It was not that he looked at Paradise Garage instead of looking at Legér, Matisse, Arabic decoration, Pierre Alechchinsky, Frank Stella, Stuart Davis or Walt Disney (to name just a few of the connections one can make when looking through catalogs of his work), but that he looked at them all, then rephrased them through the syntax of that flowing and recombinant line.”

Untitled, 1982, enamel and Dayglo on metal, 72 by 90 by 1½ inches. Private collection.©Keith Haring Foundation.

Public programming events organized by Haring friends and contemporaries will offer the public a chance to immerse oneself 1980s club life, a la the infamous Neo-Dada cabaret Club 57 with performance artist and longtime manager Ann Magnuson once again at the helm. In August there will be a blow-out 50th celebration of hip hop, Angeleno-style. Anyone who has seen recent LA dance competitions knows it will be an evening of break dancing, social commentary and spectacle, just as Haring might have wanted it.

Haring had strong positions on matters of religion, his own Queer identity and race. And he remained a social activist in the final years of his short life, making art with undiminished intensity right up until the end. When he died from complications from AIDs in 1990, some 1,000 attended his funeral at the Cathedral of St John the Divine. His had been a meteoric ride.

The Broad is at 221 South Grand Avenue. For information, www.thebroad.org, info@thebroad.org or 213-232-6200.