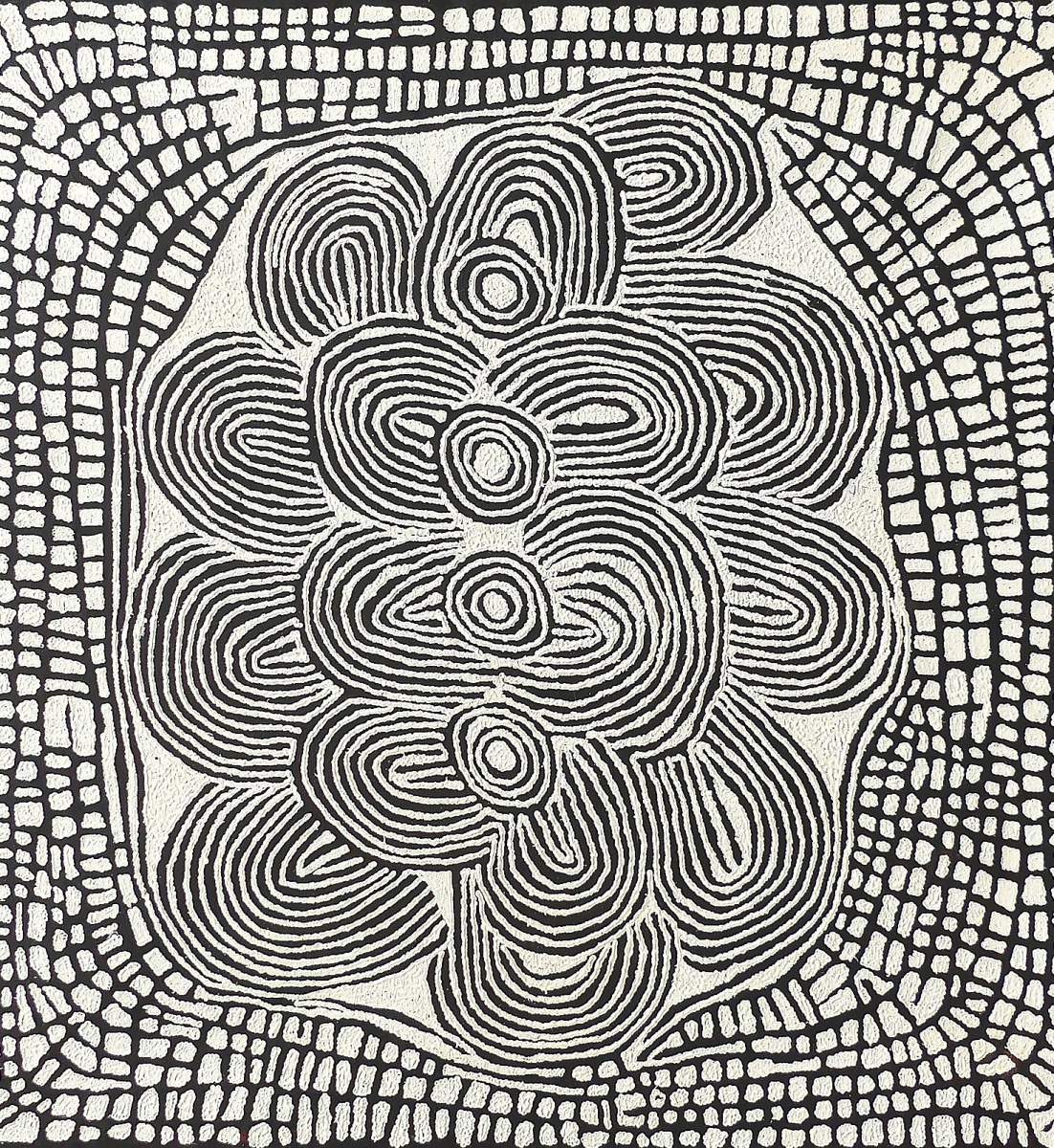

“Pikilyi” by Michael Jagamara Nelson, AM (Warlpiri, 1949-2020), 1990, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 71-5/8 by 71-5/8 inches. Kluge-Ruhe Collection of Aboriginal Art of UVA, Gift of John W. Kluge, 1997.

By Z.G. Burnett

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA. – What is an artist’s connection to the land they call home, and how does that affect how they perceive themselves, and the art that they create? These are just a few of the questions addressed in “Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu, Past & Present Together | 50 Years of Papunya Tula Artists,” currently on view at The Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia. The exhibition celebrates the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Papunya Tula school, which began in an Australian resettlement community that was organized to house displaced Aboriginal peoples. These community members came from disparate areas of the country, finding common ground with the inherited stories they preserved by sharing them. The Aboriginal peoples of Australia do not have a written language and pass their histories through story-telling and visual art, the combination of which is showcased in this exhibition both in person and online.

The story of Papunya’s beginnings in the Northern Territory of Australia is regrettably similar to other resettlement communities in most colonized countries and is also the barren canvas upon which the original artists and others that came after painted their own stories. As the expansion of foreign farmers and their industrialization of the land became a drain on water and other natural resources in the 1930s, also due to other to environmental changes, traditionally nomadic Aboriginal groups were pushed out of their ancestral homelands on which they had hunted and foraged for thousands of years. These encounters often ended with violence between the newcomers and the original inhabitants of the land, ultimately displacing the latter group and forcing them to rely on governmental ration depots.

As refugee numbers grew, the Australian government built water bores and housing in already-established Aboriginal territories in the 1950s, not considering the linguistic and tribal differences between these peoples. At this time, the Australian government was also still occupied with assimilating the Indigenous inhabitants into adopting the culture, behavior and belief systems of white Australians. Depending on where these people had lived, some had contact with white colonists before, while others where only meeting settlers for the first time. Papuyna mainly consists of the Pintupi and Luritja people, who come from the Western and Northern territories, respectively. There are more than 250 distinct languages spoken in Australia and many cultural differences between regions. In addition to these two groups, many were being housed together at Papunya Tula in basic, soon crowded living situations.

From its beginnings in 1959, Papunya’s population grew from about 400 to 1,000 in 1971, with tensions between tribal groups, the introduction of alcohol, poverty and disease afflicting the settlement. These conditions were a result further expansion into traditional territories as well as Indigenous people being unable to return to their homelands once entering the compound to share in its resources. At this time, a small group of men began using materials from the Papunya school to record their stories and experiences. Aboriginal art up to 50,000 years old has been found on the rock formations of Australia, made with natural materials in a number of regional styles. Far away from these places, the men began to create new art with cardboard, acrylic paints, anything they could find to record the culture they believed would be lost if it was not preserved.

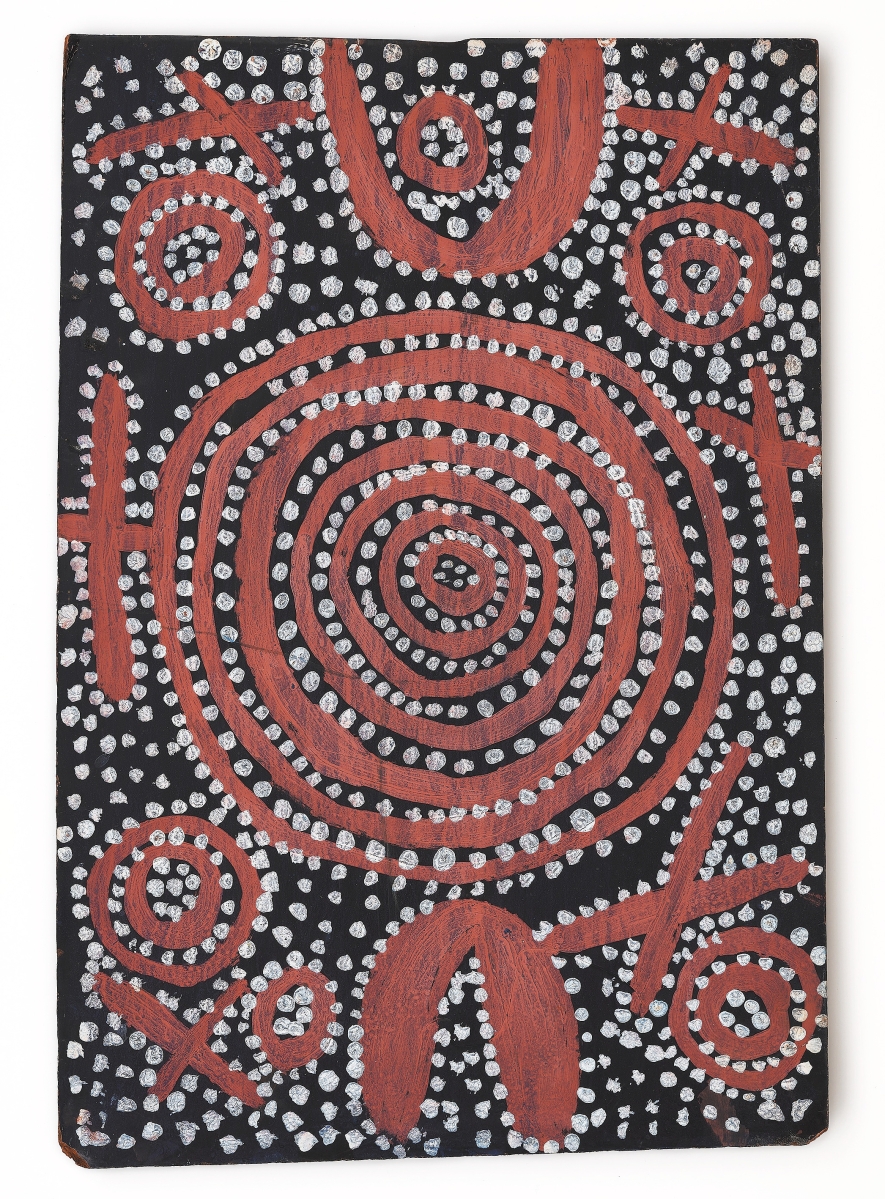

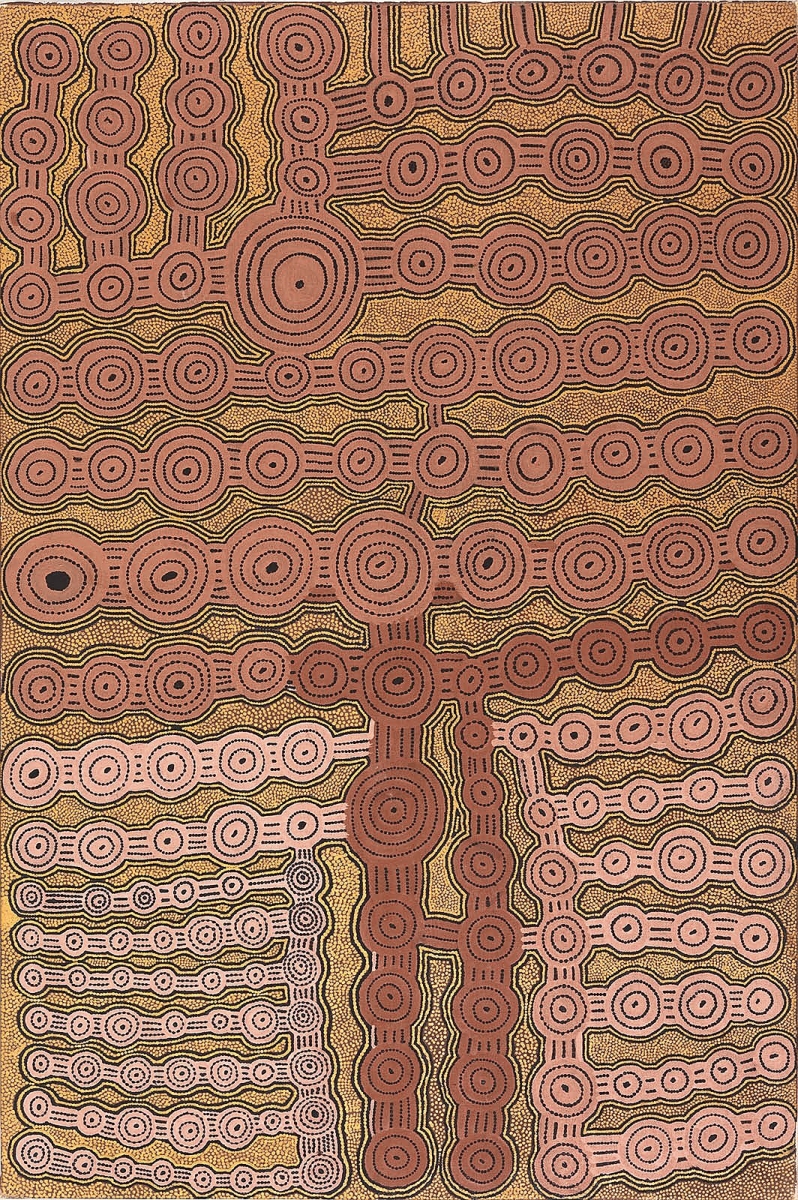

“Tingarri Cycle At Minyurlpa Near Jupiter Well” by Dini Campbell Tjampitjinpa (Pintupi, 1942-2000), 1988, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 72 by 48-1/8 inches. Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of UVA, Gift of John W. Kluge, 1997.

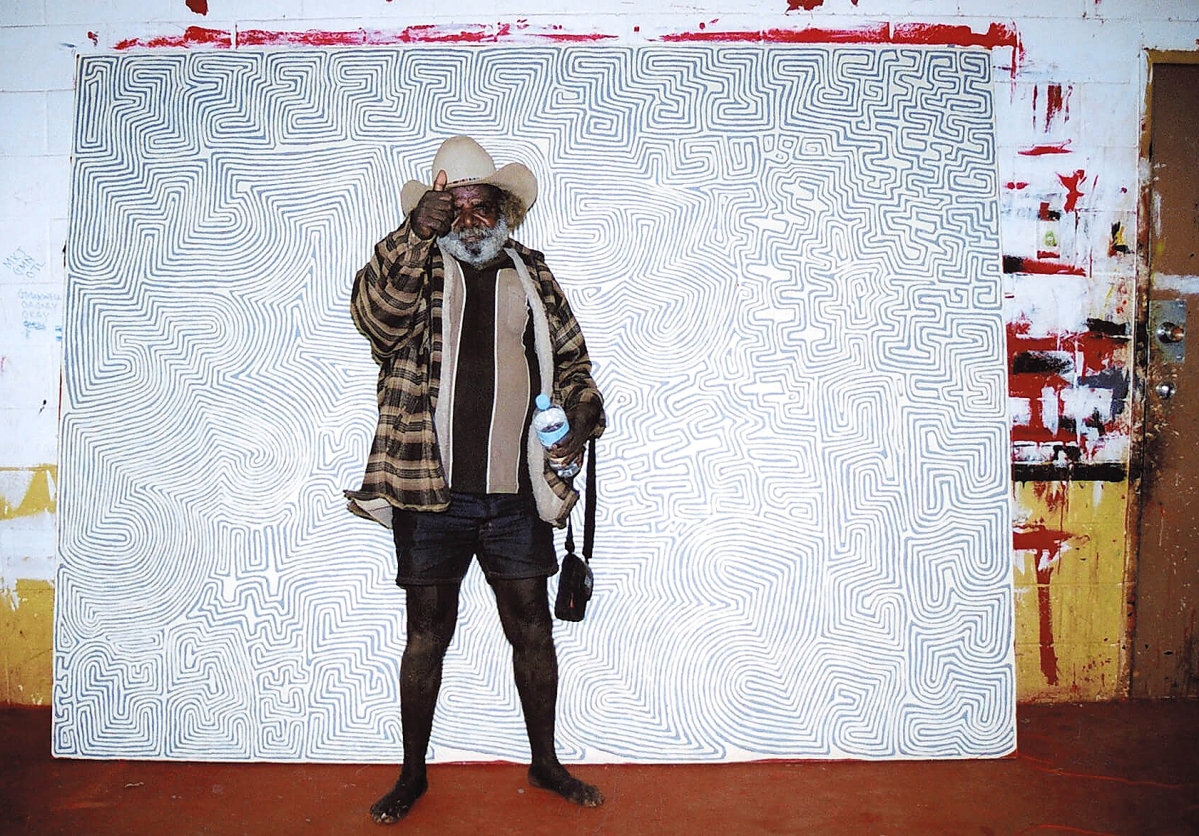

In this same year, the community’s new primary school teacher Geoffrey Bardon (Australian, 1940-2003) noticed the paintings, which were made with ancient designs usually restricted to specific Aboriginal communities and rarely shared with others. Bardon organized an art center for this activity, providing materials and encouragement to those who wanted to share their ancestral stories, many of which are interrelated to the lands from which they had been removed. In July 1972, the artists decorated the school exterior with a mural and founded Papunya Tula Artists Pty Ltd. in 1972, becoming the first Aboriginal-owned artistic company in Australia. As the art and artists gained worldwide recognition, the center became a unique and important source of economic opportunity for the community. Within the next decades, some artists represented by Papunya Tula were able to relocate back to their homelands at Walungurru and Kiwirrkurra and continue creating art with the company’s representation.

It was at this time that collectors Edward L. Ruhe (American, 1923-1989) and John W. Kluge (German-American, 1914-2010) began to acquire Aboriginal art, including that of the Papunya Tula school. Ruhe began collecting in 1965 while living and working in Australia as a Fulbright visiting professor and was the first to exhibit a privately owned collection of Aboriginal art in the United States which toured between 1966 and 1977. Kluge was first captivated by the Papunya Tula exhibition “Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia” at the Asia Society in New York City in 1988, and afterward began buying and commissioning Aboriginal art with the help of curatorial advisors. Following Kluge’s passing, Ruhe acquired his collection and donated it to the University of Virginia in 1997. The Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection opened in 1999 and is the most significant collection of this kind outside of Australia. With this shared history, the museum was a natural choice for the 50th anniversary exhibition of Papunya Tula art.

In 2007, the Papunya Tula artists formed their own independent center, Papunya Tula Arts, who guarantee immediate payment for completed works. While Papunya Tula is an international entity and the financial cornerstone of the Aboriginal community involved with the school, providing housing, food and medical care that has historically been absent or underfunded, the Western Desert artists remain unfazed by their success and fame. Their primary objective and drive to preserve their ancestral stories, which drives them to create art and thereby perpetuate the mission of Papunya Tula.

Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, Walungurru (Kintore), 1997. Photo by Paul Sweeney.

The vast impact of Papunya Tula’s success on the widespread Aboriginal community cannot be overstated, as many different cultural groups participate and benefit from the company. Each of these have their own distinct style depending on a host of factors, including region and family groups. This gave Henry F. Skerritt, curator of the Indigenous Arts of Australia at the Kluge-Ruhe and of the exhibition, a wealth of objects to choose from, yet with this came difficult decisions to be made. “The biggest challenge [was] representing all the diversity!” Skerrit said, “Over 50 years, Papunya Tula has had so many extraordinary artists. Getting them all into two exhibitions was a huge challenge. And even then, there were significant artists we had to cut because we didn’t have room!”

“Past & Present Together” also includes an interactive online gallery of the exhibition, opening with both an acknowledgement of Indigenous custodians of the land and a disclaimer for Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander site visitors. The Kluge-Ruhe is conscientious about recognizing the Monacan Nation as original custodians of the land upon which the collection is built and is committed to promoting awareness and inclusion of Indigenous peoples in the arts, both in the United States and worldwide. The site also alerts Indigenous Australian visitors to the presence of first names, images and voices of deceased people within the exhibition; not naming the dead is an avoidance custom in many of these communities, both as a mark of respect to the deceased person and to their grieving families. This mourning period can last from one year to many years.

The interactive exhibition is a visual representation of the extensive nature of the subject, which in its essence expands throughout time and space while still celebrating the Papunya Tula artists’ spiritual and physical connection with the land. By clicking and dragging the page, visitors can explore the works in all different directions. These individual thumbnails open into full catalog listings of all included paintings; the only detail that does not translate directly from the screen is the size of these canvases, many of which are quite large and were created by multiple artists. The works are not grouped by subject, artist or date, emphasizing the concept of togetherness among diversity within this movement.

“The story of Papunya Tula Artists is a story about innovative and talented individuals, but it is also a story about community. We wanted to lay out the website to honor those connections; to show how the works relate to each other as well as to highlight their individual virtuosity,” Skerritt explained. “Many people might not necessarily grasp the familial or narrative connections between the works as they are laid out across the screen, but hopefully they will see some of the visual affinities. It was quite deliberately laid out in that respect.”

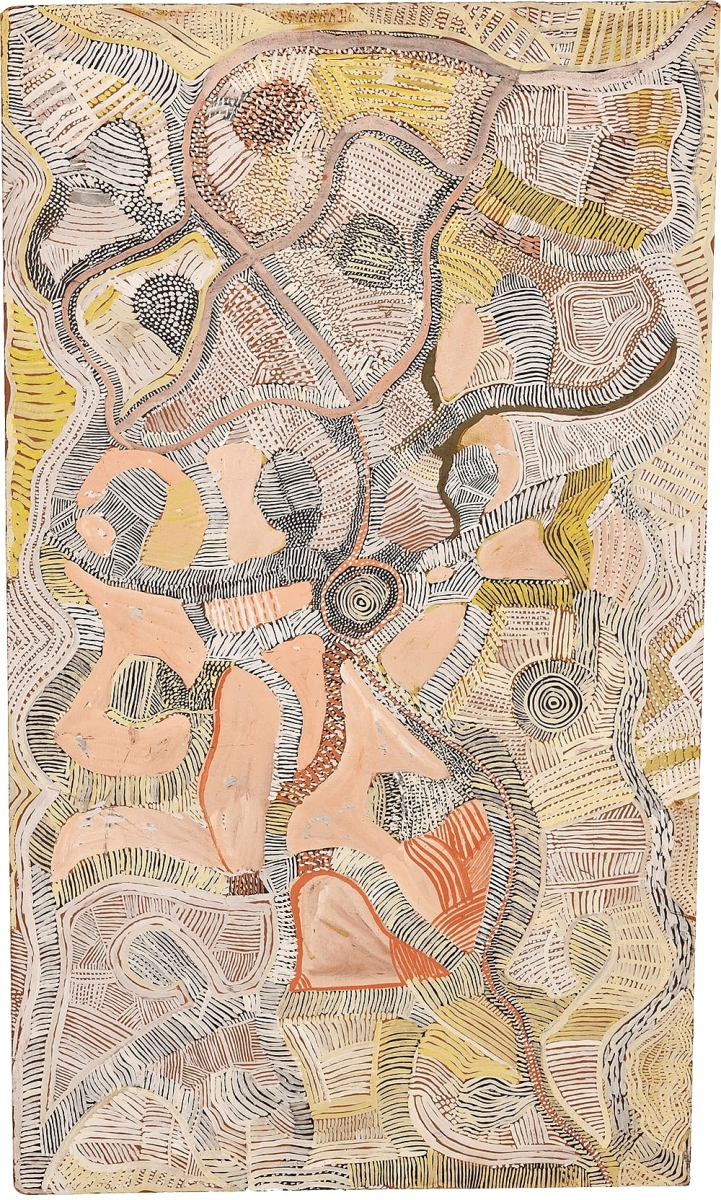

“Kungka Kutjarra Tjukurrpa (Two Women Dreaming)” by Tatali Nangala (Pintupi, 1928-1999), synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of UVA, Gift of John W. Kluge, 1997.

One of the predominant themes in Aboriginal art is Tjukurrpa, or “Dreamings.” Unlike the Western conception of dreams and dreaming, “Dreamings” are a complex system of beliefs that impact all aspects of life and explain their connection to the land, including their ancestral connections. Much of the art includes creation stories that have been passed down to the artists, as well as songs and ceremonies related to these happenings that continue to be practiced today. An all-encompassing term best defined on the exhibition’s virtual gallery, Tjukurrpa “exists in its own sense of time: it is neither an eternal present nor an eternal past, but rather a constant state of past and present together.”

An important and major subject of the exhibition is the contribution of women to the Papunya Tula movement, especially as their efforts were sidelined or not encouraged by non-Indigenous people in the beginning of the company. The wives and daughters of the first generation of male Papunya Tula artists would assist in the dotting of backgrounds on larger works, with only a few women creating their own artistic space in the early 1980s due to lack of funding to support new artists. By the 1990s, women at Ikuntji nearby Walungurru became so successful in creating art from and on their community women’s center that Marina Strocchi (Australian, b 1961) was hired to assist in a collaborative workshop, during which up to eight women at a time would work together to express their individual Dreamings. As these works gained recognition from within the community and the international art market, the women’s perspectives, spiritual life and deep knowledge of the land and its stories became an essential and revitalizing addition to movement.

The third generation of Papunya Tula artists are currently creating new work, along with the assistance of their younger family members. These artists are generally in their 60s or 70s. Although one does not need to be an elder to be an artist for the company, the senior members of the community have learned their family’s stories and ways of making art throughout their entire lives. Elders are held with great esteem and respect within the many cultural groups that compose Papunya Tula, and their guidance is invaluable for navigating contemporary life even in the most remote of places. Many younger artists are currently emerging from these generational groups, most in their 40s and 50s but some in their 30s. These artists will often paint in their parents’ style until they gain respect in the company and, therefore, the community, then they will begin to innovate and develop their own style. “This is an example of continuity,” Skerritt explained. “[These groups] are very culturally strong and alive.”

Many of these paintings contain sacred or ceremonial information that is forbidden to share, especially to uninitiated Aboriginal and non-Indigenous people. Dotting, or Walkatjurninpa, was one way to conceal these details and also an ancient and universal form of marking, whether it be on stone, skin or a canvas. Papunya artists use dots and line work to create deliberate, time-consuming patterns, sometimes with many artists working on a single canvas. The paintings can tell one story, many stories or the same story all at once by different hands. The artists place the main importance on the act of the storytelling itself, while also satisfying a large range of needs and wants with their cultural production. The Kluge-Ruhe Collection looks forward to continuing its collaboration with the Papunya Tula school on future projects. “Papunya Tula Artists are so integral to the history of Aboriginal Australian Art generally and to the Kluge-Ruhe more specifically,” Skerritt said. “And their story is ongoing, so I hope that in ten or 20 or 50 years we can revisit the story because, if the last 50 years are any indication, it is going to go in directions that none of us could have predicted!”

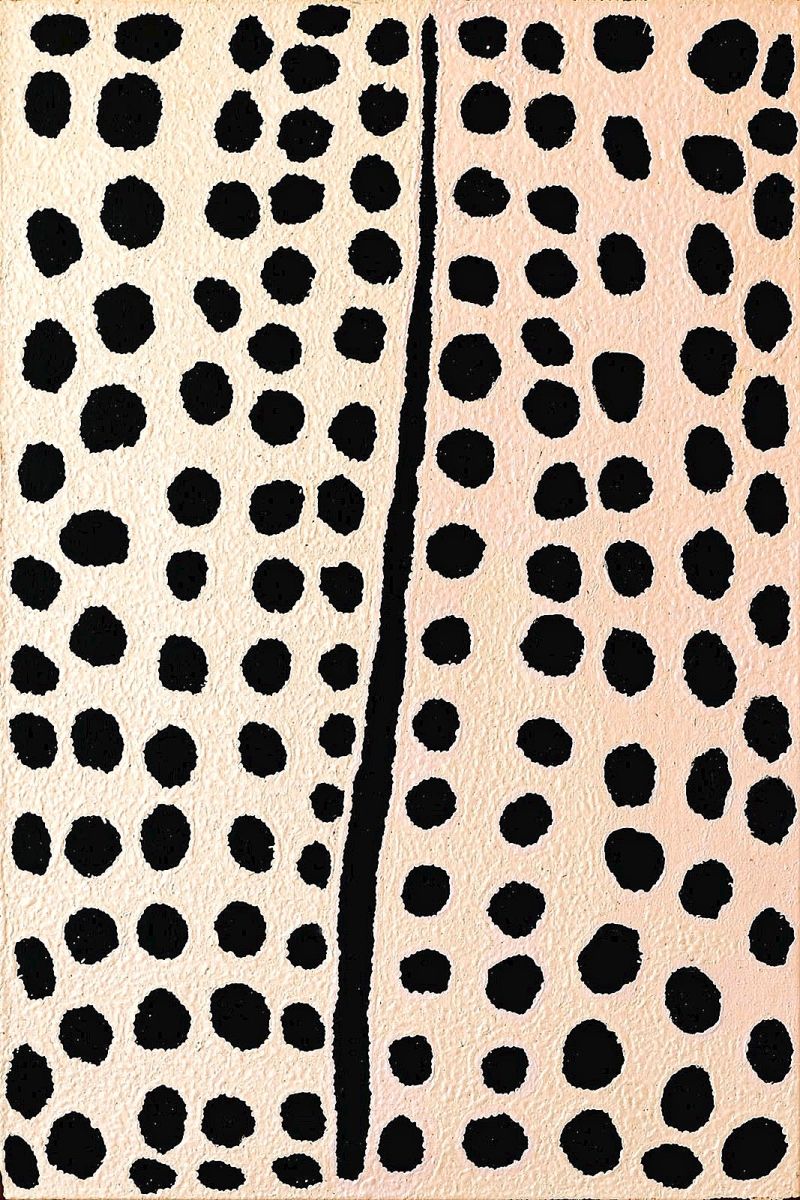

“Nynmi” by Josephine Nangala, 2020, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 24 by 21-5/8. Commissioned by Richard Klingler and Jane Slatter for “Past & Present Together.”

The exhibition is presented in two parts; Part I explored the beginning of the movement with works from 1971 to 1994; it is no longer on view, but the works are visible in the online exhibition. Part 2, on display until February 26, examines contemporary and emerging artists in the Papunya Tula school with paintings from 1996 to 2021. The exhibition will then be on display at the Australian Embassy in Washington DC.

The Kluge-Ruhe collection will present “Madayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala” in collaboration with Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala, Australia, on view at The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, until December 4.

The Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection is at 400 Worrell Drive. For information, 434-243-8500 or www.kulge-ruhe.org.

[Editor’s note: The catalog for this exhibition, Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu (Past And Present Together), edited by Fred Myers and Henry Skerritt, can be purchased from the University of Virginia Press.]