Reconstruction of cubiculum, as installed at the Smith College Museum of Art by Tim Lydell, 2017. Visitors to the exhibition can sit and linger in this digitally reconstructed room while listening to trickling water and voices speaking Latin. —S. Petegorsky photo

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NORTHAMPTON, MASS. – Unimaginable luxury and unspeakable tragedy. The beauty and terror of the natural world. A pinnacle of human creativity and the destructive powers of the earth and of time. All collide evocatively in “Leisure and Luxury in the Age of Nero: The Villas of Oplontis Near Pompeii” at the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA), the only East Coast venue for this internationally traveling exhibition, through August 13. The exhibition, along with its accompanying catalog, are the major public offering of a decades-long project to unearth, study and breathe life back into the lost Roman city of Oplontis, entombed by volcanic ash nearly 2,000 years ago.

When something tragic happens, when lives are lost and witnesses are few, it is often only through the wreckage left behind that we can piece together what happened. It is tempting, then, to see the archaeologists who work on the homes and cities buried in ash by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE as something like crime scene investigators or forensic scientists, assembling often tiny, seemingly insignificant pieces of evidence to reconstruct a narrative of a catastrophe that resulted in death and loss on a massive scale. But archaeologists of the villa sites on Italy’s Bay of Naples – the area hit hardest by the eruption – are not primarily interested in that disastrous event that blacked out the sky with ash and poisonous gas for two days. They are, as a general rule, more interested in what came before it.

The thick piles of ash that rained down on the bay buried and effectively froze in time a golden era of life in antiquity, a life filled with art, gold, wine and lush villas and gardens – all supported and nourished by the work of slaves. Many individuals are already familiar with Pompeii – the first of the Bay of Naples sites to be rediscovered, in phases, in the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries. But for them, as much as for any other visitor to “Leisure and Luxury,” the “villas” of Oplontis are likely to be a revelation.

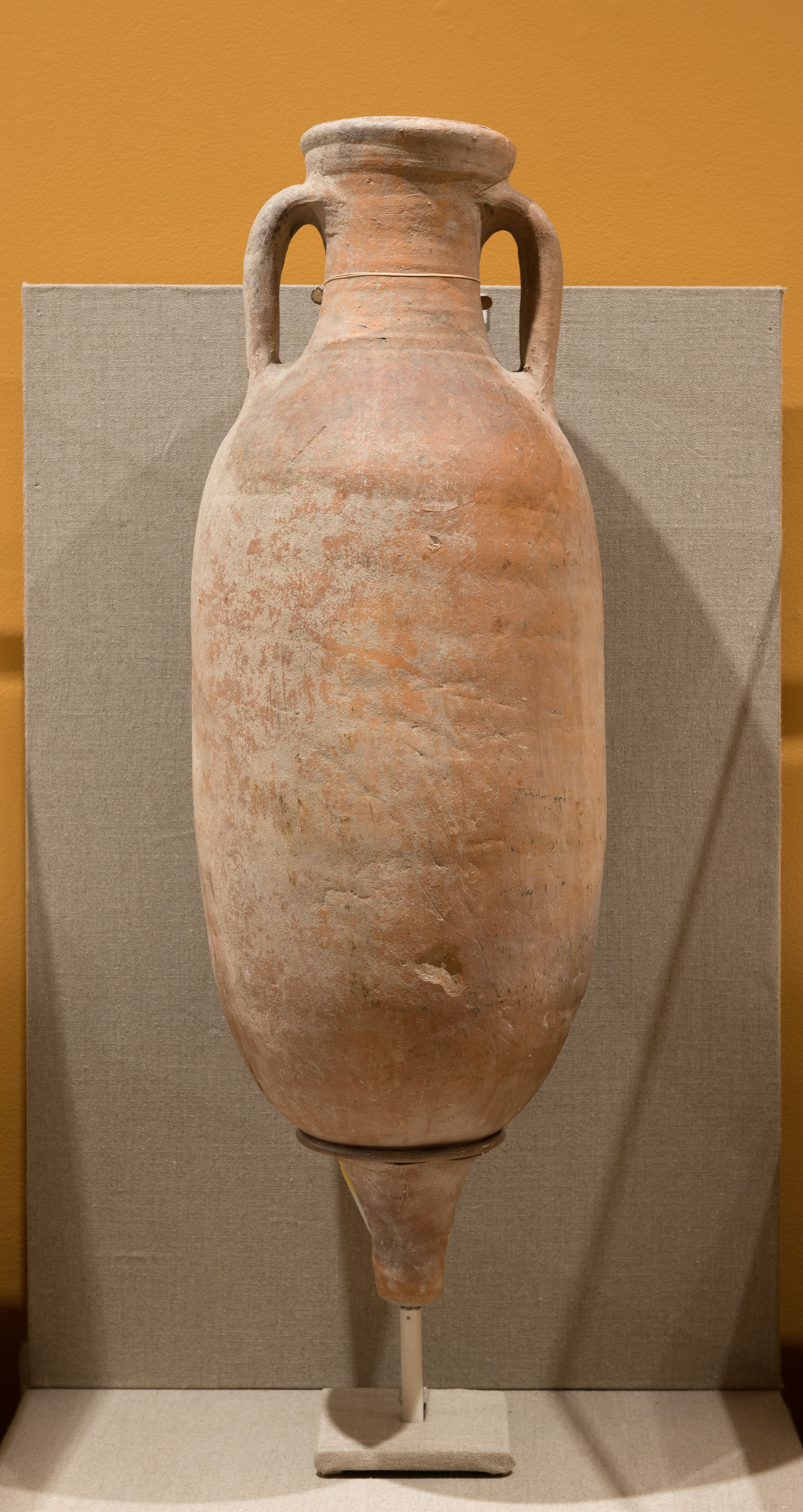

“It is the most spectacular and the largest villa site that has ever been found on the Bay of Naples,” says Barbara Kellum, a classicist and professor of art at Smith who helped bring the show to SCMA and served as its primary faculty advisor there. Oplontis, she says, is “on a far grander scale than Pompeii or Herculaneum, some would say an imperial scale.” That suggestion comes from the fact that a reference to Poppaea, wife of the emperor Nero (r 54-68 CE), is inscribed on a clay amphora found at Villa A (the largest of three discrete properties unearthed at Oplontis and one of two highlighted in this exhibition). While this is not definitive evidence that the villa belonged to her, Kellum cautions, “it certainly is grand enough for that to be a possibility.”

“It is the most spectacular and the largest villa site that has ever been found on the Bay of Naples,” says Barbara Kellum, a classicist and professor of art at Smith who helped bring the show to SCMA and served as its primary faculty advisor there. Oplontis, she says, is “on a far grander scale than Pompeii or Herculaneum, some would say an imperial scale.” That suggestion comes from the fact that a reference to Poppaea, wife of the emperor Nero (r 54-68 CE), is inscribed on a clay amphora found at Villa A (the largest of three discrete properties unearthed at Oplontis and one of two highlighted in this exhibition). While this is not definitive evidence that the villa belonged to her, Kellum cautions, “it certainly is grand enough for that to be a possibility.”

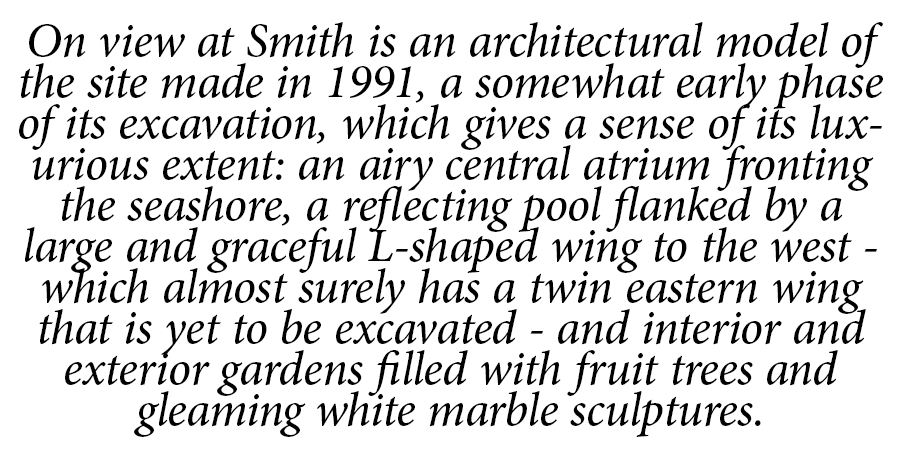

On view at Smith is an architectural model of the site made in 1991, a somewhat early phase of its excavation, which gives a sense of its luxurious extent: an airy central atrium fronting the seashore, a reflecting pool flanked by a large and graceful L-shaped wing to the west – which almost surely has a twin eastern wing that is yet to be excavated – and interior and exterior gardens filled with fruit trees and gleaming white marble sculptures. Many of the sculptures themselves grace the current exhibition, ranging from satyrs and goddesses – Aphrodite, coyly adjusting her sandal, and Nike, whose wings, sadly, have been lost to time, alighting gently on the tips of her toes – to portraits of unidentified contemporary people, including a sensitively rendered portrait bust of a young boy.

The architectural model also serves as compelling evidence for what is arguably the defining feature of Villa A: its extensive trompe l’oeil wall paintings. In the model, visitors can see in miniature what can otherwise only be experienced by visiting the site – the interrelationship of vast walls covered with fresco paintings depicting faux-architectural details: twining trees, vines, flowers and fruit, and a menagerie of creatures both real and fictional, from peacocks and songbirds to griffins, sphynxes, cherubs and hippocampi.

Center, Landing Nike, mid-First Century AD. Pentelic marble. Dowel holes in the shoulders show that this marble of the Goddess of Victory originally had separately crafted wings, perhaps of bronze. Scholars suggest that the figure was meant to be viewed from below.

While it was neither feasible nor desirable, of course, to transfer large portions of the actual painted walls into an exhibition space, the organizers have nevertheless made clever – and visually dazzling – use of digital modeling technology to reconstruct some of the villa’s walls and spaces. These are the creation of architect Tim Lydell, who has been with the Oplontis project since he was an undergraduate. Jessica Nicoll, director and Louise Ines Doyle ’34 chief curator at SCMA, praises Lydell’s “drafting skills, but also technology skills that were useful in helping to render, imagine and process information and understand what it was revealing about what the site looks like.”

Lydell was also the mastermind behind the modern recreation of a cubiculum, a small garden room that visitors can actually enter and listen to an audio track of trickling water and voices conversing in Latin. Mounted on these digitally printed reconstructions are actual fresco fragments from the site, giving visitors a sense of not only the vastness of the original project, but also the extreme care with which the ancient artisans created their designs to be a part of a harmonious whole.

Such wall paintings, as scholars of Federal-era America are well aware, became a huge influence on international art and design after the rediscovery of Pompeii and neighboring Herculaneum. “I come at this history largely through knowing its influence on British and American design in the Eighteenth Century,” notes Nicoll, whose credentials include the restoration of a classically inspired 1801 mansion in Portland, Maine. She says that seeing the frescos in person expanded her understanding of the influence of ancient Rome on English architect/designer Robert Adam and his later acolytes across the Atlantic.

Artifacts from the so-called Villa B – or more correctly, Oplontis B, since it was not technically a villa at all – shed light on the world of the Bay of Naples in the First Century in a very different way. For one thing, here where 52 bodies were found the stories of individual lives rise to the fore more so than in Villa A, which seems to have been uninhabited at the time of the eruption. There is some speculation that the dead, most of whom were found huddled together in the same general area, were attempting to flee and were waiting for a ship. The Oplontis sites, while now some distance inland, would have been right on the waterfront in 79 CE.

Ceiling fragments, some with vegetal ornament, AD 45-79. Fresco on plaster. Such “Fourth Style” fresco decorations—lighter, more ornamental and more concerned with the natural world than the heavier and more architectural “Second Style”—became a huge influence on European and American design in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.

Perhaps because of this many people had valuables with them – the jewelry they were wearing, like signet rings, along with the kinds of small, light, precious things one might grab in haste. Where frail human bodies succumbed to the heat and poisoned air, these precious objects survive in seemingly impossible perfection: a necklace with emeralds the size of gumdrops, gleaming gold and silver coins, earrings with pearls dangling like castanets.

One meaningful example is a seal ring stamped L.CRAS.TERT, a shortened form of the name Lucius Crassius Tertius. Such rings were used for signing and sealing documents written on wax tablets. They had an exclusively business-related function. During a time when the social codes of those who lived in villas demanded that they give no outward sign of actually working for their wealth – a First Century Roman version of the old chestnut that a British gentleman never knows his bank balance – such a thing would only have been used in a commercial center like what we understand Oplontis B to have been. Scholars speculate that Lucius was probably a former slave who had learned a trade during servitude and then earned his freedom, as many did. He may well have been the proprietor of the site, which seems to have incorporated aspects of wine production and distribution as well as other shops and businesses, along with second-story residences.

It was from one of those residences, Kellum suggests, that an ornately decorated metal strongbox fell as the weight of the ash caused the building to collapse. A strongbox was a “demonstrable symbol of family wealth. Especially in houses of freed men, they were very prominently on display,” she says. This is not something one would likely have seen in a patrician villa. The strongbox excavated from Oplontis B is significant partly because it would have been so deeply significant to its owner in 79 CE, but also because it was already an antique by then.

The inscription crediting three Greek artisans with its creation dates from between the First and Third Centuries BCE, so it was already at least 200 years old when Vesuvius erupted. The artisans embellished the strongbox with an elaborate inlaid silver and copper head of the satyr Silenus surrounded by twisting vines, as well as with several sculptural elements – bronze dogs’ heads and a duck, among others – that would together have contributed to a complex locking system, requiring specialized knowledge to undo.

We see the box in the exhibition today as a solid, intact piece of workmanship. In fact, it was found shattered, with its wooden core either burnt or rotted away. It has been painstakingly excavated and studied – along with the coins, jewelry and fragrant unguents found nearby that were presumably its contents – and subsequently reassembled. This exhibition and the archaeological project that it celebrates, then, strive to do for the whole of Oplontis what has been done for this strongbox. In so doing, it begins to unlock and reveal the secret histories that it contains.

The Smith College Museum of Art is at 20 Elm Street at Bedford Terrace. For information, www.smith.edu/artmuseum or 413-585-2760.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is a writer, editor and independent art historian in South Portland, Maine.