What are you drawn to when you think about the French Revolution? Justice for the working class? The Bastille? The beheading of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette? The rise of Napoleon? Let us offer another perspective: the personal letters from the Comte D’ Artois, the future King Charles X of France, as he fled his country during the revolution and watched helplessly as his brother and sister-in-law met the cold judgment of the people. A trove of 75 letters from the future king have risen from a basement floor to the top of the podium at Freeman’s January 30 sale. While it takes “leaks” in today’s age to understand where a politician’s mind runs, here we have the raw, uncut personal letters from a count and future king during one of the most important moments in French history – and they are unsparing. Antiques and The Arts Weekly spoke with Roger Ross (RR), the consignor, as well as Freeman’s specialist Raphael Chatroux (RC) to learn about their history and context.

What are you drawn to when you think about the French Revolution? Justice for the working class? The Bastille? The beheading of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette? The rise of Napoleon? Let us offer another perspective: the personal letters from the Comte D’ Artois, the future King Charles X of France, as he fled his country during the revolution and watched helplessly as his brother and sister-in-law met the cold judgment of the people. A trove of 75 letters from the future king have risen from a basement floor to the top of the podium at Freeman’s January 30 sale. While it takes “leaks” in today’s age to understand where a politician’s mind runs, here we have the raw, uncut personal letters from a count and future king during one of the most important moments in French history – and they are unsparing. Antiques and The Arts Weekly spoke with Roger Ross (RR), the consignor, as well as Freeman’s specialist Raphael Chatroux (RC) to learn about their history and context.

Give me the background. Where did these come from?

RR: I’ve been with my partner Eric Bongartz for 14 years. So about 16 to 18 years ago, Susan, our good friend who passed away about five years ago, was selling her house in Orient, Long Island. We have a house on Orient Point, and we also lived near each other in the city. She was very eccentric – she sold and gave a lot of things to Eric when she sold her house, these included, and she gave a large amount of her things to the Animal Rescue Fund down here. Her predeceased husband, who died 15 years before her – his family owned a rare manuscript company, Madigan Rare Books on 5th Avenue, for generations in New York. I have a compendium of all the different letters that they held at one time: from Marie Antoinette, Washington, Lafayette. They were selling them in 1920 for $10, $12, $15.

What was Susan like?

RR: To give you an idea of how cool she was: her husband won two Emmy awards. We shared a cleaning lady, who is also a friend of ours. I went to her house one time and I said, “Is that an Emmy on your piano?” And she goes “Yes! Susan gave it to me, she said it was her husband’s.” Next time I saw Susan, I asked her why she gave the cleaning lady the Emmy. And she said, “Roger, well I have two!” So that kind of paints a picture of the kind of wonderful, witty, great friend she was.

Where were you when you found the letters again?

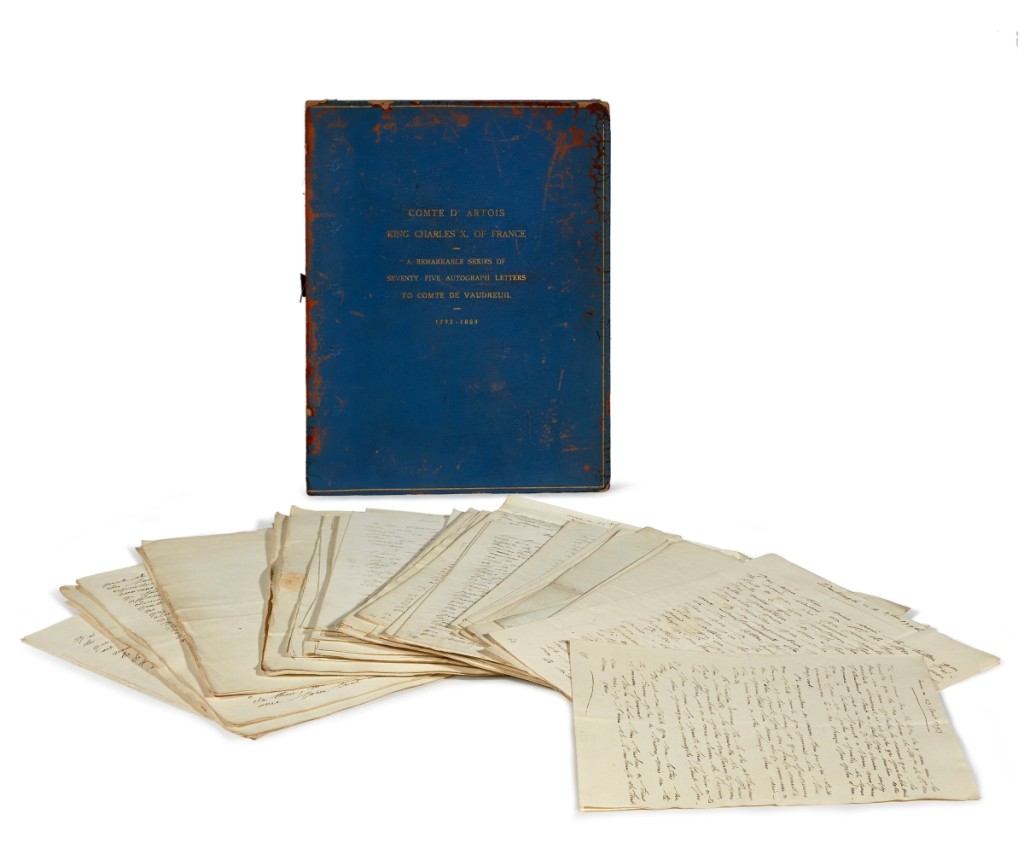

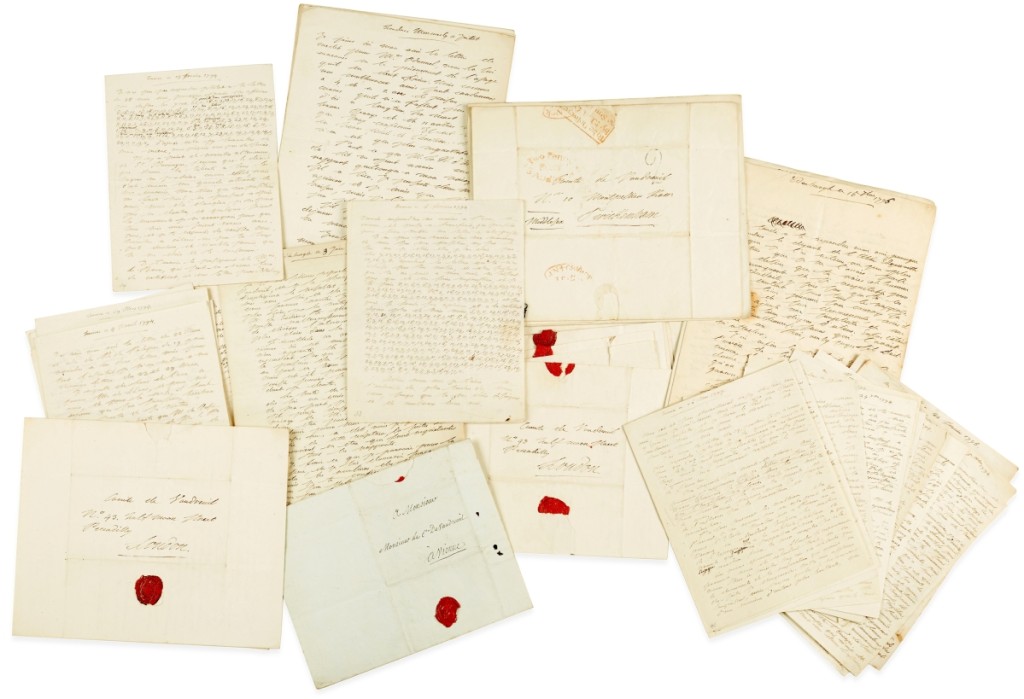

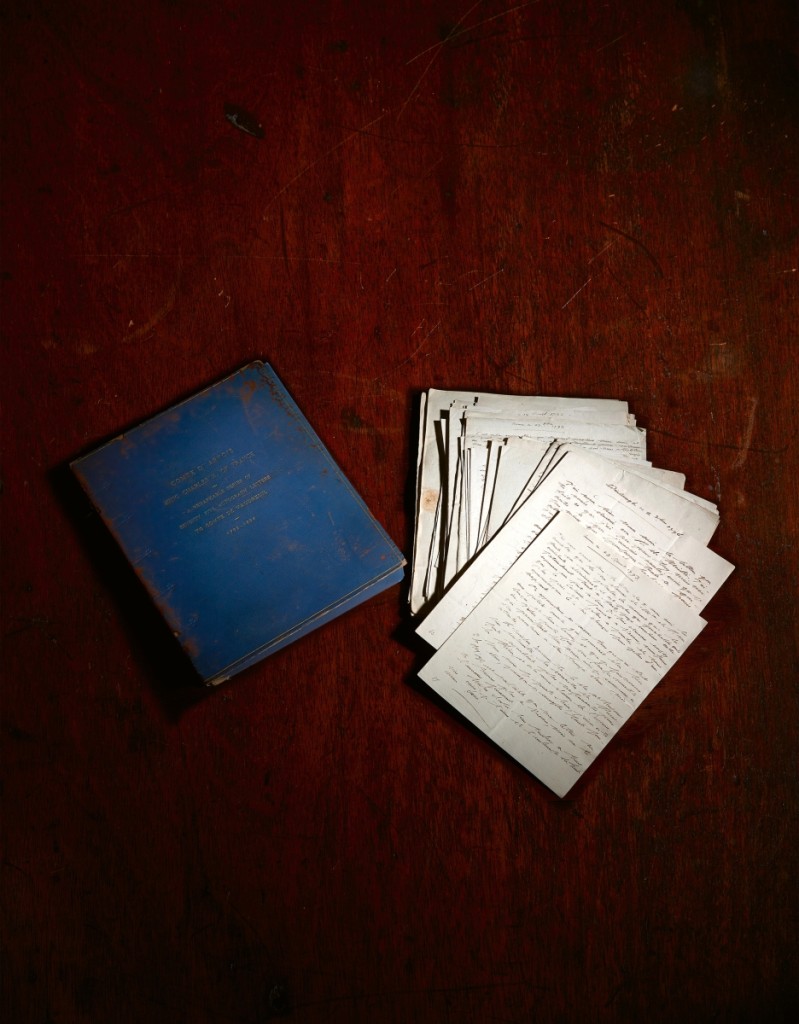

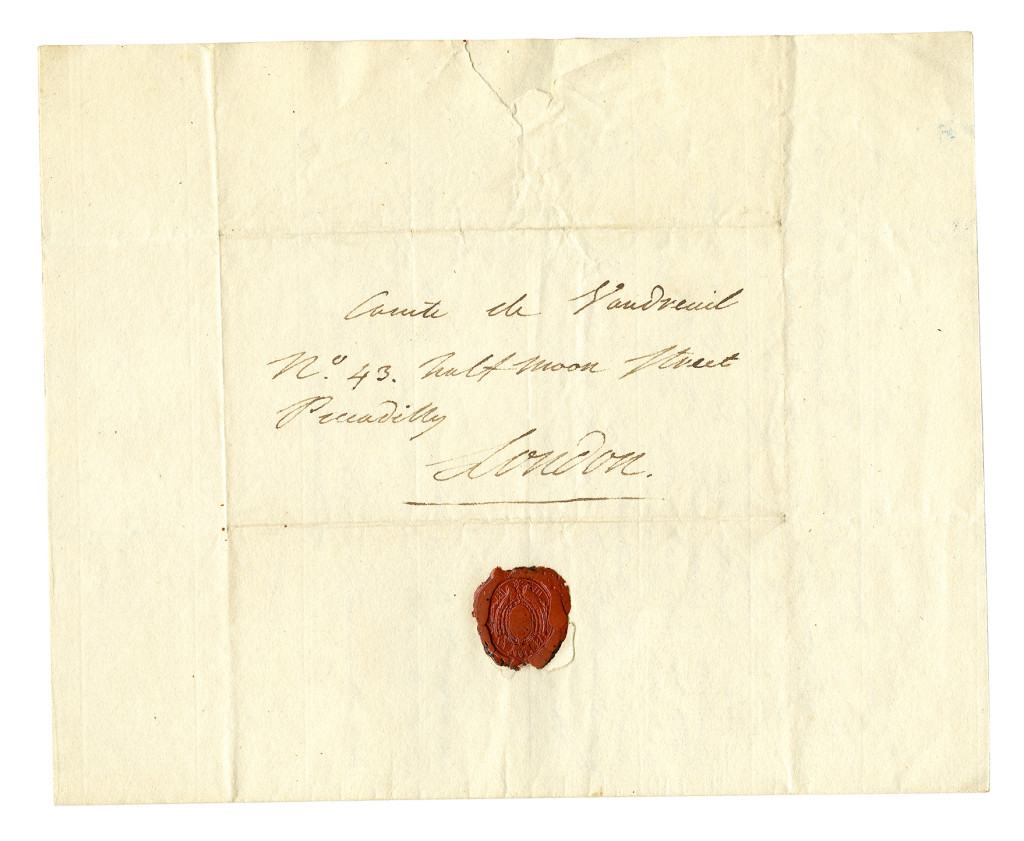

RR: So these letters were laying on the floor in our basement – on the floor – in a plastic milk crate, and Eric and I – Eric has the biggest heart in the world – our friend is a manic French wine collector, and he ran out of room in his cellar, so we gave him half of our cellar. So we have 100 cases of his wine down there now. And one day I said, “We’re running out of space, so let’s clean a little.” So I picked this crate up and put it on the washing machine, and on the top were two signed books from Theodore Roosevelt. Two volumes from African Game Trails, editioned 300 of 500. And I looked at Eric and I said “Do you know what these are?” And he remarked they were ruined and they needed restoration and they might be worth nothing at all and who knows if they’re real? Well, I looked at them and thought they were real. And right beneath them was this beautiful blue sleeve, and stamped on it in gold lettering was “Comte D’ Artois / King Charles X Of France / A Remarkable Series Of Seventy-Five Autograph Letters To Comte De Vaudreuil / 1792-1804.” I opened it up and on the very top there were typewritten pages that had translated the letters, and it was dated 1920. I open it further and there are these magnificent letters in crème ivory paper. I would say 5-by-6 or 5-by-7 inches. Some of them had 30 lines with the most magnificent penmanship, very minute, written by some very educated person, but not necessarily a king. It’s not bombastic, it’s not huge, it’s not on big paper. So I was just amazed, the majority had red wax seals about the size of a silver dollar. And I held one up to the light to see a watermark, and it had one.

Then what?

RR: I sent them down to Alasdair Nichol at Freeman’s. And then specialist Darren Winston and I had an appointment to meet. We met at one of the clubs in New York City, and he had his French colleague with him, Raphael Chatroux, and they looked at them and said they looked pretty amazing, but they needed to do further work. They got back to me about six weeks later and said “Roger, we have amazing news for you. Not only are they authentic and great, but they’re better than we thought. We think there will be a lot of activity on these.” The year 2020 is the 250th anniversary of the wedding of Marie Antoinette and the future King Louis XVI.

So what stuck out to you about the letters?

RR: I have the 1920s translations here. On November 19, 1792 – this is the translator talking about these letters – Charles, the Comte D’ Artois, had already passed several months in Russia, and he’s talking to the Comte de Vaudreuil, he says, and this isn’t rote, “You have no conception of this country and the people. The people and the soldiers are perfect because they are slaves, but the great lords are vile, hard and grasping.” This sends a double message; he’s saying they are slaves but he enjoys them as slaves, and the nobility – they are “vile, hard and grasping. They lick the feet of the favorite, but the favorite is charming because he is sympathetic to us.”

Then another letter: “It is more appalling than ever. The unfortunate king is being tried at present and beyond a doubt will be condemned. Perhaps the Convention will wish to keep him as hostage, but it is still very doubtful that the Convention can shield him from the rage of the people.”

He knew what was coming.

RR: A letter Charles sent after he learned of Marie Antoinette’s fate: “The cruel death of the queen..I hope for nothing but vengeance.”

And this stands in contrast to what the queen said in her last letters. “Let my son never forget the last words of his father, which I repeat emphatically; let him never seek to avenge our deaths.”

RR: Exactly; she said just the opposite. There’s also a quote where Charles fears for his sister, Madame Elizabeth [Élisabeth of France.] “They wish, it appears, to marry the little Madame with a sans culotte,” those are the revolutionaries. Then he goes on “Alas my friend, it is 15 years since we fled our country to escape useless death. Life was very dear to me then; now I only live to ask God to cut short my punishment and forgive me the happiness I enjoyed..” It’s so poetic, it’s tragic.

My understanding is that even during the negotiations with the revolutionaries, Charles was still defiant, even though he was completely bankrupt.

RR: Charles was unforgiving. Louis XVI once told him he was more of a monarchist than a king.

You have a French connection, too?

RR: My mother was a translator in the French Resistance and to an American General at the close of the war at Orly airport. And then there’s our house here in Kerhonkson, N.Y. I’m living in one of the oldest French Huguenot houses probably in existence in the United States. The founder of my house, Jacobus Depuy-Dewitt, they were the royal guards to the king of France in Fontainbleu. Sometimes, strange oddities connect all of us.

You’re donating some of the proceeds from the sale?

RR: Ten percent to my good friend Dr Mehmet Oz for HealthCorps – that’s his foundation that he founded to end obesity and diabetes in our youth and to work with behavioral health issues. Another ten percent to the National Ataxia Foundation, and that is a disease that my partner, Eric, suffers from. 150,000 people suffer from this, and that’s considered a small audience to the pharmaceutical industry, so they don’t work on it as hard as other diseases that afflict millions. It’s similar to Parkinson’s in that it diminishes the mobility of people. So that will be a nice opportunity to start with those two things. We don’t know what it will go for.

Is the French Revolution still modern?

RR: Yes, you can make comparisons to situations around the world today and in our own country. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

What’s the context that these letters are written in?

RC: These are letters that Charles, the brother of King Louis XVI – known as the Comte D’ Artois, and who will become the future King Charles X – wrote to his best friend, the Comte De Vaudreuil, Joseph Hyacinthe François de Paule de Rigaud, as he was in exile. It really starts a couple of months after the Storming of the Bastille and then it goes deep into the year 1805 – a year after Napoleon I’s coronation. The letters are written to Vaudreuil from pretty much everywhere in Europe. You have letters written and sent from the first place he visited after he left the Palace of Versailles, Savoy, then you have Italy, Germany, Prussia and Russia. The last letters are written from England, and especially London, where Charles sought refuge before going back to France in 1814.

These letters are written as Charles was fleeing the kingdom. Even if the Parisian people were not really after the family, per se, Charles was not really liked within the society, so his brother feared for life and asked him to leave the country. Until October of 1789, only a few members of the royal family were still at Versailles; the rest of the extended family had all left. It was only in October of 1789 that the king was withdrawn from the palace and sent to the Tuileries Palace in Paris, where the crowd could more easily watch him and see what he was up to. By then, Charles had long gone and was traveling all around Europe, where his cousins or his brother-in-law and all sorts of members of the extended family welcomed and allowed him to stay for a certain amount of time.

How many royal contemporaneous accounts of the French Revolution exist?

RC: You have quite a lot of correspondence out there that are contemporary to the Storming of the Bastille, but you don’t often find that many letters at once from a member of the royal family itself. Other similar letters can be found in museums or palaces all around Europe. These letters are therefore quite unique in today’s market. They are also fascinating in that they were written by the most outspoken member of the royal family. Charles was not educated to reign. He was the youngest brother of Louis XVI and enjoyed a lot of freedom during his teenage years. To be able to read his words, unfiltered, is a pure privilege.

At the time, Charles was not regarded well by the French people.

RC: At the time, no, because he spent a lot of money and supported members of the government that were not too popular in Paris, such as Calonne, who implemented measures that ended up privileging the richest. Charles was also very young at the time of the revolution, so he didn’t really have the maturity that Louis XVI had. He liked to party, to go out, he had a lot of money to spend, and he did it in front of everyone. He was not thought to be overly sensitive to the poor and appeared selfish.

Let’s talk about the letters.

RC: In my opinion, you have three different developments within the 75 letters.

The first letters, up to the 1790s, echo Charles’ questions and fears. He is wondering what to do in order to save his family and get them back onto the throne. The letters are extremely personal and reflect Charles’ ongoing interrogations. What is particularly interesting is to compare Charles’ attitude with his friend’s. In his response letters to Artois, Vaudreuil confesses he does not agree with his attitude. Charles is much more vocal in his desire to save his family with the help of other European courts. But his friend, who was always thought to be a liberal, believes that it is not the best idea; asking for the other courts’ help would be considered a treason to the French people, who would feel attacked by foreign countries. Vaudreuil always advised Artois to remain close to the frontiers to be able to get back to France if needed. His theory was to be reactive, not proactive.

The second development is the most dramatic one; it corresponds to the years 1790-94, where Artois understands that there is no going back, nor stopping the revolutionaries. His letters do not talk about action anymore, but revenge. He already knows restoring the monarchy will be difficult and prefers to linger on what he will do to the criminals that executed his family. To me, those letters are actually the most interesting ones, because it is the story of a man whose world is completely crumbling around him, whose brother is about to go on trial, then die in the most tragic way. Of course, for the reader, it is equally sad to witness Artois’ rage and despair, but it also makes the correspondence stronger: the most important page of French history is told by a man with completely unfiltered words and mind.

The third development revolves around the later letters, after the king and queen died, and it is becoming clear that Charles and his family will not get back to France anytime soon. There is more bitterness in those letters, with Charles commenting on France’s situation and deploring its lack of splendor. Those letters are less personal and more political in a way. Charles has been out of France for a long time at this point; they reflect his views on French politics and main characters, including Napoleon Bonaparte. Charles loathes Napoleon and somehow adopts the English attitude towards France: the man needs to be stopped.

Do we learn anything new from these letters? Any new evidence?

RC: These letters were already studied and transcribed by a Leonce Pingaud in the late Nineteenth Century. The letters were therefore known, and we were able to compare the published version with the original letters. So, you don’t really learn anything new per se. But the feeling of touching a part of French history, physically speaking, is a unique feeling. It is also interesting to be able to study Artois’ handwriting: beautifully preserved, elegant and flowing.

What is your favorite letter?

RC: The several letters in which Artois discusses the king’s trial are a strong read. Yet my favorite letter remains the one in which he discusses the death of the Duchess of Polignac to his friend Vaudreuil. The duchess was an important character at the court, the personal friend of Queen Marie Antoinette and the cousin of Vaudreuil himself. The three of them were very close, and the news of her death was a real shock to Charles. In a way, he expresses even more sadness to her passing that to the execution of Queen Marie Antoinette.

Do you have any institutional interest?

RC: We have received some interest, but it is still a bit early to tell. We corresponded with some interested parties in Europe, and are hoping to attract institutional attention.

Was there anything that you were surprised to see in the letters?

RC: It’s a segment of French history that French people think they know very well. I was quite happy to read them, because if you think of the French Revolution and the royal family as a family in a TV series or a sitcom, Charles X is not really your favorite character, so there’s not a lot of sympathy for him. He’s quite narrow-minded and privileged. Of course, he’s the little brother, so he thinks everything is due to him, he’s not very respectful of his brother, he always wants to be king but does not necessarily know how to lead; he never went on the battlefield, for example – he’s a little bit of a brat. So, it’s interesting to see what he has to say; his speech is completely free, as opposed to the very politically correct letters of his older brother. It is also quite fascinating to follow his chain of thoughts and understand what he thought was best to save his family and then see revenge. You understand he did not make the right decision, which he realized, too, in the end. It makes him even more human, I believe, as he reacted on a very personal level.

In the great drama, is this where he matured? His coming of age?

RC: To an extent. When the revolution happens, it really is a shock for everyone. Yet Charles is almost automatically thinking of a counter-offense, and then revenge, so he’s still optimistic he will get back to France in the end. I believe the real wake-up call for him happened after his brother was sentenced to death and his nephew died: he was then second in line to the throne and probably felt he had something to do.

Additional lot information can be found here.

-Greg Smith