A herd of spotted deer, animals common in Chinese art and literature, roam this verdant landscape. In Chinese, “deer” sounds like the word for official rank and salary, so the phrase “many deer” conveys a wish for prosperity. Deer also symbolize longevity, as they often accompany Daoist deities or immortals in art. “Many Deer,” China, Ming–Qing dynasties (1368-1911). Handscroll, ink and color on paper. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 33-649. Courtesy The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

By Karla Klein Albertson

KANSAS CITY, MO. – After a pandemic postponement, a brilliant collection of “Lively Creatures: Animals in Chinese Art” is on view until September 4 at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. The show is the creation of Ling-en Lu, its associate curator of Chinese Art, who – when asked why in a recent interview – replied: “A pretty simple answer to that question – I wanted to do this exhibition because I like animals. Animals actually appear in Chinese art throughout its history from the beginning several thousand years ago to contemporary times.”

As in many cultures around the world, animals often stand in for human traits – everyone knows what it means to be a tiger or a bear or a peacock. In this way, creatures can become useful characters to illustrate human ideas. With these elements in mind, Lu set out to present her concept as a serious theme for an exhibition while retaining the playful aspect. She noted that there had been a 2019 show at the National Gallery of Art in DC on “The Life of Animals in Japanese Art.”

A trip to the local zoo confirmed the curator’s plans: “There were so many animals I could see. The polar bears moving in the water, colorful birds – and I thought, why not do an exhibition of animals in Chinese art, we have plenty of art works to choose from.”

And that, of course, is a major understatement for the Nelson-Atkins, which has one of the richest collections of Chinese art in the Western Hemisphere – more than 7,000 works. How these objects were gathered is well known to anyone who collects or studies Asian art, but worth repeating.

In the harsh days of the early Depression, this museum with a dual name was established by the generosity of two people. William Rockhill Nelson was a newspaper founder and real estate developer – the expected sort of donor. But the other was a woman named Mary McAfee Atkins, a retired school teacher and apparently successful real estate investor who left part of her estate for this purpose because she loved art. The museum with its classical façade and marble halls opened in December of 1933.

This badge depicts a Chinese dragon, a mythical creature that changed over centuries and came to symbolize imperial power. Here, it has a horned head, sharp fangs, five claws and an agile serpentine body. The dragon’s magical powers allow it to fly and dive deep in water. The badge, finely embroidered with luxurious silk and gold foiled threads, could only be fit for an emperor or heir apparent. Dragon Badge, China, late Ming dynasty (1552-1644). Silk and metallic thread embroidery. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 41-15/19. Courtesy The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

At that moment, when the museum was buying, many people were selling. Gathered over the decades, the Nelson-Atkins has a permanent collection with stars in every department -from a striking ancient Egyptian portrait from the Twelfth dynasty and Caravaggio’s “St John the Baptist” to the Claes Oldenburg’s “Shuttlecocks” that landed in the sculpture garden. The Burnap Collection of pre-Industrial English Pottery is the best outside Britain.

The Asian art collection was a special case, however. Chinese art scholar Laurence Sickman was on the ground in China buying art during a period of great political turmoil in the country, when many were parting with treasures to raise money. Some of the best paintings were reportedly acquired directly from Emperor Pu Yi, the last monarch of the Qing dynasty. On his return to Kansas City in 1935, Sickman became curator of Oriental art and eventually director of the museum in 1953. One incredible survival that entered the collection in 1934 is the magnificent Twelfth Century “Guanyin of the Southern Sea” – a painted wood sculpture almost 8 feet tall that is one of the best-known figures in Chinese art.

So, Ling-en Lu was able to dive into the fabulous depths of this collection and bring out fragile treasures rarely on display. There are scrolls depicting animals that have been in the collection since the museum’s earliest days and intricately embroidered and woven badges of rank. Longing for a good rub are small jade animals from a scholar’s desk and two pairs of porcelain rabbits that children will long to play with.

For light sensitive objects, the curator had exposure rules to observe: “This was a reality I had to follow, which limited my choice. Fortunately, there were pieces from the textile collection which hadn’t been on view for a long time.” And after this run, they will disappear back into storage for another ten years.

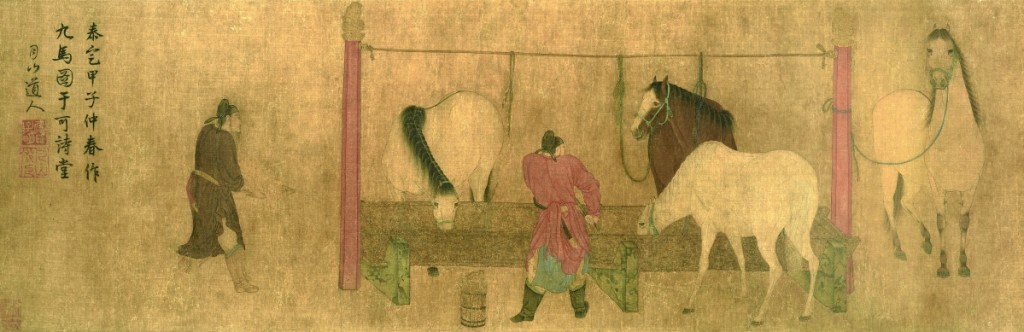

The scroll depicts stable workers feeding and grooming nine royal stallions in preparation for a parade. The imperial court treasured horses as pets and as emblems of royal power, importing strong steeds from Central Asia to serve in battle. Ren Renfa’s sure hand and fine line work made this detailed painting an important model for later followers. “Nine Horses” by Ren Renfa (Chinese, 1255-1328), 1324. Handscroll, ink and color on silk. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 72-8. Courtesy The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Several major themes are explored from animal roles in stories where they reflect human characteristics to animals’ importance in Buddhist art. Least known to most viewers will be the significance of the seldom-exhibited fabric badges indicating rank and power, which were worn over formal court dress during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911).

These badges – a fascinating study for students of needlework – depict both real and imaginary animals and reflect the image the office wants to project. No surprise the great horned dragon – that creature so beloved of fantasy enthusiasts – was the symbol of imperial power.

Military officials naturally wore badges with fierce beasts – leopards and lions and even unicorns – but they rarely survived because the spot where they were worn was right where their owners might receive the fatal blow. Civil officials, on the other hand, get birds which have splendid plumage but do have an awful lot to say.

With these images of colorful creatures, Ling-en Lu has designed the exhibition to appeal to many types of visitors: “First goal, when they come into the gallery, is that they appreciate the artwork, no matter whether they understand Chinese art or not. They can see the beautiful paintings or textiles. I wish everyone can appreciate Chinese art, so my attention is to present the exhibition to everyone, not just Chinese specialists.”

Among the animals, she points out some true rarities like the Dragon badge from the late Ming dynasty (1552-1644) supposedly used by the Emperor. Another important exhibit is the “Nine Horses” scroll painting (1324) by the artist Ren Renfa; there are less than ten paintings by the artist. A lampas brocade textile – “One Hundred Birds in a Garden” from the Ming dynasty – displays a complex weaving technique imported into China.

When displayed on a shelf or desk, these rabbit mates would bring love to a family. In Chinese art, rabbits are auspicious for their gentle nature, and Chinese folklore tells of a rabbit that has lived on the moon for thousands of years. The slim green collars of these rabbits suggest that they represent domestic pets. Pair of Rabbits, China, Qianlong period (1736-1795). Biscuit porcelain with glazes and enamel decoration. Purchase: The Mrs David T. Beals Sr Fund, F75-55/1, 2. Courtesy The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

She continues, “Then, I want them to know about the cultural meaning of animals in Chinese art.” In other words, what people viewing the artworks at the time of their creation would associate with the animals depicted. For example, the silver pheasants on a Ming dynasty scroll are associated with literary talent and trustworthiness.

A personal favorite of the curator is a scroll from 1427 depicting a little dog under some bamboo; the scene contains some tricky word play for the characters for bamboos and dog combine to form the character for a smile or joke. This exhibition of lively animal images reveals multiple layers of meaning on further contemplation.

Anyone fortunate enough to travel to the Nelson-Atkins in the next few months can also catch “Weaving Splendor: Treasures of Asian Textiles” through March 6. Among the fabrics from many countries lurk more animal images, including a Chinese “One Hundred Cranes Imperial Robe” from the Qing dynasty that was an early acquisition of the museum.

For the entire intriguing story of the institution’s beginning, read The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (2020). Find the bookshop and a visual introduction to the entire collection at www.nelson-atkins.org.

Speaking of animals, Chinese New Year and the beginning of the Year of the Tiger falls on February 1. There are many traditional celebrations, but public parades with dragon and lion dances are a chance to see these creatures at their liveliest.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is at 4525 Oak Street. For information, 816-751-1278.