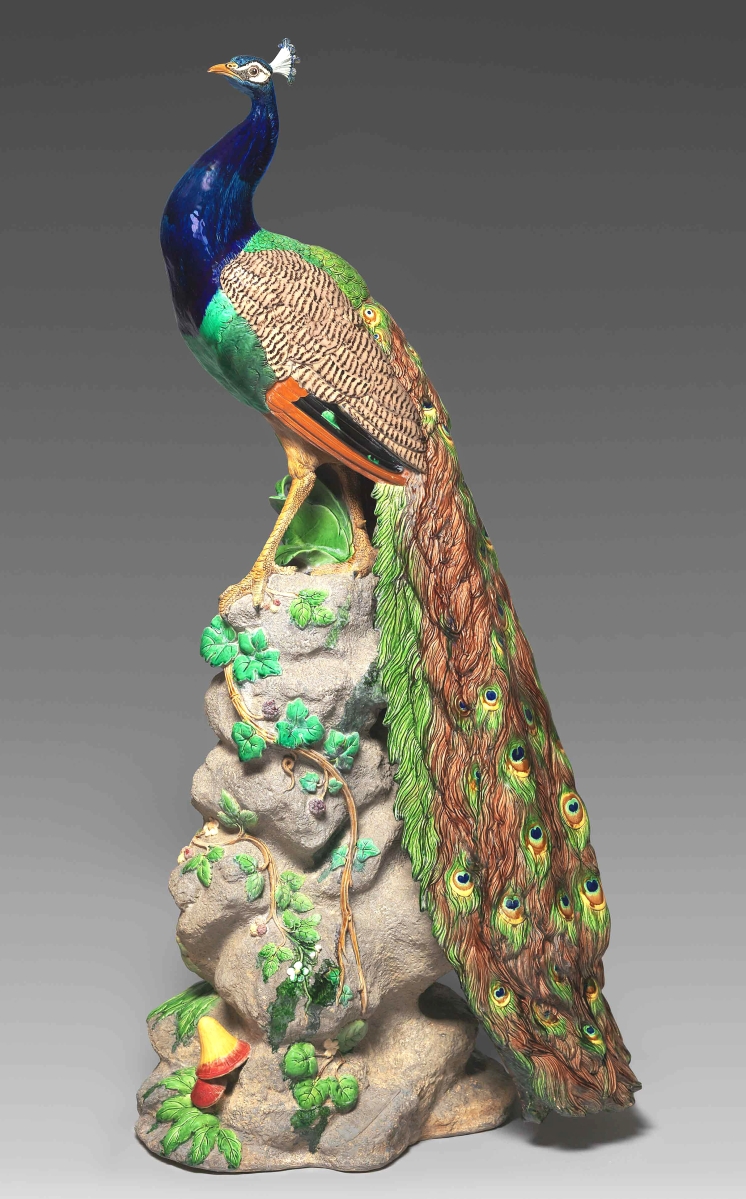

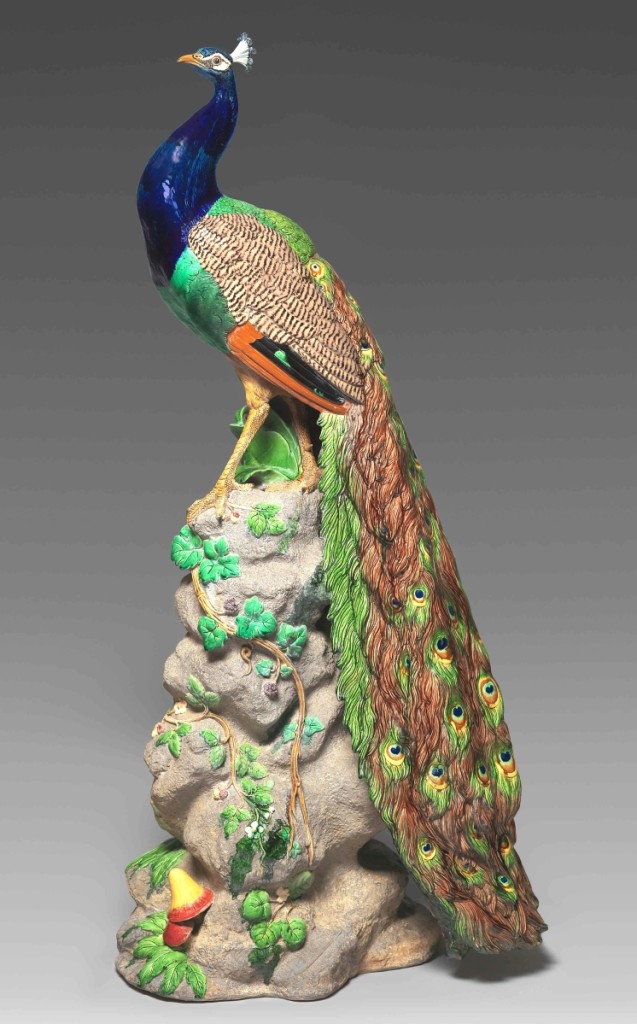

“Minton stretched the boundaries of ceramic production with life-size animals,” stated Weber. The peacock “makes eye contact with you. You just feel his presence.” Peacock designed by Paul Comoléra and manufactured by Minton & Co.; designed circa 1873, this example made 1876. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 59-7/8 by 27½ by 17¼ inches. The English Collection. Photograph Bruce White.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

NEW YORK CITY – A lizard hitching a ride on a nautilus, a ghostly lady’s hand holding a pineapple, a haughty peacock perched on a towering rock pile – these marvels and more occupy the wonderland “Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850-1915.” Opening at New York’s Bard Graduate Center on September 24, the innovative presentation – bold as the ceramic itself – is a welcome counterpoint to the diet of Modernism dominating design exhibitions of late. The major research and reappraisal initiative organized by Bard Graduate Center and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore challenges conventional “wisdom” about majolica, a medium long maligned in the arts world. After its New York debut, the exhibition journeys to the Walters Art Museum and to the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, U.K. Acolytes of Midcentury Modern are advised to repress their asceticism when entering this lush, eccentric realm.

Dr Susan Weber, founder and director of the Bard Graduate Center, and Dr Jo Briggs, the Jennie Walters Delano assistant curator of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century art at the Walters Art Museum, have curated a brave exploration of the quintessentially Victorian ceramic. Weber stated, “the exhibition is the culmination of an international research project undertaken over several years that continues BGC’s tradition of identifying under-recognized and undervalued areas of scholarship within Nineteenth Century decorative arts.” She hopes it will spark “renewed appreciation of Nineteenth Century ceramics in general and majolica in particular.”

Within the history of world ceramics, the word “majolica” can refer to different types of pottery made at different times and in different places. Here vibrantly colored, glossy lead glazes are the main event, with the ware’s sculptural quality achieved primarily through casts and molds a contributing characteristic.

In conversation, Weber asserted that majolica “is arguably the most important ceramic innovation of the Nineteenth Century.” It illustrates the rampant eclecticism of the era, according to the lead curator, with inspiration drawn from Classical, Renaissance, Asian and Gothic styles. She further observed that while this project focused on majolica manufactured in England and the United States, the ware was made in many other places. “It really was a mania,” declared Weber.

Minton & Company’s artist-potter-chemist Léon Arnoux developed the ceramic which came to be called majolica. The famed Stoke-on-Trent firm ostensibly introduced it at the 1851 London Crystal Palace Exhibition, the first World’s Fair. Majolica enjoyed an impressive British upper- and middle-class following through the 1870s. Even as Minton continued to reign as majolica’s premier maker – with Wedgwood and George Jones among the potteries also creating highly artistic pieces – other factories jumped in to provide less costly majolica. British firms supplied markets abroad as well as at home, producing “niche” items, such as cuspidors for Americans, to meet consumer preferences in various countries.

The Trenton, N.J., factory copied one of its favorite motifs, a bird flying over a flowering plum branch, from the Staffordshire-based firm of Shorter & Boulton. “Merry Xmas And Happy New Year” plate by Eureka Pottery, 1883. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 9½ inches diameter. Private collection, ex collection Dr Howard Silby. Photograph Bruce White.

While top-drawer British factories employed sculptors and painters to help create art-quality showpieces of limited number while also manufacturing more commercial lines, factories in the United States concentrated on the commercial, often imitating models fabricated by other potteries. James Carr’s New York City Pottery and Griffen, Smith & Co. of Phoenixville, Penn., began to make majolica in the 1870s, with factories in Trenton, Baltimore, East Liverpool, Ohio, and Peekskill, N.Y., following soon after.

As Victorians were swept away by the spirited art-industrial earthenware, subsequent generations of Arts and Crafters and Modernists rejected it with equal force. Majolica’s demise is charted here, with factors including the growing realization of the danger of lead glaze in the workplace, millions of cheaply turned-out pieces flooding the market by century’s end, and, of course, changing tastes. The epochal earthenware was too iconic, if there could be such a thing, and critics took aim at majolica items like clay pigeons at a trap shoot. For example, in 1904 ceramicist Mary White penned the following burn: “time was when majolica jardiniéres…, with their high colours and glassy glazes, were things to be desired. Happily, they are going the way of plush-covered ‘suites’ of furniture and crazy quilts.” In 1934, London’s Victoria & Albert Museum transferred consequential world-exposition pieces to the Stoke-on-Trent museums in an anti-Victorian design purge, an act that epitomized the animus majolica provoked during the Twentieth Century. As a rule, art museum curators continued to hold majolica in low esteem and did not collect or exhibit it.

Weber recognized with appreciation majolica collectors Philip and Deborah English and the late Joan Stacke Graham as early supporters of the exhibition. “We couldn’t have done the project without collectors frankly because museums have very little of it. And, in particular, American collectors helped us because they are the ones who founded the Majolica International Society and they are also the ones with amazing collections.”

When describing the seriousness of Majolica International Society members, Weber made clear that “without them there would not be this tremendous interest now and the ability to do a show like ‘Majolica Mania.’ They really lit the fire.” To learn more about the society’s programs and online resources, visit majolicasociety.com.

Dr Laura Microulis, BGC research curator and co-project director for “Majolica Mania” along with Earl Martin, summarized the project’s contributions to the fields of ceramics, business and labor history: “Through our in-depth archival research we have significantly expanded the majolica narrative beyond Minton and Wedgwood to include some of the lesser-known Staffordshire makers, many of which produced prodigious amounts of the ware and engaged in an active export trade. In addition, we have accurately documented the US potteries that made majolica – highlighting the critical impact of English immigrant craftsmen and the transfer of capital and skills on the burgeoning American ceramics industry. Until now, this scholarship had not been undertaken.”

This object is stamped: “Manufactured By W.T. Copeland & Sons Solely For J.M. Shaw & Co. New York.” The firm, located in the town of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, made the model in both bone china and majolica. Centennial Memorial vase by W.T. Copeland & Sons, circa 1876. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 9¾ inches high. Joan Stacke Graham. Photograph Bruce White.

Incorporating 350 objects, the exhibition chronicles majolica’s makers and uses, design sources and applications, artistic glories and occupational health hazards, and ups and downs in popularity. Majolica mavens will relish the factory-by-factory line up of products and design borrowings. Those intrigued by the natural world will see how majolica emerged at a time when collecting exotic plants, tropical fish and seashells was all the rage. Fans of historic interiors will enjoy learning about majolica in the home and its ties to the proliferation of dining and horticultural forms and equipment during the Nineteenth Century. World’s fair devotees will appreciate discussion of majolica marketing through international expositions, an industry constant. At these Olympics of merchandise, manufacturers and retailers wowed attendees with exhibition pieces, sold commercial wares, and competed for quality awards.

But all this beauty and whimsey had a horrific side. The lead in majolica’s glaze, which allowed for the firing of bright colors at low temperatures, endangered workers’ health. Weber explained that she and her colleagues could not show the remarkable decorative art without recognizing the lives lost in creating it. They needed to acknowledge that children, women and men “worked in cramped and unhealthy conditions, at kilns fired by coal with dust everywhere, and with a glaze full of lead which attacked the central nervous system.” She pointed to Walter McConnell’s site-specific sculpture installed near the start of the exhibition as one expression. The contemporary artist’s memorial in the form of a stupa commemorates the thousands of pottery workers who died from lead poisoning.

Similarly, Microulis drew attention to a mural-size, Nineteenth Century visual of the Daisy Bank marl hole in Longton, Stoke-on-Trent. “I think the stark contrast between the smoke-wreathed pottery town and the colorful, shiny majolica on display makes a compelling statement on the inevitable tradeoff between the production of consumer goods and the social and environmental injuries that can result – certainly an issue of great relevance today.”

The traveling exhibition is augmented by an online version, a soft-cover publication titled Majolica Mania Highlights and a three-volume catalog. Designers have exploited the inherent strengths of each format. The catalog, approximately 1,000 pages in length and full of sumptuous color illustrations, is splendid and monumental. Ardent and meticulous scholarship, witty design and high production values are in clear view. (Full disclosure: I wrote one of the essays.)

During the Renaissance era, skilled artisans embellished rare natural-history specimens with mounts of precious materials. This object evokes a nautilus cup of the Sixteenth Century. Nautilus shell with lizard by Worcester Royal Porcelain Co., circa 1870. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 9¼ by 6-5/8 by 6 inches. Collection of Marilyn and Edward Flower. Photograph Bruce White.

But “Majolica Mania” is not simply an academic offering for passive consumption. Members of the research team encourage majolica admirers to get into the game themselves. Weber commented, “What’s fun about majolica is that you can still collect it today…. You can find pieces in flea markets, on eBay and all the sites, and begin to make your own small collection.” When asked if she had advice for collectors, Microulis answered, “eBay. There is something for everyone – and at all price points!”

Happy hunting.

In summary, “Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850-1915” is on view by timed reservation at the Bard Graduate Center, 18 West 86th Street, New York City, from September 24 through January 2. For information, 212-501-3023 or email gallery@bgc.bard.edu.

The exhibition travels to the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, from February 26 through July 31, 2022 and to the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, U.K., from October 15, 2022 through February 26, 2023.

The online exhibition is accessible via exhibitions.bgc.bard.edu/majolicamania.

The catalog was edited by Susan Weber, with Catherine Arbuthnott, Jo Briggs, Eleanor Hughes, Earl Martin and Laura Microulis. Bard Graduate Center and the Walters Art Museum published the catalog in association with Yale University Press.